One night during the Perseid meteor shower, Arianne thinks she sees a shooting star land in the fields surrounding her family’s horse farm. About a year later, one of their horses gives birth to a baby centaur.

The family has enough attention already as Arianne’s six-year-old brother was born with birth defects caused by an experimental drug—the last thing they need is more scrutiny. But their clients soon start growing suspicious. Just how long is it possible to keep a secret? And what will happen if the world finds out?

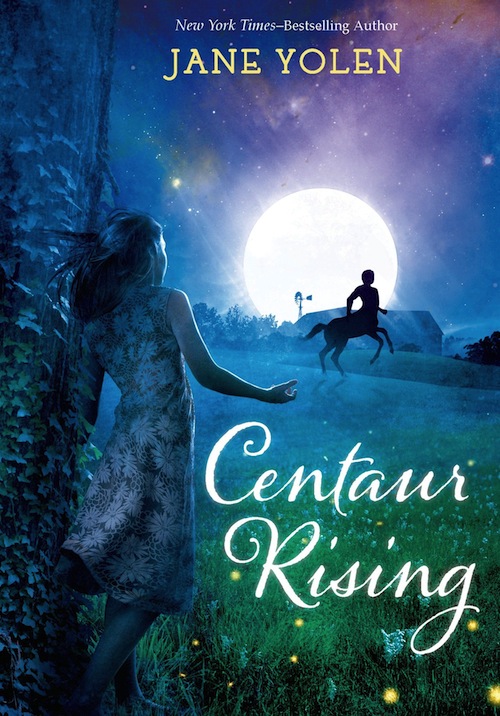

Jane Yolen imagines what it would be like if a creature from another world![]() came to ours in this thoughtfully written, imaginative novel, Centaur Rising—available October 21st from Henry Holt & Co.

came to ours in this thoughtfully written, imaginative novel, Centaur Rising—available October 21st from Henry Holt & Co.

August 1964

A Shower of Stars

In the middle of the night, Mom and I got out of bed, picked up Robbie from his room, put sweaters on over our pajamas, and grabbed a horse blanket from the barn. As soon as we were ready, we went out into the paddock to watch the Perseid meteor showers and count the shooting stars.

I spread out the blanket on the grass under a copse of maples so we blocked out any excess light but had a full view of the rest of the sky. Then the three of us lay down on our backs to watch.

There were occasional white sparks as stars shot across the sky. I clapped at the first one, and the second. Robbie did, too, in his own way. When the real fireworks began, we were all too awed to clap anymore. I just kept grinning, having an absolute gas.

Beside me, Robbie giggled and said, “See, Ari, like giant fireflies sailing across a bowl of milk.” He talks like that a lot, when he isn’t making up songs.

I’ve always been drawn to magic. Fairy tales, fantasy stories, worlds like Narnia and Middle Earth. Even before I could read on my own, Dad read them to me. He had this low, whispery, confiding voice that could suddenly boom out when the beast or troll or dragon appeared. No one else read me stories that way, like we were right there in the middle of the action.

I still had a musical jewelry box he’d given me after returning from one of his long tours with the band. It had a porcelain princess on top that turned around and around as “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” played. Mom made the princess wings out of pipe cleaners and lace so that she looked like a fairy. I called her Fairy Gwendoline. The song was tinkly and off-key, but it became my definition of magic. Or at least storybook magic, looking good and creaking along with a clockwork heart. As for real magic, I didn’t know any.

Maybe it all left with Dad.

Lying on the blanket, I thought about wishing on a star or on the Perseids. But they were just gigantic balls of light. High magic is not about science and star showers. I tore this quote out of a magazine and posted it above my mirror so I could read it every day: “Magic is about the unpredictable, the stunningly original, the not-containable or attainable. It can’t be guessed at or imitated or asked for. It happens and then it’s gone.”

And no, I wasn’t thinking about my dad.

At that point, our old pony Agora came over, looking at us as if puzzled that her humans were lying on the grass in the middle of the night. Easing to the ground on her arthritic knees, she snuggled up to us, whickering softly. Horses have a common magic, and they never let you down.

“She’s more puppy than pony,” Mom said, which made me laugh. It was good to laugh with her. That didn’t happen often anymore. I suddenly realized how much I missed it.

We were having a difficult time in our lives. That’s what Martha, our barn manager, called it. She was like a second mom to me. Six years before, when I was seven, and two weeks after Robbie had been born, Dad had left without an explanation. He’d never called or sent a letter afterwards. The bank mailed my mom a check from him every month that barely covered the farm’s mortgage. A really small check, considering what a famous rock star he is. Not Elvis famous. Not Bill Haley famous. Not Bobby Darin famous. But famous enough. We didn’t even know where he was most times, except when his band’s name appeared in the paper playing somewhere very far away, like San Diego or England.

I was still upset over his leaving, but Mom didn’t seem to be. Right after he left, she’d said, “He wasn’t actually here when he was here, you know,” which I hadn’t understood at the time.

After that, Mom and I never talked about much of anything except horses, my chores, and school. Since I could read on my own and got good grades, did my barn chores on time and without complaint, our conversations became fewer and fewer.

I didn’t have many friends. I first began to understand my lack of friends when earlier in the year some nutty guy on the news preached that the world was going to end before fall. Mom had laughed when she heard it, a sound as creaky and off-key as my old fairy princess box had been. “I thought six years of endings was enough,” she said, which was the closest she’d ever come to having the Dad Conversation with me. Besides, we didn’t believe in world’s end stuff. We were Quakers, which meant we believed that doing good, and peace work, in this life was important. We believed that each of us had God inside of us, and we had to listen to that still, small voice of love and reason, not some bearded guy in Heaven who was going to make the world end.

The kids in school talked about the prophecy, and some of them were scared. I thought it was silly to be scared of something like that and said out loud that only idiots believed such things. Jake Galla called me a Communist for saying that, which made no sense at all, and I told him so in front of our history class. A couple of the kids laughed, and Brain Brian even applauded.

I ignored Jake, having been called worse: Horse, Nitwit, and Ari-Fairy being the most common. It’s not exactly true that words can never harm you, but as long as you can learn to shrug them off, you can get along okay. I’d learned from the best— Martha.

Instead, I sometimes talked in front of the lockers with a few of the kids about our principal’s latest hair color, or what “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On” really meant. You’d never guess what Brain Brian thought it means! But talking to a few kids a few times in school didn’t translate into friendships. And besides, I had a lot of chores to do at the farm.

However, that August night, lying on the blanket with Robbie and Mom, looking at the star-streaked sky, it seemed the world was more like a light show than lights-out, more mechanics than magic, and even if I never got to share the Perseids with a best friend, I had Mom and Robbie and Agora, and I was okay with that.

Suddenly a huge star flashed right over the Suss farm next door, where the Morgan mares had been turned out into their field. I sat up, leaning on my left elbow as the mares startled, snorted wildly, and kicked up their heels.

Half awake, Robbie murmured, “Far out! And far away, too!”

At that exact moment, Agora got up a bit shakily, shook her head—which made her long mane dance about—and trotted over to the fence as if wanting to get closer to the show.

“Time for bed,” Mom said, standing. She grabbed up Robbie, balanced him on her hip, and headed for the house.

I didn’t complain. Chores start early on a farm, and I’m grumpy without at least a full eight hours of sleep. Even if it’s broken up. So, I just folded the blanket and started after them.

As we went through the paddock gate, I heard a strange whinny, like a waterfall of sound. Looking back, I saw something white and glowing sail over the fence between the Suss farm and ours, that high double fence that no horse—not even a champion jumper—can get across.

At first I thought it was a shooting star. Then I thought it was more likely ball lightning. And for a moment, I wondered if it might be the actual end of the world, in case we Quakers were wrong. Even as I had that thought and suspected I was dreaming, I took off after Mom and Robbie at a run, vowing to write about it in my journal in the morning.

July 1965

1

Agora’s Surprise

A mare is pregnant between 320 and 370 days, about a full year. Ponies give birth a bit earlier, more like eleven months. Mom taught me about that when we first came to the farm as renters, long before we bought out the old owner with the money she got from the divorce. When we moved here to Massachusetts, I was three, Mom and Dad were married, and Robbie wasn’t even a blip on the horizon, as Mom likes to say.

Mom grew up in Connecticut with horses and knows everything about them, even though her old farm, Long Riders, is long gone. As are my grandparents. A cul-de-sac of new houses sits on the old ménage and pasture, and the old farmhouse has become a gas station and general store. We drove past it once. It made Mom sad. Still, she knows horses inside and out, and what she doesn’t know, Martha does.

If Mom’s the owner of our farm, Martha McKean is its heart. Our riders call her “a regular horse whisperer,” and sometimes “the Queen”—except Mrs. Angotti, who once called Martha “Ivan the Terrible,” and the name stuck. Mom explained to me that Ivan was some Russian king nobody liked and who was really awful to everybody. Now everyone says it as a joke, and even Martha smiles at it.

Martha’s not awful at all, she just doesn’t like people much. Except she tolerates Mom and bosses Robbie and me around something fierce. Martha prefers horses, and it’s easy to guess why. The horses listen to her, and they do what she tells them to, almost as if she’s their lead mare. The rest of us listen when we want to, which isn’t often enough to please Martha.

So, near Thanksgiving last year, when Martha came into our house at dinnertime, a green rubber band in her hair, and said to Mom, “Old Aggie’s got something in her belly,” we listened, horrified.

Martha’s the only one to call Agora “Old Aggie.” I once asked her why, and she shrugged, saying, “Aggie told me to,” like it was no big deal that horses talked to her.

Mom’s hands went up to her mouth. She looked over at me, green eyes shining strangely, like a cat about to cry. Then the little pinch lines between her eyes showed up as she struggled to control herself, and I knew that there’d be no tears. There never are.

“Colitis?” I whispered to Martha.

It was the worst thing I could think of. If colitis hits a horse’s belly, it usually dies within hours, a day at most. We’ve never lost a horse to colitis, or anything else.

Martha warns us about once a month that losing a horse is bound to happen someday and we’d best be prepared. Times she talks like that, Mom calls her Aunty Dark Cloud.

Strangely, Martha laughed, a high whinnying sound. “Nah, not colitis. That old pony’s up and got herself pregnant.”

“Can’t have,” I said. “She’d need a stallion for—”

“Must be three months gone.” Martha’s hand described a small arc over her own belly.

Counting back on my fingers, I got to August, the month of the shooting stars.

Mom must have done the same counting. She said, “That darn Jove. I’ll call over and…”

Jove, the big Suss stud, had gotten out more times than we could count. It’s why we finally had to build the doublerowed fence between our fields and the Suss farm. We couldn’t really afford it, and Mom had called it “the most expensive birth deterrent ever,” but if we left it to Mr. Suss, it wasn’t going to happen.

Robbie laughed. “Aggie’s gonna have a baby!” he said. “Will it be bigger than her if Jove is the dad?”

Martha ignored him, shook her head, and said to Mom, “Old man Suss would have been over here yammering away at you had that rascal Jove got loose again. Suss would already be charging you a stud fee, like he’s done before. But he’s said nary a word, Miz Martins.” She never called Mom by her first name.

“Then how… ?”

It was the one question that troubled us the entire year of Agora’s pregnancy. But eventually I thought the two of them were looking in the wrong place for answers. I knew this was true magic in our lives at last, and the answer was in the sky.

I’ve never seen Martha out of uniform: those rumpled and stained blue jeans, a white or gray T-shirt in the summer and, in the winter, a dark-blue sweater with a hole in one sleeve. She wears sneakers in sun, rain, or snow, not like Mom who’s almost always in jodhpurs and boots with a well-ironed shirt during the day and a long Indian print dress in the evening after barn chores are done.

Martha’s gray hair is usually tied back in a ponytail with a fat colored rubber band, red when she’s feeling good, green when worried, blue when it’s best to leave her alone. Mom’s hair is pulled back in an ashy blond French braid when she rides, though at night it sits like a cloud on her shoulders. Is she beautiful? Dad used to say so. He called her the princess of ice and snow. He was dark to her light, heat to her ice. Or so Martha said once, and I never forgot it.

Sometimes I think Martha is probably part horse herself. And that’s what my English teacher calls a GOM, a good old-fashioned metaphor. Of course she’s truly human through and through, something I came to understand during the year after that night in the pasture when the stars fell all around us and a ball of lightning leaped over the fence.

Mom and Robbie and I live in the big farmhouse. It has fifteen rooms. “Far too many for just us,” Mom says whenever we have an all-family cleaning day. We can’t afford help, except for Martha, who only does the barn work. So Mom and I do the mopping and dusting while Robbie in his wheelchair is piled high with cleaning stuff that he hands out as we make our way around the house.

Maybe the house is too big for us, though I remember when Dad was here, how he seemed to fill the place up with all his stuff. In those days, we had a guitar room, a pool table room, plus a band room attached to two recording rooms that Dad called The Studio. And then there were bedrooms for all his band mates and roadies to stay over in as well. These days we just have empty rooms and loads of doors in the hallway that we keep closed year-round.

The old band room on the first floor is now Robbie’s bedroom, with its specially made shower that a friend of Mom’s built in one of the old recording rooms, trading his work so that his kids could have a year of free riding.

When Robbie was born, Dad left and took with him all the people who’d moved in—including the special nurse who was supposed to help care for Robbie but instead became a special backup singer in his band. We never got another nurse, because Mom just didn’t have the money for one. She moved her bed into the old pool table room so she could be right next door to Robbie. That left me with the entire upstairs. So I have a playroom and a music room and a room for my riding trophies. And there’s two extra rooms for friends, if I ever have any friends who want to stay over.

We even have room for Martha to live with us, but she has a one-bedroom cottage on the other side of our driveway. She’d been living there when we arrived, and she likes her privacy. In fact, she likes it so much, I’ve never been invited inside. But I bet it has horse pictures on the walls.

Agora’s pregnancy seemed routine, which was good. Because of her arthritis and her age, we’d always figured giving birth would be too hard on her, so we’d never had her bred. But then she accidentally bred herself.

Nevertheless, we were all really concerned. Agora had been a rescue pony whose last owner had nearly starved her to death. Martha said the owner should have been put in jail for life! I’m sure she was just making a joke. Well, almost sure.

Dr. Herks, the vet, checked her out once a month during her pregnancy, until the last two months, and then he came to see her every other week. Martha grumbled that he was around the farm so much, he was like a puppy underfoot.

Mom just laughed at Martha. “It’s nice to have a vet so dedicated to his work,” she said. “And since this is Agora’s first foal…”

“And last,” Martha reminded us.

The day everything changed on the farm was the day Agora went into labor. It was Saturday morning, and I was doing the usual barn chores, mucking out stalls, putting in fresh straw, filling water buckets. I’d just finished the stalls of the old men, as we called our aging geldings.

Robbie was with me, sitting in his wheelchair, telling me bad six-year-old jokes. I mean the jokes six-year-olds tell, not that the jokes were six years old. He gets them from books and from our small black-and-white television set. I didn’t have time to watch much TV, what with my homework and barn chores, so Robbie used to catch me up on everything he’d seen—mainly Bewitched, Flipper, The Munsters, Daniel Boone, Mister Ed, and The Addams Family. He would have watched all day if Mom had let him. And he could go on and on about the shows to anyone who’d listen. Half the time, I didn’t pay any attention, just nodded and did my homework or my chores. I didn’t let him know I wasn’t completely involved in every plot turn and joke, or he’d never stop explaining.

Martha talked that way, too, on and on, with me tuning out. All she did was tell me how to do what I’d been doing for the past four years, since I was nine. Calling me “Little Bit” and “Shortie,” even though I was neither of those anymore. Calling Robbie “Squinch” (because of his glasses) and “Munchkin” (because he’s so small).

Martha wanted things done right, meaning her way, so how could I be mad at her? Annoyed a little, irritated some, but not mad. Martha was an itch we all had to scratch.

And Robbie? He just called her silly names back: “Marmar” when he was little, “Mairzy Doats” from a song Martha used to sing, and now “Marmalade” from his favorite jam, which is so bitter, I won’t eat it. “More for me,” he always says.

I rolled Robbie to Agora’s stall next, and we could hear rough breathing. When I peeked in, Agora was standing with her head hanging down, and she didn’t look good.

“Keep an eye on her, buddy,” I said to Robbie, “I’ve got to call the vet.”

“Will she be okay?” I could hear the tightness in his voice.

“Dr. Herks is the best,” I reminded him. “Try and keep her calm.”

He nodded. “I’ll sing to her.” He loved singing to the horses. He had a great voice, always right on key. Not like me. Mom says it’s the one good thing he got from Dad.

I left Robbie at the open door, not that there was much he could do if things went wrong. He can’t use his legs, his pelvic bones are missing, his arms are too short, and his hands are like flippers because the fingers and thumbs grew fused together.

But that voice… Martha calls it angelic, only not to his face. He was already singing to Agora, to keep her calm. “A horse is a horse, of course, of course.…” It was the theme song from Mister Ed.

I’d seen mares in labor before. Their tails twitch high, and sometimes they stomp about the stall as if they can’t quite settle. Then, suddenly, they collapse on the ground, rolling over on one side, the water flooding out of their hind ends. Several long pushes later, a white sac like a balloon comes out with one or two tiny horse hooves showing.

The first time I watched a mare have a baby, I thought it was disgusting. Yet once the foal stood up, shaking all over and then walking about on its spindly legs, everything was so magical, I forgot about the icky stuff.

But what I was hearing that day from Agora’s stall didn’t sound like magic. It sounded like pain. I couldn’t take time to comfort her. Robbie would have to do that. He was good with the horses since, unlike most kids his age, he didn’t make quick movements or too much noise.

I ran to the barn phone.

The vet’s number was written on the wall over the phone in black paint. As Martha said, “Pieces of paper can get torn off or lost, but black paint is forever.”

He answered on the first ring, his voice low, musical. “Gerry Herks here.” He always sounded like a movie star, though he didn’t actually look like one. Just pleasant-faced with brown eyes and graying hair.

“Arianne Martins here.”

“Everything all right at the farm?”

“It’s Agora. It’s…”

“It’s time,” he said brightly. “I’ll be right there.”

Centaur Rising © Jane Yolen, 2014