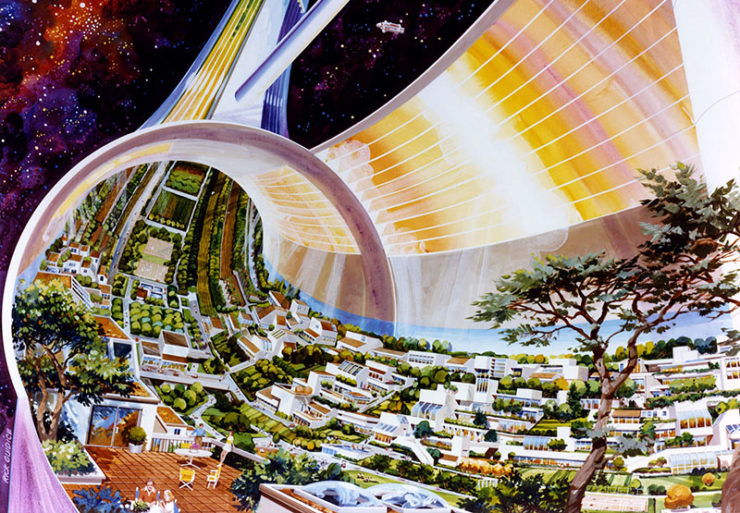

In 1974, Gerard K. O’Neill’s paper “The Colonization of Space” kicked off what ultimately proved to be a short-lived fad for imagining space habitats. None were ever built, but the imagined habitats are interesting as techno dreams that, like our ordinary dreams, express the anxieties of their time .

They were inspired by fears of resource shortages (as predicted by the Club of Rome), a population bomb, and the energy crisis of the early 1970s. They were thought to be practical because the American space program, and the space shuttle, would surely provide reliable, cheap access to space. O’Neill proposed that we could avert soaring gas prices, famines, and perhaps even widespread economic collapse by building cities in space. Other visionaries had proposed settling planets; O’Neill believed it would be easier to live in space habitats and exploit the resources of minor bodies like the Earth’s Moon and the asteroids.

Interest in O’Neill’s ideas waned when oil prices collapsed and the shuttle was revealed to have explosive flaws. However, the fad for habitats lasted long enough to inspire a fair number of novels featuring O’Neill-style habitats. Here are some of my favourites.

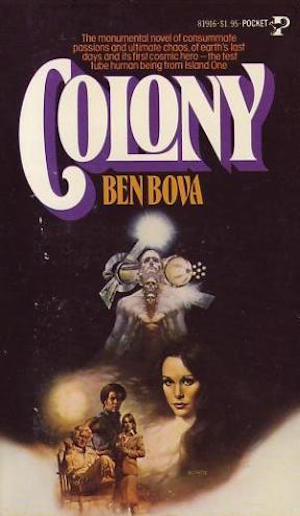

Ben Bova’s 1978 Colony is set eight years after Bova’s Millennium. The world is unified under a World Government, but the issues that nearly drove the Soviet Union and the United States to war in late 1999 persist. Only a single habitat has been built—Island One, orbiting at the Earth-Moon L4 point —and it will not be enough to stave off doomsday. This suits the billionaires who paid for Island One just fine. Their plan is to provoke doomsday, wait it out in Island One, then rebuilt Earth to suit their discerning tastes.

Colony is not without its flaws, chief among them a sexism impressive even for the era in which it was written; Bahjat, one of the few women with agency in the book, is essentially given to protagonist David as a prize at the end of the novel. Still, there’s one element in the setting that endeared the book to me; there is no refuge for malevolent oligarchs that the labouring classes cannot reach … and destroy. All too many SF novels have sided with the oligarchs (let the canaille die!). A book that took the side of the teeming masses was a refreshing change.

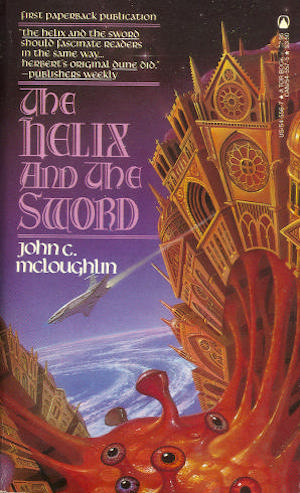

As far as I know, John C. McLoughlin only published two novels: The Toolmaker’s Koan (which wrestled with the Fermi Paradox or rather the Great Filter) and his space-habitat book, The Helix and the Sword. Set five millennia after resource shortages, pollution and war have ended the European Ascendancy, an asteroid-based culture finds itself on the brink of a Malthusian crisis like the one that doomed Earth five thousand years earlier.

Malthusian crises, a devastated Earth, and space based civilizations were common features in 1970s and 1980s SF. What makes The Helix and the Sword interesting is its imagined biotechnology, which allows the space-faring humans to grow ships and habitats just as we might grow crops or domestic animals. It’s a pity that the political institutions of the world five thousand years from now have not kept pace with the biotech.

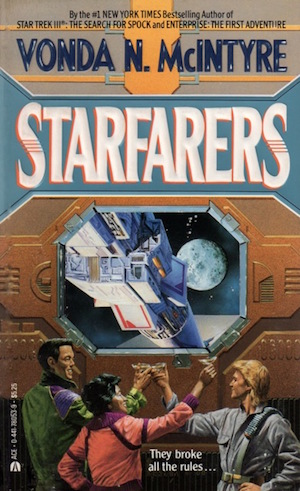

The eponymous Starfarers of Vonda N. McIntyre’s Starfarer Quartet is a habitat (well, a pair of habitats that function as one craft) that is small as space colonies go. But it’s agile and fast: it sports a vast light sail and has access to a handy cosmic string that can take it to the stars. The US government sees it as a potential military resource; the inhabitants hijack it rather than be conscripted. However, they are not prepared for what they find at Tau Ceti.

It’s best not to calculate how many square kilometers of light sail even a small craft would need for even a small acceleration , let alone the accelerations Starfarer seems to enjoy.

Starfarer was imagined in a series of panels at Portland’s Orycon convention. It’s interesting as a setting that explores more than tech. McIntyre is interested in relationships other than the male-female pairs assumed by most SF authors.

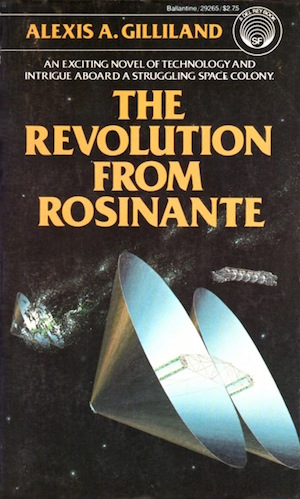

Set a generation after the welding of Canada, Mexico, the United States, and other nations into a fragile North American Union, Alexis Gilliland’s The Rosinante Trilogy chronicles the end of a golden age, as the space habitat investment bubble suddenly bursts. It features a heavy-handed government, determined to crush dissent even where it does not exist, and engineers who build without asking what the consequences of their inventions might be.

Gilliland’s cheerfully cynical tale is one of very few stories to play with the idea that space habitats might prove as solid an investment as tulips and bitcoins. That alone would have made it memorable. The books are often quite funny. I still relish the memory of the artificial intelligence Skaskash, which invented a religion that was way more successful than it expected.

THERE IS NO GOD BUT GOD AND SKASKASH IS ITS PROPHET!

No doubt those of you of a certain age have your own favourites. Feel free to mention them in comments.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nomineeJames Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is surprisingly flammable.