Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

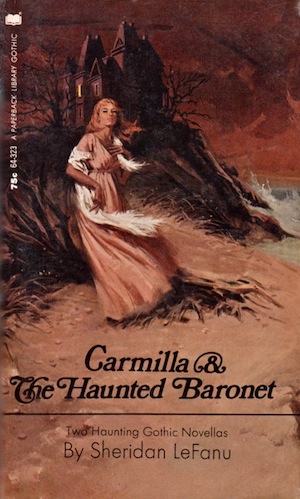

This week, we continue with J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla, first published as a serial in The Dark Blue from 1871 to 1872, with Chapters 7-8. Spoilers ahead!

The day after her dream of the pacing panther, Laura can’t bear to be alone. She feels she should tell her father but refrains, fearing he will either laugh at her or be far too alarmed. She does confide in Madame Perrodon, who looks anxious, and Mademoiselle Lafontaine, who laughs and remarks that a servant has seen a female ghost walking at dawn in their lime avenue. Mademoiselle mustn’t mention the ghost story to Carmilla, though, for Carmilla can see the avenue from her window and will be terrified.

Coming downstairs later than usual, Carmilla relates a nocturnal experience similar to Laura’s. She dreamed something black was circling her bed; starting awake, she thought she saw a dark figure by the fireplace, but it vanished as soon as she touched the hunchback peddler’s charm she’s been keeping under her pillow. Laura decides to pin her own charm to her pillow that night. For two nights her sleep is deep and dreamless, though she wakes with a sense of almost-luxurious lassitude and melancholy. Carmilla believes that dreams like their result from fevers or other maladies that, unable to enter one’s body, pass by with merely an “alarm.” As to why the charm works, it’s clearly been fumigated with some drug to hold off “the malaria.” Evil spirits, she scoffs, aren’t afraid of charms, but wandering complaints can be defeated by the druggist.

Laura sleeps well for some nights more, but her morning languor begins to linger all day. Her strangely pleasant melancholy brings “dim thoughts of death” and a not unwelcome idea that she’s slowly sinking. Whatever her mental state may be, her “soul acquiesced.” Meanwhile Carmilla’s romantic episodes grow more frequent as Laura’s strength wanes.

Unknowingly, Laura reaches “a pretty advanced stage of the strangest ailment under which mortal ever suffered.” Vague sensations of moving against the cold current of a river invade her sleep, along with interminable dreams the details of which she can’t recall. Her general impression is of being in a dark place speaking to people she can’t see. One deep female voice inspires fear. A hand may caress her cheek and neck. Warm lips kiss her, settling on her throat with a sense of strangulation and a “dreadful convulsion” that renders her unconscious. Three weeks pass, and her sufferings begin to manifest physically in pallor, dilated pupils, and circles under her eyes. Her father often asks if she’s ill; Laura continues to deny it. And, indeed, she has no pain or other “bodily derangement.” Her illness seems “one of the imagination, or the nerves.” It can’t in any case be the plague peasants call “the oupire,” whose victims succumb within three days.

Carmilla complains of dreams and “feverish sensations” less severe than Laura’s. The “narcotic of an unsuspected influence” benumbs Laura’s perceptions; otherwise she’d pray for aid!

One night the usual voice of her dreams is replaced by a tender yet terrible one that says, “Your mother warns you to beware of the assassin.” Light springs up to reveal Carmilla standing at the foot of Laura’s bed, her nightdress soaked from chin to foot with blood. Laura wakes shrieking, convinced Carmilla’s being murdered. She summons Madame and Mademoiselle. All three pound on Carmilla’s door, receiving no response. Panicked, they call servants to force the lock. They find the room undisturbed. But Carmilla is gone!

The women search Carmilla’s room. How could she have left it when both the door to the hallway and the dressing room door were locked from inside? Could she have found one of the secret passages rumored to exist in the castle? Morning comes, Carmilla still missing, and the whole household scours house and grounds. Laura’s father dreads having a fatal tale to tell Carmilla’s mother. Laura’s grief is “quite of a different kind.” Then, at Carmilla’s usual afternoon waking time, Laura finds her guest back in her room and embraces her in “an ecstasy of joy.” The rest of the household arrives to hear Carmilla’s explanation.

Buy the Book

And Then I Woke Up

It was a night of wonders, Carmilla says. She went to sleep with her doors locked, slept soundly without dreams, then woke in her dressing room, the door of which was open, while her hallway door had been forced. How could she, so light a sleeper, have been moved without waking?

As her father paces, thinking, Laura sees Carmilla give him “a sly, dark glance.” Then her father sits beside Carmilla and offers his solution to the mystery. Has Carmilla ever sleepwalked? Only as a young child, Carmilla says. Well, then. She must have sleepwalked last night, opening her door and carrying off the key. She must then have wandered into one of the castle’s very many rooms or closets. Then, when everyone had gone back to bed, Carmilla must have sleepwalked back to her room and let herself into the dressing room. No burglars or witches need be brought into the story—the explanation is “most natural.”

Carmilla is relieved. She is, by the way, “looking charmingly,” her beauty only enhanced by her peculiar “graceful languor.” Laura’s father apparently contrasts Carmilla’s looks with Laura’s, for he sighs that he wishes his daughter were looking more like herself.

Nevertheless, the household’s alarms are now happily over, for Carmilla is “restored to her friends.”

This Week’s Metrics

By These Signs Shall You Know Her: Carmilla’s whole feeding process has a complex symptomology, starting with the initial fearful bite, descending into pleasurable melancholy and fascination, which increases until it suddenly tips over the edge into a “sense of the horrible” that “discolored and perverted the whole state of my life.” There are awful nightmares, leaving her victim with a sense of strange conversations and great mental effort and danger.

What’s Cyclopean: Carmilla lavishes Laura with “strange paroxysms of languid adoration…”

Madness Takes Its Toll: …which shock Laura “like a momentary glare of insanity.”

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Carmilla does not have the idiot ball this week. She continues her excellent trick of forestalling suspicion by sharing all of Laura’s unpleasant experiences and bringing them up before Laura does. She had a terrible dream! An animal leapt on her bed! And then she touched the amulet and it went away! Clearly she and Laura are destined to be soulmates, for they share so many experiences. Laura will die, sweetly die—ahem.

When she’s not coming on like Lord Byron housebound by an inconvenient storm, Carmilla also has a rational explanation for everything. The amulets aren’t magic, of course, but soaked in some sort of medicine that wards off fever. These terrifying experiences are merely the brush of that fever before the medicine kicks in.

Next time I bump into a self-proclaimed “skeptic” at a party, I’m going to point out that they’re obviously trying to cover for being a vampire.

Trick #3 has to be Laura’s dad’s own illness. He’s become “rather an invalid,” which I’m sure is a complete coincidence. So apparently Carmilla can not only kill faster than she does with Laura, but slower. I also spoke too soon about the lack of pleasure in her bite. While the initial stab is painful and scary, over the long term her feeding leads to a pleasurable decline, “a sense of lassitude and melancholy, which, however, did not exceed a degree that was almost luxurious,” which I’m sure is not at all by analogy to opium addition. Or maybe vampires turn you into a romantic poet, welcoming the sad-yet-sweet idea of death, which is not very surprising given the origins of the modern genre. (Sorry, I seem to have Byron on the brain this week for some reason.)

Beyond these emotional effects, there’s also the “unsuspected influence that keeps Laura from reporting her problems to her father, who might recognize them from that letter he received at the beginning of the this whole business. Or at least worry enough to call in a doctor, maybe even the one who sent said letter and would certainly recognize the problem (as well as recognizing Carmilla herself).

Even when Carmilla’s caught out by an unexpectedly wakeful Laura, she makes the best of it. Maybe she has, in fact, discovered the schloss’s secret passageways, or just remembers them from earlier in her life—a convenient way to get around locked doors! In the end, her dramatic disappearance and reappearance attract attention to her, and away from Laura’s own suffering. And it ultimately provides yet another opportunity for rational explanation of strange events.

I love the general idea of lesbian vampires—and there are many excellent ones to choose from—but have to admit that the deeper we get into Carmilla the less appealing she personally becomes to me. Last week it was stalkery drunk texts. This week she reminds me all too creepily of the people who slowly poison family members so they can properly demonstrate their devotion via caretaking (and so said relatives have no choice but to acquiesce to their suffocating care).

This is not a promising direction for any sort of relationship Laura could actually enjoy.

Anne’s Commentary

Annabelle Williams has written an intriguing article about our current read, “Carmilla is Better Than Dracula, and Here’s Why.” She points out that while Le Fanu’s novella precedes Stoker’s Dracula by 25 years, it’s the Count rather than the Countess who’s become pop culture’s “default vampire.” And yet, “the tropes we associate with 21st-century vampire fictions—linking sex and the forbidden, romantic obsession, and physical beauty—map onto Carmilla more than Dracula himself.” I agree that text-Carmilla outshines text-Dracula in sex appeal, as within Dracula itself do the Count’s three brides. Film loves those brides, who are so eager to press their “kisses” on the prim but not-quite-unwilling Jonathan Harker. Particularly hot, in my opinion, are the very well-dressed and -coiffed ladies of the 1977 BBC production. But then you wouldn’t expect that production’s king-vampire Louis Jourdan to keep his ladies in tattered shrouds.

Speaking of attire. Laura must be supplying Carmilla out of her own wardrobe, since her guest arrives with nothing but the outfit on her back and a silk dressing gown her “mama” throws over her feet before leaving for parts unknown. What, a beauty like Carmilla doesn’t travel with at least one overstuffed trunk? Or does traveling so light intentionally emphasize the emergency nature of “mama’s” business? Dressing in her intended victim’s clothes may also gratify some kink of Carmilla’s and buoy the critically popular idea that Carmilla and Laura represent the dark and light sides of the same person.

Maybe Le Fanu didn’t deeply ponder the clothing situation or the heavy-duty spotlifters Carmilla would need to get bloodstains out of her finery. That stain from neckline to hem of her nightdress must have been a bitch to remove! I concede that this carnage might just have been part of Laura’s fevered dream, whereas Carmilla was actually a fastidious diner, which would also explain why no telltale bloodstains ever besmirch Laura’s nightdress or bed-linens. Blood on one’s pillowcase was scarily diagnostic of consumption during the 19th-century. Consumption and vampirism also shared the symptoms of pallor, sunken eyes, general weakness and—wait for it—languor. Fang-tracks would render differential diagnosis simple, but in “Carmilla,” these dead-giveaways are cryptic.

Oh well. Few vampire epics tackle the messiness factor as directly as What We Do in the Shadows, in which the neat-freak vampire mistakenly taps an artery, causing blood to geyser all over his antique couch. You gotta hate it when that happens, I don’t care how undead you are.

Of particular psychological interest is how Carmilla continues to deflect suspicion by claiming to share Laura’s weird experiences. The strategy’s rendered more effective because she always beats Laura to the punch rather than echoing Laura’s stories, a feat possible because Carmilla has been or will be the perpetrator of every wonder or horror. While Laura stands dumbstruck at seeing in her guest the face of her childhood dream, Carmilla exclaims that she saw Laura’s face in a childhood dream! After the pacing panther incident, Carmilla blurts out her own nightmare of a restless black beast and menacing human figure. After a maternal ghost interrupts Carmilla’s feast, she takes advantage of how Laura misinterprets its warning—Carmilla is not the wounding assassin but the assassin’s target! To reinforce Laura’s dread for rather than of herself, Carmilla vanishes overnight, then returns as confounded by the locked-door mystery as Laura. A little slip: Laura catches the “sly, dark glance” at her father that suggests Carmilla counts on him to explain away the inexplicable to everyone’s satisfaction. Carmilla may well look “charmingly” after Papa supplies her with “the most natural explanation” for her disappearance: sleepwalking.

By “sharing” Laura’s experiences, Carmilla also increases Laura’s sympathy for her. How alike they are, destined after all to be close friends.

Friends with benefits, in fact. Carmilla gets the lioness’s share of those perks, but not all of them. Laura’s participation being unknowing and therefore nonconsensual, she’s absolved from guilt when she takes pleasure in their nocturnal connection. The eroticism is either explicit, as in the intensity of Carmilla’s kisses, or strongly implied, as in Laura’s reaction:

“My heart beat faster, my breathing rose and fell rapidly… a sobbing, that rose from a sense of strangulation, supervened, and turned into a dreadful convulsion, in which my senses left me and I became unconscious.”

That sounds like quite the orgasm and some hardcore erotic asphyxiation, too. No wonder that when Laura slips from the pleasurably languorous phase of her ailment, she feels “it discolored and perverted the whole state of my life.” She must insist she’s the entranced victim and not the co-perpetrator of forbidden sex, or she can’t justify her long silence—or her Victorian audience’s titillation. Carmilla must be no mere human seductress but an undead bloodsucker. Vampires are THE perfect monster for wholesome erotic horror. You can’t blame the objects of their loathsome affection for submitting, for vampires have often had centuries to hone their manipulative powers. Even young vamps have Dark Powers on their side, and so the sexy morality play can only end with the victory of the Light and the rescue of the innocent by…

By whom? Upcoming chapters must tell.

Next week, we meet a more commercial sort of vampire, in Fritz Leiber’s “The Girl With the Hungry Eyes.” You can find it in innumerable anthologies, including Ellen Datlow’s 2019 Blood Is Not Enough collection.

Ruthanna Emrys’s A Half-Built Garden comes out in July 2022. She is also the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.