Illustrator John R. Neill had been part of the creation of Oz almost from the beginning. (The very first Oz book had been illustrated by William Wallace Denslow, thus accounting for its very different look.) It’s probably safe to say that Neill’s marvelous illustrations had a significant, positive effect on the popularity of the series. The lavish, striking images gave Oz a recognizable look, helped shore up the weakest of the Baum books, and provided visual continuity for readers when Ruth Plumly Thompson took over the series, helping readers adjust to the inevitable change in tone, focus and ideas. Neill’s image of the Scarecrow, for instance, is the Scarecrow (with all due respect to Ray Bolger’s singing and dancing version), no matter who might be penning the dialogue. And, after reading and illustrating 32 Oz books, Neill could rightfully be regarded as one of the genuine living experts on Oz.

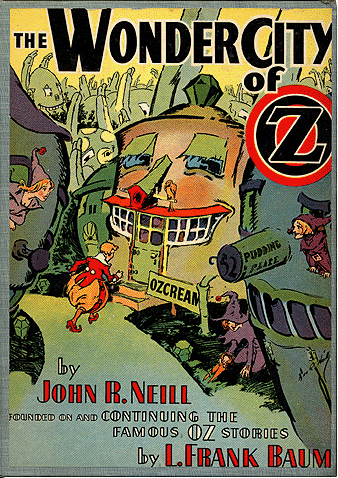

Not surprisingly, therefore, Oz publishers Reilly and Lee, failing to persuade Ruth Plumly Thompson to return for another Oz book, turned to John R. Neill to continue the series. The result, however, The Wonder City of Oz, was probably not what they, or anyone, expected.

Including Neill.

The Wonder City of Oz begins in New Jersey, where a girl called Jenny Jump turns into a bad tempered half-fairy after meeting a leprechaun. I would not have thought that New Jersey was a favorite stomping ground for leprechauns, but whatever. After this, things stop making sense.

Let me explain. No, it’s too complicated. Let me sum up.

Jenny jumps into Oz and there’s a party and then she decides to tell Ozma about elections and Ozma decides to have one and Jenny runs against her but first she opens up a style shop where she hires a kid called Number Nine and kinda tortures him into working by putting him into screaming pants and then the houses who mostly like Ozma start fighting with Jenny’s house and throwing around lightning rods and bits of their roofs at one another and Jenny gets mad again and then she tries to buy off the Ozelection only it doesn’t work because she’s accidentally collected the wrong shoes and then she gets into an Ozoplane with Jack Pumpkinhead and Scraps and they crash on Chocolate Land (or something) and in the least believable scene in the entire book start fighting with chocolate and there’s some gnomes looking for warts (it’s best not to ask) and a cute little two headed purple dragon and Sir Hokus and some cats and some shallow reflections on how anyone can win an election when trapped in a chocolate jail and then a fight between chocolate and singing shoes and Kabumpo and a voice that lost its body and zip zip around Oz by Sawhorseback and then Jenny takes over the defenses of the Emerald City (no, of course Ozma’s not involved in defending the city. I told you, Neill read the books and was an expert on Oz) and the Wizard of Oz melts a chocolate jail on a chocolate star and Scraps and Jack Pumpkinhead slide into Oz and there’s another Ozelection which has to be fixed to prevent a landslide since the country is too fragile to survive a landslide ha ha ha and the leprechaun reappears and there’s some bulls and another dragon and Jenny gets a lobotomy and becomes a Duchess The End. Oh, and Scraps hits a lot of people.

I understate. Deeply understate.

Even long term, devoted Oz fans can be forgiven for not being able to follow this book or understand much of what’s going on: incoherent is an understatement.

This was not the result of deliberate authorial or editorial choice: rather, the book, although credited to Neill, was the product of two different authors: one of whom, alas, did not know how to write (Neill) and the other one of whom, more alas, did know much about the book. The second writer, an anonymous editor at Reilly and Lee, was apparently responsible for bits like the nonsensical Ozelection. Seriously nonsensical: the first vote is based on…shoes, on the basis that people have too many umbrellas for voting purposes. (I’m not making this up. Seriously. This is the argument for the shoes.) In more gifted hands, this scene could have shone with the lunacy of a Lewis Carroll. These are not gifted hands.

This dual authorship also helps explain at least some of the book’s many internal inconsistencies, which are almost too many to count. The distinct impression is that the editor assigned to rewrite and add to the book either did not read, or did not understand, Neill’s sections. As a result, the main character, Jenny Jump, swings between cautious and impetuous, kindly and bad tempered, intelligent and unthinking—often on the same page. She also grows progressively younger, possibly because of the leprechaun, or possibly not, and why precisely she, alone of any visitor to Oz, needs a lobotomy is really not clear. (I’m also not sure why Ozma is encouraging this sort of thing.)

It’s not just Jenny, either. For example, on page 234, Jenny informs Number Nine that Scraps and Jack Pumpkinhead are imprisoned in chocolate and in dire need of rescue (look, the book doesn’t make much sense). An unconcerned, untroubled Number Nine suggests working in the store and celebrating. By page 236, Number Nine is suddenly freaking out that he might be too late to rescue Scraps and Jack Pumpkinhead. Similar examples abound.

Behind all of this are some possibly intriguing ideas that never really do get worked out. In a way, for instance, Jenny can be seen as attempting to introduce—or reintroduce—American political concepts to an Oz that had been a communist utopia under Baum, and a wealthy aristocracy with generally satisfied (and mostly unseen) peasants under Thompson. But to say that these attempts misfire is to put it kindly. The Ozelection that Jenny initiates is eventually decided in the most arbitrary of ways: the Wooglebug determines how much an individual vote should count by literally weighing people, comparing the weights of people who vote for Ozma with those who vote for Jenny. In further proof that I’m not the only one to express doubts about the leadership abilities of the Girl Ruler, the final vote comes out almost exactly even—how desperate must the Ozites be to vote for an often bad tempered clothes stylist who likes to fight with chocolate instead?

I also have no idea why Ozma, either in her role as the royal daughter of Pastoria, last in a long line of fairy kings, or as the fairy entrusted with the rule of Oz by Lurline, or as the inexplicably beloved ruler of the fairyland, would agree to have the election in the first place. After a first, horrified response, Ozma has always, but always, known herself to be the Ruler of Oz and accepted her responsibilities, even if she has failed to carry out about half of them. If the election had been sparked by a serious discussion of exactly why Ozma still doesn’t have a security system or any way to stop the multiple invasions of Oz, however great her follow-up parties, I might have accepted it, but for Ozma to just nod and say, hmm, sure, on the suggestion of a complete stranger from New Jersey is just too far fetched to believe, even in Oz. And any idea of handing over the country to a complete stranger makes no sense in a series that continually focused, even in Baum’s days, on ensuring that the correct, authorized rulers remain in place, no matter who they might be.

Jenny’s other attempts to add two more American values—hard work and punctuality—to Oz do not go too well either. She literally has to torture Number Nine into hard work. (He finds this torture entrancing. I’m not sure we’re ready to explore the implications of this from an Oz perspective.) The clocks start lying to her and eventually run away. (I must admit I can see the appeal of a clock like this.)

But the fundamental problem with this book is that much of it is simply terribly written. Neill cannot be faulted for a lack of imagination—if anything, the book is rather too imaginative—but he had not learned how to turn these ideas into written words. The book’s sentences are frequently so choppy that they can be difficult to read. The mess also stems from a serious misunderstanding about Oz: Oz is fantastical, filled with puns and strange and odd creatures, but not nonsensical. Someone—either Neill or the editor if not both—attempted to turn Oz into nonsense here, and decidedly failed.

With this said, I did enjoy parts of the book: the little dragon, the cats on leashes, and the return of Aunt Em and Uncle Henry, and if I can’t envision ever fighting with chocolate myself (I would surrender immediately, as far too many people can gleefully testify) the illustrations were highly entertaining. Then again, when I read it, I was high on scones, coffee, and Lost frustration—the last of which greatly increased my tolerance for improbable events and dropped plot lines.

Neill did not find out that his manuscript had been severely altered until it arrived in printed form on his doorstep. The severe editing and rewriting of this first novel failed to daunt him: he sat down to pen his next masterwork: the infamous (in Oz circles) Scalawagons of Oz.

Mari Ness finds that the thought of fighting with chocolate makes her terrified and faintly ill. She lives in central Florida.

Wow. On the plus side, the cover illustration is entertainingly disturbing. A house with a hey-hey-hey expression and a sign out front reading OZCREAM is–well, I don’t really know. Also, weirdly, I like the Deco font.

But I think I’m fine with stopping at the cover.

I, too, am against fighting with Chocolate. To what avail? Chocolate will always win. I suppose it is a good thing Chocolate did not chose to invade Oz or else Ozma would be usurped by Chocolate. Or maybe become Chocolate.

A Chocolate Ozma. hmmmm. That might just make everything better.

The plot sounds an awful lot like how my son used to relate his dreams to me back when he was four or five, before he discovered Star Wars. I miss those days, and those dreams. They didn’t make any sense at all, but they were terribly sweet. :)

I once did a casual comparison of the published Wonder City of Oz with the manuscript–I believe it was when I was working on The Runaway in Oz. You have to read to at least chapter six of the published book before you reach a sentence that JRN actually wrote.

Not that JRN’s original manuscript is any great shakes. It displays all the reason that the editors at Reilly & Lee thought it needed an overhaul. However, I’m not sure it needed THIS overhaul.

The Wonder City of Oz seems to me like a parody of an Oz book. The first time I read it I really enjoyed it for all its preposterousness, each incident more laughably outrageous than the last. I liked it better for those reasons than the other two JRN Oz books. They’re actually his prose, but the stories are less over-the-top than this one.

Hi everyone! Delayed responses since I sprained a finger right when under a deadline for a completely unrelated (and much less fun) project. Anyway!

@seth e The illustrations are really marvelous – Neill completely lets himself go. The problem is the surrounding prose. It might be fun to create a book just of Neill’s illustrations, including the ones for this book – to let everyone enjoy the images without getting tortured by the prose.

@Longtimefan – Oooh! Chocolate Ozmas! I could work with that.

@zenspinner – Wonder City does have a definite dreamlike quality to it.

@eric Shanower – Interesting. Those first six chapters contained some of the worst and most choppy writing, too.

I thought Lucky Bucky was by far the best of the three Neill books, although I’m not sure that’s saying much. Maybe I just liked the whale and the pies. I do agree that Wonder City is a more enjoyable read than Scalawagons where people mostly seem to be driven around by the little cars, but I didn’t find it an easy read, either, mostly because parts of the prose were just so awful, and because the internal contradictions got to be too much. Maybe if I’d thought of it as an Oz dream sequence, it might have gone better.

I disagree. W. W. Denslow drew the definitive versions of the Oz characters in the (sadly) only Oz book he illustrated, “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz”. Which is why MGM used his versions, as opposed to Neill’s. When you compare the two artists, you can see the superior design sense, and personality, and craft in Denslow’s work. It’s especially apparent in Denslow’s depiction of the Tin Man, as opposed to Neill’s. Denslow’s Tin Man has a charm (not to mention a round head) that Neill’s completely lacks. Indeed, my enjoyment of the later Oz books was compromised when I saw their illustrations. Such a letdown after Denslow’s. The only Neill book I like is The Land of Oz, in which, interestingly, he strove to mimic Denslow. All the other books look like they were drawn by the Gibson Girl artist. And as a kid I found the art boooorriinggg.

@Charmbear – I like Denslow’s illustrations – they’re charming, and he did draw the cutest versions of Toto, bar none. But I don’t like Denslow’s Dorothy, and…I’m trying to think how to phrase this…the other illustrations are almost too childlike for me, and not quite magical enough. And I’m not sure you’re giving Neill enough credit for his magical landscapes and creatures, where he gives a distinct sense of fairyland, something I loved as a kid and still like now. (Plus, if you look closely, several illustrations have little jokes or fine details which add to the fun.) And if I recall correctly, Neill only mimicked Denslow once, in that illustration in Road to Oz where Dorothy encounters her tin statue. I took it less as an attempt to mimic Denslow and more as a graceful acknowledgement/complement.

Although you certainly have a point with the Gibson Girl quality of many of Neill’s women!

But I don’t think MGM was making any sort of artistic judgement when they used Denslow’s versions instead of Neill’s. They used Denslow’s versions because they had unquestioned film rights to the entire book, including the illustrations, and were well aware that Ruth Plumly Thompson was busily attempting to shop around her Oz stories, with Neill’s illustrations, in Hollywood, and that both Ruth Plumly Thompson and John R. Neill were very much alive during development/filming. Using Neill’s images for costumes could have resulted in costly legal action – and Thompson, at least, was on the alert for any such possibilities. Under the circumstances using Denslow’s illustrations was both necessary and prudent.

Similarly, any of the many Oz productions in development today (or so rumor claims) would need to use either Denslow’s or Neill’s illustrations for inspiration – but cannot use any images or costumes from the 1939 film, since that’s still under copyright, or, for that matter, the recent Marvel Comics adaptation, without paying for the rights. (Which means, I guess, that if any of the planned films use the shoes, the shoes will go right back to their original color, silver, since the Ruby Shoes are an MGM thing.)

Oh, and since you don’t like Neill, allow me to strongly urge you to avoid looking at Frank Kramer’s and Dirk Gringhuis’ work.

“the final vote comes out almost exactly even—how desperate must the Ozites be to vote for an often bad tempered clothes stylist who likes to fight with chocolate?”

There is an explanation in the text. The Woggle Bug says there would be no suspense if everybody got to vote for whoever they wanted – Ozma would win in a landslide. Thus he had everybody line up and the first person would vote for Ozma, the second for Jenny Jump, and so on down the line. Not much of an election, really. More of a coin flip.

I guess you can tell Neill didn’t come up with the “ozlection” idea as there isn’t a single illustration for it.

It’s a odd book, all right. But some of the best illos Neill produced for an Oz book since Baum – although I understand one of the most spectacular (the light fairies on the roof of the palace) was pulled out of a drawer and repurposed – not that that bothers me, it’s lovely.

The Wiz did use the more authentic, if less recognizable, silver shoes. To be sure, Harlem isn’t Kansas, and 24-year-old teachers aren’t 6-8-year-old girls, but in some ways The Wiz is more true to the book. Above all, there is no suggestion that Oz is a dreamworld.