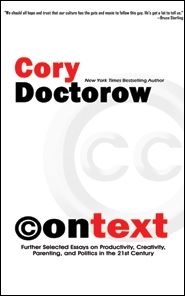

Your daily food for thought comes from a selection of essays written by Cory Doctorow from is book Context, out now from Tachyon Publications.

Discussing complex topics in an accessible manner, Cory Doctorow shares visions of a future where artists control their own destinies and where freedom of expression is tempered with the view that creators need to benefit from their own creations. From extolling the Etsy marketverse to excoriating Apple for dumbing-down technology while creating an information monopoly, each unique piece is brief, witty, and at the cutting edge of tech. Now a stay-at-home dad as well as an international activist, Doctorow writes as eloquently about creating internet real-time theater with his daughter as he does in lambasting the corporations that want to limit and profit from inherent intellectual freedoms.

Jack and the Interstalk: Why the Computer Is Not a Scary Monster

With a little common sense, parents have nothing to fear from letting young children share their screen time

“Daddy, I want something on your laptop!” These are almost invariably the first words out of my daughter Poesy’s mouth when she gets up in the morning (generally at 5 a.m.). Being a lifelong early riser, I have the morning shift. Being a parent in the 21st century, I worry about my toddler’s screen time—and struggle with the temptation to let the TV or laptop be my babysitter while I get through my morning email. Being a writer, I yearn to share stories with my two-year-old.

I can’t claim to have found the answer to all this, but I think we’re evolving something that’s really working for us—a mix of technology, storytelling, play, and (admittedly) a little electronic babysitting that let’s me get to at least some of my email before breakfast time.

Since Poe was tiny, she’s climbed up on my lap and shared my laptop screen. We long ago ripped all her favorite DVDs (she went through a period at around 16 months when she delighted in putting the DVDs shiny-side-down on the floor, standing on them, and skating around, sanding down the surface to a perfectly unreadable fog of microscratches). Twenty-some movies, the whole run of The Muppet Show, some BBC nature programmes. They all fit on a 32GB SD card and my wife and I both keep a set on our laptops for emergencies, such as in-flight meltdowns or the occasional restaurant scene.

I use a free/open source video player called VLC, which plays practically every format ever invented. You can tell it to eliminate all its user interface, so that it’s just a square of movable video, and the Gnome windowmanager in Linux lets me set that window as “Always on top.” I shrink it down to a postage stamp and slide it into the top right corner of my screen, and that’s Poesy’s bit of my laptop.

When she was littler, we’d do this for 10 or 20 minutes every morning while she went from awake to awake-enough-to-play. Now that she’s more active, she usually requests something—often something from YouTube (we also download her favourite YouTube clips to our laptops, using deturl.com), or she’ll start feeding me keywords to search on, like “doggy and bunny” and we’ll have a look at what comes up. It’s nice sharing a screen with her. She points at things in her video she likes and asks me about them (pausable video is great for this!), or I notice stuff I want to point out to her. At the same time, she also looks at my screen—browser windows, email attachments, etc.—and asks me about them, too.

But the fun comes when we incorporate all this into our storytelling play. It started with Jack and the Beanstalk. I told her the story one morning while we were on summer vacation. She loved the booming FEE FI FOE FUM! but she was puzzled by unfamiliar ideas like beanstalks, castles, harps, and golden eggs. So I pulled up some images of them (using Flickr image search). Later, I found two or three different animated versions of Jack’s story on YouTube, including the absolutely smashing Max Fleischer 1933 version. These really interested Poesy (especially the differences between all the adaptations), so one evening we made a Lego beanstalk and had an amazing time running around the house, play-acting Jack and the Beanstalk with various stuffed animals and such as characters. We made a golden egg out of wadded up aluminium foil, and a harp out of a coat-hanger, tape, and string, and chased up and down the stairs bellowing giant-noises at one another.

Then we went back to YouTube and watched more harps, made sure to look at the geese the next Saturday at Hackney City Farm, and now every time we serve something small and bean-like with a meal at home, there’s inevitably a grabbing up of two or three of them and tossing them out the window while shouting, “Magic beans! Magic beans! You were supposed to sell the cow for money!” Great fun.

Every parent I know worries about the instantaneously mesmerizing nature of screens for kids, especially little kids. I’ve heard experts advise that kids be kept away from screens until the age of three or four, or even later, but that’s not very realistic—at least not in our house, where the two adults do a substantial amount of work, socialising, and play from home on laptops or consoles.

But the laptop play we’ve stumbled on feels right. It’s not passive, mesmerised, isolated TV watching. Instead, it’s a shared experience that involves lots of imagination, physically running around the house (screeching with laughter, no less!), and mixing up story-worlds, the real world, and play. There are still times when the TV goes on because I need 10 minutes to make the porridge and lay the table for breakfast, and I still stand in faint awe of the screen’s capacity to hypnotise my toddler, but I wouldn’t trade those howling, hilarious, raucous games that our network use inspires for anything.

Teen Sex

My first young adult novel, Little Brother, tells the story of a kid named Marcus Yallow who forms a guerilla army of young people dedicated to the reformation of the U.S. government by any means necessary. He and his friends use cryptography and other technology to subvert security measures, to distribute revolutionary literature, to liberate and publish secret governmental memos, and humiliate government officials. Every chapter includes some kind of how-to guide for accomplishing this kind of thing on your own, from tips on disabling radiofrequency ID tags to beating biometric identity system to defeating the censorware used by your school network to control what kind of things you can and can’t see on the internet. The book is a long hymn to personal liberty, free speech, the people’s right to question and even overthrow their government, even during wartime.

Marcus is 17, and the book is intended to be read by young teens or even precocious tweens (as well as adults). Naturally, I anticipated that some of the politics and technology in the story would upset my readers. And it’s true, a few of the reviewers were critical of this stuff. But not many, not overly so.

What I didn’t expect was that I would receive a torrent of correspondence and entreaties from teachers, students, parents, and librarians who were angry, worried, or upset that Marcus loses his virginity about two-thirds of the way through the book (secondarily, some of them were also offended by the fact that Marcus drinks a beer at one point, and a smaller minority wanted to know why and how Marcus could get away with talking back to his elders).

Now, the sex-scene in the book is anything but explicit. Marcus and his girlfriend are kissing alone in her room after a climactic scene in the novel, and she hands him a condom. The scene ends. The next scene opens with Marcus reflecting that it wasn’t what he thought it would be, but it was still very good, and better in some ways than he’d expected. He and his girlfriend have been together for quite some time at this point, and there’s every indication that they’ll go on being together for some time yet. There is no anatomy, no grunts or squeals, no smells or tastes. This isn’t there to titillate. It’s there because it makes plot-sense and story-sense and character-sense for these two characters to do this deed at this time.

I’ve spent enough time explaining what this “plotsense and story-sense and character-sense” means to enough people that I find myself creating a “Teen transgression in YA literature FAQ.”

There’s really only one question: “Why have your characters done something that is likely to upset their parents, and why don’t you punish them for doing this?”

Now, the answer.

First, because teenagers have sex and drink beer, and most of the time the worst thing that results from this is a few days of social awkwardness and a hangover, respectively. When I was a teenager, I drank sometimes. I had sex sometimes. I disobeyed authority figures sometimes.

Mostly, it was OK. Sometimes it was bad. Sometimes it was wonderful. Once or twice, it was terrible. And it was thus for everyone I knew. Teenagers take risks, even stupid risks, at times. But the chance on any given night that sneaking a beer will destroy your life is damned slim. Art isn’t exactly like life, and science fiction asks the reader to accept the impossible, but unless your book is about a universe in which disapproving parents have cooked the physics so that every act of disobedience leads swiftly to destruction, it won’t be very credible. The pathos that parents would like to see here become bathos: mawkish and trivial, heavy-handed, and preachy.

Second, because it is good art. Artists have included sex and sexual content in their general-audience material since cave-painting days. There’s a reason the Vatican and the Louvre are full of nudes. Sex is part of what it means to be human, so art has sex in it.

Sex in YA stories usually comes naturally, as the literal climax of a coming-of-age story in which the adolescent characters have undertaken a series of leaps of faiths, doing consequential things (lying, telling the truth, being noble, subverting authority, etc.) for the first time, never knowing, really knowing, what the outcome will be. These figurative losses of virginity are one of the major themes of YA novels—and one of the major themes of adolescence—so it’s artistically satisfying for the figurative to become literal in the course of the book. This is a common literary and artistic technique, and it’s very effective.

I admit that I remain baffled by adults who object to the sex in this book. Not because it’s prudish to object, but because the off-camera sex occurs in the middle of a story that features rioting, graphic torture, and detailed instructions for successful truancy.

As the parent of a young daughter, I feel strongly that every parent has the right and responsibility to decide how his or her kids are exposed to sex and sexually explicit material.

However, that right is limited by reality: the likelihood that a high-school student has made it to her 14th or 15th year without encountering the facts of life is pretty low. What’s more, a kid who enters puberty without understanding the biological and emotional facts about her or his anatomy and what it’s for is going to be (even more) confused.

Adolescents think about sex. All the time. Many of them have sex. Many of them experiment with sex. I don’t believe that a fictional depiction of two young people who are in love and have sex is likely to impart any new knowledge to most teens—that is, the vast majority of teenagers are apt to be familiar with the existence of sexual liaisons between 17-year-olds.

So since the reader isn’t apt to discover anything new about sex in reading the book, I can’t see how this ends up interfering with a parent’s right to decide when and where their kids discover the existence of sex.

Nature’s Daredevils: Writing for Young Audiences

I know, at the end of the last column I promised that this issue I’d talk all about Macropayments, but that was before I found out that this was Locus’s special youngadult SF issue, and as I happen to be on tour with my first young-adult SF novel, Little Brother, I think I’d better put off Macros for a month a talk a little about what I’ve learned about writing for young people.

First of all, YA SF is gigantic and invisible. The numbers speak for themselves: a YA bestseller is likely to be moving ten times as many copies as an adult SF title occupying the comparable slot on the grownup list. Like many commercially successful things, YA is largely ignored by the power brokers of the field, rarely showing up on the Hugo ballot (and when was the last time you went to a Golden Duck Award ceremony?). Yet so many of us came into the field through YA, and it’s YA SF that will bring the next generation into the fold.

Genre YA fiction has an army of promoters outside of the field: teachers, librarians, and specialist booksellers are keenly aware of the difference the right book can make to the right kid at the right time, and they spend a lot of time trying to figure out how to convince kids to try out a book. Kids are naturals for this, since they really use books as markers of their social identity, so that good books sweep through their social circles like chickenpox epidemics, infecting their language and outlook on life. That’s one of the most wonderful things about writing for younger audiences—it matters. We all read for entertainment, no matter how old we are, but kids also read to find out how the world works. They pay keen attention, they argue back. There’s a consequentiality to writing for young people that makes it immensely satisfying. You see it when you run into them in person and find out that there are kids who read your book, googled every aspect of it, figured out how to replicate the best bits, and have turned your story into a hobby. We wring our hands a lot about the greying of SF, with good reason. Just have a look around at your regional con, the one you’ve been going to since you were a teenager, and count how many teenagers are there now. And yet, young people are reading in larger numbers than they have in recent memory. Part of that is surely down to Harry Potter, but on this tour, I’ve discovered that there’s a legion of unsung heroes of the kids-lit revolution.

These are booksellers like Anderson’s of Naperville, a suburb of Chicago. Anderson’s operates a lovely bookstore, the kind of friendly indie shop that we all have cherished memories of, but that’s not the main event. They also have a “book fair” business that is run out of a nearby warehouse. This involves filling trucks with clever, rolling bookcases that snap shut like a cigarette case, each one pre-stocked with carefully curated titles. These are schlepped out to schools across the Midwest, assembled in impromptu school-gym book fairs. This matters. It matters because you don’t go to the bookstore until you already know you love books. You need a gateway drug to get you hooked on the harder stuff. Traditionally, this was the non-bookstore retailer, the pharmacy, the supermarket. That was before distributorship consolidation took place in the wake of the rise of national, big-box retailers like Wal-Mart. The contraction in distribution led to a massive reduction in the number of titles stocked outside of bookstores across the land. Even as the bookstores got bigger and more elaborate, the vital induction system of finding the right book on the right spinner rack at the right age was collapsing. We know what happened next: the collapse of the midlist, massive mergers and acquisitions in publishing, the shuttering of many longstanding careers in the field. So when Anderson’s pulls up a truck outside your school and puts the books right there, where you can’t miss them, it starts to take back that vital territory that we lost 20 years ago, starts to bring kids back into the faith.

Writing for young people is really exciting. As one YA writer told me, “Adolescence is a series of brave, irreversible decisions.” One day, you’re someone who’s never told a lie of consequence; the next day you have, and you can never go back. One day, you’re someone who’s never done anything noble for a friend; the next day you have, and you can never go back. Is it any wonder that young people experience a camaraderie as intense as combat-buddies? Is it any wonder that the parts of our brain that govern risk-assessment don’t fully develop until adulthood? Who would take such brave chances, such existential risks, if she or he had a fully functional risk-assessment system?

So young people live in a world characterized by intense drama, by choices wise and foolish and always brave. This is a book-plotter’s dream. Once you realize that your characters are living in this state of heightened consequence, every plot-point acquires moment and import that keeps the pages turning.

The lack of regard for YA fiction in the mainstream isn’t an altogether bad thing. There’s something to be said for living in a disreputable, ghettoized bohemia (something that old-time SF and comics fans have a keen appreciation for). There’s a lot of room for artistic, political, and commercial expectation over here in lowstakes land, the same way that there was so much room for experimentation in other ghettos, from hip-hop to roleplaying games to dime-novels. Sure, we’re vulnerable to moral panics about corrupting youth (a phenomenon as old as Socrates, and a charge that has been leveled at everything from the waltz to the jukebox), but if you’re upsetting that kind of person, you’re probably doing something right.

Risk-taking behavior—including ill-advised social, sexual, and substance adventures—are characteristic of youth itself, so it’s natural that anything that co-occurs with youth, like SF or TV or video games, will carry the blame for them. However, the frightened and easily offended are doing a better job than they ever have of collapsing the horizons of young people, denying them the pleasures of gathering in public or online for fear of meteor-strike-rare lurid pedophile bogeymen, or on the pretense of fighting gangs or school shootings or some other tabloid horror. Literature may be the last escape available to young people today. It’s an honor to be writing for them.

Beyond Censorware: Teaching Web Literacy

The Problem

Control over the way kids use computers is a real political football, part of the wide-ranging debates over child pornography, bullying, sexual predation, privacy, piracy, and cheating.

And if those stakes weren’t high enough, consider this: The norms of technology use that today’s kids grow up with will play a key role in tomorrow’s workplace, national competitiveness, and political discourse.

Hoo-boy—poor kids!

The idea that kids can run technological circles around their elders is hardly new. In 1878, the newly launched Bell System was crashed by its operators, young messenger boys who’d been redeployed to run the nascent phone system and instead treated the nation’s fragile communications infrastructure as the raw material for a series of pranks and ill-conceived experiments.

Today, kids are still way ahead of the grownups who supposedly control their school and home networks. In my informal interviews, I’ve discovered again and again that kids are a bottomless well of tricks for evading network filters and controls, and that they propagate their tricks like crazy, trading them like bubble-gum cards and amassing social capital by helping their peers gain access to the whole wide Web, rather than the narrow slice that’s visible through the crack in the firewall.

I have to admit, this warms my heart. After all, do we want to raise a generation of kids who have the tech savvy of an Iranian dissident, or the ham-fisted incompetence of the government those dissidents are running circles around?

But I’m also a parent, and I know that it won’t be long before my daughter is using her network access to get at stuff that’s so vile, my eyes water just thinking about it. What’s more, she’s going to be exposed to a vast panoply of privacy dangers, from the marketing creeps who’ll track her around the Web to the spyware jerks who’ll try to infect her machine to the crazed spooks at agencies like the NSA who are literally out to wiretap the entire world.

Add to that the possibility that the disclosures she makes on the network are likely to follow her for her whole life, every embarrassing utterance preserved for eternity, and it’s clear that there’s a problem here.

But I think I have the solution. Read on.

The Solution: No Censorware

Let’s start by admitting that censorware doesn’t work. It catches vast amounts of legitimate material, interfering with teachers’ lesson planning and students’ research alike.

Censorware also allows enormous amounts of bad stuff through, from malware to porn. There simply aren’t enough prudes in the vast censorware boiler-rooms to accurately classify every document on the Web.

Worst of all, censorware teaches kids that the normal course of online life involves being spied upon for every click, tweet, email, and IM.

These are the same kids who we’re desperately trying to warn away from disclosing personal information and compromising photos on social networks. They understand that actions speak louder than words: If you wiretap every student in the school and punish those who try to get out from under the all-seeing eye, you’re saying, “Privacy is worthless.”

After you’ve done that, there’s no amount of admonishments to value your privacy that can make up for it.

On the other hand, censorware provides a brilliant foil for a curriculum unit that teaches 21st century media literacy in ways that are meaningful, informative, and likely to make kids and the networks they use better and safer.

The Lesson Plan

Here’s my outline for a curriculum of media literacy (addressed to the students):

1) Work with your teacher to select 30 important keywords relevant to your curriculum. Check the top 50 results for each on Google or another popular search engine, and record how many are blocked by your school firewall.

A study undertaken by the Electronic Frontier Foundation in 2003 found that up to 50 percent of pages relevant to common U.S. curricula were blocked by various commercial censorware products.

In this exercise, students learn comparative searching, statistical analysis, and gain greater familiarity with their own curricula.

Further study includes identifying those subjects that are more apt to be blocked—for example, sites relevant to reproductive health, breast cancer, racism, etc.

2) Keep a log of the inappropriate pages you encounter while browsing, including pornographic pages, adware, malware, and so on. Compile a chart showing how many times a day your school’s censorware fails to protect the students in your class.

More stats here, introducing the idea of both “false positive” and “false negative.” This also opens the debate on what is and is not a “bad” page, demonstrating how subjective this kind of classification is.

3) Interview your teachers about the ways that censorware interferes with their teaching.

Every teacher has stories about cueing up a video in the morning to use after lunch, only to discover that it’s been blocked in the interim and blown their lesson-plan. Gathering these stories helps students understand that censorware affects everyone in the school, even the teachers who are supposedly in charge of their care and education.

4) Interview your fellow students about the ways that they defeat censorware (e.g., looking for unblocked proxies by searching for “proxy” on Google and moving to the 75th page of results, so deep that it’s unlikely to have been catalogued by the censorware companies; or evading blocks on message-boards by using random, ancient blog-posts’ message areas to conduct secret conversations).

Discuss “security through obscurity” and “security theater,” and whether a security system can be said to work if it can be so trivially evaded by kids.

5) Research the corporate reputation and practices of the censorware company that supplies your school.

Many censorware companies have very dirty hands. For example, SmartFilter (now a division of McAfee) is a high-profile supplier of censorware to repressive regimes. SmartFilter’s software was recently used in the United Arab Emirates to block news about a member of the royal family who had been video-recorded brutally torturing a businessassociate. Learning to research the credibility and conduct of people who provide information on the internet is the key to understanding which information can and cannot be trusted.

6) Contact the censorware company and ask for the criteria by which it rates pages. Ask for the reason that the false positives identified in step 1 were classified as objectionable.

7) Research how to file a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request and use the procedure to discover how much your school or school board spends on censorware.

Imagine what kind of nation we’d have if every high-school graduate knew how to file an FOIA request—once you’ve learned this, no civics, history, or politics class will ever be the same.

8) Bonus marks: Present your research to your board of education.

Get on the agenda for an upcoming meeting. Present your findings: Our censorware fails to protect us in these ways; it interferes with our education in these ways; it is technically insufficient in these ways; the company is unworthy of public funds in these ways; the money could be spent on this, that, and the other. Thank you.

A unit like this, undertaken as a year-long project, would graduate a generation of students who understand applied statistics, risk and security, civic engagement, legal procedures, and the means by which you can evaluate the information you receive.

What more could any society ask for?

Writing in the Age of Distraction

We know that our readers are distracted and sometimes even overwhelmed by the myriad distractions that lie one click away on the internet, but of course writers face the same glorious problem: the delirious world of information and communication and community that lurks behind your screen, one alt-tab away from your word-processor.

The single worst piece of writing advice I ever got was to stay away from the internet because it would only waste my time and wouldn’t help my writing. This advice was wrong creatively, professionally, artistically, and personally, but I know where the writer who doled it out was coming from. Every now and again, when I see a new website, game, or service, I sense the tug of an attention black hole: a time-sink that is just waiting to fill my every discretionary moment with distraction. As a co-parenting new father who writes at least a book per year, half-a-dozen columns a month, ten or more blog posts a day, plus assorted novellas and stories and speeches, I know just how short time can be and how dangerous distraction is.

But the internet has been very good to me. It’s informed my creativity and aesthetics, it’s benefited me professionally and personally, and for every moment it steals, it gives back a hundred delights. I’d no sooner give it up than I’d give up fiction or any other pleasurable vice.

I think I’ve managed to balance things out through a few simple techniques that I’ve been refining for years. I still sometimes feel frazzled and info-whelmed, but that’s rare. Most of the time, I’m on top of my workload and my muse. Here’s how I do it:

-

Short, regular work schedule

When I’m working on a story or novel, I set a modest daily goal—usually a page or two—and then I meet it every day, doing nothing else while I’m working on it. It’s not plausible or desirable to try to get the world to go away for hours at a time, but it’s entirely possible to make it all shut up for 20 minutes. Writing a page every day gets me more than a novel per year—do the math—and there’s always 20 minutes to be found in a day, no matter what else is going on. Twenty minutes is a short enough interval that it can be claimed from a sleep or meal-break (though this shouldn’t become a habit). The secret is to do it every day, weekends included, to keep the momentum going, and to allow your thoughts to wander to your next day’s page between sessions. Try to find one or two vivid sensory details to work into the next page, or a bon mot, so that you’ve already got some material when you sit down at the keyboard.

-

Leave yourself a rough edge

When you hit your daily word-goal, stop. Stop even if you’re in the middle of a sentence. Especially if you’re in the middle of a sentence. That way, when you sit down at the keyboard the next day, your first five or ten words are already ordained, so that you get a little push before you begin your work. Knitters leave a bit of yarn sticking out of the day’s knitting so they know where to pick up the next day—they call it the “hint.” Potters leave a rough edge on the wet clay before they wrap it in plastic for the night—it’s hard to build on a smooth edge.

-

Don’t research

Researching isn’t writing and vice-versa. When you come to a factual matter that you could google in a matter of seconds, don’t. Don’t give in and look up the length of the Brooklyn Bridge, the population of Rhode Island, or the distance to the Sun. That way lies distraction—an endless click-trance that will turn your 20 minutes of composing into a half-day’s idyll through the web. Instead, do what journalists do: type “TK” where your fact should go, as in “The Brooklyn Bridge, all TK feet of it, sailed into the air like a kite.” “TK” appears in very few English words (the one I get tripped up on is “Atkins”) so a quick search through your document for “TK” will tell you whether you have any fact-checking to do afterwards. And your editor and copyeditor will recognize it if you miss it and bring it to your attention.

-

Don’t be ceremonious

Forget advice about finding the right atmosphere to coax your muse into the room. Forget candles, music, silence, a good chair, a cigarette, or putting the kids to sleep. It’s nice to have all your physical needs met before you write, but if you convince yourself that you can only write in a perfect world, you compound the problem of finding 20 free minutes with the problem of finding the right environment at the same time. When the time is available, just put fingers to keyboard and write. You can put up with noise/ silence/kids/discomfort/hunger for 20 minutes.

-

Kill your word-processor

Word, Google Office, and OpenOffice all come with a bewildering array of typesetting and automation settings that you can play with forever. Forget it. All that stuff is distraction, and the last thing you want is your tool second-guessing you, “correcting” your spelling, criticizing your sentence structure, and so on. The programmers who wrote your word processor type all day long, every day, and they have the power to buy or acquire any tool they can imagine for entering text into a computer. They don’t write their software with Word. They use a text-editor, like vi, Emacs, TextPad, BBEdit, Gedit, or any of a host of editors. These are some of the most venerable, reliable, powerful tools in the history of software (since they’re at the core of all other software) and they have almost no distracting features—but they do have powerful search-and-replace functions. Best of all, the humble .txt file can be read by practically every application on your computer, can be pasted directly into an email, and can’t transmit a virus. -

Realtime communications tools are deadly

The biggest impediment to concentration is your computer’s ecosystem of interruption technologies: IM, email alerts, RSS alerts, Skype rings, etc. Anything that requires you to wait for a response, even subconsciously, occupies your attention. Anything that leaps up on your screen to announce something new occupies your attention. The more you can train your friends and family to use email, message boards, and similar technologies that allow you to save up your conversation for planned sessions instead of demanding your attention right now helps you carve out your 20 minutes. By all means, schedule a chat—voice, text, or video—when it’s needed, but leaving your IM running is like sitting down to work after hanging a giant “DISTRACT ME” sign over your desk, one that shines brightly enough to be seen by the entire world.

I don’t claim to have invented these techniques, but they’re the ones that have made the 21st century a good one for me.

Context © Cory Doctorow 2011