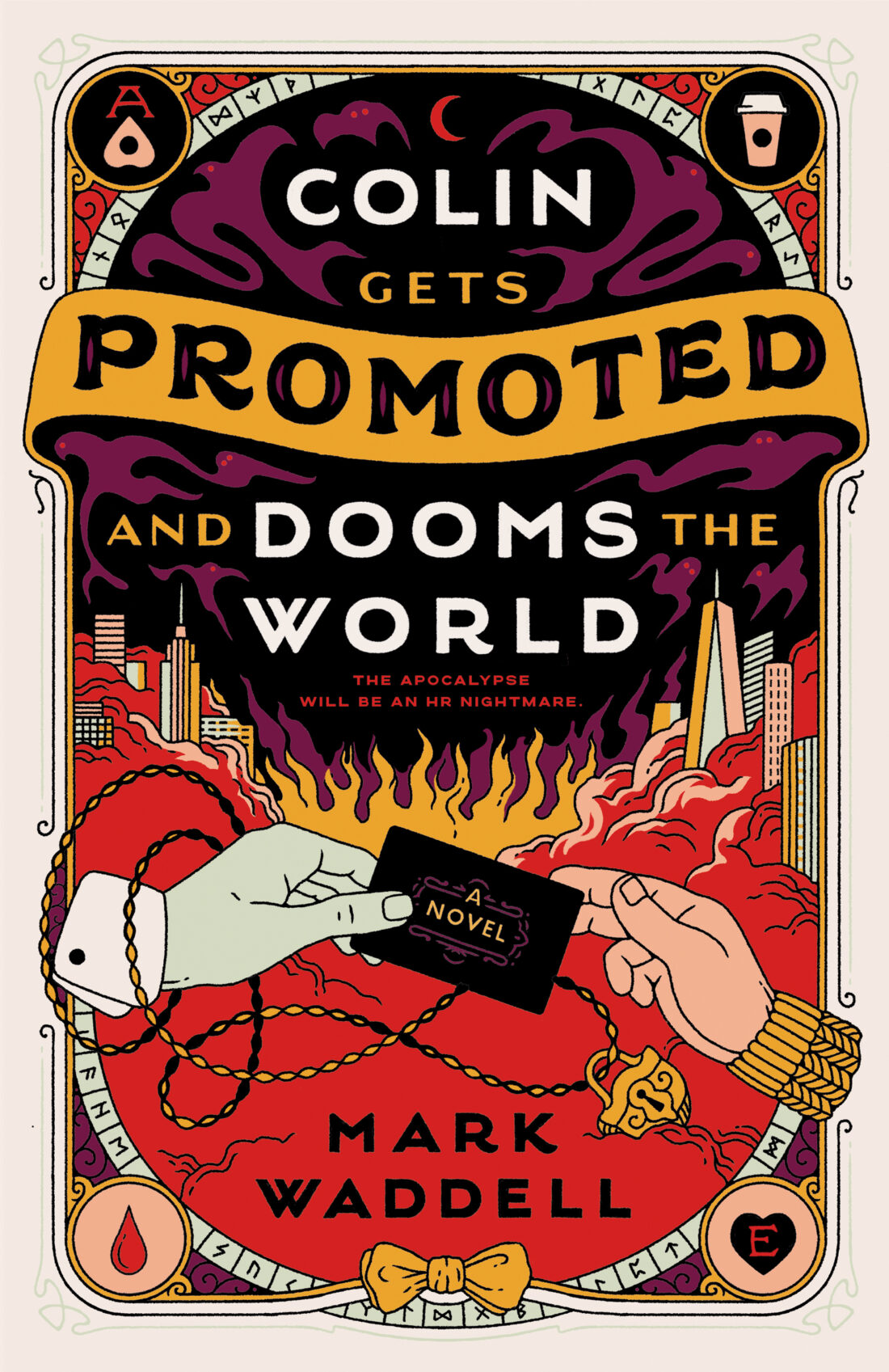

We’re thrilled to share the cover and preview the first chapter from Mark Waddell’s Colin Gets Promoted and Dooms the World—forthcoming October 7, 2025 from Ace, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

WARNING! Under no circumstances must employees strike a deal with unauthorized personnel on Dark Enterprises property. Such behavior could result in death… or the end of the world.

Colin is a low-level employee at Dark Enterprises, a Hell-like multinational corporation solving the world’s most difficult problems in deeply questionable ways. After years of toiling away in a cubicle, he’s ready to climb the corporate ladder and claim the power he’s never had.

The only problem is, he’s pretty sure he’s about to be terminated. Like, terminated. That’s tough, because his BFF has just set him up with a great guy. In fact, maybe he’s a little too great. And asks a lot of questions…

When Colin meets a shadowy figure promising him his heart’s deepest desire, he can’t resist the urge to fast-track his goals. In return for a small, unspecified favor, he asks for the one thing that will improve his life: a promotion.

But that small favor unleashes an ancient evil. People in New York are disappearing, the world might be ending, and Management is starting to notice. Getting to the top is never easy, and now it’s up to Colin to save the world. It’s the ultimate power move, after all.

Mark Waddell grew up on the cold, windswept prairies of western Canada and later earned a Ph.D. in the history of science, medicine, and technology from the Johns Hopkins University. After teaching at Michigan State University for fifteen years, he and his husband moved to Vancouver Island. When not writing, he plays the viola in the Civic Orchestra of Victoria, walks his dogs on the beach, and slays fearsome monsters in Dungeons & Dragons.

Buy the Book

Colin Gets Promoted and Dooms the World

One

One week before I accidentally doomed all of humankind, I found myself staring at a huge photo of a possum, little pink paws outstretched as it leaped from a tree branch. Written above was the encouraging if implausible phrase Nothing is im‑POSSUM‑able!

“I have some concerns about your performance, Colin.”

My insides tied themselves into painful knots at those dreaded words. “My performance?” I repeated as I tore my gaze from the motivational poster and focused instead on my boss.

Ms. Kettering studied me from the other side of her desk. She wore a teal blue polyester skirt suit over a cream‑colored blouse with a pussycat bow tied beneath her chin, her hair arranged in its usual bouffant of tight brown curls. Enormous square‑shaped glasses with green‑tinted acrylic frames called attention to her bright purple eye shadow, apparently chosen to match her chunky plastic earrings. Her coral‑tinged lips were turned upward in a friendly smile, which might have been more reassuring if she hadn’t worn the same expression the other day while telling us all that Alonzo had disappeared “somewhere between floors three and six” and wouldn’t be coming back.

“Last week, Sunil found four mistakes in the reports you filed.” She shook her head as she glanced down at the file in front of her. All around us, the walls of her office were papered with cute animals photographed in precarious circumstances, urging me to hang in there or face down any challenge or triumph against impossible odds. “In addition, some of those reports were filed late. I’m sur‑ prised, Colin. You know we take carelessness very seriously here in Human Resources.”

My palms were sweating, and I rubbed them against my khakis as a dark and terrifying suspicion started to coalesce in my mind. “I can explain, Ms. Kettering.”

Her eyebrows went up as she waited.

Your assistant is sabotaging me, I almost said. He’s trying to get me killed. Only, that would never work. Kettering liked Sunil. Everyone liked Sunil. “I’ve been engaged in extra work for the department,” I told her instead. “Like cleaning the drains in the extraction suites. There’re always stray teeth lodged in there.” I paused and took a deep breath, trying not to babble. She knew perfectly well that teeth tended to go everywhere during some of our more vigorous procedures. “I’ve also been compiling the weekly extraction schedules. That’s taking up a lot of my time.”

Ms. Kettering’s smile curved into a tiny frown. “Those tasks aren’t your responsibility, Colin.”

Unfortunately, Sunil had made them my responsibility. He controlled our weekly assignments, and since rejecting his sleazy advances I’d been swamped with menial and unnecessary work. “I just care about Human Resources so much,” I said with a nervous smile and a what can you do? shrug. Maybe I could spin Sunil’s petty revenge as me being a proactive employee.

Behind those enormous glasses, Ms. Kettering’s eyes were cold. They always were, though, no matter how friendly her smile or how warm her breathy, high‑pitched voice. That was how you knew she was dangerous. “Your loyalty is commendable,” she said, “but we can’t have inefficiency here. Mistakes in those reports mean we might miss our quotas, and failure to meet our quotas will result in a visit from Management.” She didn’t quite shiver but took a moment to rearrange the papers on her desk as if collecting herself.

I did shiver. Visits from Management were rare but almost al‑ ways involved protracted screaming and sudden disappearances.

“In light of your two years with the company,” Ms. Kettering went on after a small pause, “you will have one week to adjust your performance.” Her usual smile returned, though her eyes never changed. “If we don’t see sufficient improvement, however, I will have no choice but to recommend you for early retirement.”

My breath caught. That meant an exit interview with the Firing Squad and then a one‑way trip in an unmarked van. Swallowing noisily, I jerked my head up and down in a nod. “I’ll do better,” I said in a hoarse voice.

“I hope you do, Colin. I’d hate to lose such a valued employee.”

* * *

Once I was dismissed, I leaned against the wall outside Ms. Kettering’s office and let out a long, shaky breath. Early retirement. I’d known other employees to vanish mysteriously, replaced by smiling, conscientious workers who didn’t ask questions about their predecessors, but I’d never imagined I would be in the same boat. I worked hard. I believed in this company. And yet here I was, marked for death.

Pushing off from the wall, I headed for my cubicle on trembling legs. I needed to get to work. Around me stretched the bullpen at the heart of the sixth floor, dozens of cubicles occupied by HR employ‑ ees entering data or filing reports. No one looked at me as I walked past, but then, no one ever looked at me. That didn’t matter now, though. The clock was ticking down what might be the last week of my life, and I needed to show Ms. Kettering that I wasn’t ready for early retirement.

As I grabbed the clipboard waiting on my desk, someone shrieked off in the distance, the sound soothing, familiar, like ambient white noise. Moments later, I heard the unmistakable slapping of bare feet against carpeted floors as a subject tried to escape some‑ where in the warren of extraction suites that surrounded the cubicle farm. Consulting the morning schedule, I wondered absently if they would make it this far. Last week, in a brief respite from the monotony of data analysis, a young man with gang tattoos had burst into the bullpen and run around shouting for help until Security tasered him. He’d convulsed all over Beverly’s desk, and it had taken her most of the afternoon to put everything back in place.

Moving with determination, I made a beeline for the first extraction suite on my schedule. It was my job to perform twice‑daily inspections of our extractions and compare them with our projected quotas. There was nothing exciting about it, just an endless succession of spreadsheets and mind‑numbing reams of numbers, but at least the inspections got me out of the stale, unfriendly environs of the cubicle farm. Besides, Human Resources was important—as Ms. Kettering reminded us all the time, without the resources we extracted from our human subjects the entire company would grind to a halt.

The first extraction suite was small and brightly lit, all gleaming white walls and polished floors, and the cool air smelled of antiseptic and sadness when I slipped quietly through the door. At the room’s center stood a padded chair, and strapped to it was an older white man who looked like retired military: graying brush cut, square jaw, faded tattoos on his biceps. He was staring into a mirror that had been suspended from the ceiling, its silvery glass blackened with age, gilt flaking from its ornate frame. He didn’t have a choice, actually—a strap across his forehead kept his head immobile while ophthalmic speculums held his eyelids open. I had no idea what he was seeing in the mirror, but it would be a source of profound grief, whatever it was. Tears ran freely from his eyes, rolling down his cheeks and into a pair of tiny glass containers held to his face by another strap across his mouth. I bent down to check the volume collected so far and heard him whimpering softly as he wept.

I made a note on my clipboard, then nodded to the black‑clad technician monitoring the extraction before letting myself out. Tears shed by the grieving had all kinds of uses, and those collected from people who rarely cried were especially potent. I knew better than to judge from appearances—maybe that guy watched Lifetime movies and sobbed at schmaltzy commercials—but my guess was that we were probably getting some really good stuff in there. The folks in Supplies and Procurement should be happy about that.

I moved a little farther down the corridor, working my way clockwise, and stopped outside another door, peering through its rectangular window. This room looked much like the first: another chair, another person strapped to it. This time it was a middle‑aged Latinx woman who appeared to be screaming at the top of her lungs, though I couldn’t hear anything. Her bulging eyes were fixed on the trio of snakes that coiled and slid across her body, their mottled scales shining dully in the fluorescent light as they moved, tongues flickering across the woman’s immobilized form as if they could taste her fear. On the floor at her feet sat a wooden cube lacquered a brilliant crimson, its lid open to reveal an unsettling darkness within. That darkness grew deeper and blacker as I watched, absorbing the sound of her terror. After she’d screamed herself hoarse—she had another eight minutes or so, I judged—the box would be taken upstairs to Research and Development. They must be working on something big; this was the third batch of human screams they’d requested this week.

It took less than an hour to finish my inspections. We were on track to meet our weekly targets, though at this rate of extraction we risked reducing our subjects to gibbering wrecks of their former selves. Still, as Ms. Kettering liked to say, you couldn’t run a multi‑national corporation without breaking a few people. As I headed back to my cubicle, I wondered if I could send my reports to her directly. That might help with—

“How was your meeting with Kettering?”

I turned and found Sunil leaning casually against a cubicle wall, hands in pockets and a smug smile on his handsome face. Everything about him screamed success, from the expert tailoring of his crisp white shirt to the understated but pricey Rolex on his wrist. Not too long ago, my stomach would have pirouetted at the sight of him. Now it clenched painfully.

“Ms. Kettering said that my reports had mistakes in them,” I told him, trying to keep my voice steady.

He tsked softly, shaking his head. “Careless of you, bro.”

My face heated. “I triple‑check every report. I don’t let them go out with mistakes in them.”

“Oh, but you did.” Pushing himself off the cubicle, he sauntered closer, hazel eyes shining with malicious glee. “I guess you’re just not cut out for this job.”

I’d been so thrilled when Sunil started paying attention to me. He would stop by my cubicle to compliment my workflow or the granularity of my reports (I’ve always prided myself on my granularity). Leaning over me to look at the numbers on my computer screen, so close that I could feel the heat from his body, he’d brush his hand against my shoulder while commenting on the way I organized my spreadsheets. Who wouldn’t fall for that? Then, one day, he cornered me in the bathroom. I was on the fast track to bigger things, he told me. He could put in a good word with Ms. Kettering, maybe even set me up for a promotion. I just had to do him a couple of favors.

Then he pushed me into a stall and tried to force me to my knees. “Why are you doing this?” I demanded now. “She’s considering”—

I stopped abruptly, then glanced around as I lowered my voice—“early retirement. Is this because I wouldn’t… ?”

His smile vanished as if snuffed out. “Don’t flatter yourself.”

“That’s it, isn’t it? You thought I’d do whatever you wanted.”

He leaned closer to me. “I’m a ten, Colin,” he said, voice soft and cold. “And you?” He ran a contemptuous gaze across my striped bow tie and my Monday cardigan and my cheap khakis. “You’re a four. On a good day.”

Ignoring a sour twist of hurt, I snapped back, “If you’re so amazing, Sunil, why are you still languishing here in HR? Four years as Ms. Kettering’s assistant, and not even a hint of a promotion. It’s pathetic.”

Straightening, he curled his lip in a faint sneer. “You know what’s pathetic? A data analyst with a week to live. Get back to work.”

I watched helplessly as he walked away. This couldn’t be happening.

People were staring at me from their cubicles. How much had they heard? Head down, I hurried back to my desk. I had a report to compile. You can do this, I kept telling myself. You can save your job. I needed to go around Sunil and show Ms. Kettering that I deserved to be there.

Before I sent off the report, I checked it five times for mistakes. Then I emailed it directly to Ms. Kettering. Leaning back in my chair, I exhaled slowly. It was going to be okay. Once I’d taken the threat of early retirement off the table, I could figure out how to handle the Sunil situation.

My computer dinged and an email from Ms. Kettering appeared in my inbox. Heart pounding, I clicked it open and found a single, terse sentence: Reports go to Sunil. She’d copied him as well.

Less than five minutes later, I got an email from Sunil. Please see attached, it read. Then, below, These errors are unacceptable. Numb, I opened the attached spreadsheet. He’d taken the time to circle in red the changes he’d made to my report.

My heart, fluttering somewhere in my throat, plummeted into my stomach when I saw that he’d copied Ms. Kettering.

I might as well give up now. I was done.

Excerpted from Colin Gets a Promotion and Dooms the World, copyright © 2025 by Mark Waddell. Excerpted by permission of Ace. All rights reserved.