Ji-won’s hunger and rage deserve to be sated…

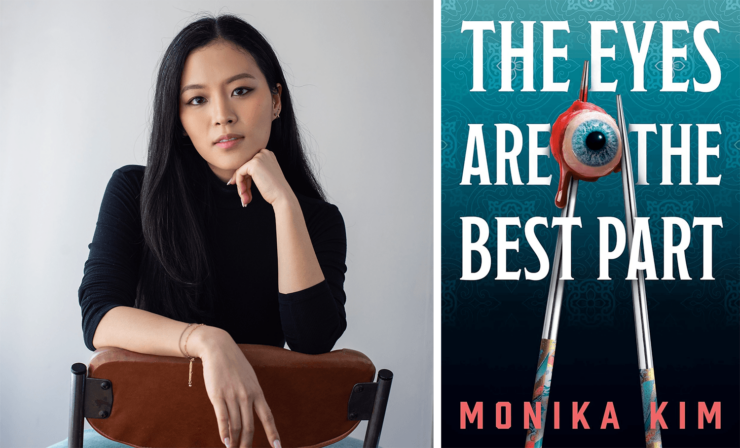

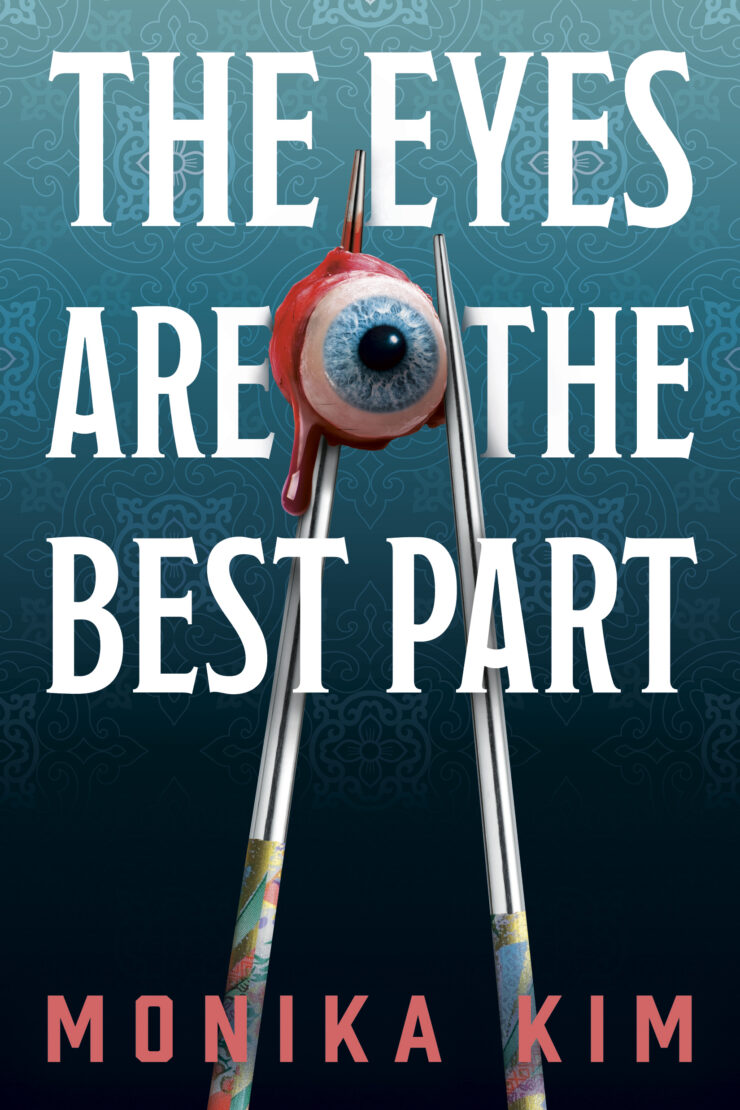

We’re thrilled to share the cover and preview an excerpt from Monika Kim’s debut horror novel The Eyes Are the Best Part, a story of a family falling apart and trying to find their way back to each other—available on June 25, 2024 from Erewhon Books.

A brilliantly inventive, subversive novel about a young woman unraveling, Monika Kim’s The Eyes Are the Best Part is a story of a family falling apart and trying to find their way back to each other, marking a bold new voice in horror that will leave readers mesmerized and craving more.

Ji-won’s life tumbles into disarray in the wake of her Appa’s extramarital affair and subsequent departure. Her mother, distraught. Her younger sister, hurt and confused. Her college freshman grades, failing. Her dreams, horrifying… yet enticing.

In them, Ji-won walks through bloody rooms full of eyes. Succulent blue eyes. Salivatingly blue eyes. Eyes the same shape and shade as George’s, who is Umma’s obnoxious new boyfriend. George has already overstayed his welcome in her family’s claustrophobic apartment.

He brags about his puffed-up consulting job, ogles Asian waitresses while dining out, and acts condescending toward Ji-won and her sister as if he deserves all of Umma’s fawning adoration. No, George doesn’t deserve anything from her family. Ji-won will make sure of that.

For no matter how many victims accumulate around her campus or how many people she must deceive and manipulate, Ji-won’s hunger and her rage deserve to be sated.

Buy the Book

The Eyes Are the Best Part

Monika Kim said,

“I was absolutely blown away when I saw the cover for the first time. It really captures the heart of the work—the subversion of the white male gaze by an Asian American woman—and I love all of the thoughtful, intricate details that artist Samira Iravani included. A huge thank you to Samira and the incredible team at Erewhon Books!”

Monika Kim is the author of The Eyes Are the Best Part. Monika graduated from the University of California, Davis, with a B.A. in Communication. Since 2016, she has been working for an environmental agency based in Southern California. In her current role, Monika’s work is focused on environmental justice and assisting underserved communities through outreach and youth education programs. Monika is passionate about the environment and climate justice. Through her books, she seeks to raise awareness on the Asian-American experience as well as on feminist issues. In her free time, Monika likes to try new foods, read, play video games, travel, and take pictures. Monika is a second-generation Korean-American living in Los Angeles’s Koreatown, where she resides with her family and her tuxedo cat, Velvet. She learned about eating fish eyes and other Korean superstitions from her mother, who immigrated to California from Seoul in 1985.

George has picked a Chinese restaurant that we’ve never heard of. When the three of us arrive, it’s a little after 12 p.m., and the parking lot is empty. The only other car there is a Ford truck that my mother points at. “George’s car,” she says. The truck looks new, and as we walk by it, I see a bumper sticker on the back. I’M REPUBLICAN BECAUSE WE CAN’T ALL BE ON WELFARE.

Before we step inside the restaurant, Umma flutters around Ji-hyun and me like a butterfly in a garden. She fixes our rain-soaked hair and pulls invisible threads from our clothing. She’s nervous. I fix her lipstick for her and wipe away the smudges of mascara around her eyes.

“Do I look okay?” she asks.

“You look great,” I respond, without thinking.

We walk through the swinging doors. The smiling hostess leads us into a private room where George is waiting. It’s big enough to fit twenty people, and when I see him sitting alone in such a big space, I snort. The image is ridiculous. He’s like a king sitting on his throne, waiting for his subjects to enter.

I don’t know what I expected, but George is completely ordinary. He looks like every other middle-aged white man I’ve seen. He’s short, only a head or two taller than Umma, with a full head of sandy brown hair, bushy eyebrows, and thin lips that recede into his mouth every time he smiles. His nose is upturned, and I can see the hair inside peeking out. When he moves, the papery skin around his neck hangs precariously off his chin. If he passed me on the street, I would never take a second look. He glances down at his watch. I follow his eyes. It’s a Rolex. I try not to show my surprise. “You guys are late.”

“George! Honey! I’m sorry!” Umma screeches. She pushes past us to embrace him, her fake Chanel bag swinging violently on her shoulder. To our disgust, George grabs our mother by the shoulders and plants a sloppy, open-mouthed kiss right on her lips. When they pull apart, there’s a smear of red across his mouth. Umma snatches a napkin from the table and wipes it away. At least she has the decency to look embarrassed. Never once have I seen my own parents kiss.

“Sorry,” he says, grinning. “I was excited to see your mother.” Neither Ji-hyun nor I respond. George rubs my mother’s back and as he does, his forehead creases with concern. “You guys are soaked! What happened? Did you go for a jog in the rain?”

“We didn’t have an umbrella,” Ji-hyun mutters.

“This won’t do,” George says. He unzips his jacket and wraps it around Umma’s shoulders. “Hold on. Let me go look in my truck. I think I have some extra clothes in there for the girls—”

“We’re fine,” I say, shaking my head.

He admonishes my mother, though his voice is gentle. “You’re going to catch a cold like this. You should have called me. I would have been happy to come to your car with the umbrella to get you guys. When the waitress comes, I’ll ask her to turn up the heater.” Finally, he turns to Ji-hyun and me, reaching out to shake our hands.

“It’s so great to meet you lovely girls,” he says, looking directly at me. “You’re Ji-hyun, right?”

He says “Ji-hyun” like he’s talking through a mouthful of gravel. From his mouth, my sister’s name is garbled, almost unintelligible.

“No, no,” Umma laughs. “That’s Ji-won. Don’t you remember? I showed you those pictures the other day.”

“I remember. Ji-won.” He doesn’t do any better with my name, saying “won” as though I’m a prize hanging on the wall at a county fair.

“You’re saying our names wrong,” Ji-hyun interrupts. Her tone is flat and unamused.

Umma glares at her. Even though George is smiling, I can tell he’s not happy with my sister. The edges of his weak lips tug downward, leaving him in a pained grimace. Already I know that he’s a man who isn’t used to being corrected. “Okay. How should I say them then?” It’s obvious that he’d rather be doing anything other than standing here in front of us, being schooled by a fifteen-year-old girl.

“The first syllable is more like the word ‘genius,’” she explains. “And you’re saying ‘won’ too harshly. It’s more of an ‘uh’ sound. Ji-won.”

George’s forehead is the first part of his face that turns red. The color sweeps downward until it reaches his neck. Nobody says anything; Umma glances nervously from Ji-hyun’s face to his. After what seems like an eternity, George says, “I see. Thanks for letting me know.” His voice is measured, polite. It doesn’t match his expression. “You know, I learned a lot of Korean when I was back in Seoul, but it’s been such a long time… and to tell you the truth, pronunciation isn’t my strong suit. If it bothers you that much, I can give you both nicknames.”

Ji-hyun’s eyes narrow. “Nicknames?”

“Yes. You can be JH, and you—” He points at me with his index finger. “I’ll call you JW.”

Ji-hyun opens her mouth to argue, but Umma intervenes. She picks up the haphazardly stacked menus from the middle of the table and slams them down. The plastic covers meet the wood with a loud slap.

“That’s enough,” Umma says. “Why don’t we order some food? I’m starving.” She leads Ji-hyun to a chair far from George and seats me in between them. The tension hangs in the air. We’re all cognizant of it. In an attempt to smooth things over, our mother turns to George and starts a conversation.

It’s awkward, listening to them talk to each other. Umma’s English isn’t very good. When she has the occasional English-only customer at the grocery store, she can manage. However, more complicated things like filling out forms or making appointments are downright impossible for her to do alone. To us she speaks only Korean, and when there are words that Ji-hyun and I don’t understand, she uses the translation app on her phone.

It quickly becomes obvious that our mother has exaggerated George’s ability to speak Korean. We can’t understand a single thing he’s saying. And he was right about his pronunciation. It’s horrible. His accent turns our once-familiar words into a different dialect entirely, their meanings blurred under the heaviness of his tongue. But George doesn’t notice. He’s pleased with himself, as if we should be impressed by his butchering of our language.

“Ah-nuhl moe-hat-sohn?” George asks us. It takes me a second to interpret what he’s trying to say, and it seems I’m the only one who understands. He’s asking, What did you do today? But Ji-hyun looks bewildered, and it’s obvious Umma has no clue either. She smiles and nods before saying something completely unrelated.

“I like the Chinese food,” she says in her broken English. “Good job.”

George frowns. “No, no,” he says. He tries again. “Ah-noor mah-hae-sooh?”

“Chinese,” Umma says loudly. She motions at the menu. “You know tangsuyuk?”

My cheeks burn. “Umma, he’s asking what we did today. He’s not talking about the food.”

“Oh!” My mother brightens up. “Oh-neul mo-haessuh-yo,” she says, correcting him. George tries to imitate her, his lips puckering, but after a few seconds he throws up his hands in exasperation.

It’s not surprising at all when their conversation comes to a standstill again a short while later. They try to understand each other, but these attempts are futile. They talk in circles without making much sense. Whenever this happens, Ji-hyun and I are forced to intervene and interpret for them. Our only role in this strange play, it seems, is interpreter.

How is it possible that they’ve been seeing each other all this time when they can’t even communicate? I envision them out and about together, grunting and pointing their hands at each other like cavemen.

“They’re saying it’s going to be pouring for the next few days,” George says.

“Pouring?” Umma asks, perplexed. She reaches for the pitcher of water in the middle of the table.

“No,” George says. He grabs her wrist to stop her. “Pouring.” Umma’s expression remains puzzled, and he raises his hands and wiggles his fingers in a downward motion. “Like rain.”

“Rain? Pouring?”

“Umma,” I interject, unable to hide my frustration. “He means it’s going to be raining a lot for the next few days. That’s what pouring means—”

“I know,” my mother says, waving impatiently and cutting me off. “I know.”

I roll my eyes. George puts his arm around Umma and squeezes her.

“You’ll have to take my umbrella when you go. I think I might have an extra one in the car, too. Take both of them.” Hearing this, Umma’s face lights up. There is so much happiness in her expression that I feel a sharp twist in my gut.

There is a quiet knock at the door. George yells, “Come in,” and it slides open, revealing our waitress, a slim Asian woman dressed in a red-and-gold embroidered qipao. She bows at each of us in turn before stepping inside. Her jet-black hair is tightly coiled into a neat bun at the top of her head; a single red chopstick—the same shade as the qipao—pokes out from the middle.

George’s eyes widen when she walks in. He rakes his gaze over her body, stopping at the soft mounds of her chest. His boldness repulses me.

“Thank goodness you’re here,” he says. “We’re starving.”

Disgusting.

The waitress giggles, covering her mouth. Rather than be upset at his obvious attempts at flirting, my mother is chuckling, her head nestled comfortably on George’s shoulder. How is it that she hasn’t detected everything wrong with this scenario? I peek at Ji-hyun. She too is unamused.

“What would you like to order?” the waitress asks.

I fully expect George to ask what we want to eat, but he doesn’t. He ignores all of us, Umma included, and begins ordering feverishly.

“We’ll get the chow mein, kung pao chicken, sweet and sour pork, and broccoli beef. Oh… and an order of fried rice. With shrimp. No spice.”

“But I like my food spicy,” Ji-hyun interjects. “And isn’t that too much food? It’s just the four of us.”

“No spicy,” Umma says. “George can’t eat spicy.”

Of course he can’t fucking eat spicy food.

The waitress finishes jotting our order down in her notebook. “Great,” she says. “Please let me know if you need anything else.”

“Xiexie,” George blurts. He puts his hands together and bows his head.

“Xiexie,” the waitress responds. She bows her head slightly and leaves.

He stares at the door for a full minute after she’s gone. “The service here is so great,” he says with a wistful sigh. “Wish all the restaurants were like this one.” He untangles himself from my mother. “Hold on. There’s something on your face—” He rubs the side of her nose with his index finger. “There.”

Ignoring Ji-hyun and me, the two of them launch into another nonsensical conversation. Despite the language barrier, George and Umma seem to be having a good time together, much to my disappointment. Ji-hyun keeps glancing at them, and though her hand is lying on the table, I see her fingers twitching. In her head, I know she’s scratching the shit out of her ankle.

The door slides open again and servers dressed in black and white enter, platters of rice and meat overflowing in their arms. George cranes his neck, staring out the door. He’s scouring the other room for our original waitress. Next to me, Ji-hyun clenches her fists.

We look at the mountains of food. It makes me anxious, the sheer amount that has arrived in front of us. George has given up on searching for the waitress and turns his attention back to the table, scooping piles of noodles and rice onto his plate. He doesn’t serve Umma or any of us first, like our father would have done. On the rare occasions we went to a restaurant, Appa would make sure that we had enough to eat before getting anything for himself.

Umma leans over and cuts George’s pork and chicken into little pieces. Ji-hyun takes an enormous gulp of jasmine tea. She hasn’t even looked at the food yet. I prod her under the table. She shakes her head so that only I can see. I want to ask her if everything is okay, but I also don’t want to draw attention to her.

The food is awful. It’s overly sweet and so salty that I worry about my mother’s blood pressure. Grimacing, I force it down with a sip of lukewarm water.

“Isn’t it great?” George says, his voice booming. “This is the best Chinese restaurant in the world!”

“It is?” I ask, scrunching my nose in disgust. “It doesn’t seem very authentic… there are some other places in the San Gabriel Valley that I think—”

“I’ve been to China. Have you?”

“N-no, but—”

“Trust me on this. I was in Shanghai for a month in 1987, and this restaurant is so much better than what they have over there. I swear on my mother’s life!”

Ji-hyun scowls. Swearing on your mother’s life is something so American, so white, that neither of us can truly understand it. In our culture, swearing on your mother’s life is probably one of the worst sins you can commit. What is there that’s more important than your mother, your father, or your grandparents? It doesn’t sound like George has ever heard of filial piety.

Even after an hour, there’s more food left over than we could possibly eat in a week. Umma scoops it into takeout containers and places them in plastic bags, tying the loops into neat little bows. “You take it,” she says to George. “Your dinner this week.” He nods enthusiastically and pays the check with a hundred-dollar bill that he slaps down onto the tablecloth. His wallet is flush with cash, the leather stretching around it. I don’t know if I’ve ever seen that amount of money in my life. It looks like a thousand dollars, maybe two. Umma glances at it before turning away, but it’s too late. I’ve already seen the hungry gleam in her eyes.

Outside, my mother clings to George, their hands crushed together. She doesn’t want him to go. She doesn’t want our time with him to end. The rain has cleared, just as she predicted, and though the sky is still cloudy, slices of blue and sunlight have broken through.

“It’s such a beautiful day,” Umma murmurs. “I don’t want it to go to waste. What if we went for a walk?”

Ji-hyun groans. “I don’t want to,” she says in an uncharacteristically childish whine. “Besides, everything is wet.”

“Oh, don’t be silly, JW,” George says. “If your mother wants to go for a walk, we should go for a walk.”

Ji-hyun glowers at him. “I’m Ji-hyun. Not Ji-won.”

“Right. Sorry, JH.”

We’re forced to follow behind them on the narrow sidewalk. Ji-hyun and I walk slowly, and the gap between us and them grows until the two of us are a quarter of a block behind them. Only then does my sister grab me, wrenching me backward.

“Hey!”

“What a jerk,” Ji-hyun hisses in my ear. “How do we get rid of this clown? I don’t ever want to see him again.”

“Can you stop? I don’t like him either, but at least you can wait until we get—”

“Wait for what? This is ridiculous!”

Ahead of us, Umma and George have come to a sudden stop. They turn and wave, motioning us to join them. George cups his hands around his mouth. “What’s going on, slowpokes?” he calls out. I pull free from Ji-hyun’s grasp and hurry forward. She continues to grumble behind me, walking at the same sluggish pace.

They’ve found an ice cream shop in a dilapidated strip mall. We step inside, the bell on the door tinkling above our heads. It’s as if we’re transported into an ice cream parlor from the eighties. The interior is outdated and old. The floor is covered in dark stains and deep gashes. There’s an unpleasant sour odor lingering in the air. George looks around. “They don’t make them like this anymore,” he says. “I miss the good ol’ days. Kids nowadays are too soft.”

Umma badgers me until I get a cone—“I won’t get anything unless you get something, and George won’t get anything unless I get something,” she says reproachfully—while Ji-hyun stands in the corner, haughty and unimpressed. George gets rum raisin, and Umma gets vanilla. I order mint chocolate chip.

“Hey, the sun is coming out!” George says, peering out the window. “Let’s eat our ice cream on that bench over there.”

Everything is still glistening, soaked in rain. Umma fusses about getting wet, but George frowns. “You girls are too high maintenance,” he complains. “It’s just a little water. It won’t hurt you.” He grabs Umma, tugging her down; she shrieks as she lands straight into an icy puddle in the middle of the bench. George cackles, and then he reaches for me, his hairy arm outstretched. I turn, but he’s too quick. His fingers wrap around the back of my arm, grazing my ribs. He pulls me down, the ice cream in my hand falling with a wet splat on the floor. Umma is talking, her voice high-pitched and upset, but all I can see and hear is George, his eyes straying down to my neck, to the softness of my chest.

For the first time, I notice that his eyes are blue: a pale, icy blue that reminds me of the Niagara Falls, where my father took us on vacation six years ago. I don’t know why I didn’t notice them before.

Excerpted from The Eyes Are the Best Part, copyright © 2023 by Monika Kim