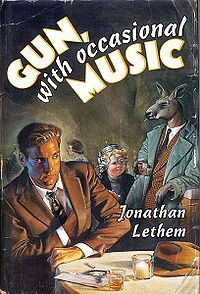

Jonathan Lethem’s debut novel (Topeka Bindery, 1994) has one of the best titles I’ve ever heard. It is everything a title should be—iconic, inventive, intriguing, thematic. I admit, I read the book for the title, not really expecting that it would live up.

It does. The book, too, is iconic, inventive, intriguing, thematic. On the face of it, Gun, with Occasional Music is a classic hard-boiled detective novel with a series of well-worn science fictional genre twists (anthropomorphic animals; totalitarian dystopia), but this particular novel manages to engage with its genre trappings while not being constrained by them.

It features a hard-boiled first person narrator (one Conrad Metcalf, private inquisitor, drug addict, and hobby metaphorist) attempting to solve the brutal murder of a former client. In the classic style of the P. Marlowes and Continental Ops he’s descended from, no one in Metcalf’s life can be trusted, and the forces of the underworld and law and order are both equally arrayed against him. He’s a Hammett/Chandleresque rusty knight, and in the end he makes no difference in the world at all—except maybe to find answers.

Metcalf may be a noir hero, but he moves through a Dickian setting of collapsible identity and compulsory drug use, where a totalitarian government has banned narrative—there are no words in newspapers, only photographs; radio news broadcasts are delivered via theme music; television is abstract; only the police (“Inquisitors”) may ask questions.

The police—and Metcalf. Because Metcalf is a former Inquisitor gone private, washed out of a corrupt system. He has a license to ask questions. For now.

In Metcalf’s world, evolved animals compete in the job market with humans and are exploited by them. Kittenish little girls are real, actual kittens. Immature, narcissistic adults are actual babies, evolved and abandoned by absentee parents. Metcalf’s unable to sustain a relationship because his ex-girlfriend took his balls—literally. Some people compartmentalize their lives into chunks with drugs, forgetting their work at home and their home at work.

If this seems like a world of concretized metaphor, that’s because it is. Which is where the real brilliance of the book lies, and that’s the thing that allows it to transcend its somewhat shopworn furnishings. Because it’s a narrative about a world that has outlawed narrative, and it deals chillingly with the consequences of denying the human mind the single most important tool that we use to construct reality and identity. We tell stories: stories are how we interact with our lovers, with our jobs, with our purposes in life, with our environment. It’s stories that allow us to compromise and to challenge, narratives that lead us to revolution or to agreement.

Remove the narrative, remove the power to ask questions or manipulate information, and you have—you have a world of sheep. Just waiting to be slaughtered.

And when you add to this a protagonist (or perhaps an antihero) whose purpose in life is questioning, is building narratives, whose chief joy seems to be creating elaborate, Chandleresque metaphorical flourishes—and commenting on them, in one of the great meta moments of modern literature—well, it takes a heck of a writer to pull that off.

The gun of the titular mantlepiece does not appear until the last act of the book, and it is exactly as advertised—a gun that plays ominous 1930s radio drama music whenever it is handled. It’s a striking metaphor in a book that is all about concretized metaphors, a kind of exclamation point cherry atop the thematic sundae of the novel.

Elizabeth Bear is a firm believer in the narrative utility of cat-girls.