Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

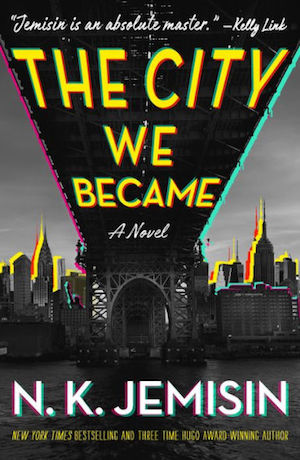

This week, we continue N.K. Jemisin’s The City We Became with Chapter 9: A Better New York Is in Sight. The novel was first published in March 2020. Spoilers ahead!

“People who say change is impossible are usually pretty happy with things just as they are.”

Chapter 9: A Better New York Is in Sight

The Art Center is intact when Bronca arrives for work. She starts by touring the galleries; it’s important “to keep art foremost in her routine, if not her mind.”

She heads to the newest exhibit: photographs of graffiti by an artist using material from spray paint to natural pigments. His subjects are strange: howling mouths, enormous eyes, a tranquil meadow with a ledge like a giant’s handhold. This artist is clearly “another of [Bronca], part of New York.” Maybe when “Bronx Unknown” opens, he’ll reveal himself.

A visitor is already examining the exhibit: a pale-skinned woman in a white pantsuit. She’s studying Bronca’s favorite piece: a young man sleeping on old newspapers. Powerful work, the woman says. It calls, “Come here. Find me. Unease ripples through Bronca: “Something in the bone knows its enemy.” Don’t underestimate the scrawny kids, she advises. Forced to fight constantly, they may grow up to fix the world.

The woman grins toothily at Bronca’s dig. She introduces herself: Dr. White, of the Better New York Foundation. She understands Bronca spoke yesterday with a “lovely group of young artists.” The Alt Artistes, whose work violated the Center’s policy against bigotry.

White shows Bronca a check for 23 million dollars, the Center’s for displaying just three Artiste pieces. The Center could run for years on that donation; Bronca’s tempted. Then White adds that the Center must also remove “Bronx Unknown.” No way in hell.

Out of habit, Bronca shakes White’s hand and feels a stabbing sensation; later she’ll find “tiny indentations” all over her palm. White seems to waver on her way out, her shadow contracting from vastness.

Raul, the Center’s board development chair, calls. The board wants to accept the Foundation’s offer. Bronca can concede or get fired. Hasn’t she seen the Alt Artistes’ latest video?

Yijing, Jess and Veneza fill Bronca in on the Artistes’ online harassment campaign, branding the Center discriminatory to white males. They’ve also doxxed Center staff contact info, triggering a deluge of threats. But Yijing and Veneza launch a social media counter-campaign that rallies support for the Center; by evening the tide’s turned. Raul tells Bronca that the board’s decided to reject the donation. No apology, but at least Bronca still has her job.

Bronca and Veneza stay overnight at the Center. A “nudge” from the city wakes Bronca to sounds of furtive activity below. She creeps downstairs, where something has “erased” part of the stairwell murals. A woman’s sobbing reaches her as if from a distance, a one-sided conversation with something that considers her a flawed “creation.”

On the ground floor, Bronca finds the photos of Bronx Unknown’s work piled on the floor, doused with lighter fluid. On top is her favorite, the boy’s face blacked out. Stall Woman’s voice mocks her. A section of wall peels open. The mass of whiteness that slips through morphs into a new Woman-in-White, model-perfect. Three Artistes block the gallery exit, including leader Manbun.

White shrugs off Bronca’s taunt that she has “trouble at home.” They both answer to boards. By her people’s standards, White’s “barely more than an infant, hopelessly unteachable.” By Bronca’s, she’s “ancient and unfathomable.” Still, she regrets what must be done.

At White’s gesture, the walls birth murals like the painting that sickened Bronca the day before. White repeats Stall Woman’s offer: She’ll spare Bronca and her “favorite individuals” from the “conflagration to come,” for a time. The Bronx, will be the last “enfolded.” All she must do is find the sleeping boy for White.

Buy the Book

Leech

Bronca’s steadied by the boy’s portrait, even defaced, and suddenly understands it. The city painted that mural for its unconscious avatar, who nearly destroyed himself fighting for it. He needs all five boroughs to heal him.

This isn’t the first time Bronca’s been threatened by those who would “invade her, infect her most quintessential self and leave only sanitized, deadened debris in their wake.” It’s just the first time she’s faced the threat as “the goddamn Bronx.”

Bolstered by avatar-knowledge, Bronca grows “expansive, mountainous … bolted to a million foundations,” her flesh “the soil where a thousand generations of [her] mothers grew and thrived.” Her mere toe-tap generates an energy wave that kills “every tendril of White” in the Center. The Artistes drop, strings cut. White makes a last effort to recruit Bronca, saying they’re both undervalued by their “betters,” but gets nowhere. White insists that New York threatens infinite dimensions. They’ll meet again, “the day that all masks are set aside.”

White and her tendrils vanish. Veneza stands at the gallery’s edge, and by her shocked expression she’s witnessed much of the craziness. Bronca reassures her, then calls the police to insist on pressing charges against these well-connected vandals. Soon after, three people show up at Bronca’s office.

Bronca recognizes them as “the missing fragments of her self… Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens,” grinning to have found her, their missing fragment.

This Week’s Metrics

The Degenerate Dutch: The Alt Artistes pull out every stereotype they can find in harassing the Center staff. Bronca has a PhD even though indigenous folks are “supposed to be poor,” and Jess’s Judaism proves “who’s really behind this.”

Libronomicon: The main city avatar, at least in his not-exactly-self-portrait, sleeps on a bed of old newspapers: Village Voices and Daily Newses, the New York Herald Tribune and the Staten Island Register. All the different versions of reality through which the city records and remembers itself.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Veneza assures Bronca that extradimensional horror won’t set her frothing at the mouth. (Apparently a real risk, along with self-inflicted eye removal. Ick.) “I’m from Jersey.”

Anne’s Commentary

Bronca, eldest of the boroughs, has been chosen as team librarian and lore master; the City’s gifted her knowledge collected about the Enemy over millennia, downloading the biggest textbook ever onto her cerebral Kindle. Unfortunately, she hasn’t gotten the latest edition. That’s not the City’s fault, since the update chapter has yet to be published. In fact, its rough draft is being written even as New York’s champions battle what seems to be a new phenomenon.

Taken as human, Dr. White would be bad enough in Bronca’s book. Towards the end of their encounter, however, White reveals her true nature. Her too-wide smile and too-prominent dentition have disturbed Bronca from the start, but her handshake is an actual shocker. Bronca tries to dismiss the jabbing pain it inflicts as her own problem, allergies or eczema or nascent shingles. She comes closest with allergies, given her body’s reacting to the biggest inimical substance ever, Otherworldliness embodied. When White steps out into sunlight, Bronca sees her waver like a “heat-haze flicker, a channel-change interstitial instant.” Her white hair turns honey blond, her fancy white heels yellow, and her shadow has to shrink to match her mass.

Wisely, Bronca checks her lexicon for an explanation of her visitor. She doesn’t find any mention that the Enemy can manifest as “a small rich passive-aggressive white woman.” Maybe she’s just being paranoid, “seeing danger under every extremely large check.”

Bronca is wise enough not to shrug off her suspicion entirely, but for a while Real Life Bullshit demands her attention. Real Life Bullshit is a weapon the Enemy can deploy to devastating effect via a small rich passive-aggressive white woman, as we saw in Chapter Eight, when it hit Brooklyn with a nuke-level eviction notice. Bronca’s hit with the ultimatum Surrender your principles or look for another job. To that pressure, add a social media attack campaign from the Alt Artistes, White’s human minions.

Distraction is a powerful tactic. Distraction might have driven Bronca to career—and existential—doom if not for all the people who have her back. Forget the Center’s board, which is on Team White. The Center’s staff and artists and supporters are solid Team Bronca. Team Bronca, too, are the sympathetic thousands who join via tweets, comments and blogs in Yijing and Veneza’s counter-campaign. Bronca finds their unexpected assistance “the most beautiful thing she’s ever seen.”

As the embodiment of the Bronx, Bronca is effectively a superhero, but she didn’t gain her superpowers via radioactive spider bite or genetic mutation. The Bronx in toto, people and infrastructure and history, is the source of her power, its collective energy the force she wields against the Enemy. Bronca always tries to remember that “the way of the Lenape is cooperation.” That “it’s a struggle sometimes” could be her fatal failing.

That the Woman in White attempts to make Staten Aislyn an ally isn’t surprising. Aislyn is young, repressed, pathologically lacking in self-confidence. Bronca’s pretty much her polar opposite. So why does the Woman spend so much time, first from the bathroom stall, then as “Dr. White,” trying to turn Bronca? As perhaps the most powerful borough-avatar, Bronca would be a prize ally, but wouldn’t that power also make her the most difficult to lure to the Other Side?

Not if Bronca’s personal and cultural “way” of appreciating and cultivating community can be overwhelmed by her hard-learned “ways” of independence, self-confidence, even protective insularity. Bronca has resisted seeking out the other borough-avatars even though she, the lexicon-holder, knows it’s essential. Which of the other boroughs has ever sided with the Bronx? Why should the Bronx side with them? It—and she—have problems enough of their own.

The Woman has already used Staten Island/Aislyn’s resentment and fear of the other boroughs to sway her. She wasn’t likely to miss the similar chink in Bronca’s armor. Of course, she’ll try pressuring Bronca with Real Life and eldritch menaces. Bronca won’t expect anything less. She’ll try taunting Bronca. Again, Bronca will expect this.

What Bronca may expect least is for the Woman to angle for her sympathy. All along the Woman has interspersed threats with expressions of understanding. On the night of the Center break-in, Bronca overhears the Woman sobbing to a Higher-Up about mistreatment. If there’s any situation Bronca can sympathize with, it’s that. Does she really “overhear” this one-sided conversation, or has the Woman staged it? I’d say the latter, but does that absolutely preclude the Woman from a fellowship of the underappreciated with Bronca?

After the gallery showdown, the Woman continues to stress how much she and Bronca have in common. Bronca is “unwilling to feel sympathy anymore,” but she acknowledges that the Woman’s parting nod shows genuine “respect” for the Bronx’s strength.

So, are they frenemies now? Hard to tell where one stands with Bronca sometimes—she even greets her avatar “kin” and “battle companions” with “What the shit do you want?”

Kinda gotta love her for that.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

The two core questions of horror are “What’s scary?” and “What should we do about it?” Ghosts are scary, and we should avoid ill-reputed houses. Ancient tomes of forbidden lore are scary, and we should read them anyway. Monsters are scary, and we should slay them—or become them, or learn to see the world inside-out from their perspective (which can also be scary).

One of the things I appreciate about The City We Became is the range of answers to that first question. Extradimensional horrors that want to destroy your newborn city: definitely scary. Extradimensional horrors that can collapse bridges with their tentacles: also scary. But then we give those horrors mycelial networks to spread through your city’s gestalt, effacing it and controlling its residents. On the flip side of the same coin, human bigots—already capable of evoking fear in their own right—make easy tools for those networks, adding destructive power to both. It’s a short leap from hating some of your fellow humans to existentially threatening the whole species.

What’s scarier, per Sao Paulo, is that these are new tricks. The Enemy has always been a threat, but one that fades away if the initial tentacle-flailing fails. Suddenly, for New York, the Enemy has become nuanced. Strategic. Empathetic—just enough to multiply its dangers a thousandfold.

By me, this is the scariest chapter so far. For those of us who aren’t actually city avatars or Call of Cthulhu investigators, giant tentacle monsters are not an immediate concern. Alt-right attention economy doxxers, on the other hand, are all-too-familiar. Give them brain-breaking art, and an eldritch angel investor (demon investor?) who can hook them up with the worst reality-warping excesses of late-stage capitalism, and Bronca’s in deep—and relatable—trouble.

Fighting tentacles is so much easier than fighting the logic of moneyed systems. If someone offers you enough, for a good enough cause, don’t you have an obligation to accept? Regardless of the cost? You could turn it down for yourself, but your family or organization or country has larger, more important needs. Isn’t refusing the bribe that could cover those needs selfish? How can you be so irresponsible as to have principles?

That’s scary.

But it’s in answering the second question that the chapter—and the book as a whole—really excels. Because what we do about the scary thing, in this case, is community organizing. Bronca and Brooklyn are much alike in this way. Both have created webs of human connection, and both draw on those webs for practical as well as supernatural protection. Assuming there’s a difference. City wakefulness, and city magic, draw from the same things that in purely ordinary terms make them live and thrive. And when all those things—all those people—come together to defend their community, it’s understandably “the most beautiful thing [Bronca’s] ever seen”

It’s telling what concessions the Woman in White tries to force on the Center. She could have left the Alt Artists out of things entirely: just offered a huge bribe to remove the art of the main city avatar. By itself, that seems worth her while: it is, literally, the art through which the city breathes. But she demands something to replace it, something that would spread her reality and pain Bronca every time she saw it, and that overreach is what pushes public outrage to the point where the Board has to backtrack. Strategic screw-up, or necessity? Is it enough to bleed the city, or do her goals require writing it over with something specific?

She hints at answers, a little. She’s ancient by our standards, young and hopelessly ignorant by her own species’s (assuming “species” is the right word). Or perhaps she’s a tool, her clever nuance a horror to her own creators. We hear her sobbing, begging them for approval. And we’ve also seen her tempted by what humanity has to offer, convinced that our destruction is sad but necessary. She claims to understand us—again, at least by the standards of her own people. When she’s not playing the villain, she’s talking about her similarities to the avatars: the desire to survive, the desire to be seen and valued as a separate entity, even the willingness to do the right thing at great cost.

She really would be sympathetic, if it weren’t for that whole necessary destruction thing.

Next week, we dive into Sonya Taaffe’s newest story (and doubtless get immersed in all manner of aquatic ephemera). Join us for “As the Tide Came Flowing In.” You can find it in her new collection of the same title.

Ruthanna Emrys’s A Half-Built Garden is now out! She is also the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.