Toph invented cops.

I have to reiterate that, because it’s a fact. Toph Beifong invented the first and only police system in the Avatar universe, and it’s deeply insidious and bizarre.

We have to examine, first of all, how the police force in Republic City came about, and why Toph was the worst and only person who could have created it; and secondly, why writers of speculative media choose to create endings for characters with great power that continually place them in systemic positions of power over other people.

Before Republic City there were no cops. There were systems of power and groups of people who had taken power, but ultimately the kind of force that internally polices its own people did not exist in the original Last Airbender series. Toph Beifong invented a system of policing that placed exclusive members of the metalbending caste in a position to enact and enforce rules, regulations, and laws within a single community. There are examples of proto-police forces in the original series, but Toph is ultimately responsible for establishing and inventing the police system we see in The Legend of Korra.

Two notable examples of the proto-police force in Avatar are the Kyoshi Warriors and the Dai Lee, both of which share another Earthbending founder—Avatar Kyoshi. The Kyoshi Warriors are armored non-benders who protect their town and island from intruders. They are not a police force, at best they are a local cultural militia, which serves the greater Earth Kingdom people. In later episodes, Suki and other warriors are shown to be in service to the Kingdom itself, aiding refugees at the Serpent’s Pass. The Kyoshi Warriors are the ones who save Appa, after all, and they make it their duty to protect him. All of this was done while acting as Kyoshi Warriors, in full makeup, armor, and silks. They remained Kyoshi Warriors even while they were away from Kyoshi Island. Their service did not stop with their island, but fanned outwards.

The Dai Lee are more complicated. It’s been revealed in the canonical online game Escape from the Spirit World that Kyoshi established the Dai Lee as a kind of praetorian guard to protect the Earth King, and, by extension, the cultural legacy of Ba Sing Se. These elite earthbenders became the shadow government. Whoever was the head of the Dai Lee was, by extension, the head of the Kingdom. The policing came not from a desire to enforce laws or enact justice, but from a dictatorial position of totalitarian power. Police need to (theoretically) serve the people, and the Dai Lee, while oppressive, were instead controlling them and never attempted to position themselves in service to the populace. Going further, the Dai Lee eventually betray their Kingdom and join Azula, cementing their position as a security team, and not a police force.

Toph came into contact with both of these groups during the formative years of her childhood as she was watching the way that powerful people exist and maintain their power in the world. When Republic City was founded, the people at the core of it decided on laws and ideals. Toph stepped up and said that she would enforce those laws, and, according to The Legend of Korra—The Art of the Animated Series, Book One: Air, Toph became the Chief of Police of Republic City and founded the elite Metalbending Police Force.

She took the ethos (and, it must be noted, the aesthetics) of both the Kyoshi Warriors and the Dai Lee and transformed them into a system of policing that takes elite metal benders and creates a community separate from the populace, gives them a recognizable uniform, trains them to use their bending in specific and non-contestable ways, puts them in armor, and then allows them to make subjective determinations of justice at will in Republic City. Toph took the armor of the Kyoshi Warriors and the color palette of the Dai Lee to create the Metalbender Force uniforms. Much like the Dai Lee were portrayed to be the only group that used Earth-hands as a specific bending technique, the Metalbender Force also utilizes a kind of bending that is so specific because it was literally invented by Toph. This means that, until Toph’s daughter Suyin taught her community, Zaofu, metalbending, the Metalbending force had exclusive use of a powerful, dangerous, and non-combatable weapon.

While the police of Republic City are at the whims of the people (more or less), but they are not in service to the community like the Kyoshi Warriors, nor are they puppet masters taking over the decision-making of the city. They are a force that is weaponized against the community, against Avatar Korra, and against the other protagonists of the series.

So why did Toph, a young woman who had lived her whole life bucking rules, systems of control, and expectations, suddenly have a change of heart and become “The Man?” Ignoring writer’s decisions, we can see that Toph was traumatized by the systems of control she saw weaponized against her in her childhood in order to subdue her and keep her obedient, and then replicated those same systems when given the opportunity. Her parents sought to control her, and when she couldn’t be controlled, they sought to imprison her. When she presented reasonable arguments she was shut down and belittled, and later, chased all over the earth by bounty hunters. To Toph, this is what unreasonable use of power looks like. Why would she then think that this same method of policing is a good use of her own power? Why would she think that in order to create order she needed to become the person she hated most as a child?

Toph was caught in a cycle of abuse, and in order to take control of her own, personal power, and maintain that control, she created a system where she could demand obedience from others. It makes little sense that Toph, who flaunted rules and social norms at best, and outright broke laws throughout her life, would choose to perpetuate this cycle. It’s even shown that when she raises her children she maintains a hands-off policy, and allows them to make their own rules. This fails, of course, because Toph is not a good mother, but it proves again that rules are not in Toph’s character. Following rules, creating them, enforcing them, those are not things that give Toph joy. Toph breaks rules. She always has. So why on earth did she lead a police force? It’s a baffling and unceremonious addition to her story, considering it’s already happened by the time Korra begins, and it only serves to weaken who she is as a character.

Toph is simultaneously the worst person to found a police force, and the only person who could have done it, considering what police stand for in our current, modern society. She is obsessed with her own power, constantly saying that she’s the best Earthbender in the world, that nobody can beat her, and that she’s more powerful than any bender, including Korra. She’s also judgemental, often berating Katara for acting motherly or asking for help, and later, Toph talks down to Korra during their interactions, dismissing her and keeping her at arm’s length. Toph is also incredibly independent, and uses her power against those who defy her without asking questions. She’s not really a team player, and more than that, she’s not one to defer authority. Unlike the other members of the Gaang, Toph is someone who enjoys proving that she’s better than other people, as shown by her behavior in the wrestling bending ring, and rarely humbles herself. None of these things make up the personality of someone who should be given power over a judiciary police force. It’s strange that Toph was given this kind of power, that this was the way power was distributed in the first place.

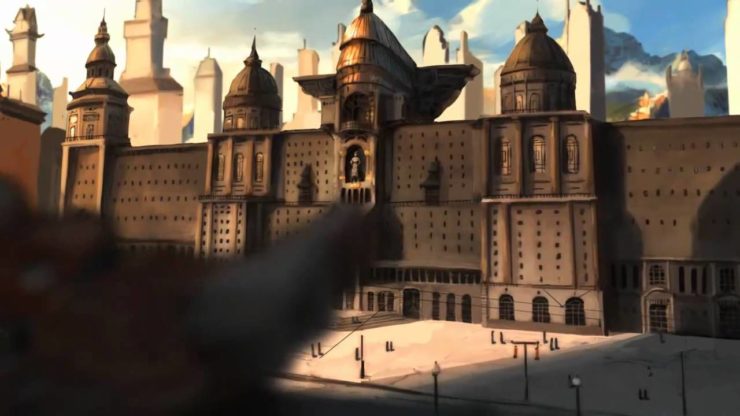

A “good” police force requires lowering yourself to the same level as everyone else, and in Republic City, this means non-benders. From inception, Toph’s police force was doomed to fail because she had created an environment of superiority. Toph and the police were set up for failure from the beginning; there was no way that she would be able to lower herself to service. This isn’t even something that she doesn’t know about herself, and the choice to have Toph ignore her own flaws to the extent that she literally invents modern, corrupt policing, unchecked, makes her seem like a tyrant. She’s always wanted people to know that she’s better than them, but in Korra it feels like the writers literally wanted to turn her into an Emperor, undermining her growth throughout Last Airbender entirely. You only have to look at the palace that is the Republic City police station.

Much like Kyoshi, Toph is a bend-first, examine later person. Kyoshi is brutal and swift. She makes a decision and she sticks to it. She does not feel remorse for killing others if she feels that it’s justified. Much like Kyoshi, Toph believes that the ends justify the means, and is unapologetically violent and brutal when something stands in her way.

Becoming a cop means that you need to make immediate decisions that affect lives without questioning your own motives—you are there to enact the law, not examine it.

Regardless of where Toph ends up in the Korra series, we must criticise the decision to have her create a hierarchy where she and her daughters rise through systems of power as a “city taskforce.” She creates a mode of policing that puts the community members in danger, and does not serve it. When her child was caught in gang activity instead of actively trying to solve the root of the problem, or trying to create a better city for her children, she decided to flaunt the very rules she was supposed to keep, tearing up Suyin’s arrest papers and sending her away. Much like when Toph forges refugee papers in Last Airbender and when she and Katara bluff their way into a party, she never quite learns to follow the rules. So why did the authors decide to put someone who hates rules in charge of enforcing them? Why was Toph’s power tamed through the replication of systemic oppression?

Powerful women are dangerous. Women like Toph (and, by extension, Katara) who are given extreme amounts of control over their own lives are brought to heel in narratives again and again. For Katara, this means giving her a family to look after, and reducing her to a kindly old grandmother in Legend of Korra. But for Toph, who was twelve years old and one of the most talented Earthbenders in the world, who left her family, who ran away to face down the tyrant Ozai, what could the writers do to show that she was able to keep hold of her power as a grown up?

She established the police. She created an acceptable way of utilizing her power against others that would be justified through the narrative. The message here is clear. After your adventure, after your return through the looking glass, the police are how you stay powerful. When you grow up, when you’re an adult, becoming a cop is how you maintain a clear and direct hold over your personal power and how you justify your power over others.

This is where a deeply flawed pattern comes to bear. As the writers created an ‘ending’ for a young girl, they chose to replicate flawed systems of control instead of reimagining a new system of equitable power and community. By teaching kids that cops are arbiters of “good power,” that this use of force is acceptable power, it exposes the ways that we think about power as adults. Kids becoming cops is not the end of their story. Kids joining the police force as a way to retain the power they had as children is not a hopeful ending, but an insidious one. Very few pieces of media that show intrinsically powerful ‘chosen one’ narratives have made any attempt to remove a continuity of power from careers in the police or the military, because becoming a cop is what heroes do. It’s an attainable form of hero-making in the real world. It’s complete propaganda.

This is a pattern, and it should be deeply criticized and examined. Two more examples of this come from the lesser-known Treasure Planet, where Jim Hawkins, whose story opens with two robo-cops dropping him off at home. Treasure Planet ends with Jim being escorted by those same cops, this time acting as an entourage when he returns from his year at the Military Academy. The larger example, and far more malignant, is Harry Potter. After spending his childhood years fighting against authority and bucking systems of control, destiny, and other people’s expectations, he turns around and becomes an Auror—a magic cop.

Toph’s journey doesn’t end with her founding the police force, but it does end with her running away from it. In order to interact with society in a socially acceptable way she had to be a part of the force. As soon as she retired, she exiled herself, a release from the hierarchy she created, but not releasing the city from the tyranny of her police. Lin does this as well, and while neither woman engages in the self reflection needed to see that police are a mistake, it’s obvious that both women value their control over the system over its service to the people. This, again, makes the police force a strange choice for Toph, as she is willing to decenter herself in Last Airbender when she vouches for Zuko to enter the group. She’s not afraid of radical change, so why does she reject change so thoroughly in Korra?

There is no space in a police state for power that remains outside of the systems of control. While Toph, for a time, benefited from the position of power within the system of oppression she created, she inevitably found it untenable. Police forces and systems are breaking down, in and out of fiction, and Toph was the only person who could have created the Republic City police force. By the same token, she’s the only one who can destroy it, but she chose to let it fester, and lead to the rise of the Earthbender antagonist Kuvira.

The police state in Avatar enabled villains, but the narrative didn’t go far enough vilifying the police state in its fiction. It’s time for the audience and writers to reject kiddie copaganda, and critically examine it throughout the stories children watch and the ones we watched as children. In speculative fiction, it’s even more important. Avatar is westernized anime, but at its heart, it’s a show about defining your own path and telling your own story. Powerful children deserve better, and we deserve to read narratives that reject the police force as one of the few structures that allow children to maintain power as they become adults.

Linda H. Codega is an avid reader, writer, and fan. They specialize in media critique and fandom and they are also a short story author and game designer. Inspired by magical realism, comic books, the silver screen, and social activism, their writing reflects an innate curiosity and a deep caring and investment in media, fandom, and the intersection of social justice and pop culture. Find them on twitter @_linfinn.