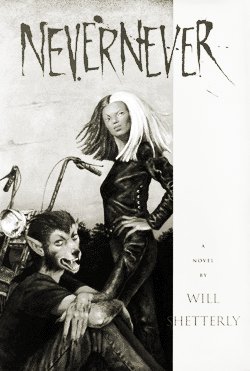

Welcome back to the Bordertown reread. The topic of today’s post is one of my favorite volumes in the series, the second of Will Shetterly’s Bordertown novels, Nevernever. As the copyright page points out, certain parts of this novel appeared in substantially different form as “Danceland” in Bordertown and as “Nevernever” in Life on the Border. So even if this is your first time through the books, if you’re reading them in order of publication, you’ve seen bits and pieces of this story before.

“Substantially different form” is correct important parts of the events described in the two shorter works are completely new in Nevernever. Even when they remain faithful to their earlier incarnations, you see the story from a different perspective, and that idea—that even when you think you know how a story is told, that you know the ending and how to get there, sometimes there are pieces of the story that you haven’t quite seen—is an important one here. And if you’re rereading, like I am, part of that experience is almost always made up of noticing things for the first time. Stories change and make themselves different, depending on who you are when you read them.

Pieces of the Elves versus Humans conflict that I noticed in Life on the Border carry over here in Nevernever, but they do so in a more nuanced fashion. Nevernever doesn’t deploy the easy shorthand that the humans and halfies are good, and the Elves are the bigots and the bad guys. Cristaviel, one of the Elven characters, speaks of the events of the story as part of a struggle between Faerie and the World, but the conflict in these pages isn’t quite as simple as that. It’s really about the relationship between factions in each place, about whether doors and borders ought to be open or closed. It’s about the question that precedes that debate: whether minds ought to be open or closed.

It’s a question that comes up anywhere there is a border, since that word implies sides, and that implication leads to the question of who belongs on which one. It’s a testament to Shetterly’s handling of the theme that the answer to that question in Nevernever requires the characters to ask themselves who they are, not just what they are, or where they were from before they wound up in Bordertown.

Answering that question requires some of the characters—specifically Wolfboy, Florida, and Leda—to spend time outside of Bordertown, in the wilds of the Nevernever. The Nevernever is a pocket of strangeness on the edge—or perhaps the border—of an already strange place. It’s a wild place, and going into the woods here serves the same function that it does in any fairy story: the woods are where you find out who you really are. It’s a nice reminder that no matter where you begin, there is always a place that can take you far enough outside the known that you can see the truth.

Neverwhere also serves as an elegant ending to a particular chapter of Wolfboy’s story. In Elsewhere, when his wish that people would see him, and know how special he is, was made flesh in his transformation to Wolfboy, he remarks on the need to be careful what you wish for. Here, he gets to wish to be what he is, and the choice he makes illustrates how much he has grown into his true self, regardless of the shape that self wears.

Shetterly wraps all of this around a mystery, a murder, a lost heir of the Elflands, and the usual terrible beauty of growing up, and becoming, well, becoming anything really. Isn’t that what we do, when we’re growing up? And in rereading, and rethinking about the books in this series, I’ve come to realize that one of the biggest things I love about them is they are about becoming. The biggest magic in Bordertown is that it’s a place to Become. Unencumbered by rules or expectations beyond your own, this is a place where you can choose who you are. That’s the kind of magic that’s worth crossing a border, or journeying into a place far more strange, to find.

Kat Howard’s short fiction has been published in a variety of venues. You can find her on Twitter, at her blog, and, after June 1, at Fantasy-matters.com. She still wants to live in Bordertown.