The year is 500 AD. Sisters Isla and Blue live in the shadows of the Ghost City, the abandoned ruins of the once-glorious mile-wide Roman settlement Londinium on the bank of the River Thames.

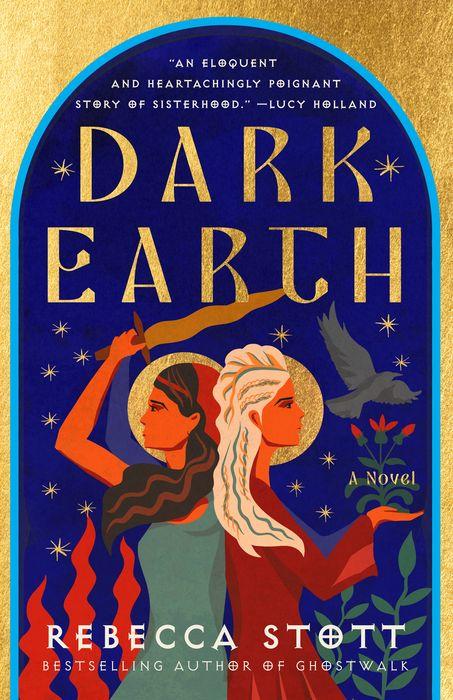

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from Dark Earth by Rebecca Stott, out from Random House on July 19th.

The year is 500 AD. Sisters Isla and Blue live in the shadows of the Ghost City, the abandoned ruins of the once-glorious mile-wide Roman settlement Londinium on the bank of the River Thames. But the small island they call home is also a place of exile for Isla, Blue, and their father, a legendary blacksmith accused of using dark magic to make his firetongue swords—formidable blades that cannot be broken—and cast out from the community. When he dies suddenly, the sisters find themselves facing enslavement by the local warlord and his cruel, power-hungry son. Their only option is to escape to the Ghost City, where they discover an underworld of rebel women living secretly amid the ruins. But if Isla and Blue are to survive the men who hunt them, and protect their new community, they will need to use all their skill and ingenuity—as well as the magic of their foremothers—to fight back.

An island in the Thames, c. A.D. 500

Isla and Blue are sitting on the mound watching the river creep up on the wrecks and over the black stubs of the old jetties out on the mudflats, waiting for Father to finish his work in the forge. Along the far riverbank, the Ghost City, the great line of its long-abandoned river wall, its crumbling gates and towers, is making its upside-down face in the river again.

“Something’s coming, sister,” Blue says. “Look.”

Buy the Book

Dark Earth

Isla looks. The wind has picked up. It scatters the birds wading on the mudflats. It catches at the creepers that grow along the Ghost City wall. It lifts and rustles them like feathers.

“Could be rain,” Isla says. “The wind’s turned.”

It’s late spring. There has been no rain for weeks. No clouds, just the baking, glaring forge fire of the sun. At first, after the long winter, the sisters had welcomed the sun coming in so hot. Dull roots had stirred. Flowers came early: first the primroses and bluebells in the wood, then the tiny spears of the cuckoo pint and the blackthorn blossom in the hedgerows. The bean seedlings had pushed up through the soil in their garden, fingers unfurling into sails.

Now the reeds whisper like old bones. The sisters swim in the river when they can steal away from the field or from Father’s forge. Around them the sun beats down on the mudflats. Meat turns. Flies gather.

Every evening the sisters climb the mound to watch for the sails of Seax boats coming upriver from the sea, the sails of the great wandering tribes, from the Old Country and the Drowned Lands of their ancestors, all heading west to find new land to farm. Some months there are no boats at all. Other months there are four or five, sailing alone or in clusters. Blue gauges a notch into the doorpost for each new sail she sees.

“The river is a firetongued sword tonight,” Blue says. She is making a necklace from the cowslips and the violets she’s picked, lost in that half-dreaming mood that takes her sometimes.

Isla looks. Blue is right. Between their island and the walls of the Ghost City on the far riverbank, the river runs between the mudflats in puckered silvers and golds, blues and reds, just like the swords that Father makes.

“What did the Sun Kings know?” Isla says, gazing over the river to the ruins beyond. “What happened to make them all go and leave their city like that? Was it the Great Sickness, do you think? Or worse?”

“What’s worse than the Great Sickness?” Blue says, holding the necklace up to the setting sun, humming a tune Mother used to sing in the Old Times.

Blue sometimes talks in riddles. She asks questions Isla can’t answer. Sometimes Isla tries. Usually, she doesn’t.

“Did they mean to come back?” Isla says. “Did something happen to them to stop them from coming back?”

Isla has been thinking about these questions for always and forever. The whole Ghost City is a riddle to her.

“Perhaps the marsh spirits chased them away,” Blue says, pulling down the skin beneath her eyes and baring her teeth, “or perhaps the Strix turned them all into crows.”

But Isla knows her sister doesn’t know any more about where or why the Sun Kings went than she does.

“We don’t know,” she says. “No one knows. We’ll never know.”

And then, with a sigh, Blue puts down her flowers and says, her eyes wide:

“Mother said there were gardens inside and pools of hot water and temples as big as ten mead halls and fountains full of coins and men who fought with bears and giants and—”

“Stop your nonsense,” Isla says, but she isn’t really listening. She is thinking that Father is late finishing his work, and that the food will spoil. She is wondering whether he has finally finished twisting the iron rods as she asked him to, so that she can start working on the blade tomorrow. Most nights he is out through the forge door long before they can see the first stars. He’ll be putting his tools away, she tells herself. He’s just taking his time.

“Mother told me,” Blue says again, her eyes closed, drawing shapes in the air with her long fingers. “She did. She said. She knew.”

Blue makes Isla wild sometimes with the things she says.

“You’re making it up,” Isla tells her. “Mother didn’t say any such thing. Anyway, how would she know? The Sun Kings left a hundred winters ago. The Ghost City is empty. There’s nothing living in there now except kites and crows. It’s all just mud and broken stone.”

“And ghosts,” Blue says, “and the Strix.”

Isla gives up. Blue’s face is flushed. She’s been sitting in the sun too long. Father says Blue is touched. Isla sometimes wonders if there is something wrong with her sister that often she seems to know what Isla is going to say before she says it, or she sees things others can’t see. Fanciful, Mother used to say. Your sister’s just fanciful, Isla. You mustn’t mind her.

“You’ve listened to too many of Old Sive’s stories,” Isla says. She can’t help herself. She is cross and hot and tired and the old darkness is gathering down inside her. It’s making her want to run again.

Wrak, the crow that Blue has raised from a chick, calls out to her sister from the thatch of the forge, then lands on her shoulder in a flurry of black feathers. Wrak. Wrak. Though she would never say it to her sister, Isla wishes Wrak would fly off to join his kin, the crows roosting in the Ghost City. He is dirty, full of fleas and ticks. Always looking for scraps. Stealing food. Up to no good. The way he looks at Isla sometimes, his head cocked to one side, his eyes shiny black like charcoal, that tuft of white feathers under his beak. It makes her skin crawl. But Wrak doesn’t go. He stays.

“Hush, we’re your kin now,” Blue says to him when she sees him gazing up at the birds flying overhead. “Hush, hush. Ya. We’re your kin.” She cradles his dirty oily feathers in her long fingers as if he is a child.

Blue has secrets. At low tide on the night of each new moon, she takes the path down through the wood to the promontory on the south side of the island, where she keeps her fish traps. She tells Father she’s checking the traps, but Isla knows she’s gone to speak to the mud woman. When the tide falls down there, the woman’s bones make a five-pointed star in the mud, her ankles and wrists fastened to four stakes with rusted iron cuffs, her bones white, the remains of her ribs the upturned hull of a boat. Curlews wade between her thighs.

Isla went only once. She won’t go again. She doesn’t want to look at that open jaw a second time, the black holes of the woman’s eye sockets.

Blue says that when the moon is full, the mud woman whispers.

“She’s dead,” Isla says. “Bones can’t whisper. They drowned that poor woman hundreds of years ago. Stop making things up.”

“Sometimes on the new moon,” Blue says, “she roars and swears to kill the men who pegged her. She pulls at her straps.”

“Enough. Enough of all that. Stop it. Just say nothing.” “But sometimes,” Blue says, “she just calls for her mother.”

When Isla had once asked Father about the bones, he’d said the elders of the mud woman’s tribe must have staked her out to teach the rest of her people to hold their tongues and do what they were told. He said they’d made a scapegoat of her. They’d done that back in the Old Country too, he said.

“Poor creature,” he’d said.

“What’s a scapegoat?” Isla had asked.

“You put all the bad luck in the village into one goat and then you drive it away,” he said. “Or you kill it.”

“Are we scapegoats?” Blue said.

“Not yet,” Father had answered. “Not if I can help it.”

The lights on the river have started to bleed in the dusk. Isla can’t see one thing from another out there. When she sits down next to her sister again, Blue drapes her necklace of flowers between the pair of brooches that Isla wears in the crook of each of her shoulders. When she’s got the flowers where she wants them, Blue puts her fingers on Isla’s eyelids and closes her own. She seems to be praying. She kisses each of her sister’s eyelids in turn, and then each of her brooches. Isla can’t tell if she is playing some new game or just being Blue.

All at once the crows scatter up and over the Ghost City, pouring up like the ashes from a great fire into the night sky, across the first evening stars, across the sliver of the new moon, roiling this way and that, making a great scattery and flinty noise with their beaks, and then roiling together all over again.

Isla starts to run. Across the yard, round the goat pen, and then she is pushing hard against the door of the forge. Inside, the room is dark. The fire has shrunk back to embers. Shadows from the guttering candle dance on the walls. And there is Father’s body on the floor, all crumpled, his hammer still clenched in his hand, his face twisted on one side, his mouth open like he’s trying to say something. And when she looks up, Blue is standing there in the doorway, quiet as anything.

Excerpted from Dark Earth, copyright © 2022 by Rebecca Stott.