Something is stirring in London’s dark, stamping out its territory in brickdust and blood.

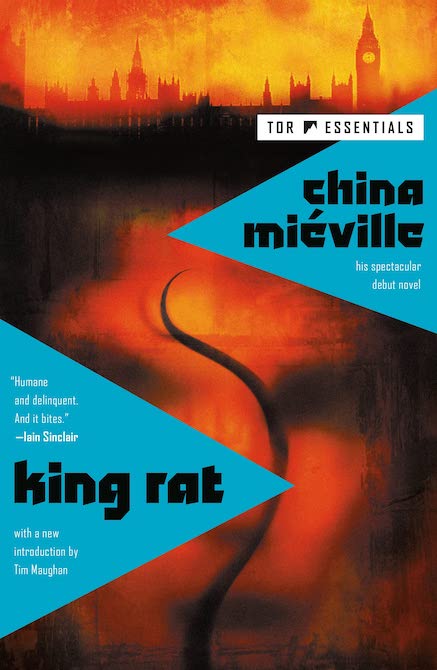

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from King Rat by China Miéville, which has a shiny new Tor Essentials paperback edition coming out on April 4th.

Something is stirring in London’s dark, stamping out its territory in brickdust and blood. Something has murdered Saul Garamond’s father, and left Saul to pay for the crime.

But a shadow from the urban waste breaks into Saul’s prison cell and leads him to freedom: a shadow called King Rat. King Rat reveals to Saul his own royal heritage, a heritage that opens a new world for him, the world below London’s streets.

With drum-and-bass pounding the backstreets, Saul must confront the forces that would use him, the ones that would destroy him, and those that have shaped his own bizarre identity.

Once, when he was three, Saul was sitting on his father’s shoulders, coming home from the park. They had passed a group of workmen repairing a road, and Saul had tangled his hands in his father’s hair and leaned over and gazed at the bubbling pot of tar his father pointed out: the pot heating on the van, and the big metal stick they used to stir it. His nose was filled with the thick smell of tar, and as Saul gazed into the simmering glop he remembered the witch’s cauldron in Hansel and Gretel and he was seized with the sudden terror that he would fall into the tar and be cooked alive. And Saul had squirmed backwards and his father had stopped and asked him what was the matter. When he understood he had taken Saul off his shoulders and walked with him over to the workmen, who had leaned on their shovels and grinned quizzically at the anxious child. Saul’s father had leaned down and whispered encouragement into his ear, and Saul had asked the men what the tar was. The men had told him about how they would spread it thin and put it on the road, and they had stirred it for him as his father held him. He did not fall in. And he was still afraid, but not as much as he had been, and he knew why his father had made him find out about the tar, and he had been brave.

Buy the Book

King Rat

A mug of milky tea coagulated slowly in front of him. A bored-looking constable stood by the door of the bare room. A rhythmic metallic wheeze issued from the tape-recorder on the table. Crowley sat opposite him, his arms folded, his face impassive.

“Tell me about your father.”

Saul’s father had been racked with a desperate embarrassment whenever his son came home with girls. It was very important to him that he should not seem distant or old-fashioned, and in a ghastly miscalculation he had tried to put Saul’s guests at their ease. He was terrified that he would say the wrong thing. The struggle not to bolt for his own room stiffened him. He would stand uneasily in the doorway, a grim smile clamped to his face, his voice firm and serious as he asked the terrified fifteen-year-olds what they were doing at school and whether they enjoyed it. Saul would gaze at his father and will him to leave. He would stare furiously at the floor as his father stolidly discussed the weather and GCSE English.

“I’ve heard that sometimes you argued. Is that true, Saul? Tell me about that.”

When Saul was ten, the time he liked most was in the mornings. Saul’s father left for work on the railways early, and Saul had half an hour to himself in the flat. He would wander around and stare at the titles of the books his father left lying on all the surfaces: books about money and politics and history. His father would always pay close attention to what Saul was doing in history at school, asking what the teachers had said. He would lean over his chair, urging Saul not to believe everything his history teacher told him. He would thrust books at his son, stare at them, become distracted, take them back, flick through the pages, murmur that Saul was perhaps too young. He would ask his son what he thought about the issues they discussed. He took Saul’s opinions very seriously. Sometimes these discussions bored Saul. More often they made him feel uneasy at the sudden welter of ideas, but inspired.

“Did your father ever make you feel guilty, Saul?”

Something had been poisoned between the two of them when Saul was about sixteen. He had been sure this was an awkwardness that would pass, but once it had taken root the bitterness would not go. Saul’s father forgot how to talk to him. He had nothing more to teach and nothing more to say. Saul was angry with his father’s disappointment. His father was disappointed at his laziness and his lack of political fervor. Saul could not make his father feel at ease, and his father was disappointed at that. Saul had stopped going on the marches and the demonstrations, and his father had stopped asking him. Every once in a while there would be an argument. Doors would slam. More usually there was nothing.

Saul’s father was bad at accepting presents. He never took women to the flat when his son was there. Once when the twelve-year-old Saul was being bullied, his father came into the school unannounced and harangued the teachers, to Saul’s profound embarrassment.

“Do you miss your mother, Saul? Are you sorry you never knew her?”

Saul’s father was a short man with powerful shoulders and a body like a thick pillar. He had thinning gray hair and gray eyes.

The previous Christmas he had given Saul a book by Lenin. Saul’s friends had laughed at how little the aging man knew his son, but Saul had not felt any scorn—only loss. He understood what his father was trying to offer him.

His father was trying to resolve a paradox. He was trying to make sense of his bright, educated son letting life come to him rather than wresting what he wanted from it. He understood only that his son was dissatisfied. That much was true. In Saul’s teenage years he had been a living cliché, sulky and adrift in ennui. To his father this could only mean that Saul was paralyzed in the face of a terrifying and vast future, the whole of his life, the whole of the world. Saul had emerged, passed twenty unscathed, but his father and he would never really be able to talk together again.

That Christmas, Saul had sat on his bed and turned the little book over and over in his hands. It was a leather-bound edition illustrated with stark woodcuts of toiling workers, a beautiful little commodity. What Is To Be Done? demanded the title. What is to be done with you, Saul?

He read the book. He read Lenin’s exhortations that the future must be grasped, struggled for, molded, and he knew that his father was trying to explain the world to him, trying to help him. His father wanted to be his vanguard. What paralyzes is fear, his father believed, and what makes fear is ignorance. When we learn, we no longer fear. This is tar, and this is what it does, and this is the world, and this is what it does, and this is what we can do to it.

There was a long time of gentle questions and monosyllabic answers. Almost imperceptibly, the pace of the interrogation built up. I was out of London, Saul tried to explain, I was camping. I got in late, about eleven, I went straight to bed, I didn’t see Dad.

Crowley was insistent. He ignored Saul’s plaintive evasions. He grew gradually more aggressive. He asked Saul about the previous night.

Crowley relentlessly reconstructed Saul’s route home. Saul felt as if he had been slapped. He was curt, struggling to control the adrenaline which rushed through him. Crowley piled meat on the skeletal answers Saul offered him, threading through Willesden with such detail that Saul once more stalked its dark streets.

“What did you do when you saw your father?” Crowley asked.

I did not see my father, Saul wanted to say, he died without me seeing him, but instead he heard himself whine something inaudible like a petulant child.

“Did he make you angry when you found him waiting for you?” Crowley said, and Saul felt fear spread through him from the groin outward. He shook his head.

“Did he make you angry, Saul? Did you argue?”

“I didn’t see him!”

“Did you fight, Saul?” A shaken head, no. “Did you fight?” No. “Did you?”

Crowley waited a long time for an answer. Eventually he pursed his lips and scribbled something in a notebook. He looked up and met Saul’s eyes, dared him to speak.

“I didn’t see him! I don’t know what you want… I wasn’t there!” Saul was afraid. When, he begged to know, would they let him go? But Crowley would not say.

Crowley and the constable led him back to the cell. There would be further interviews, they warned him. They offered him food which, in a fit of righteous petulance, he refused. He did not know if he was hungry. He felt as if he had forgotten how to tell.

“I want to make a phone call!” Saul called as the men’s footsteps died away, but they did not return and he did not shout again.

Saul lay on the bench and covered his eyes.

He was acutely aware of every sound. He could hear the tattoo of feet in the corridor long before they passed his door. Muffled conversations of men and women welled up and died as they walked by; laughter sounded suddenly from another part of the building; cars were moving some way off, their mutterings filtered by trees and walls.

For a long time Saul lay listening. Was he allowed a phone call? he wondered. Who would he call? Was he under arrest? But these thoughts seemed to take up very little of his mind. For the most part he just lay and listened.

A long time passed.

Saul opened his eyes with a start. For a moment he was uncertain what had happened.

The sounds were changing.

The depth seemed to be bleeding out of all the noises in the world.

Saul could still make out everything he had heard before, but it was ebbing away into two dimensions. The change was swift and inexorable. Like the curious echoes of shrieks which fill swimming pools, the sounds were clear and audible, but empty.

Saul sat up. A loud scratching startled him: the noise of his chest against the rough blanket. He could hear the thump of his heart. The sounds of his body were as full as ever, unaffected by the strange sonic vampirism. They seemed unnaturally clear. Saul felt like a cut-out pasted ineptly onto the world. He moved his head slowly from side to side, touched his ears.

A faint patter of boots sounded in the corridor, wan and ineffectual. A policeman walked past the cell, his steps unconvincing. Saul stood tentatively and looked up at the ceiling. The network of cracks and lines in the paint seemed to shift uneasily, the shadows moving imperceptibly, as if a faint light were being moved about the room.

Saul’s breath came fast and shallow. The air felt stretched out taut and tasted of dust.

Saul moved, reeled, made dizzy by the cacophony of his own body.

Above the stripped-down murmurings, slow footsteps became audible. Like the sounds Saul made, these steps cut through the surrounding whispers effortlessly, deliberately. Other steps passed them hurriedly in both directions, but the pace of these feet did not change. They moved steadily toward his door. Saul could feel vibrations in the desiccated air.

Without thought, he backed into a corner of the room and stared at the door. The feet stopped. Saul heard no key in his lock, but the handle turned and the door swung open.

The motion seemed to take a long long time, the door fighting its way through air suddenly glutinous. The complaints of the hinges, emaciated with malaise, stretched out long after the door had stopped moving.

The light in the corridor was bright. Saul could not make out the figure who stepped into his cell and gently closed the door.

The figure stood motionless, regarding Saul.

The light in the cell performed only a rudimentary job on the man.

Like moonlight it sketched out nothing but an edge. Two eyes full of dark, a sharp nose and pinched mouth.

Shadows were draped over the face like cobwebs. He was tall but not very tall; his shoulders were bunched up tight as if against the wind, a defensive posture. The vague face was thin and lined; the long dark hair was lank and uncombed, falling over those tight shoulders in untidy clots. A shapeless coat of indiscriminate gray was draped over dark clothes. The man plunged his hands into his pockets. His face was turned slightly down. He was looking at Saul from beneath his brows.

A smell of rubbish and wet animals filled the room. The man stood motionless, watching Saul from across the floor.

“You’re safe.”

Saul started. He had only dimly seen the man’s mouth move, but the harsh whisper echoed in his head as if those lips were an inch from his ear. It took a moment for him to understand what had been said.

“What do you mean?” he said. “Who are you?”

“You’re safe now. No one can get to you now.” A strong London accent, an aggressive, secretive snarl whispered right in Saul’s ear. “I want you to know why you’re here.”

Saul felt dizzy, swallowed spit made thick with phlegm by the atmosphere. He did not, he did not understand what was happening.

“Who are you?” Saul hissed. “Are you police? Where’s Crowley?”

The man jerked his head in what might have been dismissal, shock, or a laugh.

“How did you get in?” demanded Saul.

“I crept past all the little boys in blue on tippy-toe. I slid hugger-mugger under the counter and I sneaked my way to your little queer ken. Do you know why you’re here?”

Saul nodded dumbly.

“They think…”

“The constables think you killed your daddy, but you didn’t, I know that. Granted, you’ll have a fine time getting them to Adam and Eve that… but I do.”

Saul was shaking. He sank onto the bunk. The stench which had entered with the man was overpowering. The voice continued, relentless. “I’ve been watching you carefully, you know. Keeping tabs. We’ve a lot to talk about, you know. I can… do you a favor.”

Saul was utterly bewildered. Was this some casualty off the streets? Someone ill in his head, too full of alcohol or voices to make any sense? The air was still taut like a bowstring. What did this man know about his father?

“I don’t know who the fuck you are,” he started slowly. “And I don’t know how you got in…”

“You don’t understand.” The whisper became a little harsher. “Listen, matey. We’re out of that world now. No more people and no more people things, get it? Look at you,” the voice harsh with disgust. “Sitting there in your borrowed duds like a fool, waiting patiently to get took before the Barnaby. Think they’ll take kindly to your whids? They’ll bang you up till you rot, foolish boy.” There was a long pause. “And then I appear, like a bloody angel of mercy. I spring your jigger, no problem. This is where I live, get it? This is the city where I live. It shares all the points of yours and theirs, but none of its properties. I go where I want. And I’m here to tell you how it is with you. Welcome to my home.”

The voice filled the small room, it would not give Saul space or time to think.

The shadowy face bore down on Saul. The man was coming nearer. He moved in little spurts, his chest and shoulders still tight, he approached from the side, zigzagged a little, came a little closer from another direction, his demeanor at once furtive and aggressive.

Saul swallowed. His head was light, his mouth dry. He fought for spit. The air was arid and so full of tension he could almost hear it, a faint keening as if the sound of the door hinge had never died away. He could not think, he could only listen.

The stinking apparition before him moved a little out of the shadows. The filthy trenchcoat was open, and Saul caught sudden sight of a lighter gray shirt underneath, decorated with rows of black arrows pointing up, convict chic.

The angle of the man’s head was proud, the shoulders skulking. “There’s nothing I don’t know about Rome-vill, you see. Nor Gay Paree, nor Cairo, nor Berlin, nor no city, but London’s special to me, has been for a long time. Stop looking at me and wondering, boy. You’re not going to get it. I’ve crept through these bricks when they were barns, then mills, then factories and banks. You’re not looking at people, boy. You should count yourself lucky I’m interested in you. Because I’m doing you a big favor.” The man’s snarling monologue paused theatrically.

This was madness, Saul knew. His head spun. None of this meant anything; it was meaningless words, ludicrous, he should laugh, but something in the curdled air held his tongue. He could not speak, he could not mock. He realized he was crying, or perhaps his eyes were just watering in the stagnant atmosphere of the room.

His tears seemed to annoy the intruder.

“Stop moaning on about your fat dad,” he spat. “That’s all over, and you’ve more important things to worry about.”

He paused again.

“Shall we go?”

Saul looked up sharply. He reached his voice at last.

“What are you talking about? What do you mean?” He was whispering.

“Shall we go? I said. It’s time to scarper, it’s time to split, to quit, to take our leave.” The man looked about him conspiratorially, and hid his mouth behind the back of his hand in a melodramatic stage whisper. “I’m breaking you out.” He straightened up a little and nodded his head, that indistinct face bobbing enthusiastically. “Let’s just say your path and mine cross at this point. It’s darkmans outside already, I can smell it, and it looks like they’ve forgot about you. No Tommy Tucker for you, it seems, so let’s bow out gracefully. You and I’ve got business together, and this is no place to conduct it. And if we wait much longer they’ll have banged you up as a member of the parenticide club and eaten the key. There’s no justice there, I know. So let me ask you one more time… shall we go?”

He could do it, Saul realized. With a terrified amazement he realized he was going to go with this creature, was going to follow this man whose face he could not see into the police station, and the two of them would escape.

“Who… what… are you?”

“I’ll tell you that.”

The voice filled Saul up and made him faint. The thin face was inches from his, silhouetted by the bare bulb. He tried to see through the obfuscating darkness and discern clear features, but the shadows were stubborn and subtle. The words mesmerized him like a spell, as hypnotic as dance music.

“You’re in the presence of royalty, mate. I go where my subjects go, and my subjects are everywhere. And here in the cities there’re a million crevices for my kingdom. I fill all the spaces in-between.

“Let me tell you about me.

“I can hear the things left unsaid.

“I know the secret life of houses and the social life of things. I can read the writing on the wall.

“I live in old London town.

“Let me tell you who I am.

“I’m the big-time crime boss. I’m the one that stinks. I’m the scavenger chief, I live where you don’t want me. I’m the intruder. I killed the usurper, I take you to safekeeping. I killed half your continent one time. I know when your ships are sinking. I can break your traps across my knee and eat the cheese in your face and make you blind with my piss. I’m the one with the hardest teeth in the world, I’m the whiskered boy. I’m the Duce of the sewers, I run the underground. I’m the king.”

In one sudden movement he turned to face the door and sloughed the coat from his shoulders, unveiling the name stencilled crudely in black on the back of his shirt, between the rows of arrows.

“I’m King Rat.”

Excerpted from King Rat, copyright © 2023 by China Miéville.