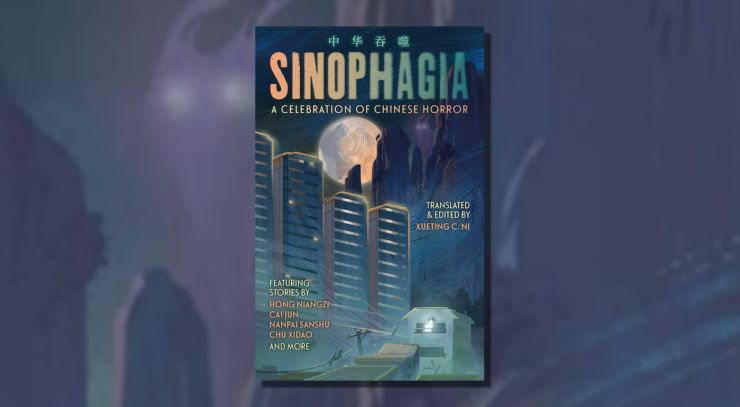

We’re thrilled to share editor Xueting C. Ni’s introduction to Sinophagia: A Celebration of Chinese Horror. This anthology of unsettling tales from contemporary China, translated into English for the very first time, is available now from Solaris.

From the menacing vision of a red umbrella, to the ominous atmosphere of the Laughing Mountain; from the waking dream of virtual working to the sinister games of the locked room… this is a fascinating insight into the spine-chilling voices working within China today—a long way from the traditional expectations of hopping vampires and hanging ghosts.

This ground-breaking collection features both well-known names and bold upcoming writers, including: Hong Niangzi, Fan Zhou, Chu Xidao, She Cong Ge, Chuan Ge, Goodnight, Xiaoqing, Zhou Dedong, Nanpai Sanshu, Yimei Tangguo, Chi Hui, Zhou Haohui, Su Min, Cai Jun, and Gu Shi.

Introduction to Sinophagia (redacted)

I have always had an active imagination. I was the sort of child who would see all kinds of things in the indistinct shapes of the dark, and of course, I loved ghost stories.

One of my earliest memories of horror was watching the 1986 TV adaptation of Pu Songling’s famous Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio. Its opening titles, a single, dimly lit lantern, hovering unsteadily over a desolate nocturnal field, to the sound of ghostly, whispering wind, gave me unspeakable chills. During my childhood in Guangzhou, I would often visit Yuexiu Park, which housed a replica of the underworld scenes from the fantasy epic Journey to the West, meaning I could visit the grim scenes repeatedly. I remember really wanting to live in a cave like the White Bone Demon.

This fascination with fear is natural to us all. This emotion is one of the primal human urges, and whilst it is not one that everyone finds easy to face or admit, or even one that certain societies and cultures are comfortable presenting to the world, we need the ability to be afraid in order to truly know what it is to be brave, calm and safe. One of the things I appreciate in both the writers and readers of horror, is their willingness to face fear.

After moving to the UK, I fell in love with gothic fiction. I spent an adolescence reading authors such as Charlotte and Anne Brontë, Wilkie Collins, Alexandre Dumas, before following them with the likes of Horace Walpole, Charlotte Gilman Perkins and R.L. Stevenson at university. As an adult, I also found myself sitting down to Hammer horror films, eighties American cult classics and Hong Kong zombie films, and later finding out about mainland Chinese Qingming and Zhongyuan releases. I was drawn to the likes of Susan Hill’s The Woman in Black, and films like Guillermo Del Toro’s The Orphanage. Whilst gore has its place, it does not affect me nearly as much as that suggestive sense of eeriness.

The Chinese view of Horror has always struck me as being unique. Where nearly every horror myth I have come across in the West is a cautionary tale, China has a long tradition of journal and documentational style writing, referred to as the zhiguai, or tales of the strange, that mixes history with legends and hearsay. Moreover, the mishmash of Chinese beliefs did not label spirits and ghosts as something evil and unnatural, but rather, just part of the normal order of things, with their own place in the world, and traditionally, the ‘frights’ have only arisen when the spirits are angered, restless, or the boundaries trespassed.

As I began to put this collection together, I came upon a new horror. The more I spoke with agents and editors in China, the more I discovered that there had been a certain ‘poisoning’ of the genre through a slew of gratuitously violent, gory, and sexualised content, and a string of real-life deaths, all of which were blamed on the copying of films, books and series with a horror theme. My own research had shown me that China’s horror fiction was at the same stage science fiction had been around a decade ago and would also be ready to find an international readership, but whilst there was an amazing love for horror literature here in the West, it seemed that people did not want to be known as horror writers within China. I had paved my way into China’s publishing industry with my first collection, but even with these contacts and avenues, how could I find those excellent writers I had read and written about, if they did not want to be found? There had been several online short story platforms specialising in horror, which would have been perfect selection pools, all of which seemed to have shut up shop at the start of the pandemic, and never reopened.

Buy the Book

Sinophagia: A Celebration of Chinese Horror

However, I was not going to give up. I was going to find these voices, by any means. I emailed, sent voice messages, held international phone conversations, stalked and pestered people (in an amicable and courteous manner) on social media, and did my best to explain that Horror fiction is much more established and recognised in the Anglophone market. I could see there was a lot of excellent writing in this genre from the last thirty years, especially around the period of domestic boom, which readers around the world would find fascinating and love to read. I thought how tragic it would be to see these works and creative voices buried. I hoped to gain new recognition for these writers with my anthology, and for this positive interest outside of China to feed back to the domestic market, in the same way it had done with kehuan (science fiction), and we may just be able to alter attitudes and perspectives within the country.

I held my breath, but my already low expectations were lowering still, until one day, my heart leapt at the notifications on my phone. Whether it was the earnestness of my words, the desperation in my tone, my sheer bloody-mindedness, or the scent of opportunity, they started to respond.

The next few months were punctured by immense ups and downs. Word of mouth about the project opened more and more doors, until I had a submission pile threatening to crash my little inbox. I read and read until my eyes felt ready to pop out of their sockets, but this was still only half the battle. I now had access to works and writers in the genre, but assembling the collection I wanted was going to take very careful curation. I have often said that Chinese literature is either very short, or very long, and in horror, it seemed like the best writers worked predominately in the long form. It took a lot of cajoling and discussion to convince writers to share shorter pieces with me or let me take stories out of the context of larger collections, to try and merge those with some shorter pieces, “Tetrising” them into a collection I feel shows the gamut of contemporary China’s Horror scene.

Whilst this collection is meant to introduce you to the wonders, and terrors, of Chinese Horror, it is still climbing out of a pernicious, exploitative era, and in doing so, many current attitudes and the representation of genre in China are problematic, and that extends all the way down to what you actually call it. For example, whilst there are specific terms for certain sub-genres, such as lingyi (paranormal), the most common term for Horror as a whole, is kongbu wenxue, the same “kongbu” (恐怖) that is the term used for Terrorism. Understandably, the word is filled with negative connotations. An alternate name for Horror is jingsong wenxue, but jingsong (惊悚) meaning “shock and fright”, has come to be the Chinese equivalent of the term “Grindhouse”, or “Goreporn”.

Neither of these terms really describe Horror beyond the most superficial and stereotypical elements of storytelling, and certainly fail to illuminate exactly what this kind of literature is really about. Most horror writers I spoke to in collecting these stories preferred to use the term 悬疑 xuanyi (suspense), or thrillers, which puts them on the same shelves as spy stories, or detective novels. In not naming a genre, or employing euphemisms, we risk it disappearing from literary history.

I have, in my correspondence, used the term kongxuan(恐 悬), in an attempt to invite a more nuanced approach to the genre, and express its diverse nature. A constant reminder that Horror is a lot more than jumps, shock, and gore, though each of those has its place. It tells of the fearful things we encounter around us, and within ourselves.

My first collection of Stories, Sinopticon, was very much about the visions of China, but Horror is a far more visceral thing, and whilst this may be considered a companion piece, I also wanted it to stand out as its own thing. We wanted a title that sounded unsettling, but without fuelling any sense of Sinophobia. ‘-Phagia’ was chosen because of its association with ‘devouring’. If any student studying this is seeking to increase their wordcount, you could consider it an ironic statement regarding the rising Sinophobia around the world, rooted in unfounded fears surrounding Chinese and Asian eating habits.

The writers in this collection are varied. Not just in style, but age, gender, background and importantly, location. Whereas science fiction by nature transcends geographical boundaries, Horror traditions are intensely regional, with strong emotional energies, such as fear, very much embedded in our natural and manmade surroundings. Sinophagia reflects a society still dealing with recent histories of war, invasions, and revolutions, who still have a deep-rooted connection to a land that has not always been hospitable, and a cultural memory of the dangers brought by floods, famine, and the inhospitable terrain which surrounds the flatter cradle of early civilisation. What emerges is a very regional horror landscape, with the ethnically diverse mountains of the South and West, such as the imposing Zhangjiajie range of Xiangxi, providing the perfect sublime, but terrifying backdrops, whilst the equally impressive glass and steel ‘mountains’ springing up through urbanisation, fulfil the 21st century literary imagination to engage with the real-life horrors around them. In Sinophagia, we see a contemporary society that is concerned about class, the rural and urban divide, unaffordable housing, the aftermath of biopolitical policies, the alienating impact of urban living and how the growing consumerist economy and overwhelming pressures of the jobs market affect businesses and families. Whilst these issues are present in many non-genre books in China, they are often downplayed, or given imaginary happy endings, or in typical Chinese fashion, endured for a greater good. Horror allows the suffering in these situations to be explored unchecked, and often unresolved.

One thing that I have really enjoyed about putting this collection together, has been the way Horror plays with perspective and voice, and there is certainly a vast array in this book, from conventional omniscient narrators and intimate first-person storytelling, to an unusual second person viewpoint, and the marginalised voices of the non-human and non-mortal. There are neurodivergent characters, and those who are being deliberately misled or manipulated, and sometimes, a combination of these, suddenly, rapidly switching, which make the stories all the more interesting. Whilst the styles and tones vary from story to story, from literary to journal-like reportage, from grave voices of gravitas, to the darkly comical, each of them has a sense of the uncanny, with themes of entrapment, secrecy and concealment, running through them. I truly believe that many of these stories can be read as archetypes for “The Chinese Gothic”.

—Xueting C. Ni

Table of Contents

- The Girl In the Rain 雨女 by Hong Niangzi

- The Waking Dream 清醒梦 by Fan Zhou

- Immortal Beauty 红颜未老 by Chu Xidao

- Those Who Walk At Night, Walk With Ghosts 但行夜路必见鬼 by She Cong Ge

- The Yin Yang Pot, 鸳鸯锅 by Chuan Ge

- Shanxiao 山魈 by Goodnight, Xiaoqing

- Have You Heard of Ancient Glory? 你听说过古辉楼吗?by Zhou Dedong

- Records of Xiangxi 老九门之湘西往事 by Nanpai Sanshu

- The Ghost Wedding 喜结鬼缘 by Yimei Tangguo

- Night Climb 夜攀 by Chi Hui

- Forbidden Rooms 禁屋 by Zhou Haohui

- Ti’Naang 替囊 by Su Min

- Huangcun 荒村 by Cai Jun

- The Death of Nala 娜娜之死 by Gu Shi

Excerpted from Sinophagia: A Celebration of Chinese Horror, copyright © 2024 by Xueting C. Ni, published by Solaris.