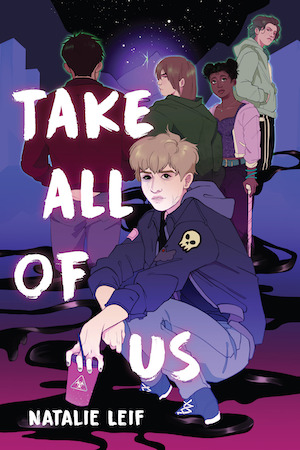

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from Take All of Us, a new young adult horror novel by Natalie Leif—publishing with Holiday House on June 4th.

Five years ago, a parasite poisoned the water of Ian’s West Virginia hometown, turning dozens of locals into dark-eyed, oil-dripping shells of their former selves. With chronic migraines and seizures limiting his physical abilities, Ian relies on his best friend and secret love Eric to mercy-kill any infected people they come across.

Until a new health report about the contamination triggers a mandatory government evacuation, and Ian cracks his head in the rush. Used to hospitals and health scares, Ian always thought he’d die young… but he wasn’t planning on coming back. Much less face the slow, painful realization that Eric left him behind to die.

Desperate to find Eric and the truth before the parasite takes over him, Ian along with two others left behind—his old childhood rival Monica and the jaded prepper Angel—journey to track down Eric. What they don’t know is that Eric is also looking for Ian, and he’s determined to mercy-kill him.

The itch to say I love you rattled inside me for the rest of the evening, around a tasteless taco dinner and mindless homework attempt, and all

through a long night of waking up dry-eyed and sleepless every half hour. I finally cracked around eight a.m., when Eric might be awake, and I sent him a text to meet me at the mall like I had something important to tell him.

What I was going to tell him, how and when and where, I had no idea about.

Eric, I love you. I don’t mean like a friend, I mean more than that. I want to… date you? Kiss you? Marry you?

Eric, I am IN LOVE with you. I don’t care if you’re a boy. I get if that ruins our friendship for you, and you want to leave forever and never look back—

No, that ain’t true, I wouldn’t get it. I don’t want to lose out on spending lazy summer days together like this. So if you don’t love me back, let’s both pretend I never said anything. Got it?

But… if you DO somehow love me back, maybe we could kiss? Just once, real quick. No one would have to see, promise.

I buried my head in my hands, scrubbing against my eyelids until my vision flared red. None of those sounded right. Even in my own head, I sounded hesitant and slow, the sort of person you could only love out of a strange sense of pity.

All this seemed like a bad idea, now.

Too late for that, I guessed. I’d already made it to the mall. I’d already sat down on the edge of the fountain, on plaster that smelled like chlorine and mildewed coins.

And he was already settled next to me, drinking pop out of a water cup, waiting for me to confess whatever big damn secret I had.

Once upon a time, the Kittakoop mall was somewhere important. It was built that way, with a long, wide hallway and a dozen off-shoot stores, with lush potted plants along the walls and speakers piping synth-pop Muzak overhead. Maybe it was built with the expectation that we’d grow into it, like little kids in hand-me-down clothes.

Nowadays, though, it sat half empty, its big hallway caked with dust in the corners and that same handful of Muzak songs cycling through static. The plants still looked nice, though their plastic threads had frayed at the edges and the glue showed through in spots. Half the stores stood empty, their security grilles drawn and their insides a dark mass of cardboard boxes, while the other half cycled through brands every year or two: first a hair salon, then an insurance company, then a Chinese takeout place. Only the clothing store seemed to stay every year, a single corporate mass keeping the mall barely alive. Every so often a person or two would mill past us, their footsteps echoing across the tile, and I watched them for the sake of something to do that wasn’t trying to find words. My eyes flickered from them, to my hands, to the scattered coins rippling under the fountain’s shallow pool behind us. The air-conditioning rattled, too cold and stale, cutting through the faded purple jacket I’d thrown on.

Buy the Book

Take All of Us

Beside me, Eric pulled out the battered lighter he always fiddled with when bored or restless. He lifted a tanned arm, exposing an inch of bare skin under the edge of his tugged-up shirt… and opened an eye to watch me.

“What?” he asked.

“It’s just…” I took a deep breath, let it out again. “It’s nothing. Never mind.”

And it could be nothing. It could be nothing, and we could both go home, and soon enough it’d suffocate under the weight of all that nothing, and the world would keep spinning round, and it’d be fine.

That’d be the safest option, too. No one could blame me for being too safe. We’d moved to West Virginia in the first place to be safe, because I’d had a grand mal seizure on the kitchen floor and suddenly the city was too full of strobe lights and flashing signs and alarms blaring DANGER, ALERT, EMERGENCY, everything the doctors told me to avoid.

I could imagine just about all those signs now. They sat on any path toward talking about my feelings, blaring and bright and not giving a whit about the medical alert bracelet on my wrist that said EPILEPTIC. “It don’t seem like nothing,” Eric said. He flicked the lighter, flick-flick-flick, and I bit back an itch to slap it out of his hands and remind him that you don’t even smoke, you just like looking at the fire.

DANGER, went my brain. “Well, it is.”

“You called me all the way out here for nothing?”

DANGER. ALERT. NO ACCESS.

“Yeah. Guess I must’ve forgot what it was. Probably wasn’t important. You want to get takeout or something instead, while we’re here?”

“Uh-huh. And now you’re changing the subject. Come on, fluffy.”

DANGER. EMERGENCY.

“I told you, it’s not a big deal. I’ll tell you later, promise.”

“Wait, which is it? ‘I forgot’ or ‘I’ll tell you later’?”

DANGER, DANGER, DANGER, DANGER.

“It’s both. Neither? Look—” I couldn’t get that flashing siren out of my head, and I squeezed my eyes shut. “I just don’t want to ruin things—”

“Ian—”

“I don’t want you to think I’ve just been creeping on you, but ever since I realized it’s been hard to stop thinking about it—”

“Ian—”

“I can’t hardly think right now, even, I—”

“Ian, stop.” Eric pressed a hand to my arm. “What the hell?”

I stopped, but that siren didn’t, and I realized with a start that it wasn’t in my head. High overhead, next to the skylights, tiny lights flashed sharp white, casting the mall kiosks and plants into searing silhouettes. An alarm warbled in and out, and the speakers crackled, that soothing Muzak drowned out by a distorted recording.

“State of—Evacuate—warning—please—from the building— This is—” a man’s voice echoed, thundering across the hall.

It kept on, but all I could really notice were those lights. They flashed over and over, searing neon, and as I stared at them I felt the taste of sour copper and spit gather in my mouth, along with a dizzy floatiness somewhere behind my eyes.

No, I thought. Then: no, no-no-no, not again.

I couldn’t hear Eric’s voice anymore, but I saw him hold up a hand: stay here. I saw him stand up, and I mouthed the words, help me, at the back of his head. His shirt flared a sickly reddish-orange, smearing across my vision as he moved—him surging forward in bursts of feverish white light toward the exit, me fainting backward into the fountain, and that siren still screaming, screaming, screaming over both of us.

Then I hit the water, and the back of my head cracked hard against the tile, and everything went from a carousel of electric colors to brilliant white. I tasted copper and chlorine, mixed together in a mouthful of cloudy red bubbles, and… it was funny.

Under a foot of stale fountain water, the alarm didn’t sound so loud. It drifted into my ears from somewhere far away, along with echoes of EVACUATION and BUILDING and STATE…and, over it all, somehow, still that gentle shopping mall Muzak, crooning gently on. Even the light didn’t seem so bad, distorted by ripples.

I wondered, absently, if this was how non-epileptics got to see alarms: as distant, casual things, acknowledged and ignored, the kind of things they could look directly at and then away from without once wondering if it’d be the thing that killed them.

It seemed nice.

I watched the light sparkle like stars as I choked down another lungful of water, listened to buzzing synths and happy drumbeats as my vision faded from white to pooling black, and it did seem so nice. I sank into it like Mr. Owens did, letting it settle into my aching joints and racing heart and overwhelmed head.

And it all went dark.

* * *

I can’t remember what happened after that, except in fragments.

Someone pulling on me, yanking me out of the water. Eric’s voice, frantic and shouting and stumbling all over itself. A rush of cold air against my face, the taste of old pennies against my teeth. Trying to breathe, failing, panicking. Throwing up mouthfuls of pinkish water onto the floor, the splash of it against cement. Taking thin, reedy breaths I coughed back out, burning in my throat. Dropping, curling up on my side, lights still too bright, fluorescents buzzing like wasps. Running footsteps. The hallway—a potted plastic fern—sticky dark blood against my fingertips, too much, everywhere—the cool comfort of a shadowed corner, the black slab of an OUT OF ORDER vending machine—a pounding in my head, needles and hammers against my skull—sinking into a corner, burying my face in my jacket hood—shaky legs and a bone-deep tiredness—

And a long, long quiet.

* * *

The worst part about seizures was never the seizure itself. I fainted through those, or otherwise got so fuzzy-headed that I forgot them before they were over.

Nah, the worst part was always afterward: waking up disoriented on a floor somewhere new, head full of cotton stuffing and a sour burnt taste in my mouth. Shaking pins and needles out of heavy limbs, checking if I’d pissed myself again, feeling up and down for all the new bruises and cuts and aches I’d have to carry home. If I was really unlucky, there might be a couple onlookers or a cop there, too, gawking and throwing out questions like what the hell happened to you?

No watchers this time, at least. Hadn’t pissed myself, either, somehow. Or I had, and falling into old fountain water made it hard to tell. I decided to pretend I hadn’t.

When I finally felt stable enough to lift my head—with the pounding and nausea faded into something just south of excruciating—I pushed myself upright. The siren and flashing lights were gone, and the peppy Muzak, too, leaving a silence deep enough to bask in. I savored it for a second, then, all at once, I remembered being pulled out of the water. I remembered Eric’s voice, shouting noises that didn’t settle into words but damn sure settled into fear.

Of course. Eric always knew what to do. After years together, he’d become a natural at noticing the signs of a seizure, getting me situated in a safe place, and shooing away anyone who wanted to rubberneck. He must’ve run back from the entrance as soon as he saw me flailing underwater like an idiot.

So I raised a hand and forced a smile, in case he was lurking somewhere close.

“ ’M okay,” I rasped. “Still here. Thanks for the save.”

No answer. I squinted around, raising a hand to shield my eyes from even the faint skylights of the mall.

“Eric?”

Eric wasn’t here. Neither were any of the other shoppers we’d seen milling around. The mall sat dim and empty, a wide swath of shuttered storefronts and drifting dust motes. The only lights I could see were the skylights letting in shafts of hazy afternoon sun… and the vending machine beside me, its face glowing with shadows of cola cans and water bottles. Its motor hummed somewhere inside, and the fountain kept burbling on down the hall, but everything else sat quiet and dead.

Dead. At the word, the back of my head gave an angry throb, and I cried out and pressed a hand to it.

It felt sticky and somehow soft, like a baby’s head where the bones haven’t quite shaped all the way yet. I pushed at it and it hurt in a dizzying way, a little button I could press to knock myself out of my senses for a bit.

My hand came back bloody. Not just a smear, either, but a whole handful, welling into my palm and leaking between my fingers as I stared.

One mercy of waking up post-seizure: I always woke up too tired to know if I should be scared yet. I could get up, get my bearings, and tidy up most of any mess before I came to enough to panic about it.

So when I saw the blood pooled in my hand and felt it trickling down the back of my neck, I didn’t scream, even when I realized in a vague way that it’d be a good time for it. I got up instead, swaying with vertigo, and staggered down the hall past all those grated storefronts and toward the nearest bathroom. A family bathroom, it turned out, one of those kinds with a single room and a baby changing station and a toilet that only came up to my shins.

And a mirror. I caught myself against the sink, smearing blood all across its pretty white porcelain, and I looked up at myself.

And I realized I was dead.

The eyes gave it away first, as they always did. I’d always had a round face and a scrawny build, as if after years of health scares my body had given up on growing somewhere around age twelve. It’d been what made me and Eric match—him pushed to grow up too soon, me stuck behind, and both of us meeting in the middle, where we were supposed to be. But now I had big black doll eyes to go with all that, nestled above purple shadows in a milk-pale face like a ceramic figurine, and that doll-me in the mirror seemed as shocked by it as I did.

Everything else came with its own flavors of wrong, too. My hair hung in blond fluffs over my forehead, dry in the front, plastered to my neck in chlorine-dark blood-clumps in the back. The jacket I’d thrown on hung waterlogged on my shoulders, all my careful iron-on patches of skulls and monsters and other cool things—slapped on in a desperate attempt to seem at least a little badass—were dyed pinkish-orange from the water. Even my shirt fit wrong now, its collar tugged askew and sleeves rolled up somewhere between falling and thrashing back up.

Just like Mr. Owens, I thought. A little less out of it, a lot less sunburned, but otherwise we could be cousins.

And all of a sudden, I started laughing. I laughed way too hard, coughing it up and wheezing it back down, and I pressed a red-smudged hand to my face just to keep it steady.

“Holy shit,” I breathed. “I really messed up, now.” Another laugh. “What a stupid way to die.”

I couldn’t stop laughing. Because it really was funny, in that awful-funny way. All the ways I could have died—hell, all the things that had tried to kill me already, from seizures to allergies—and I died in a foot and a half of rusty fountain water.

This shouldn’t have even happened. I did so good, living in the fancy side of town and drinking filtered water and eating organic food . . . except mall fountains didn’t have water filters, did they? Mall fountain water wasn’t clean enough to drink from or to die in. It didn’t matter if I’d lived like a rich person expecting a quiet death—I’d died like an old country man with a lungful of used fountain water.

Like the letter from the government warned about: Sorry. Our mistake. Here’s three hundred dollars. Buy a water filter. Eat uncontaminated food. Consider moving. Push your neighbors into a lake.

Or maybe I’d already been doomed like this. Maybe I’d contaminated myself with some school water fountain, or a drink from a vending machine. Maybe I was always gonna die stupidly and wake back up mad about it.

I didn’t even get to see what the alarm was about; it could’ve been a fire, or a terrorist attack, or a tornado, or anything else that would’ve killed me with some sort of dignity. Maybe I could have even been a hero, rescuing a dozen orphan kids before collapsing from smoke inhalation.

Eric would’ve found it funny, if he was here. Only Ian Chandler, fifteen-year-old walking crisis, could fail an evacuation so hard he died. Only Ian Chandler could get so flustered at being gay that he slipped on a tile and cracked his head open and let all the brains spill out.

Only Ian Chandler could die in a mall fountain before he’d even tried living first.

I kept laughing until I teared up, until the tears started streaming down my face between chuckles, until I curled up on the floor and I laughed and I laughed and I screamed myself hoarse.

Excerpted from Take All of Us, copyright © 2024 by Natalie Leif.