When the Dragon Ships began to tear through the trade lanes and ravage coastal towns, the hopes of the archipelago turned to the Windspeakers on Tash. The solemn weather-shapers with their eyes of stone can steal the breeze from raiders’ sails and save the islands from their wrath. But the Windspeakers’ magic has been stolen, and only their young apprentice Shina can bring their power back and save her people.

Tazir has seen more than her share of storms and pirates in her many years as captain, and she’s not much interested in getting involved in the affairs of Windspeakers and Dragon Ships. Shina’s caught her eye, but that might not be enough to convince the grizzled sailor to risk her ship, her crew, and her neck.

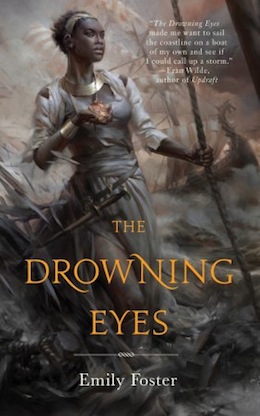

The Drowning Eyes, Emily Foster’s vividly rendered debut novella, is available January 12th from Tor.com Publishing.

Chapter 1

“Not in this lifetime.” Tazir snatched two of the pebbles off of the pile for the equipment budget. “Or at least not after what you pulled coming into Hanshi.”

Her hatchet-nosed quartermaster locked her amber eyes on Tazir’s. “I told you, Cap, just because I can hack that together in a pinch don’t mean I plan on doing it every—”

“And how are we not in a pinch?” Tazir asked, dropping the pebbles back on the greasy wooden bartop with the rest of the pile for food.

Chaqal opened her mouth to say something, but Tazir could see her eyes taking in the scene around them. Young as Chaqal was, she had the good sense to be leery of this place—not so much an inn as a dockside canopy set up above a stack of rum barrels and the square bar surrounding them.

It had shade, and it had rum, and in the evenings it had a couple ribby dancers who came around to rub up against the customers—but ah, the customers. Whether tall and sinewy or short and ham-legged, whether adorned with tattoos or deliberate scars, whether trained with a hook-head spear or a Bahenji swinging club, the customers were bad news. It didn’t matter if they belonged to a tribe or an island or just a merchant Captain with a lot of cash to drop on security. Unless you were talking to a dancer, the barkeep, or someone you knew, you kept your eyes down and your elbows in tight while you were drinking at Shasa’s.

Chaqal glared at her little pile. “Can I just get one more dak?” she asked.

Tazir’s eyebrows sank together. “Can you just eat a little less?”

On Tazir’s other side, her first mate cleared his throat. “If it helps,” he said, “I’m inclined to give her both dakki and count on this passenger for the rest of your food money.”

“Dammit, Kodin,” Tazir said, rubbing her weathered forehead. “Look, we have no idea if we’ll even find anyone.” It had been her idea, coming to Shasa’s to pick up one of the travelers who came through looking for a cheap ride who didn’t ask too many questions. Last time she was in this place, it had been buzzing with “runaway bride” and “looking for my brother” and even the odd, honest, “I killed someone back in my hometown and I need to get halfway across the ocean as fast as I can.”

But last time had been almost a year ago, and nobody had even heard of the Dragon Ships back then. Since last time, Shasa’s had been gripped by the same fear and paranoia that was keeping the Giggling Goat out of her usual fishing grounds. No one—neither the goldsmiths of Luraina nor the blind weather witches of Tash—was safe from the vicious raiders in their fast ships, which meant that precious few people wanted to go anywhere. The ones who did preferred to travel with the most imposing and warlike crew they could find.

Now, although Tazir was deceptively strong and weathered by the sun and sea, she was just a little over five feet tall and slightly built. When it came to “imposing and warlike-looking,” she just wasn’t going to outdo the tall glowering women three seats down with intricate scars cascading down their broad shoulders and powerful legs. Or the trio of boulder-shaped Gurni men at the other corner, eyeing the crowd for passengers as blatantly as she and her crew were.

Chaqal could actually fight like a demon, but she looked even less warlike than Tazir. With big bovine eyes and plump, round lips, she still looked fifteen seven years after the fact. It didn’t help that she liked to wear a long, flowing skirt and a tunic printed with flowers when she wasn’t on the boat.

Of the three of them, Kodin looked the most useful in a fight. In fact, it was because of Kodin that their presence went unquestioned in Shasa’s—he used to do security with someone’s brother, who fought in a war down south with someone else’s cousin, and so on and so forth. From what Tazir knew, he’d been good at security. He certainly looked the part. Tall and wide, with big square shoulders and big square fists, Kodin was built to make people cooperate. Even now that his fighting days were (mostly) done and his bushy beard was starting to show white, all it took was a stern look from him to get most people to quiet down.

Together, the three of them were mean ugly enough that they’d had travelers rely on their protection in a pinch when they needed safe passage from one place to another. But, again, the last time that had happened, the Dragon Ships had not yet appeared on anybody’s horizon. Now that they’d hit storm temples on Vura and Tash, everything had gotten a little bit harder.

“We should go somewhere else,” Chaqal said, looking around. “In here, we look more like passengers ourselves.”

“We won’t be better off,” Kodin said. “Those guys who left were saying the wind is shut down from Kahiri to Nua’ali.”

Tazir shut her eyes for a moment, thinking of the havoc that was going to cause. “Perfect,” she said. “The Dragon Ships don’t need to bother burning our ports anymore—just scare us all until we lock ourselves in and starve to death.”

“It’s not that bad,” Chaqal said.

“I don’t know.” Kodin flattened his lips. “Last time the Windspeakers shut down that much water, it started all kinds of trouble—fighting, riots, all the shit bored people do when they run out of money.”

“But they can’t just—just shut down all the wind,” Chaqal asked. “Can they?”

“I guess sometimes,” Tazir said, “when things are bad enough. Like last time, they had that bleeding fever over on Nderema, and they calmed the water for twenty miles in every direction until it was gone.”

“When I was a kid,” Kodin said, “we had these three pirate boats just wrecking people all over the place for no reason. Nobody could catch them until a Lurainese Shadowguard saw them in Luraina’s waters. The Windspeakers had to shut down the entire island to give the Shadowguards a chance.”

“Is that what they’re trying with the dragon boats?” Chaqal asked. Instead of answering, Kodin picked up his wooden cup. He glared straight ahead as he drank the thick black rum inside, and Chaqal kept nursing her own drink. “Anyway,” she said to Tazir. “I’d worry a lot less if I had a little more money to throw at repairs.”

“I’ll give you one more dak,” Tazir said. “But if we run out of money next time we make port, you’re dancing on the tables.”

“Hey, that means we’re going somewhere nice, right?” Chaqal laughed, raucous barks of joy that seemed too big for her frame. “Yeah, fine, I’ll take the one dak and stop pestering you. For now.”

“Like you could just stop.” Tazir plunked the pebble from the food budget back on the equipment budget. “Hey, Kodin,” she said. “You want to write this down?”

The first mate dug in one of the pockets inside his embroidered vest until he found his tablet. He spit on his thumb and rubbed a corner clean, then started copying the budget down with the urba shell stylus tied to another corner.

“You’re final on seven dakki for bribes?”

“I hope so,” Tazir said. The Dragon Ships hadn’t driven the cost of doing business up that high, but she was certain she’d find some port officer who disagreed.

Kodin finished copying the budget and snapped the tablet’s leather cover shut again. “We’ve been tighter,” he said.

“Yeah?” Tazir snorted, and spit on the ground. “When we had Mati on board, maybe.”

“Maybe.” Kodin gave her a halfhearted nod. “She did like her white wine.”

Tazir shook her head and knocked on the bar for another drink. “The shit I did for that woman,” she muttered at her knuckles. White wine, and a fortune’s worth of it—now that was a way to remember a marriage. “Feh. It doesn’t—”

“Hey,” Chaqal said. She tapped Tazir on the shoulder and pointed to her right. “Coming down the dock. In the green.”

Tazir turned her head to see who Chaqal was talking about. It didn’t take her long. Tall and gangly, in a long skirt and short blouse of fine green silk, the kid stuck out like a sore thumb among the sailors and sellers who crowded Humma’s spiderweb of docks. She wore her wiry black curls cropped close to her head like Mati used to. She was walking with her shoulders pinned together behind her back, and her eyes’ frantic back-and-forth betrayed the calm on her pretty round face.

“Jingle, jingle, jingle,” Tazir said to Kodin.

He grunted with laughter, then turned to her with a jerk. “Wait,” he said. “You’re serious?”

Tazir was already straightening her creaky hips as she stood on the dock. “I’ll be back,” she said. “With company.”

“Captain, I’d bet money another crew’s already—”

Tazir laughed and swaggered down the dock toward the girl. “Excuse me, ma’am,” she said, holding her hand up as she approached. The girl stopped. A man walked right into her from behind and swore loudly in Djahrna.

“Sorry,” the kid said, turning around and pulling her skirt out of his way as he picked up a bundle he’d dropped.

“Don’t know where the fuck you think you from, girl—”

The girl’s face darkened with embarrassment as the man made his way down the dock.

“Excuse me,” Tazir repeated, stepping up to the girl and tugging at the sleeve of her blouse. “Are you looking for Shasa’s?”

She flinched and pulled back, but her eyes brightened at the word. “Maybe,” she said. “Someone told me there was a bar here where sailors wait for passengers?”

“That would be Shasa’s,” Tazir said. “Come on in—I’ll buy you a drink.”

She tried to link elbows with the girl, but the girl pulled away. Not surprising behavior in a rich kid like that, Tazir supposed—and judging by the feel of the silk, she was real rich.

“Oh. Uh, sorry, I—uh—” The girl flapped her mouth for a few moments like a fish in a net; her cheeks grew even darker.

“Don’t worry about it.” Tazir chuckled and tucked a stray braid back behind her ear. “I’m Tazir, by the way,” she said.

“I’m Shina.” The girl gave her a weak smile. Her eyes kept darting to the grimy shade of Shasa’s Bar, and her eyebrows kept getting higher and higher on her forehead. “Is that—”

“Only the finest dockside drinking pit in Humma,” Tazir said, gesturing toward Kodin and Chaqal with a flourish. “There you see my first mate and my quartermaster.”

“Are you here looking for passengers?” The girl stopped and looked Tazir in the eye, her brows arched.

Tazir cocked her head to one side and rubbed her neck. “Well,” she said, drawing the word out. “I mean, plenty of people come through looking for passage, but obviously we can’t just take anyone who—”

“What if it was someone, uh, really clean and quiet?” Shina clasped her hands together. Her eyes were darting between the bar, Tazir’s face, and the ground. “Who doesn’t eat much?”

“This someone you know?” Tazir said, raising one brow.

“I, uh.” The girl chewed on her cheek for a moment. “I was actually hoping to get passage myself,” she said. “I—well, it’s—”

Tazir looked the girl up and down, frowning just severely enough to make her afraid that someone was going to disapprove. Rich girls hated thinking that someone was going to disapprove of them—her marriage had at least taught her that much.

“Well,” she said after a few moments, “let’s discuss it.”

Shina nodded; a smile flickered across her face. “Thanks,” she said. As she followed Tazir beneath the canopy of Shasa’s, her shoulders curled in around her chest like a turtle’s shell. Her eyes were saucers, darting to all the thick, scarred faces in the shade.

“Hey-ey,” Chaqal said. “Keep your eyes down, girl.” She gave Tazir the steely, tight-mouthed glare that she swore she hadn’t practiced in a mirror. “What does she want?”

“Says she wants passage somewhere,” Tazir said. “Her name’s Shina.”

Shina swallowed, staring at the ground between her feet. She wore cheap, crudely made shoes—probably didn’t want to get her embroidered slippers all covered in poor dust. “My parents are making me get married to this cousin of mine,” she said. “I just can’t stand him, but they’re set on it.”

Tazir met Kodin’s eyes. Somebody had told this Shina girl what to say when she got to Shasa’s.

“All right,” Chaqal said. “They sending anybody after you?”

“I—I don’t know,” Shina said. “They might.”

Tazir and Kodin looked each other in the eye again. All things considered, it wasn’t unusual for a passenger to ask that they be ready to leave at any given moment. Depending on how dumb the passenger was, this could be a minor inconvenience or a major hazard.

“Where you planning on running to?” Chaqal asked.

“North.” For once, the girl sounded sure of something. “Doesn’t so much matter where in the north, just—I mean, I have a sister in Jepjep, so I need to see her, but north of Jepjep, at least—”

“We can do Jepjep,” Kodin said. “We can do north, too—we’ve been up as far as the long banks.”

“Pricey voyage,” Tazir pointed out. “Could take months.”

“I have plenty of money,” Shina said. “I’ll give you—”

“Hush, sweetheart,” Chaqal said. “This isn’t the place to go into detail about that kind of thing.”

It was too late. The girl’s voice had caught the attention of everyone in Shasa’s. Nobody got up yet, but eyes swiveled over to look at this gangly, awkward rich kid.

Tazir looked at Kodin again. One corner of his mouth twitched downward, and he took in a deep breath. There was no denying that this could be a risky job—dumb passenger, no plan, maybe being chased by someone. There was also no denying that this could be their last chance today to generate some cash.

Chaqal raised her hand and waited for the barkeep to acknowledge her. “Let’s talk about this some more out on the long docks,” she said to Shina with a sweet smile. “It would be wonderful to have someone my age on board for a while—sailing with these two grumps got old a while ago.”

The barkeep shuffled over with a tablet. “Two dakki,” he said to Chaqal.

“Got it,” she replied, reaching up beneath her linen tunic to get her coins from her purse. She dropped them in the barkeep’s waiting palm and hopped off her stool.

Tazir and Kodin followed suit. Shina followed them out of the bar, and would have stuck to the rear of the group if Chaqal hadn’t grabbed her by the wrist and shoved her forward.

“Be casual,” she said with another one of those practiced cheerful grins. “It’s a beautiful day, after all!” She wasn’t entirely blowing smoke on that one. The wind hadn’t yet been shut down in this part of the Jihiri Islands, and rolls of puffy white clouds gave the people a nice break from the sun now and then.

Shina opened her mouth, but then it dawned on her that she’d loudly told a bar full of big, crusty people that she was carrying plenty of money. She clamped her lips shut and picked up her pace. Behind them, the crowd was too thick to tell if anybody had followed them out of the bar.

“So,” Tazir said. “Where are you from?”

“Nijia,” the girl replied.

“Isn’t that down east?”

“It’s more south than east of here,” the girl said with a casual shrug. “My parents have some sugar fields.”

That took care of Tazir’s next question. She steered the girl a little to the right, over onto one of the seven docks that extended into the Bay of Humma. The Giggling Goat was moored out there a few hundred yards.

“When did you leave home?” asked Kodin.

“Four days ago—no, five,” Shina said. “They said I was going to start losing track of time.”

“Who said?”

“The sailors on the ship I took from Nijia,” she said. “They were nice—merchants, from Haresh.”

“Yeah?” Tazir asked. She cocked her head to one side. “What was wrong with their ship?”

“Their master doesn’t want them north of here,” Shina said. “He—I didn’t want to spend too much time talking to someone who might know my parents.”

“Fair enough,” Chaqal said.

That part of the story was probably more or less true. In Tazir’s experience, rich people all tended to know each other intimately so that they could hate each other more completely.

The crowd was thinning out now, a couple hundred feet offshore. The dock was getting thinner, too, but that didn’t stop the net repairers and fruit ice hawkers from setting up little boats full of wares they could sell to the sailors who were too hung over to make it all the way to the hub.

“How much money do you want?” Shina asked, finally hushing her voice. “I don’t want to be rude, but—”

“Depends on how far you want us to go.” Tazir pulled her pipe from a fold in the sash she wore around her waist.

“How far will you take me for forty thousand qyda?” Shina asked.

Tazir’s hand stopped in the middle of loading the pipe with tobacco. “What?”

“I have forty thousand qyda,” Shina said. “How far will it get me?”

Chaqal looked at Tazir. Tazir looked at Kodin. Kodin was grinning from ear to ear. Now, Tazir wasn’t the world’s best with exchange rates, but she remembered that a qyda was worth somewhere between six and ten dakki. Forty thousand was—was more money than she was going to see in one place ever again.

“That’ll get you to the long banks,” Kodin said. “Hell, if I’m in a good mood, it might even get you back.”

“So you’ll do it?” Shina said. “You’ll take me north?” Her eyebrows shot up her forehead, an excited grin tugging on the corners of her lips.

“Sure.” Chaqal laughed. “But don’t you want to see the boat first?”

Excerpted from The Drowning Eyes © Emily Foster, 2016

This excerpt first appeared on The Book Smugglers blog in November 2015