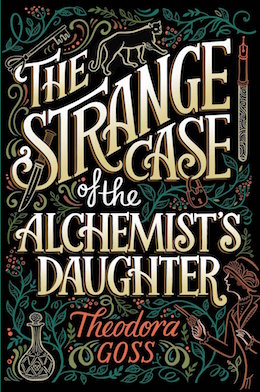

Based on some of literature’s horror and science fiction classics, Theodora Goss’s The Strange Case of the Alchemist’s Daughter is the story of a remarkable group of women who come together to solve the mystery of a series of gruesome murders—and the bigger mystery of their own origins. Available June 20th from Saga Press!

Mary Jekyll, alone and penniless following her parents’ death, is curious about the secrets of her father’s mysterious past. One clue in particular hints that Edward Hyde, her father’s former friend and a murderer, may be nearby, and there is a reward for information leading to his capture…a reward that would solve all of her immediate financial woes.

But her hunt leads her to Hyde’s daughter, Diana, a feral child left to be raised by nuns. With the assistance of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, Mary continues her search for the elusive Hyde, and soon befriends more women, all of whom have been created through terrifying experimentation: Beatrice Rappaccini, Catherine Moreau, and Justine Frankenstein.

When their investigations lead them to the discovery of a secret society of immoral and power-crazed scientists, the horrors of their past return. Now it is up to the monsters to finally triumph over the monstrous.

Chapter One

The Girl in the Mirror

Mary Jekyll stared down at her mother’s coffin.

“I am the resurrection and the life, saith the Lord.”

The rain had started again. Not a proper rain, but the dreary, interminable drizzle that meant spring in London.

“Put up your umbrella, my dear, or you’ll get wet,” said Mrs. Poole.

Mary put up her umbrella, without much caring whether she would get wet or not. There they all were, standing by a rectangular hole in the ground, in the gray churchyard of St. Marylebone. Reverend Whittaker, reading from the prayer book. Nurse Adams looking grim, but then didn’t she always? Cook wiping her nose with a handkerchief. Enid, the parlormaid, sobbing on Joseph’s shoulder. In part of her mind, the part that was used to paying bills and discussing the housekeeping with Mrs. Poole, Mary thought, I will have to speak to Enid about overfamiliarity with a footman. Alice, the scullery maid, was holding Mrs. Poole’s hand. She looked pale and solemn, but again, didn’t she always?

“Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord; even so saith the Spirit, for they rest from their labors.”

At the bottom of that rectangular hole was a coffin, and in that coffin lay her mother, in the blue silk wedding dress that matched the color of her eyes, forever closed now. When Mary and Mrs. Poole had put it on her, they realized how emaciated she had become over the last few weeks. Mary herself had combed her mother’s gray hair, still streaked with gold, and arranged it over the thin shoulders.

“For so thou didst ordain when thou createdst me, saying, dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return. All we go down to the dust; yet even at the grave we make our song: Alleluia.”

“Alleluia,” came the chorus, from Mrs. Poole, and Nurse Adams, and Cook, and Joseph, and Alice. Enid continued to sob.

“Alleluia,” said Mary a moment later, as though out of turn.

She handed her umbrella to Mrs. Poole, then took off her gloves. She knelt by the grave and scooped a handful of dirt, scattering it over the coffin. She could hear small pebbles hit, sharper than the soft patter of rain. That afternoon, the sexton would cover it properly and there would be only a mound, until the headstone arrived.

Ernestine Jekyll, Beloved Wife and Mother

Well, at least it was partly true.

She knelt for a moment longer, although she could feel water soaking through her skirt and stockings. Then she rose and reclaimed her umbrella. “Mrs. Poole, will you take everyone back to the house? I need to pay Reverend Whittaker.”

“Yes, miss,” said Mrs. Poole. “Although I don’t like to leave you alone…”

“Please, I’m sure Alice is hungry. I’ll be home soon, I promise.” She would follow Reverend Whittaker into the church and make a donation to the St. Marylebone Restoration Fund. But first she wanted to spend a moment alone with her mother. With what was left of Ernestine Jekyll, in a wooden box on which the raindrops were falling.

MARY: Is it really necessary to begin with the funeral? Can’t you begin with something else? Anyway, I thought you were supposed to start in the middle of the action—in medias res.

Before Mary could stop her, Diana crouched by the body of Molly Keane, getting blood on the hem of her dress and the toes of her boots. She reached across the murdered girl to the stiff hand that lay on her bosom and pried open the clenched fingers. From that cold grasp, she withdrew what the girl had been holding: a metal button.

“Diana!” cried Mary.

MARY: Not that in medias res! They won’t understand the story if you start like that.

CATHERINE: Then stop telling me how to write it.

It was no use standing there. It would accomplish nothing, and Mary needed to accomplish so much today. She looked at her watch: almost noon. She turned and walked under a gray arch, into the vestry of St. Marylebone to find Reverend Whittaker, who had preceded her inside. Ten pounds for the Church Restoration Fund… But she was Miss Jekyll, who had been baptized and confirmed at St. Marylebone. She could not give less.

She emerged from the quiet of St. Marylebone into the hurry and bustle of Marylebone Road, with its carriages and carts, the costermongers by the sides of the road, crying their wares. Although it was out of her way, she took a detour through Regent’s Park. Usually, a walk through the park could lift her spirits, but today the roses just starting to bloom were bowed down with rain, and even the ducks on the pond seemed out of sorts. By the time she reached the staid, respectable brick house at 11 Park Terrace where she had spent her entire life, she was tired and wet, despite her umbrella.

She let herself in, a procedure that would no doubt scandalize Mrs. Poole, and put her umbrella in the stand, then stopped in front of the hall mirror to take off her hat. There, she caught a glimpse of herself, and for a moment she stood, captured by her own reflection.

The face that stared back at her was pale, with dark circles under the eyes. Even her hair, ordinarily a middling brown, seemed pale this morning, as though washed out by the light that came through the narrow windows on either side of the front door. She looked like a corpse.

I have paused to show you Mary staring into the mirror because this is a story about monsters. All stories about monsters contain a scene in which the monster sees himself in a mirror. Remember Frankenstein’s monster, startled by his reflection in a forest pool? That is when he realizes his monstrousness.

MARY: I’m not a monster, and that book is a pack of lies. If Mrs. Shelley were here, I would slap her for all the trouble she caused.

DIANA: I’d like to see that!

“What are you going to do?” Mary asked the girl in the mirror.

“Don’t you start talking to yourself, miss,” said Mrs. Poole. Mary turned, startled. “It reminds me of your poor mother. Walking back and forth in that room of hers, until she near wore a hole in the carpet. Talking to who knows what.”

“Don’t worry, Mrs. Poole,” said Mary. “I have no intention of going mad, at least not today.”

“How you can joke about it, I don’t know! And her just in the ground,” said the housekeeper, shaking her head. “Would you like a cup of tea in the parlor? I’ve started a fire. Cook says lunch should be ready in half an hour. And there’s a letter for you, from Mr. Guest. I found it pushed through the slot when we arrived. I’ve put it on the tea table.”

From Mr. Guest, her mother’s solicitor. Well, hers now, although she did not think Mr. Guest would want to do business with her much longer. It had been different while her mother was alive.…

“Thank you, Mrs. Poole. Could you tell everyone to come into the parlor? Yes, even Alice. And could you bring—you know. I think it had best be done right away, don’t you?”

“If you say so, miss,” said Mrs. Poole, visibly reluctant. But there was nothing else to be done. Unless this letter from Mr. Guest… Could it possibly be about a change in her circumstances?

Mary went into the parlor, took the letter from the tea table, and tore open the envelope—neatly, but without searching for a letter opener. Perhaps… but no. If you could come to my offices at your earliest convenience, we can settle a few final matters concerning your late mother’s estate. That was all. She sat down on the sofa, stretching her hands to the fire. They were pale and thin, with the blue veins visible. She must have lost weight in the last few weeks, from worry and the long nights sitting by her mother’s bed so Nurse Adams could get some sleep. She wished she could lie down now, just for a moment. The funeral had been so… difficult. But no, what had to be done should be done as soon as possible. There was no point in putting it off.

“Here we are, miss,” said Nurse Adams, leading what reminded Mary of a procession from a fairy tale: the cook, the footman, the maid, and the poor little scullion in the rear. Mrs. Poole followed them in and stood by the door, with her hands folded and the expressionless face of a disapproving servant.

Well, this was it. How she hated to do it, but there was no alternative.

“Thank you all so very much for coming to the funeral,” Mary began. “And thank you also for your—your care and loyalty, particularly these last few weeks.” While Mrs. Jekyll had screamed and torn her hair, and refused to eat, and finally declined into her last illness. “I wish I were calling you in here simply to thank you, but I’m afraid there’s more. You see, I have to let you go, every one of you.”

Cook took off and wiped her spectacles. Enid sniffed and started crying into a large handkerchief that Joseph handed her. Alice looked like a scared rabbit.

How horrible this was! More horrible even than she had imagined. But Mary continued. “Before my mother’s death, I met with Mr. Guest, and he explained my financial position. Cook remembers, for she was here while my father was alive, but I don’t suppose the rest of you know.… My father was a wealthy man, but when he died fourteen years ago, we discovered that his fortune was gone. He had been selling his Bank of England securities and transferring the money to an account in Budapest. When Mr. Utterson, his solicitor at the time, contacted the Budapest bank, he was told that the account holder was not Dr. Jekyll, the bank had never heard of a Dr. Jekyll, and it was unable to supply information on one of its customers without an order from the Austro-Hungarian government. Mr. Utterson attempted to get such an order, but it proved impossible. The Austro-Hungarian government was not interested in a widowed mother and her child in far away London. I was only seven at the time, so I remember little of this. But as I grew older and my mother grew increasingly… well, unable to handle her finances, Mr. Utterson explained it to me. She had an income left to her by her father, which was enough to keep us all in modest comfort.”

She did not need to tell them how modest. No doubt they had noticed her economies, although she had tried to feed them well and keep them comfortable. To have meat on Sundays and coal in the cellar. But they must have noticed books disappearing from the library shelves, silver replaced with plate. Over the years, she had sold off china shepherdesses, and ormolu clocks, and all the silverware, including the epergne her mother had received as a wedding gift from the Archbishop of York. There were outlines on the walls where paintings had hung. Once, Enid had remarked that she was thankful there were fewer figurines to dust, then quickly said “Sorry, miss!” and scurried off to the kitchen. Her mother’s income had not been enough to cover the household expenses, and her medicines, and Nurse Adams.

“But it was only a life-income. When she died, it died with her. It does not come to me.”

For a moment, there was silence, broken only by the crackling of the fire.

“Then are you quite ruined, miss?” asked Enid, who indulged in romances of the cheapest sort.

“Well, I supposed you could put it that way,” said Mary. What a way of putting it! And yet it was true enough. She was, if not ruined, then nearly so. Her grandfather had died years ago, never dreaming that the provisions of his will would leave his granddaughter impoverished. He had been her last living relation—there was no one to whom she could turn. So that was it. Ruined was not, after all, such a bad choice of expression.

BEATRICE: The laws regarding female inheritance in this country are barbaric. Why should male heirs be left fortunes outright, while female heirs are left only an income for life? What if their husbands abandon them, as so many do? Or transfer their fortunes to accounts in Budapest? Who is to take care of their children?

DIANA: Oh bloody hell! If you let her get started, we’ll never hear the end of it.

“Mrs. Poole, if you would bring me the envelopes?” They had been locked in the housekeeper’s room since yesterday, when Mary had gone to the bank to withdraw … she did not want to think how much. Mrs. Poole pulled them out of an apron pocket and handed them to her. “In each of these envelopes is your fortnight’s pay, as well as a letter of reference for each of you. You need not stay the fortnight. As soon as you find other, and I hope better, employment, you are free to go, with my blessing. I am so very sorry.” She sat silently, looking at them, not knowing what else to say.

“Well, as for myself,” said Nurse Adams, the first to speak, “I must confess, Miss Jekyll, this has not caught me unprepared. I knew as soon as your mother started muttering about that face at the window. That’s how they start, if you’ll forgive my saying— seeing things that ain’t there. I thought, the poor woman won’t survive the month, and I was right. I always know these things! So I spoke to my agency, and there’s a position just opened up accompanying an elderly gentleman to the spas in Germany. I’ll be taking my leave tomorrow, if it’s all the same to you.”

“Yes, of course,” said Mary. “And thank you so very much, Nurse. The last few weeks were difficult for you, I know.” What would she have done without Nurse Adams? She and Mrs. Poole could not have held her mother down when she began screaming and crying about the face, the pale face… Even in her final days, when she was too weak to leave her bed, Mrs. Jekyll had whimpered about it in her sleep.

“As for me and Enid, miss,” said Joseph, “we didn’t want to tell you in the middle of your troubles, but we’re planning to wed. My brother is the proprietor of an inn in Basingstoke, and he has too much custom for one man to handle, so I’ll be going into business with him. And we’re hoping you’ll give us your blessing, like.”

“Why, that’s wonderful news,” said Mary. Thank goodness, for Enid’s sake, it had not merely been a dalliance. “I’m so pleased for you both. And Cook?” For Cook was the one she had really been worried about.

“Well, I’ll be honest with you, miss, I’d been hoping to stay on awhile yet,” said Cook. “But my sister’s been at me to come live with her, back in Yorkshire. Her husband died last year, and her daughters are grown and in service, so she’s all alone. Two old women living together—I’ll be bored to tears, without the hustle and bustle of London. Perhaps I’ll take up knitting! But I’m sorry to leave you in your troubles, miss. Having known you since you were a wee thing, and coming into my kitchen for jam tarts!”

“No, it’s I who am sorry,” said Mary. They were all being so kind, when here she was, telling them they no longer had a home. At least Alice could return to her family in the country. “You’ll be able to see your mother again,” she said to the scullery maid. “And your brothers, and that hen you miss so much, what was her name?” She smiled encouragingly, but Alice just kept twisting her hands in her apron.

When she had given them the envelopes and Mrs. Poole had ushered them downstairs to their lunch, all except Nurse Adams who asked for a tray in her room so she could start packing, Mary leaned back into the sofa and stared at the painting of her mother over the mantelpiece. Ernestine Jekyll, with her long, golden hair and eyes the color of cornflowers, smiled down at her in a way Mary could not remember her smiling while alive. Almost as long as Mary could remember, she had stayed in the large bedroom she had slept in since marrying Dr. Jekyll and moving to London from her native Yorkshire—pacing around the room, talking to invisible companions. Sometimes she scratched herself until she bled. Sometimes she tore out chunks of her hair, so it lay in long strands on the floor. Once, Nurse Adams had suggested she be sent to an institution for her own safety. Mary had refused, but in the last few weeks she had begun to wonder if she had been wrong. What had caused those violent spasms, those shrieks in the night? That final swift decline?

Even as a little girl, Mary had not cried easily. She had learned long ago that life was difficult. One had to live it with courage and common sense; it did not reward sentimentality. At the memory of her mother lying on her pillow, looking more peaceful than she had looked for years, Mary put her head in her hands. But she did not cry, as she had not cried at the funeral.

DIANA: Because our Mary never cries.

MRS. POOLE: Miss Mary is a lady. She does not throw fits, unlike some as I could name.

MARY: It’s not my fault I don’t cry. You know perfectly well it’s not.

CATHERINE: Yes, we know.

Mary’s “earliest convenience,” as Mr. Guest had put it in his letter, did not occur until a week later. First, there was Nurse Adams to see off, and Joseph and Enid, and finally Cook. One afternoon, Mrs. Poole came into the morning room where she was going through the accounts at her mother’s desk and said, “Alice is gone.”

“What?” said Mary. “What do you mean, gone?”

“I mean that she’s taken her things and gone off, without saying goodbye. She did all her morning work just as usual, without saying a word. I went into her room a minute ago, to tell her tea was ready, and there’s nothing there. Not that she had much, but it’s empty.”

“Well, no doubt her brothers came for her. Didn’t she say it was all arranged?”

“Yes, but she could at least have said goodbye. After the way I took her in and trained her. I never expected ingratitude, not from Alice! And no forwarding address. I would at least have liked to send her a card at Christmas.”

“She’s very young, Mrs. Poole. I’m sure you were thoughtless yourself when you were thirteen. No, come to think of it, I’m sure you weren’t. And I’m sorry about Alice. We’ll probably get a letter from her in the next few days, telling us she’s safely home and how nice it is to be back in the country. All right, I’m done here. It’s time to face Mr. Guest. It’s raining again. Could you bring my mackintosh?” She closed the account book and sighed. The last thing she wanted to do today was meet with the solicitor, but what had to be done should be done as soon as possible. Or so Miss Murray, her governess, had taught her.

Mrs. Poole met her in the hall, holding her mackintosh and umbrella. “I wish you would take a cab. You’ll be soaking wet, and when I think of you walking those streets alone…”

“You know I can’t afford a cab, and I’m just going to Cavendish Square. Anyway, this is the nineties. The most respectable ladies walk alone. Or ride their bicycles in the park!”

“And look like horrors,” said Mrs. Poole. “I hope you’re not thinking of wearing a divided skirt and getting on one of those contraptions!”

“Well, not today, at any rate. Do I look sufficiently respectable to your discerning eye?” Mary glanced at herself in the mirror and adjusted her hat, more out of habit than because it needed adjusting. She was not trying to look smart, and if she had been trying, it would not have worked anyway. Not when I look as though I’ve seen a ghost, she thought.

“You always look respectable, my dear,” said Mrs. Poole. “You’re a born lady.”

MRS. POOLE: Well, I never! I have never in my life called Miss Mary anything so disrespectful as “my dear.”

DIANA: Oh, stuff it! You do it all the time without noticing.

“A lady should be able to pay her butcher’s bill,” said Mary. Twelve pounds, five shillings, three pence: that was her current bank balance. She had written it neatly in the account book, and now she could not stop thinking about it. The number kept chiming in her head, like a clock always telling the same time. On her mother’s desk in the morning room was a stack of bills. She had no idea how she would pay them.

“Mr. Byles knows you’ll pay him eventually,” said Mrs. Poole. “Hasn’t he been supplying meat for this household since before your father died?”

“That was when there was a household to supply for.” Mary buttoned her mackintosh, picked up her purse from the hall table, then hooked the umbrella over her arm. “Mrs. Poole, you really should reconsider…”

“I’m not leaving you, miss,” said Mrs. Poole. “Not in this big house, all alone. My father was butler here under Dr. Jekyll, and my mother came from the country with Mrs. Jekyll. Your mother’s nurse, she was. Same as I was yours when you were in pinafores. This is my home.”

“But I have nothing to pay you with,” said Mary, hopelessly. “It was all I could do to give Cook and Joseph and the rest their fortnight’s wages. You can’t give me credit, like Mr. Byles. And a trained housekeeper could find another position, even at a time like this. I’m the one the employment offices don’t want. You should see these women, with their pursed faces, telling me I don’t know enough to be a governess—which is true—or that working in a shop ‘is not for the likes of you, miss’!”

“It certainly isn’t,” said Mrs. Poole.

“Or if I took a two-week typing course costing ten shillings, they might find something for me by and by. But I haven’t got ten shillings to spare, and I haven’t got two weeks! I called on Mr. Leventhal, but he says there’s no hope of selling this house, with the economic situation as it is. Unless, he says, a buyer comes along who will take on the expense of dividing it into flats.”

“Flats!” said Mrs. Poole in a horrified tone. “Divide a gentleman’s residence into flats! I don’t know what the world is coming to. Well, perhaps Mr. Guest will tell you something to your advantage.”

“That,” said Mary, “is highly unlikely.” She checked herself in the mirror again. Umbrella, mackintosh, gum boots. She was prepared for the deluge.

And a deluge it was. The rain beat mercilessly on her umbrella. In the gutters, rivers ran dark and fast. London went about its daily business: shops were open, carts rumbled down the streets, newspapers boys called out “Another ’orrible murder! Maid on her day out found without a ’ead! Read about it in the Daily Mail!” But the crossing-sweepers were soaked and glum, and the hansom cab horses shook their heads to get water out of their ears. The sidewalks thronged with umbrellas.

As though God has decided to drown the world again, she thought, almost wishing He would. Sometimes she thought the world needed drowning. But she pushed the uncharitable thought away and took a quick look at her watch to make sure she would be in time for her appointment. Her boots squelched on the wet pavement as she made her way through Marylebone.

Utterson & Guest, Solicitors, was located on one of the quiet, respectable streets near Cavendish Square. Mary knocked with the polished brass knocker. A clerk opened the heavy wooden door and led her down the long, paneled corridor to Mr. Guest’s office. While her mother was alive, Mr. Guest had come to the house, but the impoverished Miss Mary Jekyll was not important enough to warrant a visit.

Mr. Guest was as tall and lean and balding as ever. He reminded Mary of a cadaver; she imaged the paneled office, with its rows of leather-bound books, as the coffin in which he had been interred. He bowed over her hand and said, in his cadaverous voice, “Thank you for coming in response to my letter, Miss Jekyll. And in this rain, too!”

“I don’t suppose this has anything to do with my finances?” said Mary. She might as well be direct. He knew perfectly well that she had no money.

“No, no, I’m afraid your financial situation remains the same.” Mr. Guest shook his head regretfully, but Mary could detect a certain relish in his tone. “Do sit down, as our business may take some time. I asked you here because I received this.” Mr. Guest sat behind his desk and pulled forward a leather portfolio that had been lying beside the inkwell. “I was contacted by your mother’s bank—not the Bank of England, but another bank at which she had opened an account, some sort of cooperative society in Clerkenwell. Without my knowledge, I might add.” Clearly, he did not approve of his clients opening accounts without informing him, particularly in such a disreputable part of the city.

Mary stared at him in astonishment. “Another account? That’s impossible. Before she died, my mother had not left her room for many years.”

“Yes, of course,” said Mr. Guest. “But this account must have been opened before your mother… secluded herself entirely from the world.” In other words, went mad, thought Mary.

“When the account was set up, your mother deposited a certain sum, stipulating that each month, a portion of it would be paid to a designated recipient. When the director of the bank saw the notice of her death in The Times, he very properly contacted me. I requested that he send me whatever information he could, and a week later I received these documents. They include the account book.”

He unbuckled the portfolio, took out a book such as bank clerks use to keep their accounts in order, and placed it in front of Mary. She sat in the rather uncomfortable chair Mr. Guest provided for his clients, put her purse on her lap, and opened the book to the first page. At the top was written: DATE —TRANSACTION—AMOUNT—PURPOSE. Each transaction had taken place on the first of the month, and each was recorded in exactly the same way: Payment to the Society of St. Mary Magdalen—£1—For the care and keeping of Hyde.

Hyde! At the sight of that name, Mary gasped. It conjured an image from her childhood: her father’s friend, the man known as Edward Hyde—a pale, hairy, misshapen man, with a wicked leer that had sent a shiver up her spine.

MARY: That’s a bit melodramatic, isn’t it?

CATHERINE: Well, at any rate, he always made you feel uncomfortable. And he was insufferably rude.

“That account is now yours,” said Mr. Guest. “As you can see, it was originally set up with a single deposit of a hundred pounds. Since then, money has been withdrawn monthly, for some purpose I do not understand?” He paused for a moment in case Mary cared to explain. But even if she had any idea what this was about, she would not have enlightened the solicitor. He continued, “It contains the sum left after last month’s withdrawal: I believe the current total comes to twenty-three pounds. Not a large sum, I’m afraid.”

No, it was not, but Mary had a sudden vision of being able to pay the butcher, and the grocer, and of course Mrs. Poole. Perhaps they could even hire back Cook, who would not have to live with her sister in Yorkshire! And Mrs. Poole would not have to struggle with the oven, or producing edible meals from a cookery book she had never been trained to use. But no, that was too ambitious. Twenty-three pounds was significantly more than she had, but it was not enough to live on for any length of time—not at 11 Park Terrace. Still, some of the panic she had been feeling subsided. But the incredulity remained.

“For Hyde?” she said. “How could my mother possibly have been involved with Hyde? I was only a child, but I still remember the police coming to our house, questioning my father about him.”

“I was Mr. Utterson’s clerk at the time,” said Mr. Guest. “I remember the circumstances quite well, although fortunately I never met Mr. Hyde myself. That is of course why I asked you to come so urgently, although I hesitated to interrupt your period of mourning, Miss Jekyll.” He looked at her solemnly, but she thought that behind his professional mask, she could detect a smirk. He was the sort of man who would enjoy the misfortunes of others. “But there is more: your mother left these documents with the bank for safekeeping.”

He pushed the portfolio toward her. It was filled with papers of various sorts: another book, envelopes that likely contained letters, slips of paper that seemed to be receipts. She started to pull the other book out of the portfolio, but saw the look of avid curiosity on Mr. Guest’s face. He had probably restrained himself from looking through his client’s private papers, although he would have liked to. Well, whatever her mother had wanted to hide, Mary was not going to show him.

She closed and buckled the portfolio. “Thank you, Mr. Guest. Is that all?”

“Yes, that’s all,” he said, with a frown—of frustrated disappointment, thought Mary. “May I ask, Miss Jekyll, what you intend to do in this matter?”

“I shall close the account, of course,” said Mary. She would go to Clerkenwell—could one get there by omnibus?—and withdraw the remainder tomorrow. Thirty-five pounds, five shillings, three pence. She could not help thinking with relief of the new number.

“That is certainly the best course of action,” said Mr. Guest. “Whatever the account was created for, I suggest you have nothing more to do with it. And if I may also mention—young ladies in your situation often find it a relief to place their affairs in the hands of those who are more worldly, more wise in such matters. In short, Miss Jekyll, since you have recently come of age, you may choose to marry. A young lady of your personal attractions would certainly prove acceptable to a man who is not particular about his wife’s fortune.” Mr. Guest looked at her meaningfully.

Goodness, thought Mary. Surely he’s not proposing to me? She had an impulse to laugh, but after the events of the past week, it would come out sounding like hysteria. This had all been… a bit too much. “Thank you, Mr. Guest,” she said, rising and extending her hand. “I’m sure you’re very wise in worldly matters and all that. And I appreciate your advice. And could you please ask your clerk to fetch my umbrella and mackintosh?”

It was still raining when Mary emerged from the solicitor’s office. She walked back through the crowded city streets, carrying the portfolio under her arm so it, at least, would not get wet. By the time she reached home, she was tired, wet, and grateful that Mrs. Poole had already laid a fire in the parlor.

BEATRICE: Oh, your London rain! When I first came to London, I thought, I shall never see the sun again. It was so cold, and wet, and dismal! I missed Padua.

DIANA: If you don’t like it here, you can go back there. No one’s stopping you!

CATHERINE: Please keep your comments relevant to the story. And it is not my London rain. I dislike it as much as Beatrice.

Mary changed out of her black bombazine into an old day dress, put on a pair of slippers, and wrapped a shawl that had belonged to her mother around her shoulders. She lit the fire with a match from the box on the mantelpiece. How shabby the parlor looked! She had asked Mr. Mundy, of Mundy’s Furnishings and Bibelots, what else she could possibly sell, but he had shaken his head and said there was simply nothing left worth buying. Unless Miss Jekyll wanted to sell the fine portrait over the parlor fireplace? But Mary would not sell her mother’s portrait.

She sat on the sofa and pulled the tea table in front of her, then unbuckled the portfolio and pulled out the documents it contained. They would have been easier to sort through on her mother’s desk—she could not help thinking of it as her mother’s desk, although she had been using it for years to do the household accounts. But there was no fire laid in the morning room, and not much coal left in the cellar. Also, she did not want to face those bills again, not now.

The book was, more properly, a notebook: her father’s laboratory notebook, she realized when she began leafing through it. She recognized his handwriting, the same angular hand that had commented in the margins of his books. The envelopes were addressed to Dr. Henry Jekyll, 11 Park Terrace. They must contain letters sent to him while he was alive, perhaps about his scientific experiments? He had maintained a large correspondence with other scientists in England and Europe. Scattered among the envelopes were miscellaneous receipts, mostly from Maw & Sons, the company that had supplied the chemicals for his experiments. She began to sort through the documents, barely noticing when Mrs. Poole brought in her dinner of a chop with peas and potatoes. She moved the documents to the sofa so Mrs. Poole could set it on the table, thanking the housekeeper absentmindedly.

When Mrs. Poole came to clear away, she leaned back into the sofa and said, “You know, I think Mr. Guest almost proposed to me today? Or hinted that I should marry a man who could take charge of my affairs, since young ladies are so unworldly.”

“And you running this house since you were old enough to sign your mother’s name!” said Mrs. Poole. “I’ve never held with men, and that’s a fact. Footmen are ornamental in white stockings for dinner service, but not as useful as a good scullery maid. Although Joseph made himself useful enough, I’ll admit.”

“If only I could afford a good scullery maid!” said Mary. “I hated letting Alice go, but she’s better off with her family. Mrs. Poole, could you sit down for a moment? I know, I know, it’s not your place. But please, there’s something I need to ask you.”

Reluctantly, Mrs. Poole sat in one of the armchairs by the fire, with her hands folded on her lap, as though she were sitting in one of the pews of St. Marylebone. “Well, miss?”

Mary leaned forward and stared into the fire. She did not quite know how to ask… but directly was always best. She turned to Mrs. Poole and said, “What do you remember about Edward Hyde?”

AUTHOR’S NOTE: I can’t tell you how much I regret allowing Mary and the rest of them to see this manuscript while I was writing it. First they started commenting on what I had written, and then they insisted I make changes in response to their comments. Well, I’m not going to. I’m going to leave their comments in the narrative itself. You, dear reader, will be able to see how annoying and nonsensical most of them are, while offering the occasional flash of insight into character. It will be a new way of writing a novel, and why not? This is the 90s, as Mary pointed out. It’s time we developed new ways of writing for the new century. We are no longer in the age of Charles Dickens or George Eliot, after all. We are modern. And, of course, monstrous…

© 2017 by Theodora Goss, reprinted with permission from Saga Press.

Looks like fun! But is it Catharine or Catherine?

It’s definitely Catherine! I caught that too, and it’s being fixed. :) I don’t think I’m giving anything away when I write that it’s actually an anagram: cat-in-here . . .

I’ve been waiting for this ever since I read “The Mad Scientist’s Daughter”. Thank you for writing another story about these women. Is it too soon to ask when the next one is coming out??

I’m glad you liked that story! :) For anyone who hasn’t read it, I’ll post a link: http://strangehorizons.com/fiction/the-mad-scientists-daughter-part-1-of-2/.

The sequel is scheduled to come out in the summer of 2018. I’m currently trying to finish it, and I’ve gotten stuck in a tricky scene. The second book is longer and involved a lot more research, because Mary, Diana, Beatrice, Catherine, and Justine travel to the Austro-Hungarian empire . . . But I won’t say any more for now!

Well, the excerpt has done it’s job, in that I really want to read the rest now.

That said, this feels like a ‘slow burn’ sort of story to me. Like I’m watching the smoldering attempts at a fire, poking at it somewhat frustratedly with a stick every time I turn a page. “Why won’t you catch?”

I want to read more but I feel like the pacing would turn me off if it didn’t pick up soon, is what I guess I’m getting at.

I definitely want this book on my bookshelf.