In the enchanted kingdom of Brooklyn, the fashionable people put on cute shoes, go to parties in warehouses, drink on rooftops at sunset, and tell themselves they’ve arrived. A whole lot of Brooklyn is like that now—but not Vassa’s working-class neighborhood.

In Vassa’s neighborhood, where she lives with her stepmother and bickering stepsisters, one might stumble onto magic, but stumbling out again could become an issue. Babs Yagg, the owner of the local convenience store, has a policy of beheading shoplifters—and sometimes innocent shoppers as well. So when Vassa’s stepsister sends her out for light bulbs in the middle of night, she knows it could easily become a suicide mission.

But Vassa has a bit of luck hidden in her pocket, a gift from her dead mother. Erg is a tough-talking wooden doll with sticky fingers, a bottomless stomach, and a ferocious cunning. With Erg’s help, Vassa just might be able to break the witch’s curse and free her Brooklyn neighborhood. But Babs won’t be playing fair….

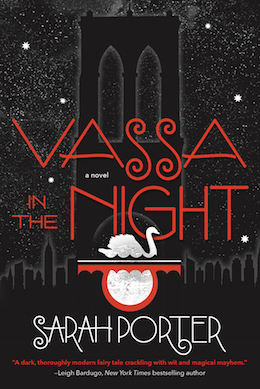

Inspired by the Russian folktale “Vassilissa the Beautiful”, author Sarah Porter weaves a dark yet hopeful tale about a young girl’s search for home, love, and belonging—Vassa in the Night is available September 20th from Tor Teen!

Chapter 3

There’s plenty of nothing in Brooklyn, but BY’s still hogs vacant space as if it was afraid of getting emptiness deprivation sickness. Not many stores in the city have parking lots but our local BY’s franchise is surrounded by a field of dead cement that takes up a whole small block, though cars never seem to park there. As I get close the stench is like sick sweet fur in my nostrils, and I try not to look—but who can keep from looking at that? The parking lot is ringed in by poles maybe thirty feet high, and on top of every pole a severed head stares down, some with eyes and some with just gutted pits. A few heads are fresh and still have humanish colors, just a little too gray or too white. With my weird pallor I’ll fit right in, I guess. Others have mossy patinas, verdigris mold, or purplish pockets of rot. I don’t want to recognize Joel, but I do. He’s spiked to my left and it looks like he’s staring off at the sky, dreaming of bleeding into the moonlight. His smooth black skin has gone ashy and sort of prickly, as if it’s covered in iron filings. I acknowledge that many intelligent people would say I’m exhibiting poor judgment, doing something so dangerous out of pride and rage, and, I mean, no doubt. But somehow looking at Joel gives me my first little shiver of hope that maybe I will go home tonight and fling the lightbulbs straight into Stephanie’s face. With any luck they’ll explode and engulf her in snow-white flames.

It’s only logical: BY’s can’t kill everyone who shops there. If they did, they’d go out of business.

At the center of the ring of poles, BY’s dances. Just like in the ads, the building hops and swivels on giant chicken feet, on yellow legs that manage to be at once wobbly and graceful. Its orange plastic sides glow with this relentless singeing shine that hurts to look at, and the beams lancing out of its plate-glass windows bow and scrape across the pavement. As if they were searchlights. Always looking for someone. The orange building bends with a dramatic forward swoop, a distorted trapezoid of light lunges toward my feet, and then I see that not every pole has its own personal head on top.

No: there’s exactly one that is empty.

Nice touch, I’d like to say. Good one.

There’s a growling sound that rises and falls; I’ve been hearing it for a while but not really paying attention. Now the source of it lashes by and I jump back so it won’t crush my feet: a motorcycle, jet black, with a heavy-muscled, black-clad rider. His helmet is strangely huge, protruding like a spherical cancer from his skull, and his visor is down. He looks like a concentrated chunk of the darkness, a clot in the night’s black blood. He’s going fast enough that I don’t have time to see much, but when he comes around again I try to make out his face. All I can see is a mouth with thin, gray-pink lips above a boulder of a chin. “Hey!” I call, but he’s off .

I watch him for a few more minutes, his engine snarling up and down in pitch like somebody practicing scales on a dog. He’s going around. And around. Twice more I try to talk to him, but it’s like he can’t hear me or doesn’t care. His head never turns and his visor looks completely opaque, and much blacker than the sky with its haze of outcast light. The guy must be some kind of security guard, but it seems like he’d be more useful if he could see.

I start to realize I’m stalling. BY’s prances on its horned legs, but, like every city kid on the East Coast, I know just what to do to make it stop.

The next time the motorcycle burns past I step through into the circle of those watching heads, and now the engine whines by behind me. So my muscles are tight and my legs are trembling and I feel sick and cold and stupid. Why should I care?

“Turn around,” I sing. My voice comes out thin and crackly. “Turn around and stand like Momma placed you! Face me, face me!”

The building stops spinning abruptly, with a little jerk. Then, quite deliberately, it rotates so the plate-glass windows and the door are pointing my way. I could swear it’s looking at me. They’re just windows, obviously nothing but mindless glass, but somehow I can’t shake the sense of a cynical expression and even a tweaky little smirk like the one on Stephanie’s face when she sent me out to die.

Then the chicken legs crease at the knee and the whole store drops, bending forward to invite me in. I will go right in, get the lightbulbs, and leave. I will…

But there’s something I have to do first. Knowing what I know about Erg’s proclivities, bringing her into a BY’s seems like absolute suicide. I don’t want to leave her lying on the pavement, though. I look around for somewhere to hide her until I’m done in there. For no good reason there’s a tree stump right in the middle of a parking space, and when I walk closer and peer down I see a deep cleft in the wood, big enough for Erg if I stuff her. She might have to go in headfirst, but it can’t be helped.

She’s howling like a siren from the instant I reach into my pocket. “No! Vassa! No, you can’t do that! Stop having such bad ideas! You can’t leave me!”

“Erg,” I say. “You have a truly crappy track record with the impulse control. I can’t trust you not to get me killed. That makes sense, right?”

“Your mom didn’t say anything about cramming me into stumps, Vassa! Do you think she was an idiot? How could you even think about…” Erg can’t talk anymore. She’s sobbing, her little painted face all crimped and deformed. It’s incredible that something so small can make such a racket. Maybe the noise is her way of compensating for her inability to produce tears.

Behind me BY’s shuffles impatiently, scratching the black cement with backward strokes of its knobbly three-toed feet. “Erg.” I sigh. I don’t like to see her crying like this. “Erg, I’ll be right back, okay?”

Erg gags, although she has no breath and no throat to do her choking with. “You cannot go in there without me, Vassa! You cannot do this. Bad things will happen if I’m not with you in there. You can’t!”

BY’s starts pitching and shaking. I can tell it’s getting bored. I hold Erg up and look into her blue blob eyes, trying to see through the paint to whatever is back there. “Erg, listen to me, you have to promise…”

“I already did!” Erg sniffs. “I told you everything will be fine! We just have to stay together!” BY’s door lifts a foot off the ground; it’s getting ready to rear up again. I look from that deep crevice in the wood to Erg’s eager face, then to the slowly ascending door. I could just give up on the whole lunatic plan. The empty street beckons, commas of amber light shining on the windshields of the sleeping cars.

And then I’m suddenly running: away from the street, toward that drowsily floating glass door. It’s swinging open, clapping back and forth although there’s no real wind, at least a yard above the ground now and rising fast. Erg is still clutched in my hand. It’s madness, but I leap and land sprawled inside the open doorway with my legs dangling out into the night.

I can feel myself sailing up, and up.

Only now does it occur to me to wonder if singing the jingle works when you’re inside the store? Or, um, only outside? The store cants abruptly so that the floor in front of me is sloping down instead of up and then gives a little jump. I’m jolted free of the sill and I go skimming across slippery linoleum until my head collides with a display of laundry detergent. As soon as I catch my breath I stuff Erg back into my pocket; keeping her hidden is practically a reflex at this point, but now I catch myself wondering if someone will think I’m stealing her.

Nothing happens, though. The floor settles so it’s reasonably parallel to the ground and I haul myself to my feet, gaping. I expect to see horrors, hooks with dripping human hearts or something. En.trails looped around the barbecue sauce. But no: it looks like any other convenience store in Brooklyn, only much brighter and neater. The floors are neon yellow and so clean it’s like they’re screaming at me. The back wall is covered in the usual tall refrigerators with sliding glass doors, and then there are graded racks of candy bars, and bristling bags of chips, and orderly rows of shelves full of soup and toilet paper. Coffee and magazines and hot dogs under a glaring orange heat lamp. The same old whatever. The same assorted nothingness, now available in a pack of five tropical flavors.

I can’t imagine what I was so afraid of. Pop music is playing very softly. I don’t recognize the song but it’s pretty, a girl’s voice lilting over piano. It doesn’t seem like there’s anyone here but me until I turn around. A sweet-looking old lady is fast asleep at the register, her head resting on crossed arms. She’s wearing a faded black dress with blotchy flowers and her pink scalp shows through wisps of pearly hair stuck full of so many bobby pins that they cover more of her head than her hair does. She looks way too old to have a job and I can’t help feeling sorry for her. At her age she should be home in bed, not working the night shift in a sickeningly cheery place like this. I’m going to feel like a real bitch, waking her up so I can check out.

She snuffles a little and mutters in her sleep. Yellowish slime clumps in her snowy lashes. Deep in my pocket Erg is very still, but I can tell by her tension against my fingers that she’s awake and alert.

None of the aisles are labeled, I notice. But the lightbulbs shouldn’t be too hard to find. I head up one row that looks to be full of cleaning supplies. With a lurch the store starts dancing again. The stuff on the shelves must be tacked down somehow because nothing falls. Everything just pitches together, linked in the same clattery rhythm. It seems like we’re dancing to that song on the radio, which is still playing as if it had just started over again.

Maybe it’s the swaying, but I’m finding it hard to focus. I see the brand names honking out of their Day-Glo spirals, and just looking at them makes me feel like some kind of acrid smoke is in my eyes. Up ahead there’s a blue block that looks like the packaging on our usual lightbulbs, but when I get there it’s something else, some strange Lithuanian cookies maybe.

Fine. The store’s not that big. I turn down the next aisle, all Ritz crackers and pinkish pastes in jars, strawberry marshmallow butter and foamed brie with the legend It’s Artisanal! in flowery script. Under the music I hear a very soft noise, this rubbery scuffling. It’s hard to believe when the place is so spotless that every surface looks lit by fever, but I guess they must have mice in here. It doesn’t seem like lightbulbs would belong in this aisle, but apparently BY’s isn’t as immaculately organized as I thought. A stack of those familiar blue boxes is visible at the very end, on the left.

I could almost think the mice were following me. The moist whispery sound stays just behind my right shoulder as I move in on the lightbulbs. I’m starting to think that it sounds more like something dragging than like sharp-clawed little feet, but the noise is so quiet I can’t be sure. Maybe it’s the sound the boxes make as the floor rocks?

Those blue boxes aren’t lightbulbs, either, but some kind of knock-off Pop-Tarts in a flavor called lagoon. For a moment I just stand there, trying to imagine what lagoon filling would taste like. The colors on the packaging are making my eyes water and burn. My lids flutter. Maybe I’m imagining things, but somewhere behind my right shoulder I hear what I could swear was a quick, spongy hop.

I might be more on edge than I like to admit, because I swing around the display at the end pretty quickly. The old lady at the register has started snoring in this feathery way, tiny ruffling snortlettes. She’s obviously way too skinny and frail to chop anybody’s head off . There’s nothing to worry about, except perhaps for getting down, and I suppose the brawny gentleman on the motorbike.

There aren’t that many more aisles to check, though, and the bulbs have to be somewhere. I hope I have enough money to get Chelsea her ice cream, too. There are more blue boxes in this aisle, and I feel like I’m starting to notice a pattern: they’re always at the end, always on the left. I’m learning to be wary of fake outs and I practically run up to them, trying to catch them before they change. They do, of course. This time they resolve into cans of blue soup.

The noise on my right shuffles faster, and a little louder. Suddenly it’s very obvious that whatever is there is trying to catch up. I shift back a little, looking off at nothing, and then spin around and grab a package of toilet paper standing in front of the source of the noise. I have just enough time to see a blur of something pale dropping down to the shelf below. A light flapping and smacking, and it’s gone.

It’s real, and it is not a mouse. Too big. A shade too pink.

Since I’m at the back of the store I decide to just check one last aisle, fast, and then get out of here. I’ll wake up the old lady and buy something small, a pack of gum or a magazine. And then I think I’m never going home again.

This time I hear the sliding, shuffling noise on both sides. My heart is pattering at an absurd clip now. There are two of those things, and they’re trying to make sure—of what, exactly? There’s a sudden aggressive scratching on my left and I instinctively lurch right, brushing against a shelf and almost losing my balance. I let out a yelp of surprise. In my right pocket Erg kicks violently—she must bruise my hip—and then there’s a thud and rumble as something falls to the yellow floor.

A candy bar in a scarlet wrapper. And on top of the candy bar there’s a human hand with no body attached, rolling back and forth and slamming loudly against the metal shelf with a noise like a muffled gong.

The hand is big-boned and long-fingered. Bulging veins like indigo snakes that have gorged on too many rats. And there’s an oily mauve tinge to its skin.

The tip of its thumb shows the deep red print of tiny teeth. I lift Erg from my pocket for an instant, staring in bewilderment. A trickle of blood slips from her dainty ruby mouth, and she motions frantically at my pocket for me to put her back.

As soon as I do the old lady is standing there, looking at me with wide, pitying eyes.

Something has a hold of my hair, wrenching a huge hank of it up behind me. Something strong. On the floor the wounded hand starts springing up and down, one accusing forefinger pointing my way. Its nails are painted with emerald glitter.

“Oh, little one,” the old lady whispers mournfully, “you were stealing. Weren’t you?”

It’s funny but it takes me a moment to realize I’m the one she’s accusing. “I was not! I think that sick thing on your floor was stealing. It was flopping all over that candy bar like some kind of squashed fish.”

The hand’s fingers all jerk straight at once and it spasms with indignation, then points at me again.

“He can’t steal,” the woman reproves me. One of her irises is completely veiled in some gray-white, sticky web of disease. “He works here. Keeping the shelves tidy, cleaning… I don’t think you young people understand how much harm your thieving does. I’m all alone, and my store here is all I have. I hope you realize now that what you did was very wrong.”

I try to move, and the thing behind me jerks my head back so hard that the skin of my throat strains. In front of me the wounded hand bounces excitedly, then takes off scampering down the aisle with a weird grabbing motion.

I have an awful sense of what it might be going to fetch.

“I was not stealing!” I’m yelling now. “I didn’t take anything!” The hand reappears behind her, hopping along more slowly with a heavy axe swinging awkwardly in its grip.

“You must have been,” she mutters. “That’s why he was pointing you out. You could at least say you’re sorry.” The hand has begun climbing the shelves at her side, mashing the steel support between three undulating fingers and its palm while the axe sways between thumb and forefinger. The blade is curved and mirrored, reflecting bags of white bread as it creeps upward. It smacks against the shelves with a dull, recurrent clank. The blood in my head is buzzing and my legs start to go slack. That nasty fleshy spider has climbed almost high enough to—

“I’ll empty my pockets!” I scream. Erg kicks me. “Really! How could I be stealing, when I don’t have anything of yours?”

It’s pathetic to realize that those are probably my last words. I’m most ashamed at the thought of what this will do to Chelsea and how she’ll blame herself. The hand reaches the top shelf and swishes the blade triumphantly upright.

The old lady sighs. “No,” she tells the hand. “She’s not wrong.”

The hand jumps in protest and knocks a pile of cereal boxes off the shelf.

“There are rules,” she mutters. “Rules for everybody. Always rules. The candy would have to be on her person somewhere for it to really count. There’s too much… ambiguity. You’d be getting us into difficulties with the fussy types, the sticklers and quibblers, wouldn’t you? There’s an element of doubt.”

The hand drops the axe with a clunk. The falling blade slices a box of sugared flakes wide open and they rustle onto the floor.

“There’s a lot more than doubt,” I snarl. Now that I’m not seconds away from being butchered I’m ready to spit at her. “You’d better let me go, now!”

She levels her eyes at me, one gray and one veiled. The problem with staring back at her is that I start to get the sense that her sick eye is orbiting like a dead planet, and that my head is its sun.

“Not that much doubt,” she whispers. The blotchy pink and yellow flowers on her dress look like bacteria creeping in a petri dish. “Not nearly that much. He pointed at you, after all. It’s part of his job to defend my property, and I trust his word over yours. No, you won’t be… leaving immediately.”

The hand flings itself petulantly off the shelf and starts corralling spilled cereal with little sideways swipes. It’s funny that something with no face can look so mad.

I’d like to tell her she’s wrong. But that whatever-it-is still has an iron grip on my hair—I can’t see it, but it must be the other hand. My scalp is stretched and stinging and I can barely twitch my head. Even if I could shake the hand off we’re far enough above the ground that I’d at least break a leg if I jumped. And then there’s the guy on the black motorcycle, ready to run me down as I try to hobble away. My odds of escape are notably poor. I’m trying to think of some alternative to screaming insults when she lets out a dreamy hiss.

“Enough doubt, I’d say, for a chance. I’ll give you an opportunity to demonstrate your virtuous character. Show me that I should believe you instead of an old and dear subordinate. A chance to work off your debt to me, shall we say.”

“This is insane!” I manage. My voice sounds garbled. “What do you think I owe you?”

When she stares at me it’s her veiled eye, the one with no pupil, which seems to zoom in on my face. “More than you owe yourself. More than to mother or father. A possibility of life repossessed from the muck you’ve made of it. You should be grateful.” She tilts her head and that web in her eye seems to drape itself over me, gummy threads feeling the shape of what it can’t see. “You’re pretty. Having you here will be good for business.”

Erg is stroking my hip through the layers of fabric. It’s clear what the gesture means: Calm down, Vassa. Just be cool and play along. We’ll figure something out. It almost makes me angrier, but since Erg did just save my life—at least for now—I throttle my impulse to tell this old ghoul to go drink bleach. “What do you have in mind, then?”

“Three nights. Three. Do what you’re told, show yourself mature and responsible… Why did you come here to night?”

Her voice rasps through my head. The same song is still playing, sprinkling mournful piano notes over the air. “I was just picking up lightbulbs.”

She starts nodding. “I’ll throw those in. A commitment of three nights; your pay will be your survival. And a package of lightbulbs. Two packages, if you like.” She isn’t even looking at me anymore; she could almost be dreaming on her feet, her words coming out half song and half wind. “Three nights. You can work the register. Then I can sleep. I never get to sleep.”

“You were sleeping when I came in,” I point out. I don’t think it will do any good to mention that three nights could be an extremely long time.

“I was not. I was working. There is always the minor maintenance to be done, the repairs to the twiddly bits at the fringes. If I were only less fastidious…” She’s already turning away, shuffling back the way she came. “I don’t think you deserve a name. I don’t see how a callow little vixen like you could have earned a name. But I suppose your foolish parents disregarded that and gave you one anyway?”

It’s wrong to slap old ladies sideways, and then this one commands a pair of evil hands that are just dying to lop my head off . The hand behind me drops down, still dangling in my hair like some gross prehensile starfish, and shoves me between my shoulder blades to make me follow her. It’s hard to believe a hand could be so strong with no body attached, but I still stagger from the impact. “I’m Vassa.”

“Vassa,” she whispers lethargically. “Vassa, my imp. You may call me Babs. We have a deal, then? Three nights?”

“Fine,” I say. There’s not much else I can do at the moment. The hands herd me up to the counter, thumping at my back and prodding my ankles. I swing my hair, trying to dislodge that hideous clinging paw, and it punches my ribs to retaliate. I’m dragged around to the back of the counter then jabbed by glitter-slicked nails until I sit down in the chair Babs vacated to come after me. Torn mustard stuffing shows through shredded upholstery. Unlike everything else in the store the chair is filthy, its cushions the color and consistency of soot-crusted oatmeal.

“You can start,” Babs wheezes, “tonight. Be careful you don’t make mistakes when you’re counting out change. I’ll expect the balance in the register to be exact. Otherwise, we’ll have to attend to you. A reliable numerical sense is the first foundation of the mind. It lets you count the seconds you have left. It adds rigor, little one. And you seem… shaky.”

At least the hands have finally stopped grappling at me. They’re balancing on their wrist-stumps on the counter, palms facing inward and their fingertips curling. Those green-spangled nails seem to watch me like a row of quizzical eyes. Their postures are perfectly matched. “Got it,” I tell Babs absently. Once she’s asleep and the hands are off patrolling I can wait for the next sucker to arrive and sing the jingle, coax the store down to the ground again. Then I’ll just have the motorcyclist to deal with.

“That’s nice to hear,” Babs says. “I’ll be asleep in the back.” She turns to leave, her hand on a narrow door in the corner. Erg pokes me. A reminder.

“What if I get hungry?” I ask.

“Oh… You can eat what you like while you’re here. Just don’t take anything out of my store. You understand.” She glances lazily at the hands. “Dismissed, you two. Back to your duties.”

And then they’re gone, and I’m in a chair that wobbles with each hop and twirl of the floor below me. The first thing I do is take out my phone; I need to tell Chelsea I’m okay. The phone is dead, though, and I feel like I should have known it would be. There’s nothing I can do but sigh and stuff it back in my pocket.

Almost the entire wall to my right is made of glass and in it the city dances with manic enthusiasm, the houses and stores rushing up and down as if all those glowing windows were caught in a dark tide. The light projecting from BY’s waves like a flag across the parking lot, sometimes catching one of those skewered heads and making it shine: dead women and men becoming moons in my personal night. When Babs told me I owe her more than I owe myself, I thought that more than nothing might not amount to much. Now Joel’s head bounces by, gazing with blank rotten rapture through the glass, and I want to ask him: What do I owe myself, Joel? What did I borrow from myself, and how on earth will I ever give it back?

Excerpted from Vassa in the Night © Sarah Porter, 2016