Wren owes everything she has to her hometown, Hollow’s End, a centuries-old, picture-perfect slice of America.

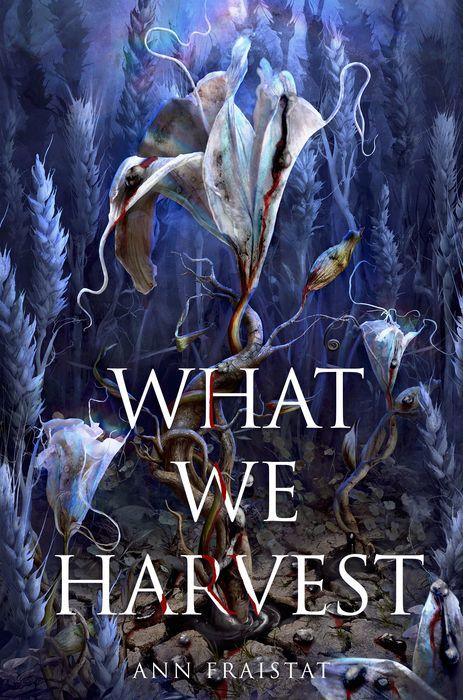

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from What We Harvest by Ann Fraistat, out from Delacorte Press on March 15.

Wren owes everything she has to her hometown, Hollow’s End, a centuries-old, picture-perfect slice of America. Tourists travel miles to marvel at its miracle crops, including the shimmering, iridescent wheat of Wren’s family’s farm. At least, they did. Until five months ago.

That’s when the Quicksilver blight first surfaced, poisoning the farms of Hollow’s End one by one. It began by consuming the crops, thick silver sludge bleeding from the earth. Next were the animals. Infected livestock and wild creatures staggered off into the woods by day—only to return at night, their eyes fogged white, leering from the trees.

Then the blight came for the neighbors.

Wren is among the last locals standing, and the blight has finally come for her, too. Now the only one she can turn to is her ex, Derek, the last person she wants to call. They haven’t spoken in months, but Wren and Derek still have one thing in common: Hollow’s End means everything to them. Only, there’s much they don’t know about their hometown and its celebrated miracle crops. And they’re about to discover that miracles aren’t free.

Their ancestors have an awful lot to pay for, and Wren and Derek are the only ones left to settle old debts.

CHAPTER 1

So, it had finally come to kill us, too.

The sickest part was, I’d started to believe we were invincible—that somehow the miracle of our farm might protect us. I’d seen Rainbow Fields survive crackling lightning, hail, devouring armyworms, eyespot fungus. No matter what came from sky or earth, the field behind our house still swayed with towering, iridescent wheat. Crimson, orange, yellow, all the way to my favorite, twilight-blazed violet: each section winked with its own sheen.

My whole life, the wheat had soothed me to sleep through my bedroom window with its rustling whispers, sweeter than any lullaby, or at least any my mom knew.

My whole life, until now. When I realized even rainbows could rot.

I stood at the very back of our field. A gust of wind caught my hair, and the cascading waves of wheat flickered into a rainbow, then stilled back into a field of shivering white gold. At my feet, a sickly ooze crept from their roots. It wound up their shafts and dripped from their tips.

Buy the Book

What We Harvest

The quicksilver blight, we called it, because it gleamed like molten metal. But the stench gave it away for what it really was—a greedy, hungry rot.

So far, I’d only spotted six plants that had fallen victim. No surprise they were at the back of the field, closest to the forest.

The blight in those woods had crept toward us for months, devouring our neighbors’ crops and pets and livestock. Our neighbors themselves. Every night, the grim white eyes rose like restless stars, watching us from behind the silver-slicked trees.

The air hung around me, damp—cold for late June in Hollow’s End. Spring never came this year, let alone summer. Even now, the forest loomed twisted and bare. From where I stood with our wheat, I could see streaks of blight glinting behind decaying patches of bark.

My breaths came in tiny sips. If I closed my eyes, if I stopped breathing, could I pretend even for a second that none of this was real?

The field was hauntingly quiet. Wheat brushing against wheat. The farmhands had packed up and fled weeks ago— like most of the shop owners, like most everyone in Hollow’s End except the core founding families—before the quarantine sealed us off from the rest of the world. In the distance, our farmhouse stood dark. Even Mom and Dad were out, off helping the Harrises fight the blight on their farm. They had no idea our own wheat was bleeding into the dirt.

Dad had tried to keep me plenty busy while they were away, tasking me with clearing out brambles near the shed. He and Mom didn’t want me anywhere near the back of our field, so close to the infected forest. But today, they weren’t here to check for crop contamination themselves— and they also weren’t here to stop me.

I was our last line of defense. The least I could do was act like it.

Hands gloved for protection, I grabbed the nearest stalk and heaved it up from the festering soil. I could barely stand to hoist it in the air, its suffocating roots gasping for earth. But this plant was already good as dead. Worse. It would kill everything around it, too.

Even me, if I wasn’t wearing gloves.

As I ripped up plant after plant, the stench, syrupy like rotting fruit, crawled down my throat. I hurled the stems into the forest and spat after them.

The wind answered, carrying a distant tickling laugh that squirmed into my ear.

I froze, peering into the mouth of the forest—for anything that might lurch out, to grab me or bite me or worse.

Only silent trees stared back. I must’ve imagined it.

The blighted didn’t wake until nightfall, anyway, and the sun was still high in the sky. Maybe two o’clock. I had time to deal with our infected wheat, before my parents raced back from the Harrises’ in time to meet the town curfew at sundown. Before the blighted came out.

Not a lot of time. But some.

Mildew stirred in my sinuses, like it was actually under the skin of my face. A part of me.

A sour taste curdled behind my teeth.

I spat again and turned to kick the dislodged earth away from our healthy wheat. My foot slipped—on a patch of glistening blight. The puddle splashed into tiny beads, like mercury spilled from a broken old-fashioned thermometer. Shifting, oily silver dots.

My stomach dropped. No. Oh no, oh no.

It wasn’t just in the plants. It was in the soil. How deep did it already run?

I needed a shovel.

I threw off my contaminated gloves, kicked off my contaminated shoes, and ran. Dirt dampened my socks with every pounding step down the path to our shed. Seven generations of blood, sweat, and toil had dripped from my family into this soil. That was the price we paid to tame this patch of land—our farm. Our home.

That wheat was everything we had.

As long as I could remember, my parents had sniped at each other over our thin savings. With my senior year looming ahead this fall, their fighting had kicked into overdrive—and that was before the blight came, before the farmer’s market had shut down in April.

For the past several months, the blight had been eating its way through the other three founding farms. So now that it was our turn, I knew what it would do. It would take more than this year’s harvest. More than our savings. It would take the soil itself—our entire future.

Mom had never loved Rainbow Fields like Dad and I did. Since the blight appeared and shut everything down, she’d been asking what we were clinging on for. If she knew it had reached our wheat…

The blight would fracture my family and tear us apart.

Some heir I was. I kept seeing that look on Dad’s face—the horror in his eyes—when he realized how badly my efforts to help us had backfired, that I was the one who’d unleashed this blight on all of Hollow’s End.

A fresh wave of shame bloomed in my chest. I shoved against the shed’s splintered doors. It felt good to push back. I grabbed spare gloves, the rattiest pair hanging by the door, caked stiff with crumbling mud—the ones I wore when I was a kid. They barely fit anymore.

Armed with a shovel, I raced back to the infected soil at the edge of our farm.

With every gasp, every thrust into the earth, numbing air bit into my lungs. And I realized I hadn’t put my shoes back on. Dammit. Now my socks were touching contaminated soil, and I’d have to leave them behind, too.

The sharp edge of the shovel dug against the arch of my foot as I pressed down with all my weight. I pulled up the dirt and scoured it, praying for smooth, unbroken brown.

But there were only more silver globs—beads of them crawling everywhere.

I could dig for days, and I’d never get it all out. My hands ached, and I dropped the shovel with a dull thud.

It took everything in me not to collapse beside it.

The blight had burrowed too deep. There was only one way I could think of to slow it down. I had to dig up the fence from our backyard and sink it in here, hard into the soil. I had to block off the corrupted back row of our farm, and the forest looming beyond it.

Yes. That was a plan. Something Dad himself might’ve thought of. I could do that. I could—

My sinuses burned. I sneezed into my glove, and the mucus came out like the soil, flecked with silver.

I stared at it, smeared across my fingers. The whole world lurched.

No way.

I swatted it off against my pants so hard I was sure I’d left a bruise on my thigh, and scanned the fields—could anyone have seen what just came out of me?

But there was only me and the swaying wheat. The empty sky.

I couldn’t be infected. I hadn’t touched it.

I had to keep telling myself that. I knew way too well that if any of the blight rooted inside me, there was no coming back. It was worse than a death sentence. It was…

I needed to shower.

Now. And then move the fence.

I stripped away my socks and gloves. In cold bare feet, I pounded back to the house, jumping over rocks where they studded the path.

The nearest farm wasn’t for two miles, so I did the teeth-chattering thing and stripped on the porch. I paused at the clasp of my bra, the elastic of my underwear. No one was watching, but these days the forest had eyes. And it was hard to forget that laugh I thought I’d heard from the trees. My bra and underwear were fine, so I left them on. As for my beloved purple plaid shirt and my soft, work-worn jeans… After my shower, I’d have to wrap them in plastic and dump them in the trash.

Last time Mom took me shopping, I saw how her eyebrows pinched together when she reached for her credit card. There wouldn’t be replacements—that’s for sure.

Pimpled with goose bumps, I charged inside, straight to my bathroom, and cranked the hot water. With any luck, it’d slough off the top layer of my skin. I scrubbed at my arms and legs. I scalded my tongue rinsing out my mouth. When I spat down the drain, the water came out gray. A little dirty.

Or was I imagining it?

Everything was far away, like I was twenty feet back from my own eyes. A gunky heaviness clung under the skin of my cheeks and forehead.

I don’t know how long I stood there, surrounded by cream-white tile, steaming water beating my body. By the time I blinked myself back into reality, under my head-to-toe dusting of freckles, my pale skin had turned lobster-pink.

I threw on overalls and combed my fingers through my shoulder-length hair, before the chestnut-brown waves tangled into a hopeless mess.

As if it mattered how I looked. My brain bounced all over the place, trying to forget that it was much too late for normal.

I went down to the kitchen and called my parents from the old wall-mounted phone.

The calls dropped to voicemail immediately. I took a deep breath. That wasn’t surprising. Reception was so bad out here that cell phones were practically useless, and Wi-Fi was pathetic—Hollow’s End was stuck in the dark ages, with landlines and answering machines. Back when we still had tourists, the town’s community center played it off as charming: “Just like the good ol’ days! A simpler time!” In reality, though, it wasn’t as simple.

Pacing the kitchen, I tried the Harrises next. As the phone rang in my ear, I stopped in front of our fridge. Pinned under a magnet shaped like a loaf of bread was the hazard-yellow flyer stamped with the official US seal on the front: protect your family from “quicksilver blight.” It was one of the early flyers they’d passed out at the end of February, when the government responders arrived in town. When they still came door to door, and we really thought they might help. Now, they stayed holed up in their tents blocking the bridge out of Hollow’s End. Every couple weeks they flew a helicopter over, dropping the latest flyers—littering our farms and fields, so we had to trudge through with trash pickers, shoving them into bulging recycling bags.

The flyers never said anything new. At the bottom, in big bold letters, this one shouted:

**If you suspect you or someone else may have been exposed to “quicksilver blight,” immediately contact your emergency triage clinic.**

They said the triage clinic could treat us for mercury exposure. Although we all knew the blight was more than mercury. That was, however, the official story being fed to the outside world—Hollow’s End was suffering from an extra-nasty mercury spill—and somehow, any photos or videos we posted online disappeared minutes after they went up, like they’d never been there at all.

As for the dozen folks who had gotten infected and turned themselves in to the clinic this spring, their families hadn’t been able to get any word about them since. Not one had returned.

The truth was: there wasn’t any treatment, let alone a cure.

The phone stopped ringing. “Hey there, you’ve got the Harrises…”

“Mrs. Harris,” I blurted, “it’s Wren! Are my parents—”

“Or you don’t yet, because we’re busy. If you’re calling for a quote on our stud fees, or to join our puppy wait list, don’t forget to leave a callback number!”

Shit. That awful message always got me.

I dropped my forehead against the fridge door. At the beep, I mumbled a plea for my parents to call me back and slammed the phone into its cradle.

My empty hands wouldn’t stop shaking.

I couldn’t move that fence alone, not if I wanted to make any real progress before sundown.

Who else could I call, though? My “friends” from school had barely spoken to me since I was quarantined. They all lived across the bridge in Meadowbrook anyway, inaccessible now, thanks to the government responders’ barricade. All except for Derek. And things with Derek were over—extremely over. Now he was nothing but deleted texts and unanswered calls.

But… he was the only option, wasn’t he?

I allowed myself a good long sigh at the phone, then picked up the receiver and stabbed out his phone number.

It was too late for normal. Too late for feelings, too.

Excerpt copyright © 2022 by Ann Fraistat

Jacket art copyright © 2022 by Marcela Bolivar

Published by Delacorte Press, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York