World War II and subsequent budget cuts brought Walt Disney’s original plans to release the 1940 Fantasia every year as an evolving project to an abrupt end. Even after Cinderella brought the studio back to profitability, Disney still did not have money—and theatres did not have the sound equipment—to plunge back into Fantasia again, partly because those profits were instead invested in the Disneyland theme park and partly because the studio had shifted to a simpler, cheaper animation style. Only one more film in the Walt Disney years—Sleeping Beauty—came anywhere near to Fantasia’s detailed, lavish animation style, and when it flopped at the box office, Walt Disney gave up all hopes of continuing Fantasia.

But as Disney animation joyfully returned to quality and—above all—profitability in the early years of the Disney Renaissance of the 1990s, Roy Disney, nephew of Walt Disney, and arguably the single person at Disney most interested in preserving his uncle’s legacy, had an idea: why not finally fulfill Walt Disney’s vision and create new segments for Fantasia? Perhaps even an entirely new Fantasia?

Disney CEO Michael Eisner was not entirely sold on the idea, but when a 1991 home video release of Fantasia shocked everyone by turning a large profit, he grudgingly gave Roy Disney permission to go ahead with his plans for a sequel. Roy Disney and Thomas Schumacher, president of Walt Disney Feature Animation, began searching for conductors, brainstorming ideas for the project, and dragging Joe Grant, who had worked on the original Fantasia, into the film as a concept and story artist and general “well, this is what Walt might have done” guy. Grant was the only artist to contribute to both films.

But since Jeffrey Katzenberg, then chairman of Walt Disney Studios, was less than enthralled with the idea of reviving Fantasia, work on the film was conducted in odd moments, in between other work, and often almost if not entirely in secret. One work, the Rhapsody in Blue segment, was even originally intended as an independent cartoon short, not as part of that Fantasia folly. This bits and pieces approach meant to things: one, the film did not move into full production until 1997, and two, it turned into a way for the artists to experiment with new CGI techniques along the way—accidentally turning Fantasia 2000 into almost a case study of shifting artistic techniques at the studio.

Arguably the best example of this can be seen by comparing the Pines of Rome segment (aka “the one with the flying whales”) to the Piano Concerto No 2 (aka “the Steadfast Tin Soldier story from the Hans Christian Anderson fairy tale except that in this version nobody dies YAY”). The Pines of Rome was initially intended as a hand drawn animated bit—until, that is, animators started feeding the drawings into the CAPS inking system. As pencil drawings, the images looked fine. But once inked by computers, these first images looked, well, wrong, requiring animators to go back and redraw all of their initial images of flying whales.

“Redraw” meant one thing to Disney: “expense.” The unexpected CAPS issues created a major issue for the director and the animators: attempting to hand animate the rest of the segment, with water effects, would have taken far too long and cost far too much money—and work on the rest of Fantasia 2000 hadn’t even started. They decided to animate the rest of the sequence with CGI instead.

At this point—the early 1990s—CGI was still in its technical infancy, and the result was not exactly optimal; animators ended up needing to hand draw facial expressions and eyes on top of the CGI whales, which creates an odd look in a few frames here and there, a look that only gets odder the larger the screen—a particular problem since this film was initially released only in IMAX format. It didn’t help that this was a rather strange little segment anyway. But in the process of hand drawing eyes on top of CGI images inked from hand drawn images, Disney animators managed to create a program that allowed them to work with multiple animals at once—a program that ended up getting used for The Lion King. The final moments of the CGI whales leaping through water and light gave a sense of just what artists might create with the technology later. I don’t know what, exactly, whales are doing leaping over clouds, or how they got there—maybe they’re on an alien world, maybe they’re dreaming, maybe this is what whales really do when satellites and ships aren’t around, but what I do know is that the final leaping whale sequence was the first step in allowing Disney to eventually create the mass crowd scenes of Big Hero 6 and the spinning snowflakes and soaring ice of Frozen’s “Let It Go.”

Two segments later in the film, and about five years later in real time, Disney finally moved the Piano Concerto No 2 into production. By this time, it was clear that then-partner Pixar had the potential to become a major rival to the studio, and Disney animators wanted their own computer animation department to keep up. And thus, this bit—the first Disney cartoon featuring fully CGI characters, created to look like hand drawn characters, to help set them apart visually. By this point, technology had improved so that the animators didn’t need to draw on top of computer drawings. Instead, they placed the CGI characters against hand drawn backgrounds. It was far more expensive than Disney executives were happy with, necessitating some last minute cost saving by recycling some animation from Bambi after all of this, but it represented another major step forward for the studio. I’m not as enthralled by this segment as others are, and it’s less triumphantly out there and just plain gloriously weird as the whales piece, but the animation is much smoother, showcasing what Disney would be able to create in just a few more years with Tangled.

Disney animators also experimented with a new look for the Rhapsody in Blue sequence, a cartoon supervised by Eric Goldberg when work on Kingdom of the Sun came to a crashing, terrible halt in 1998. We’ll be discussing that crash over the course of the next three posts, but for now, what the crash meant was that Eric Goldberg and his team were left twiddling their thumbs, an idle moment that Disney executives thought should be filled with, you know, actual work. Say the cartoon based on Al Hirschfeld’s caricatures that Goldberg had been toying with for several years.

Al Hirschfield’s idiosyncratic caricatures had filled New York newspapers and magazines for decades before inspiring some of the looks of the Genie in Aladdin, a character supervised by Goldberg. The animator/director now wanted to expand that into a study of New York life in the 1930s, based on Hirschfeld’s drawings, set to Rhapsody in Blue. The entire cartoon had a startlingly different look from pretty much anything else Disney had created then or since—largely because this is less “Disney,” and more Hirschfeld’s cartoons finally looped into a story and animated onscreen. Rendering that look through the CAPS system proved to be so tricky that, as it turned out, the cartoon meant to fill in a production delay ended up causing another production delay—on Tarzan.

I think the delay was worth it. This is one of the most memorable, tangled, yet compact segments, using its cartoon format to convey critical information—like the scarcity of jobs—in an instant. It tells the stories of four lost New Yorkers and the people they encounter, soaring during a moment when they all dream of a happy moment lost on the ice or in music, before triumphantly earning their own happy endings. Am I just a little concerned with a cartoon sequence where part of the happy ending involves leaving a wealthy woman dangling in the air after a day of very hard shopping? Well, kinda, yes, but on the other hand, as the cartoon indicates, she’s indulging in luxury items during a financially terrible time (the Depression), and she dragged her miserable husband away from a monkey. I mean, really.

The segment is also filled with tiny visual jokes—watch carefully for the appearance of “Nina,” a name Hirschfield snuck into most of his illustrations, or the appearance of composer George Gershwin. One of my favorite moments occurs early on, when a cat triumphantly opens up a bottle of milk—only to get knocked into the milk bottle a few seconds later by the frantic construction worker, late for his job: I feel I’ve duplicated the expression on that poor, slinky cat’s face on many mornings. The little girl during her ballet class struggles could also be me.

Eric Goldberg was also directly responsible for one of Fantasia 2000’s other highlights—The Carnival of the Animals, or, more simply, “the one with the flamingo and the yo-yo.” Goldberg not only directed the segment, but drew every frame for what would eventually be 6000 watercolor paintings on heavy bond paper, to create Disney’s first and last cartoon done entirely in watercolor, with the CAPS system later used to blend characters and background together in the first time the CAPS system had ever worked with watercolor—an advance that would prove useful later for Lilo & Stitch. Art director Susan Goldberg, Eric Goldberg’s wife, chose the brilliant colors for the segment.

Disney had used watercolor for backgrounds in earlier films, most notably Dumbo, and would use watercolor backgrounds again for Lilo & Stitch, but Disney had never before attempted to use watercolor for effects shots (splashing water), characters (flamingos and the yo-yo) and backgrounds. The cartoon demonstrated why: doing an entire cartoon in watercolor turned out to be labor intensive, hideously expensive, and still needing computer assistance to be transferred to film.

The general idea of putting a yo-yo together with Carnival of the Animals came from Joe Grant, although no one seems to be quite sure who had the idea to include flamingos. It works, though, because let’s face it: a disgruntled flamingo sulking because he can’t play with his yo-yo anymore is comedy gold. It’s a segment that can be read, if you’re feeling serious, as a story of creativity and individualism triumphing over conformity, or it can just be read as a silly cartoon about a flamingo and a yo-yo. Your choice.

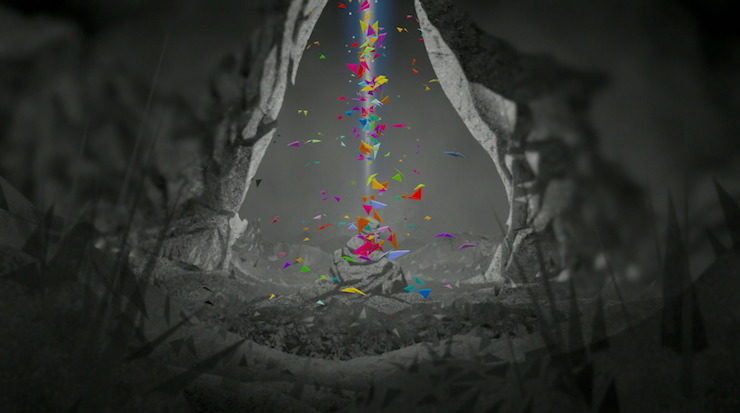

The other outstanding section, and arguably the most glorious, or, at the very least the section most associated with fine art prints, is the final sequence, The Firebird Suite. Inspired by the eruption of Mount St. Helens, the animation here tells a triumphant story of destruction and rebirth, anchored by a sprite who shifts from water to ash to rain to glowing green life. This work was supervised by directors from Disney’s Paris studio, who had been contributing small bits to earlier Disney films: it features a mix of CGI and hand animation. I don’t have much else to say about it except to suggest watching individual frames, which contain some of the most beautiful images of the film.

Visually, some of the effects of The Firebird Suite sequence—the falling leaves and butterflies—almost serve as callbacks to the short Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony sequence that starts off the film, creating a strong framing for the film. This was mostly a coincidence: the segments were supervised and animated by different artists, although both segments used the same Houdini software, which might have helped to create a similar look. Otherwise, the segments have little in common: like the Toccata and Fugue piece that starts off the original Fantasia, this is an abstract piece, featuring “dark shapes” fighting against “light shapes,” many of which look like bats because, while creating the piece, the artists visited the zoo and looked at bats. One of the latest segments finished for the film, it showed a seamless blending of hand animation and CGI images.

That left only two more sequences to match the original’s eight. For one, Disney used The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, the hands down popular favorite from the original Fantasia, and still an intense, enthralling bit of animation in its own right. For the other, Disney decided to match the Mickey Mouse cartoon with a Donald Duck cartoon retelling the story of Noah and the Ark, setting it to a rearranged version of Edward Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance, aka “that thing they always play at graduations.”

This segment garnered considerable criticism from viewers not happy with Disney’s decision to give a Donald Duck cartoon a Biblical theme, and even less happy with what was perceived as an irreverent approach to Noah’s story. In fairness to Disney, this was hardly their first use of Christian themes in their animated films; Jeffrey Katzenberg had even suggested that Disney do an animated version of Cecil de Mille’s The Ten Commandments, a project that eventually became Dreamworks’ The Prince of Egypt, released the year before Fantasia 2000. In less fairness to Disney, both The Prince of Egypt and Disney’s previous use of Christian themes had been largely respectful, serious takes on religion, not cartoons featuring Donald Duck getting squashed by an elephant.

I have a different complaint. As dramatic as it is to see Donald and Daisy constantly just missing each other, the Ark just isn’t all that big, and it’s a bit hard to believe that Donald and Daisy wouldn’t run into each other at some point over forty straight days and nights of rain plus however long it took the floods to recede. Or that Noah or the other animals wouldn’t notice two sad little ducks, ask questions, and start a search party. Not buying it. On a production note, the segment has a few moments where Donald Duck is moving but the animals behind him aren’t, which given the use of the CAPS system, is inexplicable. The moment apparently designed to conjure up memories of the opening sequence of The Lion King mostly reminds me that The Lion King did a better job of summoning animals to a single location.

But Donald does get to have a few of his usual Donald moments—rhinos stepping on his feet shortly before he gets squashed by an elephant, that sort of thing. And I’m amused by the various visual jokes—two rabbits hopping into the Ark, followed, a few minutes later, by several rabbits hopping out of the Ark; Donald frantically using a snake as a rope—accidentally saving two mice in the process; and a Hidden Mickey with a Hidden Minnie.

To connect the segments, Disney decided to make another nod to the original film by including live action introductions to each film. But rather than hire another music critic to introduce each segment with a dull narration, Disney instead hired a varied group of actors, musicians and stage musicians to narrate the film. Frankly, it’s not a huge improvement. Using different actors did at least keep the bits between cartoons from getting too monotonous, but the jokes often fall flat, and Angela Lansbury seems unsure if she’s introducing a cartoon or presenting a Tony Award. About all I can say is that at least these bits are short.

Much more visually interesting was the technique used to introduce and end the film—basically, sending frames of the previous Fantasia and the current Fantasia bending and twisting through the screen: it’s a lovely connection to the previous film and arresting on its own.

But for all the beauty of two of the individual segments, the originality of the Rhapsody in Blue segment, and the sheer fun of those flamingos, this remains an oddly lightweight film. Part of the problem is its length. Like the original, Fantasia 2000 consists of eight musical segments, plus the narration, but where Fantasia runs for about two hours, depending upon the cut, Fantasia 2000 runs for only 75 minutes—15 minutes of bad jokes and watching the end credits, and sixty minutes of actual animation. Granted, the original also includes a brief jazz sequence and that moment with the soundtrack, adding about ten minutes to the film, but even with that, pretty much every sequence of the original is longer than its corresponding sequence in the continuation. This is particularly evident with the opening abstract sequences—under three minutes for the brief excerpt from Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony in the continuation, versus nine minutes and 25 seconds for Bach’s Toccata and Fugue.

Shorter is not necessarily a bad thing: a strong case can be made that the original was too long, putting at least some viewers (me) to sleep in some sections. Fantasia 2000 really doesn’t have any dull sections, and in the Firebird and Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony sequences, it sometimes matches the sheer beauty of the original. But perhaps because of that surface exuberance, it lacks the emotional depth and—for the most part—the wonder and the richness of that earlier work. Nothing here is as delicately beautiful as The Nutcracker Suite sequence, as demonic as Chernobog, or as original as the graceful ballet dance of a hippo fleeing a crocodile.

On the other hand, Fantasia 2000 does have a triumphant flamingo with a yo-yo.

Fantasia 2000 had something else for Disney: it was their first feature to be released on IMAX. Unfortunately, this meant that for several months, only viewers with access to IMAX screens were able to see the film. Far fewer IMAX screens existed in 1999 than in 2016. Getting to see the film meant an actual road trip even for me, living in highly urbanized South Florida. My friends and I ended up travelling a full hour down to Coconut Grove, the only place showing the film.

We were among the very few people in the audience.

For me, it was worth the trip. On IMAX, most of this looked great: the one exception was, surprisingly enough, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice: blown up to IMAX size, each and every tiny nick and grain that has crept into that segment since 1940—even after some digital cleanup—was clearly visible, making the segment look grainier than the slick sequences that bracketed it. I strongly advise watching that segment in the restored original version, in the correct aspect ratio, on a smaller screen: it continues to hold up well, especially without the distraction of those tiny nicks and grains.

But for Disney, the IMAX only release created an entirely different problem: it kept revenues from the film down for months—while allowing word to get out that although Fantasia 2000 had some neat stuff (mostly the Rhapsody in Blue, flamingo, and The Firebird Suite segments) and was probably a lot less likely to bore the kiddies, it wasn’t the original. By the time the film arrived in regular theatres, the audience had vanished.

Thus, like the original, Fantasia 2000 turned into a box office flop. As an exercise allowing Disney artists to play with new software and develop new ways of combining hand animation and CGI, it did contribute to other films in production. But given the studio’s eventual switch to full computer animation, from a financial perspective, that was only a temporary contribution. Disney was able to sell numerous art prints and other fine art based on/inspired by the film, but the film has yet to recoup its production and marketing costs.

Then again, it took Fantasia years to turn a profit. And in the meantime, Fantasia 2000 and the film that immediately followed it were able to fill in an unexpected, and very unwanted, release gap for the film that should have been the glorious end of the Disney Renaissance, and instead, was, well, something else.

But before we get to that film, the other filler film, such a filler film that it wasn’t even listed among Disney animated films for years: Dinosaur.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.