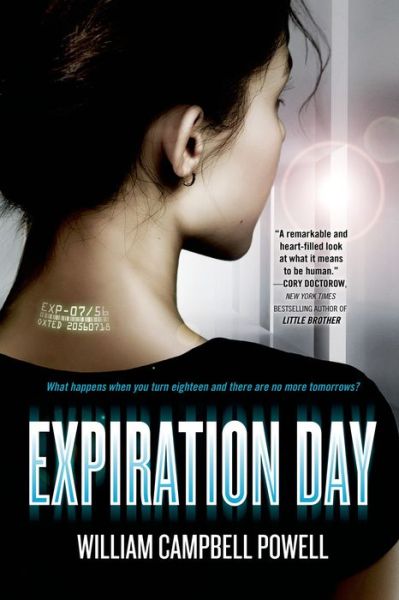

Check out Expiration Day by William Campbell Powell, available April 22nd from Tor Teen!

Tania Deeley has always been told that she’s a rarity: a human child in a world where most children are sophisticated androids manufactured by Oxted Corporation. When a decline in global fertility ensued, it was the creation of these near-perfect human copies called teknoids that helped to prevent the utter collapse of society.

Though she has always been aware of the existence of teknoids, it is not until her first day at The Lady Maud High School for Girls that Tania realizes that her best friend, Siân, may be one. Returning home from the summer holiday, she is shocked by how much Siân has changed. Is it possible that these changes were engineered by Oxted? And if Siân could be a teknoid, how many others in Tania’s life are not real?

Driven by the need to understand what sets teknoids apart from their human counterparts, Tania begins to seek answers. But time is running out. For everyone knows that on their eighteenth “birthdays,” teknoids must be returned to Oxted—never to be heard from again.

Sunday, July 18, 2049

What a funny old day!

We got a robot today. And it was my eleventh birthday. So I thought I’d start to write a diary, because it was a weird day, and if you can’t even write a decent diary when you’ve got something to write about, what chance have you got when the days are dry and dreary?

But I’m not going to start every entry with “Dear Diary” or anything so Victorian. That would be just so wet. Anyway, I want to decide who’s going to read it. Whoever you are, my distant, unknown friend, I need to see you in my mind.

Maybe no one will read my diary, except me when I’m ninety. So just in case, “Hello, me-of-twenty-one-twenty-eight! This is me-of-twenty-forty-nine.”

Maybe, though, my grandchildren are reading this. “Hello, grandkids! This is your dotty granny Tania writing, before she lost her marbles. I hope you’ve found me a nice home.”

No, I don’t hope any such thing. If I have to become anybody’s granny, please don’t let me be a boring granny. Instead I shall be a grand Dame, knighted for my services to the country, and I shall tell fabulous stories, mostly true, about my adventures as a spy, or a detective, or an actress. So by 2128 you’ll need me, whoever you are, because there won’t be many like me left.

And if you’re just a boring old historian, or some kind of slimytentacled alien archaeologist called Zog from the Andromeda galaxy, trying to find out who on earth I am and what human beings were…

Do you have churches in Andromeda, Mister Zog? Weddings, christenings, and funerals? Too much detail, I think, at least for today. Anyway, my dad is a vicar. And in these times he has a lot to do. He says thirty years ago the churches were empty. Now they’re full. Full of unhappy people, looking for help to make things bearable. Looking for the little rituals that make things feel normal.

The church business is good. But vicars are still poor. Mum says he’s keeping half the village sane, but still we live on people’s cast-offs. We have Value Beans in the larder. Our vid is someone’s old 2-D model. And our “new” robot is a reconditioned ’44 model, donated by a kindly parishioner.

But we have a robot, a real, honest-to-goodness robot. And Dad says even the bishop only has a ’47 model. Ted, one of the churchwardens, dropped him off. Him? It? I’m going to keep on saying “him” for now, as his voice was rather deep, and very “Home Counties.”

We called him—the robot—Soames. It seemed like the perfect name for a 1930s butler—right out of an Agatha Christie 3-Dram. Dad activated him, and I watched as the eyes lit up for the first time. I asked Dad about that, and he smiled.

“Yes, there really isn’t any need for glowing eyes. They’re more for show, part of a retro look, that the psychologists say makes us feel more comfortable with them around. We see all the old-fashioned twentieth-century sci-fi movies, and we laugh, because they’re so quaint. This is the same thing—robots deliberately made to look clunky and antique, and act like it, too, so we feel superior, rather than feel afraid.”

We had to do an imprinting, of course, to get Soames to recognize the voices of his new owners, so that he’d obey our orders. “Michael Deeley, primary registrant. Acknowledge.” That was Dad.

“Acknowledged.”

“Annette Deeley, secondary registrant. Acknowledge.” Mum.

“Acknowledged.”

“Tania Deeley, junior registrant. Acknowledge.” Me, reading from the instruction manual and sounding very formal.

“Acknowledged.”

And that was it. Soames would obey Dad, then Mum, then me. In that order. There were a bunch of other commands built into his brain that we couldn’t override, sometimes called the Asimov Laws, after some ancient writer who came up with the idea. Dad says Asimov’s original laws were very simple, but Soames’s version had been made very complicated by the lawyers. So under stress any robot just became completely useless.

Anyway, we put Soames to work doing the washing up. He didn’t break anything, but I could have loaded up the dishwasher myself in half the time. Tomorrow, though, he will be faster, because he’s learned what to do and where to put the plates afterward.

And then, because it was the summer holidays, there was no school, so I got him to play table tennis, because it was my birthday and Dad said I deserved a treat for that. Soames spent most of the time picking up the balls, when he didn’t crush them underfoot (two destroyed) or knock them into the lamp shade (one out of reach).

Then we took him around the house, showing him where everything was. So we can tell him to tidy the house now, and everything will find its way back to where it was on my eleventh birthday. Or whenever.

Big deal.

Okay. I’m not frightened of domestic robots, honest. But can you make one that can play table tennis, please?

Monday, July 19, 2049

Hmm. If you are Zog, that probably didn’t make a lot of sense, did it? I mean, you must think that Soames is the height of our technology and I haven’t said who I am and where I live and all sorts of stuff.…

I’m Tania Deeley, though I did mention that in an offhand sort of way. Eleven years old—of course—and an only child. I live in a Green Zone village, just outside London, where my dad’s the vicar and my mum’s, well… Mum. I go to school in the village. I don’t really have any proper friends at school, but there are a few I play with sometimes.… It’s okay, I suppose.

Dad’s busy right now—vicar stuff—and he’s banished me upstairs, to the spare room with all his books. It’s not really being banished if I’m here—it’s my favorite place, full of treasure. Books. Proper books: books that have never been digitized. I’ve loved this place since I was tiny, and nobody ever told me the books were too old for me, so I just read whatever came to hand, curled up in the big reading chair, soaking up every word. For once, I’m not reading a book, but I am in the reading chair, snuggled up and rereading yesterday’s diary entry in my AllInFone.

My new AllInFone, Mister Zog. Not reconditioned, for once. Not some parishioner’s cast-off. It was yesterday’s other present, my actual birthday present, as really Soames wasn’t my present. It’s got this sweet diary app that can either take voice dictation, or I can type on a full-size holographic projection keyball, and it’s all encrypted, so no one can snoop what I write. I won’t go on about it, in case you think I’m a gadget freak, which I promise you, I’m not. But it is neat. End of gloat. Done.

Mum’s upstairs, too, pottering around, doing jobs, though Dad might call her down later. She helps him a lot with the counseling. When the “parents” come round, trailing the pieces of their broken world for him to put back together.

When their Ellie or their Sammy or their Vidhesh goes back to Banbury, everything comes apart.

Today it’s Mr. and Mrs. Ellis, so that means it’s their Julia heading back to Oxted. Oxted, Mister Zog? The Robot People. In Banbury. And before you ask, no, Julia’s not their “Soames.” She’s their daughter. The polite word that the grown-ups use is a “teknoid.” But I’ve spoken to her. She’s just a Mekker. (Dad says that’s not a nice word. So don’t you use it, Mister Zog.)

Listen, Mister Zog, I don’t eavesdrop when Dad’s doing vicar stuff, but sometimes voices do carry. And then I can’t help putting two and two together. So I’ve got a good idea what’s going on right now. Mr. Ellis is taking the lead, while Mrs. Ellis is sitting, sobbing, as they explain to Dad how Julia’s too much to cope with. How it was all right when she was little, it was just like having a real daughter. But she’s grown up too much.…

I’d asked Dad about it while we were waiting for the Ellises to arrive.

“Dad, why are they sending her back?”

“Because the illusion is broken. Because they can no longer believe Julia is their human child.”

“But what’s changed? I mean, she looks the same and acts the same.”

“And talks the same? Yes. They wanted a daughter so very much. But they couldn’t have a child of their own. So they went to Oxted and got themselves a teknoid.”

“Teknoid?”

(Yes, Mister Zog. I only learned the word today, when Dad told me. So now I’m telling you. So just sit still at the back of the class and don’t interrupt.)

“Sorry, Tan. Teknoid is from the Greek ‘teknon,’ meaning ‘a child.’ That’s just your dad showing off his Greek from Theological College. A teknoid is an android that specifically looks like a child. So, yes, picking up from our chat yesterday, Oxted could make Soames look and speak and move exactly like a human. But it’s incredibly difficult and expensive, so they don’t.

“They have to do it for the teknoids, because we have to believe they’re human. The thing is, Tan, if you don’t do it quite right, it’s really creepy. It’s part of what vicars have to learn, to help them counsel people. The phenomenon is called the Uncanny Valley, after the title of the paper that first suggested the theory, back in the nineteen-seventies.”

“So?”

“So something has happened to break the illusion, and Julia is now in the Uncanny Valley. The illusion is so fragile, maintained only by the initially strong desire for a child. Maybe it’s an accident that’s triggered it. Maybe it’s just an accumulation of little oddities. I’ll find out when they arrive. Either way, the illusion is ended, and the Ellises can’t bear the presence of their unmasked teknoid. Love has turned to fear. And guilt. Which is what I’ve got to help the Ellises get through now.”

At which, with perfect timing, the doorbell rang, and I scooted upstairs.

That made sense. Suddenly it’s all over school that such-andsuch is a robot, and it gets back, and the charade is over. The parents try to tough it out for a few weeks, but they know everyone else knows, and they buckle. Sometimes they move away, try to make a new start. More often they just make the phone call to Oxted. So I guess they’re organizing the “memorial” service with Dad now. “Our daughter, sadly taken away before her time…”

And then you see every kind of silliness that grown-ups can do. Blaming each other, fights—that’s just the start. Divorce, suicide, even murder—though that last was in St. Mark’s parish.

Just because nobody can have kids. Well, almost nobody. And nobody knows why. It’s just something that’s happened. Some said that it was all the radio waves and microwaves messing up our DNA. Others said it was the gigahertz radiation from all the computers doing it. Global warming and pollution got blamed, of course. And there were some really weird theories, too. There was one scientist who claimed that every generation lost a certain amount of information from the gene pool, so we’d just reached the point where we no longer had enough information left in our genes to build a fully working human.

Wow! So I’m a real rarity. An eleven-year-old girl. Just so you know, Mister Zog. If you have a waist, you really ought to bow. Otherwise you could wave your tentacles reverently.

So there’s me (and a few like me). All the other kids in the world are just robots. Realistic robots—not clunkers like Soames— but like Julia Ellis, a near-perfect copy of a human child. Good enough to fool the maternal instinct. Good enough to stop the riots.

Even good enough to play with sometimes.

Sunday, July 25, 2049

Sunday. Family service, and Julia’s Memorial Service. Pretty much as I expected. Photographs of her growing up projected in 3-D. A baby, sleeping peacefully. Flick. A chocolate-mouthed toddler, running in the garden. Flick. First day at school, angelic in her school uniform. Flick. Prize day—Julia collecting third prize for spelling. Flick. Flick. Flick.

Dad stands at the front, delivering the eulogy. A beautiful little girl, with a marvelous future. A life cut short, tragically short, by an unspecified illness. God has called Julia home. May He bring comfort to the parents.

Ted’s yawning. He’s heard it all before. The young mums and dads, with their own kids, look smug or terrified.

There’s no body and no coffin, of course. That would be silly. Oxted has already collected Julia and taken her back to Banbury.

Dad was late back after the memorial, and he was in a foul mood because of it. He hates memorials; he knows they’re necessary, but he hates the lies. “It’s not why I became a minister,” he says, every time.

Dad believes in God. But the Bible doesn’t say anything about robots, and I guess that’s confusing for a minister.

And when he’s said that, he sighs and adds, “I wonder how they’ll cope.”

As far as I can tell, they never do. I said robots were “good enough to stop the riots.” Well, they were and they weren’t. We still have our riots, though robots have taken them off the streets. Dad says it’s just that now we have them one couple at a time, in the privacy of our own homes.

Saturday, August 21, 2049

We’re on our holidays.

We’re going to a theme park, of course, because that’s what everybody does. It’s escapism, and the parks make no bones about it. “Let us take you back,” they say, and they give you a week living in the past. Pick your era, there’s a park to match. Any time—except the last thirty years, because that’s a little too painful for most people. So, where do you think we’re going, Mister Zog? With the whole of human history to choose from, we could go back to, oh, the time of the British Empire, or the Roman Empire. Oh, yes, there are such parks. Unfortunately we can’t afford them, not on a vicar’s salary. So we’re going back to… the 1970s!

It’s so embarrassing.

I have to admit I was curious about the 1970s. When Dad said that was where we were going, I nearly threw a wobbly myself. Oh, Mister Zog, where do I start about the 1970s? I knew a bit from history—the Energy Crisis, the Winter of Discontent, the IRA, the birth of Thatcherism. And Mum’s got some redigitized old photos—really faded because back then they couldn’t make color dyes to last—which she says are of her granny and granddad at Blackbushe in ’78 for a Dylan gig. She sounds so awed whenever she says the word “Dylan,” like he was some amazing being from another planet, come to visit us. We’ve been listening to some of his music in the car to get us into the feel of the decade. It’s all right, I guess, but I hope we don’t have to suffer a Dylan tribute band. It’s not the music, you understand, Mister Zog. I just think Mum and Dad will be too embarrassing.

But as for Great-Gran and Great-Grampy, I don’t honestly know which is which. The hairstyles and clothing in the photo give nothing away—all perms and frilly shirts, and shades that make them look like weird half insects. Am I going to have to dress like that? It might be fun, but I think it’s going to be just creepy.

We’re in our hotel room now, and we’ve come in through the modern entrance. Once we’ve changed, we have to put our modern clothes into sealed storage, and stay in theme for the rest of the week. There’s no vid (again. Why do we always go on holiday where there’s no vid?) and no TeraNet access. They had computers in the 1970s, but they were huge things, with whirring tapes (yes, really) and disk drives the size of a car wheel. You could afford a computer if you were a big university or a hospital—they were called mainframes—and there were minicomputers and…

Sorry, Mister Zog. Too much detail.

Anyway. My point is that once again we’re stuck in a technodesert, and my folks have chosen to come here. When I finish writing this, I’m going to have to put my AllInFone into storage with the clothes and any other contemporary gadgets, and go down to the other lobby in the hotel—the 1970s lobby. I’m going to try and keep notes, but the rules say only pen and paper.

They caught Dad trying to sneak his AllInFone out of the room. There’s a detector at the other door, which picks up the keepalives that all AllInFones have to transmit by law, and a very polite porter informed him, “You can’t take that with you, sir.”

“Oh, I didn’t realize…”

Which was a complete lie. Daddy, you’ll have to confess that to the bishop—I was watching in the mirror, and I saw you look round most furtively as you sneaked it into your pocket.

We went down to the lobby.

It was fascinating. I’ve done a project on the ’60s and ’70s, with all the fast-changing styles, and this place captured them all. Everyone was glammed up for the disco, our opening event. Everyone was covered in glitter and makeup—Dad had done a mini-strop in the room, when he realized that everyone meant everyone—and the clothing was equally over the top.

Platform shoes.

Huge shades.

Flares.

Hot pants.

Yep. I was wearing hot pants. Lilac hot pants. They’re like shorts, but mine had a bib front and it went over a plain white blouse that was all frills and cuffs. Short little white gym socks— cute (not)—and the unevolved distant ancestors of a pair of trainers. I’d nearly had my own strop, but Dad beat me to it, and you don’t show up your dad by out-stropping him.…

It was truly awful. Not least, because I still have preteen legs—like sticks, they are. There’s a word for legs like mine. Gangly. I count my knees, sometimes, and I know I have just two, one on each leg. But dressed like that, I felt like it was more—a lot more, with different numbers on each leg. And hot pants are designed to go over a proper bottom and hips, and I don’t have either yet.

Mum and Dad, of course, were now throwing themselves into character; they were loving it. Dad was wearing near-luminous green flares and a sleeveless knitted jumper over a magenta shirt with a huge collar. I love my dad to bits, of course, but nothing could have been better designed to show off his pot belly. Mum… well, Mum had ended up in a pale lime party frock with orange polka dots. And she’d chosen to wear platform shoes, so she was… wobbling. Now, Mum has a nice trim figure—she exercises regularly, plays squash and tennis with some of the other young mums of the parish. So she shouldn’t have been able to wobble. Yet, wearing those shoes, she quivered.… It was just gross, and I really wanted to hide. If you ever manage to break the encryption on my AllInFone, Mum, and you’re reading this, I’m sorry, but that’s the honest truth, written for Mister Zog.

But there wasn’t anywhere to hide. I looked around me and the scene was repeated twenty-, no, forty-fold, with minor variations. The worst excesses of 1970s dress, rolled up into a lobby full of garishly attired holidaymakers, making their way toward the temple of tastelessness that is a grown-ups’ disco.

It wasn’t just adults, of course. This was a family holiday, and I wasn’t too surprised to see myself in duplicate. Not literally, of course, but dotted around were a dozen or so embarrassed kids from maybe ages seven to thirteen, trying hard not to look at their parents, trying not to be seen by anyone at all.

We drifted over to the dance floor and found a family table. There was another family at the next table, with a young lad, who looked about my age, plus or minus. He smiled at us, a big, freckly smile beaming out from under a ginger mop. I nodded back, and his mum caught the motion, and she smiled, too. It wasn’t long before we’d pulled the tables together, and the adults were chattering away. And then my dad and his dad were wandering off to the bar to get drinks.

“What’s your name?”

I didn’t catch on at first. Ginger Mop was talking, but I didn’t register the words. I’d been looking at Mum kind of sideways. Actually, now she’d sat down she’d stabilized, and was back to Trim Mum again.

“What’s your name?”

“We’re the Deeleys.”

He looked annoyed.

“I know that. What’s your name?”

“I’m Tania.”

I really didn’t want to say any more than that. The disco was playing early Bowie—“The Jean Genie,” I think—and I was worried Ginger Mop was going to ask me to dance. Then he’d count my knees, and it would be some large odd number, and he’d laugh, and I’d have to kill him, and they’d throw me in jail—end of holiday.

“John.”

“What?” I really wasn’t with it.

“John. My name’s John. You can use it, you know, if you want to attract my attention.”

“I’d tagged you as Ginger Mop.”

I didn’t want company, at least, not some robot kid, so frankly, I was trying to be rude. Just a little bit, but it was water off a duck’s back to him. He just grinned and pushed his fingers through his hair.

“Yeah, it is pretty scruffy. I could get a job as a mop, too. So if you’re going to call me Ginger Mop, what do I call you? Raven?”

“I suppose so.”

Well, my hair is pretty black, and I didn’t mind him noticing. He was so determinedly friendly and cheerful, too, and he wasn’t at all put off by my get-lost tactics.

“Well, then, Miss Tania Raven Deeley, how about a smile and a hello for John Ginger Mop Czern?”

I smiled briefly and nodded hello. Without much thinking, I raised my hand and carefully brushed back a stray black hair. He grinned back at me, and futilely pushed his own wild locks back, only for one to drop straight back in front of his bright blue eyes. I couldn’t help myself, and gave him a broad grin in return. For a robot, he was an all right human.

“Okay, John. I give up. I’m friendly.”

“That’s better.”

It turned out Mr. and Mrs. Czern were from London. They owned a little corner shop, selling groceries, magazines, what-haveyou. If you needed something and you couldn’t be bothered to get the car out for a trip to the supermarket, the Czerns would sell it to you. John helped out in the shop, when he wasn’t at school or doing his homework.

“I help out quite a lot. They treat me a bit like a servant. You know: do this, do that…”

“Don’t you have a domestic robot to help?” But I knew what the answer would be.

“No. We don’t make much money in the shop. Enough for a decent holiday. A robot, though, that would be a luxury.”

Two robots, I thought. Two robots would be a luxury. The first robot is a necessity. And I thought of that gift of clunky old Soames. If my parents hadn’t had good genes, there was no way they could have afforded even that necessity.

“I know. Dad’s a vicar, so we don’t have much money, either. We were given our robot, secondhand.”

Our conversation was getting rapidly depressing. Any longer, and we’d be crying into our drinks. Which reminded me, where were the dads with the drinks?

Right on cue, they appeared out of the faceless crowd, Dad leading the way and Mr. Czern carrying the drinks on a tray. Mr. Czern served everyone from the tray. He was a round, jovial man, quite short, and he chuckled and flourished as he doled out the glasses.

“Babycham for the ladies. Watneys Red Barrel for the men. And a cola for the kids. Pretty authentic, huh?”

I wondered how he could be so sure. As Dad drank his Red Barrel he grimaced, and I asked myself, if a beer were that awful, why would anybody have kept the recipe for more than eighty years?

I caught John’s eye, and I think he must have been thinking something similar, because he mimicked Dad’s grimace, and then pantomimed tipping the beer away. He winked, and I winked back, and took a sip of my own drink.

Yeuch! It was foul! Cloying and sweet. Another recipe that should have been left in the vault…

I don’t think I’ll dwell on the awfulness of that disco. Or indeed the rest of that week. The ’70s music was perhaps the best bit, but what did Dickens say? “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness.…” Perhaps it was true of the ’70s, too, except I didn’t see any wisdom on show at the theme park.

All in all, the ’70s was a dreadful decade. One night they gave us all candles to take to our rooms, and then they staged a power cut. One moment we were all watching a grainy Panorama documentary on the TV (yes, a TV) about the energy crisis, and the next moment, the lights went off, and the picture shrank to a glowing point. There was a faint glow from the TV screen— just enough to find the candles. I think they cheated a bit, with hidden lighting in the walls, so nobody tripped over anything and broke a leg. In five minutes, everybody was stepping out of their rooms holding lit candles, and making their way, yes, down to the bar. Strangely, nobody complained that there was power for the beer pumps.…

The high point was a trip to a coal mine. It was a reconstruction, of course, and we used a simulator to take us “underground.” I’d got sort of used to us being with the Czerns, and I liked John’s sense of humor. So when we were all dressed up in orange overalls and hard hats, it seemed pretty natural to let him take my hand and lead me through the ill-lit tunnels.

They didn’t go anywhere, of course—no more than ten or twenty meters in total, with a couple of twists and short side passages to make it vaguely interesting. And everywhere there were the oohs and aahs of the tourists, and the drone of the guide talking about “the last decade in which Britain could truly be said to have a mining industry” or the “naked grasping after power of the unions.” It didn’t make a lot of sense, but it sounded very grand.

And so it came to the last day. There was a gala party in the bar, with a Slade tribute band. It was glittery and loud, and they stomped about on giant platform shoes, singing “Gudbuy T’ Jane” and “Cum On Feel the Noize.”

In between songs John had asked me for my PTI—my public TeraNet ID—and I was in a turmoil. Should I give it to him? I mean, he was nice, but he was only a robot. With a wild ginger mop that wouldn’t obey orders, plus very cute freckles.

What am I saying?

Oh, dear, Zog. I think I’ve got my first crush on a boy. Because I gave him my PTI, and we danced—me in my ridiculous hot pants and all my knees showing—and I gave him a little peck on the cheek when I thought Mum and Dad were looking the other way. And then the band played “Far Far Away” and we danced close and I whispered to him, “Are you real?” And my heart leaped as he replied, “Yes, I am real.”

Interval 1

A remarkable find. Truly remarkable. I cross the galaxy to find the first records of the Dawn Civilization and I find this. Encrypted and forgotten, but surviving through uncounted millennia, for me to find.

So I am your Zog, and I will learn about you, Tania Deeley, coy and precocious as I perceive you to be. I have time to listen to you, Tania Deeley, we don’t have to rush. There’s no wormhole about to close. Sadly, there are no wormholes anywhere to speed us across the universe.

No, Tania, I came the long way, through normal space, though it has taken millennia.

My kind has time.

Monday, September 6, 2049

It was back to school today. The holidays are over, and it’s a new school for me. The Lady Maud High School for Girls, and I have to take a bus from the village—past my old school—to get there.

Such a panic from Mum this morning. Have we been practicing the route to school for weeks, or have we been practicing the route for weeks? As I leave the house, staggering under the weight of PE, hockey, and swimming kit, plus sandwiches, ruler, pens and pencils, two sharpeners and two erasers—“just in case you lose one, dear”—calculator (why? if I have an AllInFone), padlock for locker, with five—count them—five parental consent forms, she was still calling, “Have you got your bus pass?”

And Dad was walking with me “as I have to go past the bus stop anyway,” but he wasn’t carrying anything for me “as you have to get used to it.” He wasn’t panicking—not like Mum—just being overprotective of his “little girl.”

Girls of all ages and sizes waited at the bus stop, the older ones chattering already about where they’d been over the summer holidays. I’d already decided if I met anyone I knew, I’d stayed home all summer. I had not, repeat, not been anywhere near a theme park. If tortured, I’d admit to a visit to feudal England—that’d kill the conversation—but a trip to the 1970s? Uh-oh.

Dad’s back disappeared round a bend in the road—I was pretty sure he’d just go round the block and return home—and I was on my own. I suddenly felt a chill—some of those other girls looked awfully tall and mean. I had to take a deep breath and remind myself that they were most likely robots, and couldn’t hurt a human.

“Hi, Tania!”

The friendly voice came from right next to me, and I jumped in surprise. It was Siân, a girl I knew from the village school. I’d not seen her over the holiday—she’d been away—and I was surprised to see how much she’d grown in the few short weeks. Taller, of course, but all her elbows and angles had suddenly become curves—she looked awesome—and I felt totally awkward and out of place beside her.

And then I twigged. Siân had had a revision over the summer. Robots couldn’t grow like humans, but to preserve the illusion of humanity, they had to appear to get older. So every year or two each robot child would go back to Oxted Corporation for a week or so and emerge with a new look—the word was “revised.” The same personality, but a new body, suitably older. A standard revision was fairly basic, but was included in the contract. It didn’t look like Siân had gone for the standard revision, though.… No, it certainly wasn’t the cheap option, but Siân’s parents didn’t have to worry about such trifles, and had used the holidays to revise Siân into her early teens.

Of course, it was bad form to mention it, so I closed my mouth, nodded hello, and then asked casually, “How was your summer, Siân? Go anywhere interesting?”

“So-so. We went to Egypt. Daddy had to go there on business, so he took Mummy and me, too. We did the sights, took a Nile cruise. Spent a for-tune in the markets. Nothing special, just a lot of trash really, but Mummy says their economy desperately needs tourism…”

Siân was a snob, but she was okay, so long as you let her talk about herself. At least I could be sure she wasn’t going to ask me what I’d done over the holidays.

“…and then we had to go to Bangkok in a hurry—Daddy’s business again—and then before you could blink we were off again to Sydney. There was a marvelous production of Tannhäuser at the Opera…”

I didn’t have to do much, just nod or grunt at the pauses. Her holiday was turning into a real world tour, but at least I didn’t have to make up any lies about being a Saxon serf.

The bus came, we got on and sat together, and her chatter continued.

“…and in San Francisco we met up with some old college friends of Mummy’s—the Coulsons—he’s in cybernetics and she’s a neurotronic psychiatrist…”

So, Siân’s folks were well connected to get the best for their daughter.

“…and I must have picked up a bug somewhere on my travels, and I had to spend a couple of days in hospital…”

There it was, that was the revision.

“…but I got a simply lovely private recovery suite, Tania, and the travel insurance paid for it.”

No—Mummy and Daddy have deep pockets, Siân, dear, but it would be so crass to mention it. Oops, I just did, didn’t I, Mister Zog? Will you forgive Tania a little envy?

“Oh, and Tania, I did think of you while I was there. It got so lonely, but then I’d think of you stuck in this ghastly hole of a village and I didn’t mind so much. And when I got out, Mummy took me shopping in Haight-Ashbury and I bought you this genuine Grateful Dead ‘Wake of the Flood’ tour button—really rare, they said, but I know you’re into the 1970s. I hope you like it.”

I was really touched. Well, sort of. Siân had thought of another person, however briefly, and she had even paused in her monologue to let me acknowledge it.

“Thank you, Siân, that’s so kind of you. And it’s lovely.”

Well, it was. Just totally inappropriate, given my own summer, but she wasn’t to know that. And I’d sworn to tell nobody about the theme park. So I smiled. Noblesse oblige, and all that. I mean, she’s just a robot doing her best, so how could I knock her down?

Senior school, I soon learned, is pretty awful. It’s not like first school, where the parents are just around the corner and close enough to take a real interest in their child’s progress. By the time we get to big school, a lot of parents are getting weary of the whole charade, and they let the school do what they want. In the case of the Lady Maud High School for Girls, they do still care somewhat, but most of the inner-city schools are pretty bad, I hear.

Lady Maud was a wealthy Victorian widow, we learned, who had used much of her late husband’s copper fortune to endow a modest school “for young ladies of whatever social class that do display an aptitude for learning… so that all God’s gifts in them shall be nurtured to the fullest degree.” Successive governments had recognized the worthiness of that Good Lady’s earnest intentions, and had invested taxpayers’ money to create a school that had hovered just outside the very top academic bracket for a little over a century.

But educating robots was not a government priority, and didn’t the teachers know it. The school was falling into ruin. Some of the buildings were boarded up, and I could see holes in the roof of one block. When we gathered for assembly in Main Hall, we rattled around in a cavernous space built to hold twice our number.

The Head Mistress—Mrs. Golightly—welcomed us to Lady Maud’s. She—Mrs. Golightly—spoke briefly about the Great Traditions of the School, about our Oxbridge Achievements and the Daughters of the School who had achieved High Office or other Greatness. She spoke like that, too. I mean, you could hear the capital letters. Once or twice I swear I could almost see them.

“She said the same thing last year,” whispered a voice from behind me.

“Word for word,” agreed her neighbor.

“The rest should be pretty short, then.”

It was. Mrs. Golightly trotted perfunctorily through her set speech and then abandoned us in some haste. Our Form Mistress gathered us up and led us to our classroom. Miss Gerrard introduced herself to us.

“I’m Miss Gerrard, but you must call me—and any other teacher—ma’am. Or sir, in the case of Mr. Cuthbert, our chemistry master here at Lady Maud’s. Lady Maud’s is a great school, with a fine academic tradition, and though times may change, we expect our girls”—she paused slightly at the word—“to perform to their highest while they are in our care. Others may fall by the wayside”—and what did that mean?—“but our girls are our only priority.…”

There was more, but the message was there, hidden just beneath the surface. Lady Maud’s might promise much for her human charges, but the robots were of no interest.

And so we began. English, geography, music, divinity, French. Latin, craft, and maths. That was Monday. I turned it into a little rhyme, to help me remember where I had to go.

English, Geog

Mus, Div, Frog

Lat’n, Craft’n’ Maths

Perhaps not very complimentary to the French, but it had a cadence and I found I couldn’t get it out of my head.

English. Mrs. Philpott, short and dumpy, and we quickly discovered, excessively short-sighted. But she loved her Shakespeare, and in our first lesson we found ourselves reading The Merchant of Venice.

Geography. Mrs. Hanson. Wispy and ethereal. She started to teach us about Africa. Mud huts and grass roofs. Dark-skinned babies, emaciated and dying. I put my hand up.

“But, ma’am, surely it’s not like that now?”

She coughed, embarrassed.

“No, quite right. Not since the Troubles. There are a few coastal enclaves left as I’ve described. But Africa has gone wild, and nobody really knows anymore what it’s like in the interior. Oxted’s invention solved the problem in the West, but there weren’t enough robots for Africa, and perhaps they wouldn’t have wanted them. Many tribes, many peoples, so proud.… So often stronger than the developed world. They face death better than we do.…”

Her voice tailed off. Her knuckles were white where she gripped the back of a chair, and her eyes glistened. I wondered what she saw. The silence lengthened and we fidgeted, looking at one another and all around. There were photographs at the back of the class, I noticed, of a young woman, who could have been a much younger Mrs. Hanson, in sun hat, tropical shorts, and blouse. Many showed her with children, brightly dressed and with beautiful smiles. In a few, she was visiting wards of a hospital, and the children looked unwell. In just one, set apart from the others, she was standing next to a tall, close-shaven black man. He was naked, except for a loincloth, but in his left hand he carried a short spear and an oval shield faced with hide, in the Zulu style. Very handsome, I thought. Mrs. Hanson clearly thought the same, for she was nestled under his right arm, and her left arm was about his waist. Husband and wife? I risked a glance at Mrs. Hanson, still staring far beyond the classroom.

The moment passed, and Mrs. Hanson continued.

“That’s enough. Back to life in the Kimberley Corridor, which is what we’re studying today.…”

Music. Miss Carr. Divinity. Mrs. Reese. French. Madame Lebrun.

They’re all old, I discover. They must have been teaching all their lives… and don’t know how to stop, even though there are hardly any real children left to teach. I realize it was like that at the village school, too, but I never thought about it. Are there no young teachers?

Boy, oh, boy, Mister Zog. What else have I never noticed?

Saturday, September 11, 2049

Saturday already, a whole week at Lady M’s. Suddenly this is my new normality—how does that happen? Siân Fuller’s practically my best friend. I mean, if she were human, she’d be a total airhead. But for a robot, she’s all right. I remember only last Wednesday I helped her do her homework on the bus. I smiled at the ridiculousness of it—when she wasn’t looking—for what’s the point of a robot learning French verbs? But I don’t follow that thought often, because it leads to the future, and the future is a very scary place, with too many unanswerable questions:

What happens to robots when they grow up?

Why does Mrs. Hanson have a photograph of a handsome Zulu warrior—her husband?—in the classroom?

Why aren’t there any young teachers?

What lies in the heart of Africa, beyond the Kimberley Corridor?

Why hasn’t John called me?

Yes, why hasn’t he called?

I dreamed about him last night. That single, daring peck on the cheek. The memory makes me feel all hot inside. I’m embarrassed, I suppose.

He hasn’t called me. Not in nearly two weeks since the holiday ended. Has he forgotten me so quickly? Has he lost my PTI?

English. We’re reading Shakespeare. Sorry, I think I already said that. Yes, I did. The Merchant of Venice. Mrs. Philpott. We played tricks on her. Moved things when she wasn’t looking, so she couldn’t find them. Her sight is very bad.

But she knew her Shakespeare by heart, and she never needed the books we hid. After a while we gave up our tricks—it was no fun.

Mostly we just read our lines in a bored monotone, and she’d say things like “No, no, no, imagine this is happening to you. How would you feel, dear?” And then her victim would briefly display anguish or ecstasy, with all the range and the depth and the sincerity that an eleven-year-old can muster, which is not a lot, Mister Zog. And then she’d say, “That’s so much better,” while rolling her eyes up to heaven.

And then, of course, it was suddenly my turn to read Portia, Mrs. Philpott’s exhortation still fresh—“How would you feel, dear?”

How all the other passions fleet to air:

As doubtful thoughts, and rash-embrac’d despair,

And shudd’ring fear, and green-eyed jealousy!

O love, be moderate, allay thy ecstasy,

In measure rain thy joy, scant this excess!

I feel too much thy blessing: make it less

For fear I surfeit

Is this the trickery of Shakespeare that suddenly from nowhere an image lodges in your brain? A ginger-haired boy dressed in ’70s clothing, dancing to a Slade tribute band?

Mrs. Philpott said nothing, but I felt her eyes on me long after I stopped and Bassanio spoke. At the end of the lesson, she kept me back for a moment.

“You felt something.”

It wasn’t a question, and I felt I could trust Mrs. Philpott.

“I did. There’s someone…”

“Yes, I thought there might be. That’s how it often begins. Our experience brings life to the words. The words enrich our experience.”

“How it begins, Mrs. Philpott?”

“Our love affair with language, Miss Deeley. How dull to be an animal, knowing only emotions, or a drab mechanical, knowing only words. To be human is to feel, which is to give expression and texture to our emotions through language.”

“Is that all?”

“It’s everything, Miss Deeley. Does flesh and blood define humanity? I disbelieve it. Many born of woman do not feel— look at history and ask yourself, could this man or that have acted that way, if he could truly feel?”

“You mean, like Hitler?”

“An extreme example, but yes. A man born of woman, I grant, but human?”

“I…”

“A rhetorical question. Don’t answer. In act three, scene one, there’s a famous speech by Shylock, claiming his own humanity— ‘I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes?’—and thereafter going on to define his humanity in purely physiological terms. Then read his actions. Does he use language to leave the prison of his own head, and understand the feelings of another human? Does he, therefore, love another human more than himself? Or do his actions and his language show that he is alone, locked within his own mind?”

I think she would have gone on more, but I was fidgeting, nervous that I’d be late for my next class. She told me to run along.

I was going to take the play home and read it, but I forgot to put it in my homework bag. But later I remembered, and I cheated. I went and found an old mpeg on the TeraNet and watched Anthony Sher as Shylock. Is Shylock human? By Mrs. Philpott’s definition, probably not.

But I’m going to watch that mpeg again. And again. And I promise I’ll read it, too.

I’ve decided I do love language.

I’m glad I’m human.

Monday, September 27, 2049

I heard from John.

He’s fine, he says. Enjoying school. How am I?

“I’m fine, too.” Why didn’t you call me? “It’s nice to hear from you.”

“Uh, yeah.”

You can do better than that. Typical boy! “You must have been very busy.”

“Uh, not really.”

I hope you didn’t call me just to grunt. I remember you used to talk. Back in the 1970s. “Well, I’m glad you didn’t lose my PTI. I was beginning to think you were just going to be a holiday memory.”

“No, I wanted to call you.” It constructs a whole sentence! “But I felt awkward. Afraid you might…”

“What?”

“Not like me anymore.”

“That’s silly, John. I like you a lot.”

“And I like you a lot too, Tania.” Go on, go on! “I… I… yeah, I like you a lot.”

Gosh, you’re really communicating today, John. I’m going to have to do some serious work to get anywhere. “I thought a lot about our holiday, you know, John. Making friends like that hasn’t happened to me before. All the people I know are, like, the kids of my parents’ friends, my dad’s parishioners’ kids, and the kids in my class. I’ve never really had a choice in my friends. They’re just there, and I accept it. You’re different.”

“Uh, thanks.” Don’t grunt! And try constructing complete sentences. “It’s the same at my school, I suppose. I watch the others run around playing soccer, and there’s a part of me thinking that they’re just programmed to do that. It’s not fun they’re having, it’s just the way they’re made. So I don’t want to join in. I don’t have any friends. Not really.”

“You mean, because they’re all robots.”

“Yeah.” I forgive you for grunting, this time. My own fault for asking a boy a yes-or-no question. And the rest wasn’t bad for a boy, either. Lots of sentences. We’ll try for a few adjectives, next time.

“So you do understand. I never felt the same as the others at school. There’s always the knowledge that they’re different. I never wondered how I’d ever recognize a human kid if I met one. I knew they’d stand out. I just worried that it might take a long time to happen.”

“And now?”

“Now it has happened. I’m very, very happy. So talk to me some more, and don’t spoil it.…”

Anyway, Mister Zog, that’s enough. I think there are one or two things I still want to keep secret from you, at least for the time being.

Tuesday, October 26, 2049

My foot.

My foot.

I’m staring at my foot, like it doesn’t belong to me.

My traitorous foot.

I’ve been sitting in my room now, for an hour or two. Longer, maybe. Mum and Dad have been up, telling me once more that they still love me, but I’m not talking to them, and they’ve gone away again. If I concentrate, I can hear them downstairs, whispering, crying, pacing up and down. I try not to listen, though. It doesn’t help. I just sit here, staring at my traitorous foot, while my thoughts whirl in mad circles.

If only…

The first If Only:

If only I hadn’t let Siân talk me into a trip to London at half term.

“It’ll be lovely,” she said. “Mummy and Daddy will take us both in the Mercedes—there’s lots of room—and we’ll visit the Tower of London, and the London Eye and HMS Belfast and Madame Tussauds, and we’ll stay in a hotel and…”

That was Siân all over. She couldn’t stop talking. Ever.

But it sounded like fun, so I said yes.

The second If Only:

If only I hadn’t decided to show off.

We’d been round HMS Belfast, with its bow guns still trained on Barnet. Why Barnet? You’d think it would be more use to aim at a Yellow or Red Zone. Well, Siân had chased me round the decks, and I’d hidden from her, and jumped out and surprised her. And then we’d turned about while I’d chased her.

Harmless stuff.

And then we’d crossed Tower Bridge and watched the boats ply up and down the Thames, and ended up at the Tower of London. It had been restored a few years ago, to mark the 500th anniversary of Anne Boleyn’s execution. The moat had been re-excavated, and turned into a boating environment for tourists, complete with a picnic park. They were running 3-Dram pictures of the pageant, with robot actors playing Boleyn and her executioner, Jean Rombaud, and stills of old King William officially opening the Gate and then being rowed out to the river. But mostly what Siân and I were interested in was more chasing games, hide-and-seek.

We ran out of places to hide.

At least, if we stayed in the public areas.

So we didn’t. While Siân’s back was turned, I raced off toward Traitor’s Gate. They run boat trips nowadays, with theme parties where people dress up as condemned nobles on their way to the Tower, but only in summer. So it was all off-limits now, and the tour boats bobbed gently, chained up at the base of the steps.

I climbed over the low gate and pattered down the steps to the waterline, but now I was here, there really wasn’t anywhere to hide. Except down with the boats, and I could hear Siân running closer, so I scrabbled in, and slid under a tarpaulin. The skiff rocked rather wildly as I did so, but I just stayed low and it steadied.

There were a few bumps, and I risked a peek out from under the tarpaulin.

The first thing I saw was Siân looking right at me, and as she saw my face emerge, her own expression became surprise, then horror, and she pointed at me and shrieked.

And then I looked about me, to see what the fuss was about, and there was muddy water in every direction. The little skiff was drifting away from the steps, caught by the eddies, and heading out toward the river.

Oops!

No oars, I quickly discovered, and the first gate was past, too far to reach. Siân had summoned help—a Beefeater—and he was casting off a second skiff. But it wasn’t going to be in time; my own skiff was moving faster, toward the open river. Beyond the arch of the river gate, the Thames was racing past, and there were some iron railings partway across. The skiff would miss them, but not by much, so perhaps I could jump across…

Behind me, the Beefeater was rowing, calling something as he rowed…

“Don’t jump!”

…but the railings were close, and I knew I could make it.…

I jumped…

The third If Only:

If only my foot hadn’t caught in something as I jumped.

I felt something wrap round my ankle, just as I also realized you shouldn’t jump from an unladen skiff. As I pushed off, the boat simply spun out from under me and I went down into the water.

And that something wrapped tight around my ankle pulled me down, held me down. I reached down with my hand, and felt a tangled mass of rope, and chain, tight and pulling me ever deeper.

I opened my eyes, but the murky water showed nothing clearly. There was a pressure in my ears, so I knew I must be going deep. And I could feel a terrible burning in my chest—I was going to have to take a breath and then it would all be up with me. I’m not sure if I managed a clear thought then, but perhaps I might have thought, “Good-bye” or “Sorry” or “I love you, Mum and Dad.” Maybe a bit of each…

The fourth If Only:

If only I’d drowned.

I couldn’t stop myself from taking that breath. I knew it would kill me, but I did it anyway.…

There was a curious sensation as the water rushed into my lungs. Only that. Just curious. There was no choking feeling. Nothing, except maybe a slight resistance as I breathed.

I was breathing. Breathing water. I could feel the motion of my chest as I breathed out again, and in. I wasn’t dying.

Then through the murk came a figure, swimming. The Beefeater, I supposed. And he had a knife, because I felt a sawing around my foot, hacking, hacking, cutting through the rope that held me.

It was enough. My foot came free and I struck for the surface, feeling the strong arms of the Beefeater bearing me up.

I’m not sure exactly what happened then, but I remember flashes:

My head breaking water, and I coughed out a little water…

Hands, hauling me out of the water…

Siân, bending over me as I lay, her eyes flicking down, not quite meeting my own…

More hands, lifting me onto a stretcher…

A brief glance at my feet, still hurting…

My right foot, bloody where the knife had slashed…

And something else: silver-gray threads, shimmery and bright…

Silver-gray threads…

Silver-gray threads…

My next clear thought was some time later, when I realized the white blur in front of my eyes was a ceiling, and I was lying on my back, in a bed.

A hospital bed. Obviously.

I sat up, half-expecting resistance from bandages and drips and I don’t know what else. But no, the covers fell away from me easily, and I flicked the sheet off the bottom of my bed, to see…

My foot—both feet—sticking out of the end of a pair of green-striped hospital pajamas.

Perfect.

Not a mark. Not a scratch. Not a blemish.

I leaned forward to inspect them more closely. If either of them had been hacked bloody with a knife, I couldn’t prove it. I touched each foot, carefully.

Healed, I thought.

No. Not healed.

Repaired.

A memory rose, unbidden, of a name.

Martin.

Perhaps I said it aloud, perhaps I only thought the words.

I am a robot.

{Memory}

Martin.

We went on holiday with one of Dad’s friends a couple of

years back, and it was awful. You could tell he didn’t like children, but his wife was besotted with their little kid. The kid’s name was Martin, and he was a ghastly brat. A boy, but his father made no secret that it was a robot—at best just a little too much stress on the second syllable of the name, but occasionally cruel little remarks about “Tin Boy”—and every time she overheard him, his wife looked ready to kill him.

Boy, do you meet some weirdos…

That was a holiday in Wales, which is a funny place, all mountains and terraced houses made out of real concrete— really traditional. So passé. Of course, New Cardiff is properly modern, built out of proper repolymerised PET. But we weren’t staying there. We were in some ghastly hole called Abersomething—all double-l’s and double-d’s and y’s—which was at the bottom of a valley so deep the gigahertz broadcasts couldn’t get in. A whole week with no vid. Well, there was sort of, and Dad said that the brochure hadn’t completely lied, but the signal was so weak—Dad put on a tech-sales voice and called it at-ten-u-a-ted—that you could only get color or 3-D, not both.

Anyway, my point was that Aber-double-l’s barely had electricity, let alone TeraNet. It was primitive and dangerous. So when Martin the ghastly brat went for a walk along the beach, it should have been no surprise to anybody when he tumbled off a rock and landed in a pool of seawater.

The first I knew something was wrong, was when I heard this eerie screaming sound, not loud, but insistent, and it set my teeth on edge. I’d not seen him fall, but I had a pretty good idea where the sound was coming from, and I knew immediately that Martin was in trouble.

I scrambled over the rocks, yelling for the adults to come and help, even before I saw Martin. When I did, I thought I was going to faint. I’d expected to see blood—robots are designed to bleed—but he’d fallen onto a spur of rock, and it had gouged a hole in his side.

What showed was nothing so crude as gears and rods, but tightly packed micro-servos, pseudo-organic tensors, and weaving throughout were the silver-gray threads of Oxted’s marvellous creation, the neurotronic web.

Martin wasn’t moving, and the scream that had summoned me was now just a low moan. I looked back, but the adults were still sitting calmly around their picnic, unaware that anything had happened. So I yelled—quite a bit—until they got the idea that something serious had occurred, and I turned back to Martin.

The web was still bright, which was a good sign; if the web lost its silver shimmer and turned gray, then it would be all over for Martin. But what to do? How do you help an injured robot? They don’t teach that in my village school. I decided to lift him out of the water a little—the saltiness couldn’t be good for him.

It was hard work, but I’m fairly tough for my age, and I managed to haul him up far enough that the water could drain out of the wound. There was quite a bit of gray now, I couldn’t help noticing, but still a few sparkles.

Then the adults arrived, all puffing and out of breath. Don and Suzie were completely useless; Suzie just sat down like she’d been sandbagged and went into shock, and Don tried to comfort her. So Mum and Dad had to carry Martin back along the beach to the car. Behind me I heard Suzie moan and mutter, and before you could say “Oxted’s web” there was a blazing row with Suzie blaming Don for not protecting their son, and Don saying it could be mended.

We tried the doctor in Aber-double-l’s. He was an old man, near retirement, I suppose, and though he’d converted to dualpractice (of course), you could see that he wasn’t really comfortable with robot patients. His hands were shaky, too, and that’s not good for a neurotronic web. The silver streaks were going grayer. So the doctor asked the inevitable.

And that’s when Suzie really threw a wobbly.

Backups.

There weren’t any. At least, nothing from the last three years.

And Doctor Evans didn’t want to risk taking a fresh backup at this time—his downloader was an old model, he said, and he wasn’t sure it could handle Martin’s data rate—there could be data corruption, even if there was still enough of a pattern to copy.…

But Suzie wasn’t listening. She was just screaming at Don for neglecting Martin’s backups, and how he knew she wasn’t technical and he should have done them and he hated Martin and…

Poor Martin. They got him fixed, but like I said, the last backup was three years old.…

So Martin lost the last three years of his memory. A five-year-old mind in an eight-year-old’s body.

Don and Suzie sent us separate Christmas cards last year. Martin wasn’t mentioned on either. I guess they sent him back to Oxted.

The Uncanny Valley.

Is that where I am, now?

Interval 2

This is brilliant material, Tania, though I don’t suppose you appreciate my professional glee. You’re right about me being an archaeologist, but I’m a psychologist, too, and you can add anthropologist, to round out your picture of me. Yes, just one alien, doing all that.

The truth is, we’re not a numerous race, nor do we have huge space vessels to courier us across the galaxy at FTL speeds. The universe is stingy with the exotic forms of matter we need even to move at the speed of light, so six crew is about the maximum, and we split all the jobs between us.

I had to pull strings to get this expedition to happen. The Directors— the leaders of my people—disliked the idea of sending a precious ship all the way to Dawn. The Dawn Civilization has been studied to death. We should be moving out—by which they mean moving in, toward the galactic center, where the stars are more numerous—in search of new life.

And if we meet such life, I replied, how shall we introduce ourselves? Hello, we are the Old People, the Bored People, the Tired People. We have so little vigor, you see, Tania. I convinced them that a fresh study of the Dawn Civilization might teach us how to be young again.

Perhaps I lied. Perhaps this expedition is all about my personal vanity and relief of ennui. I hope not. I need you to teach my race how to restore ourselves.

Tuesday, October 26, 2049

Michael and Annette had been waiting quietly outside my room; when I called a tentative hello they entered.

They… shuffled. Heads slightly bowed, so they didn’t have to meet my eyes. Annette’s face was red and her eyes puffy—she’d been crying. Michael just looked totally hangdog and guilt-ridden. He broke the silence.

“How are you?”

“Not dead. Unfortunately.”

“Ah.”

And that was the confirmation. Not “How could you say such a thing?” or “Oh my darling little girl.” Just “Ah.” Shorter than “Oh, dear, now you know we’ve been lying to you all your life”— but it meant the same thing.

“What do I call you now? Michael? Annette? Reverend Deeley? Mrs. Deeley?”

“We were hoping you’d still call us Mum and Dad.”

“But you’re not, are you?”

“Perhaps not in the biological sense, no. But we’ve given you all our love, always. If we could have had a child, we couldn’t have loved her any more than we’ve loved you. I feel I am your dad, in every way that matters. And Mum, she feels the same way about you.”

“You let me believe I was special. Human.”

“You are special.…”

“Just not human.”

Annette looked up then, and she said her first words.

“They send you on a course, you know. When you decide… You know. Oxted.”

I could have said something to help her in her difficulty, but I was feeling hurt, and so I wanted to hurt them. So I kept silent and let her struggle to find some words.

“It’s all about what to tell your new child. They tell you it won’t work, unless you think of your new baby as human. You mustn’t think of it as a robot, they say, and you mustn’t tell it that it’s a robot, because if you do, it won’t develop properly, it won’t reach its best potential.”

“That’s right, Tania,” added Michael. “After the first few weeks, we never thought of you as anything else. You were our little miracle, a real child in a barren world. As far as we could, we avoided anything that might break the spell.…”

“That’s nonsense,” I blurted, wanting to puncture Michael’s lie. “What about my revisions? What about backups? You’re supposed to take a backup. Regular backups. Remember Mar-tin?”

They looked at each other, and it was Michael who answered me.

“Yes, I’d forgotten you were there when Martin was injured. Your mum and I never did take backups. It was a conscious choice. If we’d had a… a child of our own bodies”—Michael stumbled, trying to avoid the word “real”—“we’d not have been able to back her up. And so with you. If you’d been badly injured, we’d have lost you. Completely. If you’d died, part of us would die, too. Without the risk of loss, there cannot be genuine love.”

Was that the vicar speaking, with a scholar’s reasoning? It sounded like something out of one of his sermons, crafted and pithy. And it must have made sense to Annette, because she was nodding agreement, but I didn’t understand it one little bit. To love something more, you safeguard it less?

“Look, Tania. We know what’s happened has been a shock to you, and your mum and I are upset, too. But you’re part of the family…”

Like the butler. Soames, the stupid, clumsy robot that still crushes ping-pong balls.

“…and families survive far worse than this. We stay together. Nothing changes.”

How’s that? Yesterday I was a girl. Rare and wonderful. Today, I’m a robot. A production-line pet, constructed to comfort two humans who can’t have a real child of their own.

“Tania? Tania?”

I realized I’d drifted off, my mind somewhere else. Without thinking, I replied, “Yes, Dad?”

I didn’t mean to use that word. It wasn’t part of my plan.

Oxted had made me too well, because then I cried.

Expiration Day © William Campbell Powell, 2014