In this biweekly series, we’re exploring the evolution of both major and minor figures in Tolkien’s legendarium, tracing the transformations of these characters through drafts and early manuscripts through to the finished work. This week’s installment takes a look at Elanor Gamgee, the eldest daughter of Samwise and Rosie.

Elanor Gamgee, eldest daughter of Sam and Rose, gets little enough exposure in The Lord of the Rings. We know she is born on March 25, the first day of the new year according to the Gondorian calendar, and of course the date of the Fall of Sauron. Her name is Elvish in origin. In fact, Sam and Frodo name her together, after the “sun-star” flower they saw in Lothlórien, because (as Frodo says) “Half the maidchildren in the Shire are called by” flower names. Sam hints that he wanted to name her after someone they met in their travels, but admits that such names are “a bit too grand for daily wear and tear.”

The Gaffer, perhaps alarmed by some of Sam’s outlandish suggestions (or so I like to imagine), insists that it be short and to the point. But Sam himself just wants it to be a beautiful name: for she takes “‘after Rose more than me, luckily,’” and “‘you see, I think she is very beautiful, and is going to be beautifuller still’” (VI.ix.1026).

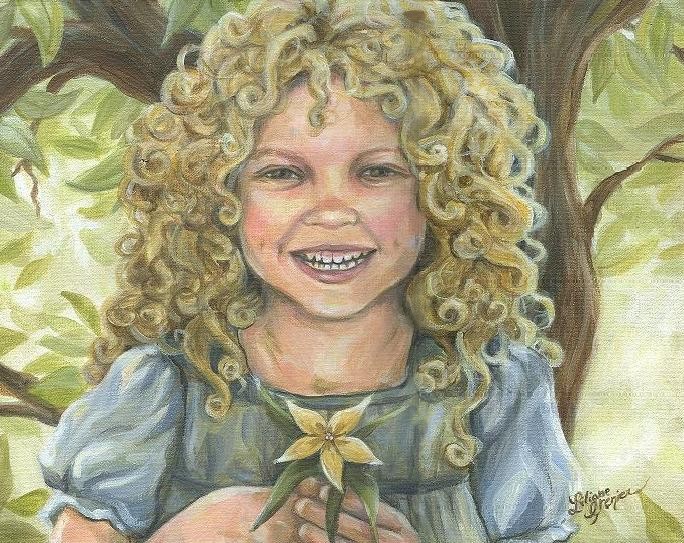

That is, sadly, all that Tolkien tells us about Elanor in the main text of The Lord of the Rings. The Appendices, thankfully, give us a little more information, so let’s turn there. One footnote to the “Chronology of the Westlands” (Appendix B) describes Elanor thus: “She became known as ‘the Fair’ because of her beauty; many said that she looked more like an elf-maid than a hobbit. She had golden hair, which had been very rare in the Shire; but two others of Samwise’s daughters were also golden-haired, and so were many of the children born at this time” (Appendix B 1096). Later, at age 15, Elanor meets King Aragorn and Queen Arwen for the first time when the royal party comes to Brandywine Bridge, and there Elanor “is made a maid of honour” to the queen (Appendix B 1097).

In the Shire Year 1442, Sam and Rose and Elanor (but apparently not any of the other children?) stay for an entire year in Gondor. It is after this in the timeline that Elanor is first called “the Fair”; it might very well be, then, that she receives this title in Gondor (Appendix B 1097). In her thirtieth year Elanor marries a hobbit (presumably) by the name of Fastred of Greenholm. They name their first child Elfstan Fairbairn, which must have caused quite a stir among good, decent hobbit-folk. Pippin, at Sam’s request, names Fastred “Warden of Westmarch,” and the small family goes to live “at Undertowers on the Tower Hills, where their descendants, the Fairbairns of the Towers, dwelt for many generations” (Appendix B 1097).

The last we hear of Elanor Gamgee Fairbairn is that, after the death of Rose, she sees her father off to the Grey Havens on September 22, 1482. Sam gives her the Red Book, which is cherished by her family, and she in turn cultivates the tradition “that Samwise passed the Towers, and went down to the Grey Havens, and passed over the Sea, last of the Ring-bearers” (Appendix B 1097). As Frodo had foreseen on the eve of his own departure from Middle-earth, Sam was indeed made “solid and whole” again (VI.ix.1026), and was finally reunited with his beloved Mr. Frodo.

All this certainly gives us some sense of who Elanor was. Clearly, Sam and his family didn’t live lives as quietly retired as Frodo on his return; rather, they seem to have celebrated the striking sense of difference that entered their family through Sam’s travels. And while I’m sure their antics must have raised some eyebrows among the steady sort, it seems to have done the Shire a world of good. After all, they did elect Sam Gamgee mayor for seven consecutive terms.

Luckily for us, we aren’t left solely with this scanty information about Elanor. She gets a front-and-center role in Tolkien’s drafts of an unpublished epilogue to The Lord of the Rings that tells us quite a bit about how Tolkien himself envisioned her. We should remember, before embarking on such a quest, that the epilogues can’t strictly be considered canon since they weren’t published by Tolkien himself, and so be careful with our judgements. Regardless, the picture of Elanor in those drafts is relatively stable, and Tolkien himself desperately wished that he could have added “something on Samwise and Elanor” (Sauron Defeated, hereafter SD, 133), so we might just be able to learn something to our advantage.

Buy the Book

The Witness for the Dead

Indeed, the first draft of what we now call the epilogue was meant to be part of the main text itself, continuing straight on from Sam’s words, “Well, I’m back,” that now bring the story to a close (SD 114). In this draft, Elanor, sometimes called Ellie, is 15 and is questioning her father about the flower for which she was named. She has a great longing to see it, telling her dad (and for readers fondly recalling Sam’s own wishes in the early pages of The Lord of the Rings), “‘I want to see Elves, dad, and I want to see my own flower’” (SD 115). Sam assures her that one day she might.

It also comes out in this draft (which is staged as a sort of question-and-answer session between Sam and his children, in order to let readers know what became of the other characters), that Sam is teaching his children to read. Elanor, it seems, can read already, for she makes comments about the letter that has come from King Elessar.

After this version of the text, the story transformed slightly, and did in fact become an “Epilogue” in name (and it’s this text which has been newly illustrated by artist Molly Knox Ostertag). While the first draft is in many ways the same as the one we just discussed, the second draft of the Epilogue changes dramatically. Here, Sam and Elanor are alone in his study; it is Elanor’s birthday, and earlier in the evening Sam finished reading the Red Book to the family yet again (SD 122). Elanor mentions that she has heard the entirety of the Red Book three separate times (SD 122). Sam shows her a sheet of paper which she says “looks like Questions and Answers,” and indeed it is.

Here, we get a slightly more clumsy version of what felt more natural in the first version: an explanation of what happened to other characters, and answers to remaining questions the reader might have. Tolkien, I think, understood this at the time, for he puts words in Sam’s mouth that probably reflected his own concerns: “‘It isn’t fit to go in the Book like that,’” he sighs. “‘It isn’t a bit like the story as Mr. Frodo wrote it. But I shall have to make a chapter or two in proper style, somehow” (SD 123-124).

In this draft, however, Elanor as a character is more fleshed out, and we see both her own natural understanding and her fondness for her father. Already, Elanor has a sense of the changing world outside, though at this point she has seen little enough of it. She worries that she won’t ever get to see Elves or her flower: “‘I was afraid they were all sailing away, Sam-dad. Then soon there would be none here; and then everywhere would be just places, and […] the light would have faded’” (SD 124). Grim thoughts for a young hobbit-child, but Sam sadly agrees that she sees things correctly. But, he adds, Elanor herself carries some of that light, and so it won’t ever go out completely so long as he has her around.

It is at this point that Elanor, thoughtful and quiet, admits to finally understanding the pain that Celeborn must have felt when he lost Galadriel—and Sam, when he lost Frodo. She seems here to understand her father quite well—they clearly have a special relationship, illustrated both by their pet names for each other (Sam-dad and Elanorellë), and by Elanor’s deep empathy for her father’s lingering sadness. The moment is touching, and Sam, greatly moved, reveals a secret that he has “never told before to no one, nor put in the Book yet” (SD 125): Frodo promised that one day, Sam himself would cross the Sea. “‘I can wait,’” Sam says. “‘I think maybe we haven’t said farewell for good’” (SD 125). Elanor, in a flash of insight, responds gently: “‘And when you’re tired, you will go, Sam-dad. […] Then I shall go with you’” (SD 125). Sam is less certain, but he what he tells her is fascinating: “‘The choice of Lúthien and Arwen comes to many, Elanorellë, or something like it; and it isn’t wise to choose before the time’” (SD 125).

It is, of course, impossible to know exactly what Sam (or Tolkien) meant by this, especially since the Epilogue ends soon after, and the “Chronology of the Westlands” tells us nothing more about this idea in particular. It could simply be evidence of Sam’s wishful thinking—a faint hope that he wouldn’t have to ever be parted from his daughter.

Whatever Sam meant, it is clear that Elanor is more elvish than any hobbit child has a right to be. In this, Elanor seems to me to be a sort of promise: Sam, and Middle-earth itself, have not lost the Elves entirely, though their physical forms are gone from the world’s immediate circle. Tolkien’s Elves are, after all, very much tied to the earth and its fate. And, as The Hobbit insists, “Still elves they were and remain, and that is Good People” (168)—which suggests to me that we might still get a glimpse of elvish power in the goodness and kindness of those around us.

Elanor, then, takes after her mother in more ways than one: even more vividly than Rosie, she demonstrates the wonder of everyday miracles. She embodies the gifts that fantasy and imagination offer us: a transformed, renewed vision of the good in our own world. Elanor reminds us to take the wonder of Middle-earth with us when we go, and to let it grace our interactions and restore our hope.

Megan N. Fontenot is a dedicated Tolkien scholar and fan who is once again amazed by the richness of Tolkien’s imagination. Catch her on Twitter @MeganNFontenot1 and feel free to request a favorite character while you’re there!

Love this!! Elvendom still present in Middle-Earth in a Hobbit-Maiden.

Thank you for another wonderful article, Megan. Really appreciate and enjoy your insights and interpretations in this series.

Doesn’t Elanor serve as a lady in waiting to Queen Arwen, or did I imagine reading that?

This is fitting in light of the other previous article and I enjoyed reading it. Was it inspired in some way, or did you always have a plan to write about Elanor?

She definitely has some of that deep thoughtfulness that I think sets Sam apart in some ways (even if they still are salt-of-the-earth types). Maybe a touch of…melancholy or gothiness isn’t really the right word, but she sees a little deeper and has some idea of the sorrow that can underly things (perhaps she is a bit Nienna-like here ;) ).

I totally forgot her husband was named a warden at ‘Sam’s request’. Heh, a little nepotism here? But one must assume he was qualified as I doubt Sam would really throw his weight around that way.

Two things.

1. Blonde children in Sam’s line and in other families throughout the Shire makes me wonder if there wasn’t an Elven milkman around for a few years.

2. (SD 125). Elanor, in a flash of insight, responds gently: “‘And when you’re tired, you will go, Sam-dad. […] Then I shall go with you’” (SD 125). Sam is less certain, but he what he tells her is fascinating: “‘The choice of Lúthien and Arwen comes to many, Elanorellë, or something like it; and it isn’t wise to choose before the time’” (SD 125).

The key to #2 I think is the part of the line “or something like it”. Elves, when they make the decision to choose immortality or mortality, are making a life-altering decision in so many ways. I think he is cautioning Elanor to not be hasty in her choices, to live her life and not his. She’s far too young a Hobbit to be making life choices yet.

Sam is clearly anticipating Elanor leaving him for a husband, as daughters do, and doesn’t want her to cut herself off from the possibility of a family of her own.

These pieces are bittersweet; one can sense JRR writing that with his own memories of the Great War, appreciating what he had (“I am a very rich hobbit”) and thinking of his peers who did not come back from the war.

@@@@@#5: It is implied that the influence of the soil from Galadriel’s Garden that she gave Sam in the little box (said box also had the Mallorn nut/seed), that Sam distributed up and down the Shire, was responsible for the blond/golden-haired children, and for making the Shire-Reckoning year 1420 a particularly special and bountiful year. Hence, for an example near and dear to my beer-loving homebrewing heart, the line about the barley being so good and so bountiful that year that in years to come, an old Gaffer would quaff a good mug of beer and say, “Aye, that’s a proper fourteen-twenty!”.

@5: I’m thinking “Shire of the Damned” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Village_of_the_Damned_(1995_film)

Although I have been known to call myself a Tolkien “fan,” I will confess that I have never read the entirety of the History of Middle-earth. Somehow, then, until this site recently posted Molly Knox Ostertag’s illustrated version, I had no idea that there was such a thing as the Epilogue.

As I read the text of the second version for the first time last week, it was as if catharsis I had needed for more years than I can count was finally complete. Oh, how I wish Tolkien had included it in LOTR! (Yes, yes, I know how pressed for time he was, and limited in number of pages). I still remember the huge shock and sense of being dropped empty-handed and empty-hearted (full-hearted, really, but I hope you know what I mean) when I reached the end of Return of the King. What! Surely it can’t end here? Wait, it does! But…but…but . . .

Having the Epilogue would have given us that subtle full circle in Sam’s own curiosity showing itself in Elanor and also preparing us for the bits of further history Tolkien did include in the Appendices. Anyway, I’m thankful to have this all rounded out now, even so many years later. And thank you, Megan for another fond and thoughtful presentation of a character from Middle-earth.