Ben Gold lives in dangerous times. Two generations ago, a virulent disease turned the population of most of North America into little more than beasts called Ferals. Some of those who survived took to the air, scratching out a living on airships and dirigibles soaring over the dangerous ground.

Ben has his own airship, a family heirloom, and has signed up to help a group of scientists looking for a cure. But that’s not as easy as it sounds, especially with a power-hungry air city looking to raid any nearby settlements.

To make matters worse, his airship, the only home he’s ever known, is stolen. Ben finds himself in Gastown, a city in the air recently conquered by belligerent and expansionist pirates. When events turn deadly, Ben must decide what really matters—whether to risk it all on a desperate chance for a better future or to truly remain on his own.

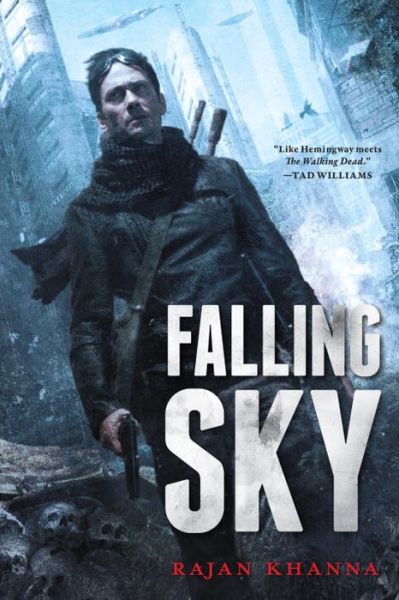

![]() Check out an excerpt from Rajan Khanna’s debut novel, Falling Sky—available October 7th from Prometheus Books.

Check out an excerpt from Rajan Khanna’s debut novel, Falling Sky—available October 7th from Prometheus Books.

CHAPTER ONE

It’s when I hit the ground that my skin starts to itch, as if I can catch the Bug from the very earth itself. I know I can’t, but I itch anyway, and the sweat starts trickling, which doesn’t help. But there’s no time to focus on any of that now because I’m on the ground and there’s nothing safe about that. So I heft the rifle in my hands, trying not to hold it too lightly, trying to feel a bit casual with its weight but the kind of casual that makes it easy to shoot.

And then Miranda is next to me. She gives me that half smile, that almost mocking look she always does, and I see the sun reflected in her glasses. Then she’s off, moving quickly to the prone form in the nearby clearing, the filthy, long-nailed mess I dropped just minutes ago with a tranq gun.

The fucking Feral.

It’s laid out in the grass, head lolling to the side. Not moving. Just the way I like them. Its hair is a tangled mess merging into its beard. Figures. Lone hunters are usually male. It wears a faded collared shirt so matted with dirt and muck that you can’t tell what color it might have originally been. Its pants are tatters. And the stench… I always wonder how Miranda can stand it.

There’s nothing about it that says who he might have been before. Someone’s brother? A father? A son?

All swept away by the Bug.

It occurs to me that if my dad were alive, he would be telling me how truly fucked this is. He was the one who taught me to run from the things. To keep to the air. But my dad isn’t around. Not anymore. And he’d be one to talk anyway.

As Miranda bends over the Feral, I catch sight of the pistol hanging from her belt in the makeshift holster. I gave her that pistol. Not that I ever want to see her have to use it. Especially not with the ammo supply being what it is. But she has one, and that’s at least one smart change I’ve made. The others… I’m still deciding.

My heart picks up in my chest the closer she gets to him. But that’s not the worst part. He’s out, and will be out for hours most likely with the dose I hit him with. He’s not going to wake up and grab her. No, what I’m afraid of comes next.

Miranda pulls out the syringe.

My breath almost stops.

She’s got the gloves on, the mask, and only the skin around her eyes is visible to me—another smart change I’ve made to the process—but we’re talking blood here. Feral blood. And if my dad taught me to run away from Ferals, he taught me to fly away from their blood. Because that’s how the Bug is transmitted. By fluids. And if Miranda were to swallow or maybe even inhale just a little of that Bugged-up plasma, well, there’ll be one more Feral in the world. And while Miranda pisses me the fuck off on a regular basis, I’d hate to see her go like that.

She has the syringe in his arm, and the blood glugs out into a tube. You’d be surprised at how few test tubes there are in the world. But then again, maybe not.

Just a moment more and we’re done, and Miranda will head back to the airship ladder and I’ll follow, making sure I give her a wide berth.

I’m getting antsy, feet ready to move, when I hear the first screams. The rifle raises in my hands almost of its own accord as I scan beyond her for the pack. “Miranda,” I call.

“Almost there.”

“Now,” I say. I can see the shapes moving down the next hill, Ferals loping over the grass in tattered clothing. Their howls echo across the space between us. Miranda still isn’t up.

Then yelps come from behind me. “Now!” I roar as another pack comes from the other direction, this one larger, and closer.

The rifle kicks back in my hands and gunshots punctuate their screams. I don’t worry about where they came from, why I didn’t see them. I breathe in, set up a shot, take it. Breathe out. Even after all these years, part of my body wants to jerk the trigger wildly, pepper the whole area with gunfire, but I don’t have the ammo for that, and I can’t afford to reload. And I’ve learned to control that part of me. Learned to push it into some dark corner of the soul. Or something.

The rifle bucks. One Feral goes down in a spray of blood that sends a chill through me. Another’s face explodes in a wet mess. Miranda runs by me, careful to stay out of my line of fire, and I smell that elusive scent of hers. Then she’s climbing up the ladder, and after another two shots I’m right behind her.

I try not to think about the vial of blood she’s holding. Try not to think about it falling on me, somehow breaking. I try and I fail.

A Feral reaches the bottom of the ladder, and we’re still not up to the ship. I hook my arm around the rope, and do the same for my leg. And I slowly aim and fire down on the thing’s head.

Then we’re moving up and away, Miranda at the controls of the Cherub, and the feel of the wind on my face, meters above the ground, is like a kiss.

Making sure the rifle is secured, I climb the rest of the way to the gondola.

The thing you have to understand for this to all make sense is that Miranda’s a little crazy. Back in the Clean, they would have called her idealistic, but back in the Clean idealistic wouldn’t have gotten you killed. Or maybe it would. I’ve never been too good at history.

Miranda’s crazy because she thinks she can cure the Bug. Not all by herself, of course. She has a lot of other scientist buddies working on it, too. But they all believe. That one day they can wipe the Bug from the surface of the planet. That one day, even, they can reverse it for all the Ferals down on the ground.

Me, I have my doubts. Which begs the question: why I am even here in the first place? Why sign up with this lot when I just know they’re going to fail? Well, I guess sometimes you just have to pick a side. And this is the one that makes me feel the least dirty.

But still, all that blood.

I met Miranda while I was foraging in Old Monterey. She had been bagging Ferals on her own back then. Some ship captain she’d hired had bailed on her, leaving her stranded with a pack of hostile Ferals. I helped get her out.

She offered me a job. Flying her around. Keeping an eye on her while she was in the field.

At first I said no. Like I said, all that blood.

Then Gastown happened, and I saw the path the world was heading down. Miranda’s path seemed somehow better. So I changed my answer to yes.

Luckily, Miranda’s offers last longer than mine.

Back onboard the Cherub, Miranda collapses into my comfy chair. “Thank you,” she says, like she always does after one of these jobs, looking up at me from under her glasses, the way that usually makes me feel strong and brave and something of a protector and that usually defuses any anger I might be feeling. I feel the anger slip, but I grab hold of it and pull it right back to me.

“This isn’t a game.”

She raises her eyebrows. “I know that.”

“I don’t think you do.”

“I needed to get the whole sample.” She sets her jaw. “You know how this works.”

“I made my rules clear when you hired me for this job,” I say. “You hired me to keep you safe. I can’t do that when you don’t listen to me.” “I do—”

“If you lose a sample, it sets us back a bit, I’m aware. But if you get infected, this whole thing is screwed.”

“Ben—”

“So next time you listen to me or I walk.”

Silence. She bites her lip. I feel the heat flush my face. My hand is white around the barrel of the rifle.

Then she says, “We all know you prefer to fly.”

I walk over to the controls, disgusted with her. But I can’t argue with her statement. She’s right there.

The controls of the Cherub help to set me right. It’s where I belong, after all. It’s what I’m good at. I power up the engine, turning her back to Apple Pi.

It’s a stupid name, of course. But leave it up to a bunch of scientists to name something, and they’ll come up with something Latin or something cute. Apple, after the fruit of the tree of knowledge. And the one that fell on Newton’s head. Pi after the constant. And a groaner of a pun. I try not to say it too much.

Apple Pi makes me itchy, too. The place, I mean. It’s also on the ground.

My stomach yawns and I reach over for the hunk of sausage I left on the console. It’s one of the few perks of the job. It’s what attracted me to Miranda’s proposal in the first place. The boffins are better at feeding me than I am. That’s what I call Miranda’s lot—I read it in a book once and, well, it stuck. The salty, peppery meat—pigeon, I think it is—goes down easy and helps to patch up my mood.

The food thing was something of a surprise. I mean I wouldn’t have pegged scientists for being good with food. But in the kind of communes Miranda grew up in, they learned this shit. How to salt and preserve meat. How to grow vegetables and fruits without fields. I guess it all makes a kind of sense. Keeping food is really all about bacteria. There’s enough of them that know about biology that they had it sussed.

The end result is that I eat better than most, and that’s one of the things that keeps me coming back. The others… well, like I said, I’m still deciding.

I push the engines to a comfortable clip, suddenly wanting to get back to the Core. That’s what I call Apple Pi. It sits better with me. Partially because it’s the center of everything in the boffins’ activities, but also because of the apple thing. There’s not much to sink your teeth into in the core of an apple, but it does contain the seeds. Whether those seeds will actually grow anything, though, that’s always a gamble.

I may have just eaten, but I feel the need to eat more, almost as if that will justify everything. Why I put up with all this mucking about with Ferals. Why I carry their blood on my ship. Why I put up with Miranda.

Right now she’s making notations in her battered notebook. I once took a peek inside and couldn’t tell anything other than some of the scrawl was letters and some of it was numbers. She has abysmal penmanship.

Mine is much better, but then Dad drilled that into me. Insisted on me learning reading and writing. It doesn’t always come in handy here in the Sick, but it made him happy. And it helps when I come across any old books, which isn’t often but happens occasionally. And really, Ferals don’t read, so it makes me feel somewhat more human.

Yep, full speed back to the Core and I can divest myself of Miranda, at least for a little bit, and get some clear air. And food. With those and a good pistol at your side, you don’t need much else.

Well, those things and a good ship to fly. I’ve gone days without food. But the Cherub has always been there for me. Has always lifted me to safety. Has always been my home. She may not be much to look at, not with the way she’s been fixed up and jury-rigged over the years, but she’s as much family to me as my father was. She’s safety, and freedom and, dare I say, love.

That’s why, as the Core comes into sight, I realize that it will never truly feel right to me.

It will never feel like home.

The Core’s lab is proof of one of many reasons I love airships.

Let’s say that you live above the wreckage of North American civilization. Let’s say that below you, on the ground, live a horde of deadly Ferals who could pass you the Bug with just a drop of bodily fluids. But they’re little more than animals. They just sleep, eat, and fuck. Well, and hunt. Never forget that.

Let’s say that in that wreckage lie a lot of useful pieces of equipment. Lab benches, spectrometers, centrifuges, maybe even a working computer or two. Sure, most of the glass is likely to be broken up from Ferals or from earthquakes or just from time. But a Feral can’t do much to a hunk of machinery and has no cause to. No, that stuff can still be used. Only you can’t use it on the ground.

Let’s say you have an airship.… You get the idea.

’Course a whole lot of stuff like that will weigh you down, so you can’t keep it in the sky. You need a place to put it down, a place to lay it all out, hook it up. Use it. That means the ground again. And I haven’t been able to solve that particular problem. So that brings us back to Apple Pi and the lab that stretches out around me.

The place is a mess, the benches covered with towers of notebooks and papers, beakers, tubes, machines, and more. The boffins aren’t meticulous about their working environment.

What the boffins are meticulous about is their science. The experiments. The search for their cure. Each data point is marked down. Checked. Double-checked. Glass is obsessively cleaned, machines tested, to eliminate any random variables from their equations. It’s what I aspire to at times—eliminating chance from the equation, keeping things regular and right. But I know, too, that you can never get rid of chaos. And it will always dog your steps, even in the sky.

Sergei nods at me as I walk over to where he works on his project. Sergei is our fuel man. He has already developed several new biofuels, all of which work, with varying degrees of success, in the Cherub’s engines. Sergei is a big fucking reason why I stick around. I mean, he has the personality of soggy paper, but the man is a wiz with fuel. Because of course we need to fuel our ships.

And of course to fuel the ships we need to power other things. And electricity isn’t wired up the way it was in the Clean. Or so my father told me.

Sergei removes his captain’s hat, a battered old relic that Miranda tells me has nautical origins. I’ve never asked him where he got it. He wipes his damp head with his sleeve. “How did the latest batch work?”

“It worked. But it wasn’t necessarily clean. Dirtier than the last three batches, I’d say.”

He nods, thoughtful. “I’ll play with the ratios.”

“I have three jugs left,” I say. “I’ll need more soon.”

He nods again, then gets back to work, jiggling the wires to some batteries.

Power.

The boffins have used a variety of ways to get it, to power their centrifuges and electronic scales. Chemical batteries and solar panels are the most common methods. But panels are hard to repair and they tend to use most of them on the airships. A couple of old bicycles have been rigged to generate electricity through mechanical means. Cosgrove keeps talking about building a windmill, only they haven’t been able, or focused enough perhaps, to make it happen. ’Course something like that broadcasts a signal to the world around you that you’re a sitting duck, so not having one is fine by me.

Crazy Osaka is fond of telling us all how he once powered an entire lab on oranges. How he and a bunch of his colleagues stripped out an orange grove and hooked them all up to his equipment. The other boffins smile and chuckle when they hear this. Me, I almost punched the man in the face. All that food. All that energy that could have gone into human bodies, going instead into inert machinery. Well, let’s just say I found that offensive.

I bypass the lab and head to the room that I like to call the Depot. It’s really just a closet with some supplies in it, but it’s where we keep the ammo and so I think it fits.

If you ask me what the three most valuable things are in the Sick, my answer would be simple. Food. Fuel. Guns and ammo. The last helps you get the first two. Or helps you keep them. The boffins have done pretty well on the first two, but the third is something they can’t make. So it’s up to me to barter for them. We have a decent stockpile due to my efforts, but if you want my opinion, it’s never big enough.

I grab some more bullets for my dad’s revolver. It’s not always easy to find ammunition for the gun, but then again a lot of people out there seem to prefer 9mm when it comes to pistols, so that helps. I grab some more rifle ammo, too.

As I’m closing the door, I run into Clay. Or, to be more accurate, he runs into me.

“More ammo?” he says.

I flash him a humorless smile. “That’s what happens when you shoot a gun. You need to replace the bullets. Want me to show you?”

He looks at what I’m carrying. “Some would say maybe you’re a little trigger-happy.”

I grit my teeth. Step forward. “Well this ‘some’ would have to be particularly fucking naive. I’ve been hired to protect you people. Sometimes that involves shooting down the Feral about to bite your throat out.”

I’m somewhat impressed when he stands his ground. But that only makes me want to hit him all the more.

“You’re right,” he says. “Your breed is necessary for the time being. But there will come a time when you won’t be. When we find the cure, what will you do then?”

I laugh. “Go away, Clay. I’m tired of looking at you.”

Clay shrugs in a way that’s entitled and snide. “Be seeing you,” he says.

I head for the Cherub wanting nothing more than to be aboard my ship, in the air where I belong. As I’m all too often reminded, the ground is full of ugliness.

Clay joined the group only a few months ago, another scientist moth attracted to the flame of the Cure. He’s into the same things Miranda is—virology, cell biology, biochemistry. They have similar backgrounds, the children of scientists. And Clay is a believer. He holds on to the idea of a cure the same way a preacher holds on to God. Only, as he’d no doubt tell you in that sanctimonious drone of his, he’s a rational man. A man of Science. Thing is, he still believes in a fairy tale.

I rummage in the Cherub’s storeroom and come up with a bottle of moonshine that some of the boffins distilled for some celebration. Louis Pasteur’s birthday or something. I take a swig. It’s harsh and it burns as it goes down, but it’s warming and I can feel the alcohol spreading out in my system, helping to blot out the anger and frustration.

What the hell am I doing here?

It’s a question I’ve been asking myself ever since accepting Miranda’s offer.

Then I think of Gastown and the way it was overrun, and I think having something to look after, something to protect, can help save a man. The Core has clean water, clean food, and fuel. And they make enough for me to barter for ammo. My needs are met, and all I have to do in return is risk my life down on the ground from time to time, risking exposure to the Bug.

Fuck.

I take another swig of the moonshine and settle down against the console.

We are all Life’s bitches, until Death steals us away.

Falling Sky © Rajan Khanna, 2014