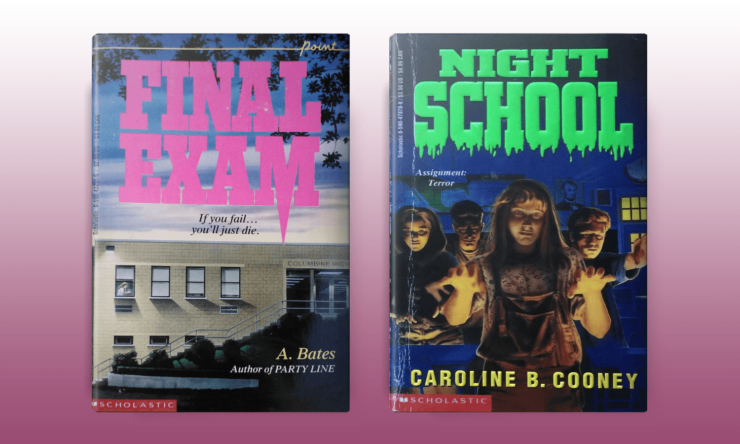

Often in ‘90s teen horror, school serves as a backdrop or a distraction, with characters drowsing their way through the school day until they can head to cheerleading practice to find out if a supernatural disaster has taken out another one of their squad-mates, or grumbling about having to shoehorn homework assignments in around trying to not get murdered. But sometimes school itself is the source of the horror, which is the case in A. Bates’ Final Exam (1990) and Caroline B. Cooney’s Night School (1995). The threat could be realistic, supernatural, or some combination of the two, but whichever it is, it makes it challenging to get to graduation alive.

Final Exam and Night School present readers with two very different high school horrors: in Final Exam, someone is sabotaging Kelly as she takes the final tests of her senior year and the driving mystery is who’s doing this and why, while in Night School, a quartet of students find themselves seduced and manipulated by a supernatural power. However, in both of these novels, a central component of negotiating the horror is these teens deciding who they are, what they value, how far they’ll go to protect the people they love, and what they’re willing to sacrifice.

In Final Exam, Kelly is on the cusp of graduation, ready to be done with high school and begin her formal training as an auto mechanic, which is her true passion. She loves fixing cars and is really good at it, completely undeterred when people suggest that this isn’t really a proper profession for a girl. In a refreshing dismissal of traditional gender roles, this doesn’t become a major point of contention or debate in Final Exam: a few people frown upon her chosen profession but Kelly doesn’t care. She encounters sexism when people doubt her skills and ability but she ignores them, gets on with the repair at hand, and proves them wrong. She’s a mechanic, she’s great at it, and it makes her happy. What else do we need to know?

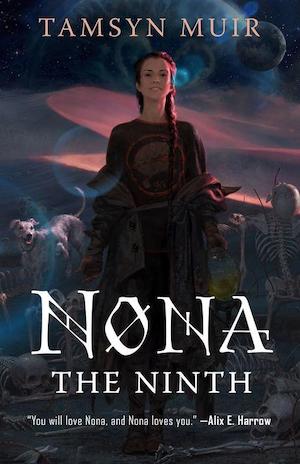

Buy the Book

Nona the Ninth

Kelly’s best friend Talia, Talia’s boyfriend Jeff, Kelly’s ex-boyfriend Danny, and Tad, the boy who’s currently trying to woo Kelly, are all getting ready to graduate as well and tensions are running high during finals week. Jeff’s admission to Dartmouth (his father’s alma mater) is conditional on his final grades, Kelly has tremendous test anxiety and just wants to get through and move on with the rest of her life, and Tad’s family has incredibly high expectations for his academic and athletic success in college. The teachers aren’t particularly supportive and the seniors are left to muddle through the stress and at-times debilitating anxiety of surviving this last week of school on their own.

In the novel’s opening pages, Kelly finds a mysterious book of “Winners” on a trip to the main office, which is filled with credos like “I am a winner. Winners win” and “Losers are going nowhere. Where are you going?” (5), which are apparently supposed to inspire and motivate but are almost nonsensically simplistic. Despite the fact that this book holds no details that would identify or incriminate its owner, there are a series of brief chapters told from this “winner’s” point of view, as they stalk Kelly, convinced that she saw them when they were stealing a copy of the English final from the main office and could rat them out, jeopardizing their promising future. (Kelly saw nothing, has no idea the English final had been stolen until she’s accused of stealing it herself, and wouldn’t tattle even if she had, but the “winner” doesn’t know or care about any of these things). Kelly’s life gets increasingly complicated as finals week goes on: someone eggs her vintage Thunderbird, destroys her Spanish test, sets a fire in her bedroom garbage can, fills her locker with spray cheese, swaps out her chemistry book to sabotage her potential success on the open-book exam, and mutilates her signature derby hat. Kelly doesn’t end her high school career in a blaze of glory. Instead, she leaves school with all of her fellow seniors at the end of the day on Friday, knowing that she has to come back on her own on Monday to retake several tests, still under pressure while the rest of her friends are celebrating the end of finals week and their high school careers.

While some of the pranks Kelly endures are more dangerous than others, familial expectations and relationships end up being the most terrifying part of Final Exam. Kelly’s younger sister Susan is jealous of Kelly because of her close relationship with their father, who abandoned the family but still bonds with Kelly over cars, including calling to offer her a summer job with him fixing cars on the racing circuit. Tad’s father screams obnoxiously from the stands during the baseball game, critiquing and berating his son. Jeff’s entire sense of self-worth rests on getting into the college his father wants him to go to, and Talia is terrified to tell anyone that she didn’t get into the colleges she applied to, uncertain of what will come next for her with that particular door now closed. Kelly broke up with Danny because he’s violent, after he punched her locker and broke one of her car windows, though this doesn’t stop her from still being attracted to him and doesn’t stop her sister Susan from going out with Danny to make Kelly jealous. When Tad, the most popular and accomplished guy in school, takes a sudden interest in Kelly, her first concern is that he’s just interested in being with her for the novelty of dating someone so far below his socioeconomic station and someone who isn’t a cheerleader. These are complicated interpersonal dynamics that Kelly is ill-prepared to navigate, repeatedly stating that cars are a whole lot easier to understand than people, retreating to her garage to work on a tricky mechanical problem as a way of avoiding these high-stress emotional crises.

Susan confesses to some of the pranks pulled on Kelly, including the egged car and the cheese-whizzed locker, but it turns out Jeff is the mysterious “winner.” He tricks Kelly into going with him to the middle of nowhere, where his car has broken down, and then attempts to murder her to get his book back and to make sure his secret’s safe. As he prepares to push both Kelly and her car over the edge of the cliff, he reverts to a childlike state, begging for his father’s approval as he says “She’s heavy, Dad. But I won’t drop her … I can do it. I’ll keep going forever and never quit. I’m a winner, Dad. You’ll see. I’ll be the best. Just for you” (185) and later hysterically imploring as he asks “Are you proud now? Are you proud of me?” (188). Jeff jumps off the cliff and though he is injured, he survives. His psychotic break even ends up being positively framed in the novel’s final pages, as the psychiatrist notes that “now no one can fool themselves into thinking his problem isn’t so bad” (198). It can’t be minimized or ignored anymore, and Jeff will get the support and help he needs (though whether his father will change is another story— one that remains untold).

The teens in Cooney’s Night School face similar interpersonal challenges. Mariah is not quite sure how to cope with or support her severely depressed brother Bevin, Autumn struggles with her identity being subsumed as part of the mean girl clique of Julie-Brooke-Autumn-Danielle, Ned is relentlessly bullied, and Andrew is a popular guy who is afraid people will see through his facade. When a mysterious flier appears on the bulletin board at school for an unnamed night class, all four sign up: Andrew out of curiosity, Mariah because she has a crush on Andrew, Autumn because she wants to do something on her own away from Julie-Brooke-Danielle, and Ned because he’s looking for friends. These four may also have been targeted by the supernatural malevolent power that teaches this night class (whose enrollment closes once they have signed up), but their own anxieties and personal weaknesses are integral in getting them to sign their names on the sheet and walk through the door.

When the four arrive at night class, they find that their instructor is amorphous and disembodied, a shadowy form with a hypnotic and seductive voice that tells them they will learn “to control the dark” (49). Autumn initially thinks this is some sort of self-help metaphor, but the teacher means this literally, as the four teens are given the power to control darkness and shadows, for the singular purpose of terrifying individual targets, identified as “Scare Choices” (SCs for short). The first SC they try their powers on is a substitute teacher named Mr. Phillips, who is staying late in the library to do some grading. The collective students are an invisible force, turning out the lights, moving objects, making scary noises, and generally terrorizing the SC (who they stop referring to or thinking of by his name as soon as they begin attacking him, distancing themselves from the consequences of their actions and dehumanizing their target) until he breaks down and flees. They feel safe in their anonymity and in their collective participation, with each making excuses and absolving themselves of any wrongdoing, as they reassure themselves that they didn’t actually hurt him, that they were only going along with the group, and that they don’t bear any individual, personal responsibility, highlighting a mob mentality that sets in surprisingly quickly. Each negotiates the question of whether there is evil in inaction and to what degree they are responsible for the harm that comes to others, though the instructor reassures them that it is “never our fault … We just start things. It isn’t our problem if it goes on and on, its own little ripple effect” (153, emphasis original).

These four teens are bonded together by their shared experience, but simultaneously isolated from one another as they grapple with their own sense of culpability and complacency in what happened, and worry about whether they can trust the other three. They live in fear that someone will find out what they’ve done (the instructor clandestinely recorded their attack on Mr. Phillips, showing them all at their very worst). The power they have gained is tainted and corrosive, particularly when the instructor tells them that their next assignment is for each of the students to choose a new SC. Autumn picks her friend Julie, while Mariah does everything she can to make sure no one singles out her brother Bevin (she fails at this). Each of the four are constantly suspicious of one another, fearful that their fellow night class students will turn on and terrorize them.

Bevin and Julie are peripheral characters, though Cooney provides readers with extended passages from each of their points of view. Though Julie is the queen bee of the mean girls and mercilessly cruel to most of her peers, she is also terrified of the dark, keeping nightlights aglow in her room, hallway, and bathroom. Julie is desperate to change and has her sights set on going far away for college, where she would “never again know anybody from this high school where she had been so mean, so often. She would sling away this bullying she did, and make it history. In her college world … [she would] always be nice and beloved of everybody” (122). But when she wakes up every morning and goes to school, her best intentions melt away and “every day, she got meaner, and better at being mean” (122). Cooney’s sections from Bevin’s point of view are heartbreaking in his naked need to be seen, to have his suffering recognized and addressed. When Mariah comes home to find that Bevin has destroyed their shared rec room, her first impulse is to clean up the mess. Bevin looks on, thinking that “It never failed to shock [him] how little people noticed of his, Bevin’s, existence. And here he had gone ballistic, breaking every representation of their lives, as a prelude, or maybe a blockade, to destroying his actual life, and Mariah was vacuuming. Dusting. Hiding it, so their parents would never see” (120). Bevin starts skipping school, returning home to descend into a nearly catatonic depressive state, but no one notices his absence, calls his parents, or checks in on him. He finds himself at a crossroads, “down to only two choices now: death or disappearance” (132). Though Julie hurts people on a daily basis, no one stands up to her, and while Bevin suffers on the brink of suicide, those who love him come up short when he really needs them, either remaining oblivious to his pain or unable to effectively respond, frozen in debilitating silence.

The night class’s salvation comes from the most unlikely of directions and the most coincidental of connections, through the combined power of Julie and Bevin. While the night class’s members have identified Julie and Bevin as SCs, these two find strength in one another when Bevin, contemplating suicide, calls Julie’s number looking for his sister, even though Mariah and Julie have never been friends. In her desperation to help Bevin and stop him from killing himself, Julie is able to break the spell of the night class, storming right through the illusions they have set in place to terrorize her as she runs to save Bevin. Julie finds Bevin in his kitchen and though she is the unlikeliest of allies, she is the first to directly articulate Bevin’s depression and suicidal planning. Julie “thought: I can’t use the word, even though I’m here and that’s why I came and that’s why I had to drive so fast. Then she thought: I have to use the word. I have to admit it. We’re all going to have to admit it. ‘Would you have committed suicide, Bevin?’” (171-2). Bevin says he doesn’t know, succumbing to confusion and despair, and he and Julie have a heartfelt conversation that may be one of the most transparent and authentic discussions of teen mental illness, depression, and suicide in the genre. There’s no quick fix and no magical resolution, but there’s a glimmer of hope, a strengthening support system, and the possibility for Bevin to move forward, no longer defined by an overwhelming and fatalistic hopelessness.

As with Final Exam, there are a lot of loose ends and unresolved conflicts at the end of Night School, beyond the crisis point of Bevin’s mental health. The four night class students are able to break the spell of their instructor when they realize that “you get a choice … Pick on people or don’t pick on people. Be kind or be cruel. Watch it happen or stop it from happening. You have a choice” (183). While these four are dropping their night class, though, there are countless classes who have come before them and who pose a constant threat, as each of these students must live with the possibility—and perhaps even likelihood—that they will be chosen as another, more advanced class’s SC and be powerless to stop it. While they collectively make the choice to quit the night class, strong in the support of their peers, when Andrew is left alone to make the decision for himself, he is drawn once more into the darkness, reminding the reader that everyone is eventually on their own, must individually decide for themselves have the courage of their convictions.

The horrors that shape and drive Final Exam and Night School are very different, ranging from the realistic to the supernatural. However, at the heart of each novel is the question of who these teens want to be and what matters to them. Jeff is driven to violence in Final Exam because he is willing to sacrifice anything and anyone to gain his father’s approval, while jealousy and pain motivate Susan to play unkind pranks on her sister, driving a wedge further into their already fractured relationship. In Night School, Mariah loves Bevin and wants to protect him, but she falls short, not seeing the warning signs and not there when he needs her the most, though she promises to do better in the novel’s final pages. Julie’s change of heart could be fleeting or limited to Bevin alone; after all, she has found and lost her resolve to be more kind so many times before. Andrew decides the power offered by his night class instructor is worth whatever he has to give up to keep it. Their formal exams may be over, but it is how they do on these real-life tests that determines who they are and how they’ll move forward.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.