Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

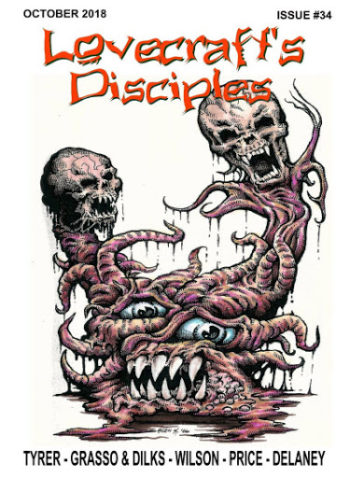

This week, we’re reading Robert M. Price’s “The Shining Trapezohedron,” first published in the 2018 issue of John B. Ford and Steve Lines’s Lovecraft’s Disciples. Spoilers ahead.

“Men once called me Pharaoh. Now behold: I am about to do a new thing.”

Reverend Enoch Bowen, pastor of the First Free Will Baptist Church in Providence, has won a lottery to accompany a Miskatonic University archaeological expedition to Egypt. Though not a professional academic, Bowen is a “well-informed amateur in scholarly questions, especially as regards biblical history”; the prospect of walking the same “eternal sands” as Moses and Pharaoh thrills him core-deep.

The night after his win, he has a strange and vivid dream. Clad in a linen tunic, he lies on a smooth-tiled floor in a chamber he’s never seen in waking life. Bracketed torches emit greenish light. A form appears before him, features strangely obscured as if by too much shadow or too much light. He can’t tell which. The angel (as he identifies the figure) tells him he, Enoch Bowen, has been chosen by God to discover a “great treasure of a spiritual nature… a Grail of knowledge for which the world was starved.” Bowen rises in the morning “with an unshakable sense of adventurous expectancy.”

He takes a tearful farewell of his congregation; then it’s off to Arkham to meet his fellow explorers. Though the archaeologists treat him affably enough, he senses their condescension towards the party’s designated cleric. Bowen’s not offended and privately vows to do all he can to assist in their search for the hidden tomb of Pharaoh Nephren-Ka. Nephren-Ka was a heretic whose successors sought to efface his historical memory; hence controversy persists over whether this “Black Pharaoh” was even real.

Buy the Book

Flyaway

On the transatlantic voyage, Bowen studies his Bible and meditates on Joseph, whose envious brothers sold him into Egyptian slavery but who ended up the Pharaoh’s Grand Vizier. He fancies some relevance to his own situation in Joseph’s story, as well as in the story of pre-Flood patriarch Enoch the undying, whom God favored to walk with Him across the heavens.

Once in the field, the archaeologists realize tracking down Nephren-Ka will be a daunting task. Sixtyish Bowen tries to help with the excavations but is soon exhausted. Dr. Farrington suggests he undertake another service—a contact in Abyssinia has written Farrington about Coptic manuscripts of possible Gnostic provenance; perhaps Bowen can do a preliminary assessment of their legitimacy. Bowen eagerly accepts the assignment.

A brief camel ride and Nile voyage bring Bowen and his Egyptian guide to a Monophysite monastery dug entirely into the earth. Bowen and the monastery’s agent quickly come to terms on the manuscripts, but overnight his guide disappears. No problem: The agent, Abu Serif, can guide Bowen back, detouring along the way to an ancient site unknown to Westerners. Bowen accepts the offer, excited at the prospect of scouting a virgin dig for the Miskatonic expedition.

They venture into the desert on camelback. Bowen sickens with nausea and mental fuzziness, losing track of how many days they travel. One morning Abu Serif tells him they’ve reached the unknown site: the tomb of the Black Pharaoh, Nephren-Ka! He also admits he knew all along who Bowen was, and why Bowen has been summoned to this place.

Summoned? Bowen in particular, not the archaeologists? And by whom?

Ask him yourself, says Abu Serif. He shows Bowen the open mouth of a tomb, but declines to enter. Bowen ventures through a long, dim-lit passage to a stone-flagged chamber he recognizes as the scene of his pre-expedition dream. He feels both dread and relief that the dream’s meaning must now become clear. Nor has he long to wait. A “three-dimensional silhouette of absolute blackness and radiating cold” appears (as it says) “In the Name of Mighty Nyarlatophis.”

The figure claims to be the “Trismegistus,” once a Pharaoh. It is about to “make all things new,” and Bowen, “blessed above [its] Million Favored Ones,” will deliver its tidings unto shepherdless mankind. Bowen has only to gaze into this here asymmetrically faceted stone, glowing softly with blood-red radiance, to “know as you are known.”

Bowen, prostrated before the figure, obeys. He sees fleeting images. Among them are visions of former selves: Xaltotun wakes, ringed in his sarcophagus by conspirators who’ve revived him using the magic gem called the Heart of Ahriman. The scene shifts to the citadel of Beled-el-Djinn, City of Devils, where the wizard Xuthltan is being tortured by a king who covets his prophetic gem, the Fire of Asshurbanipal. Xuthltan summons a tentacled devil to dispatch his torturers. Scene shift to Belshazzar of Babylon receiving a blood-red gem dredged from drowned ruins in the Persian Gulf, where it had lain on the breast of a mummified king. Cyrus takes the gem from Belshazzar, and on it passes, from king to king, thief to thief, even unto Apollonius of Tyana, who gazes into the Philosopher’s Stone and lifts his head filled with new secrets. At last, as from above, Bowen watches Joseph Smith hunch over a glowing Seer Stone that reveals to him “the unknown histories of vanished peoples.”

Meanwhile back at the expedition digs, the archaeologists search for Bowen. This search fails as miserably as their search for Nephren-Ka. They’re about to give up and return to the States when Bowen walks into camp. The old cleric’s much changed, sun-blackened, clad in shredded red robes that might have been looted from a tomb. Two jackals attend him, “affectionately licking his outstretched hands,” and as one man the “dusky laborers” bow to Bowen.

The Americans don’t know what to say, or to think.

What’s Cyclopean: The citadel called Beled-el-Djinn.

The Degenerate Dutch: Dusky Egyptians all bow to Nyarlathotep. N. is also apparently the source of Mormon cosmology.

Mythos Making: Bowen gets to Egypt via a Miskatonic University expedition, where he encounters a shining trapezohedron (“Haunter of the Dark”) in the tomb of Nephren-Ka (“Haunter” and also “The Outsider”). The trapezohedron proceeds to show him the collected works of Robert E. Howard.

Libronomicon: Bowen reads the stories of Joseph as well as his namesake Enoch to prepare him for his trip to Egypt. Spoiler: he is not prepared.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Everyone gets through this story sane, though not necessarily in possession of their original identities.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Part of me thinks this would have been the perfect week to cover riffs on “Masque of the Red Death.” Honestly, though, holed up in my decadent fortified castle mysteriously-crowded-with-people-working-from-home manor house, it’s a relief to spend some time thinking about straightforward dangers like getting mesmerized by a font of overwhelming knowledge.

Nyarlathotep is probably laughing Its thousand faces off.

Anyway, I’m an easy sell on the weird and pulpy this week. Price’s kinda-sequel to “Haunter of the Dark” delivers the basics: classic location, normal guy vulnerable to having his mind blown, mind-blowing eldritchness, and a couple of cool images. I spent half an hour not thinking about current events, which is definitely my idea of a good time right now.

“Haunter of the Dark” earned a few riffs in the early Mythos, probably because it was itself a response to a Bloch story, part of an ongoing exchange of affectionate fictional murders. It’s not exactly forgotten in current works (the Cult of Starry Wisdom has a Westeros chapter), but often buried amid the greater cornucopia of Deep Ones and Mi-Go. I’m a big fan of Deep Ones and Mi-Go, but think the trapezohedron is woefully underused. (Possibly obvious since I’ve used it myself, as a major Mi-Go-and-Deep-One-related plot point in Deep Roots.) So I’m happy to see it here, playing a starring role.

N’s well-placed biblical quote is a perfect encapsulation of the trapezohedron’s promise: “You will know as you are known.” Lovecraft’s prototype palantir offers a terrifyingly tempting exchange: a window into alien perspectives, in exchange for giving Nyarlathotep direct access to your brain and/or body. Even without giving an elder god your neurological password, the gift of perfect empathy is itself double-edged. You might get a peek at how elder things see the world, or you might—as here—get a brief history of evil wizards.

The trapezohedron also provides endless opportunities for shoutouts to fellow writers of the weird. Price pulls most of his revelations from Robert Howard: Xaltotun is a Conan villain, “The Fire of Asshurbanipal” is a short story with Mythosian connections, and so on. People slake evil thirsts with the blood of screaming virgins. And then we get Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism, definitely not a Howard creation.

The rest of the story provides the minimum scaffolding needed to get Bowen in place to receive his jackals. (Pet jackals—also a tempting trade for elder god service! I suddenly want a Birds of Prey crossover, jackals versus hyenas.) The Miskatonic expedition in particular seems underfunded compared to their usual efforts. They have no idea where to dig and give up almost as soon as they start; this is the same school that uncovered the aeons-old Arctic stronghold of the elder things, and that almost managed to penetrate the Yithian Archives in the middle of the Australian desert. Bowen’s presence, part of an equally half-assed attempt to repair the university’s town/gown relationship, makes me suspect N’s hand tweaking the whole situation long before the jackals arrive.

Anne’s Commentary

On his personal website, Robert M. Price assures readers that none of his fiction is “veiled autobiography.” I’ll take his word for it as far as him acquiring the Shining Trapezohedron is concerned. If Price possessed the ST, this world would be a different place, though I’m not prepared to speculate on what those differences might be. That writ, the author and protagonist Bowen do have things in common. Bowen is pastor of a Baptist church. Price was briefly pastor of the First Baptist Church of Montclair, New Jersey. Both are Biblical scholars, with Bowen modestly described as “a well-informed amateur” while Price holds advanced degrees in theology and has taught religious studies at the college level. Price has also published an impressive body of nonfiction concerning his reassessment of his faith, which he describes as finding “traditional Christianity did not have either the historical credentials or the intellectual cogency its defenders claimed for it.”

Pre-Egypt Bowen seemingly enjoys unshaken faith, despite realizing it won’t do to tell his scientist teammates that God will guide them to Nephren-Ka’s tomb—you see, Bowen’s been vouchsafed a dream of their success, via a kinda vague angel, but what else could the shadowy-bright figure be? Nor will they reap mere academic and financial rewards, for Bowen’s destined to bring forth a “Grail of knowledge” for which the world’s been starved!

Bowen commits no sin of “prideful self-importance,” either. He really is a Chosen One. So what if he has to lose his original religion? All his meditations over the Bible just leave him puzzled and frustrated, which implies something’s lacking either in Bowen’s comprehension or in the Word itself! Bowen dares not suppose the latter, not until he meets the One who’s really Chosen him, and that ain’t no angel.

Or is it the only true angel, Soul and Messenger of Azathoth the All-Source? You know, Nyarlathotep (or, here, Nyarlatophis.) What a clever (and irony-loving) entity Nyar is, too, courting Bowen into his new faith with the language of his old one. Without Bowen’s tidings, men are but shepherdless sheep! When Bowen looks into the Shining Trapezohedron, he will “know as [he is] known,” wording straight out of 1 Corinthians.

How could Bowen not trust this 3-D silhouette of blackness and radiating cold? How could he not look?

When Lovecraft’s Robert Blake looks into the ST, he sees cosmic vistas, right up to “an infinite gulf of darkness, where… cloudy patterns of force seemed to superimpose order on chaos and hold forth a key to all the paradoxes and arcana of the worlds we know.” Bowen, in contrast, does the sort of trip down incarnations past we saw in Long’s “Hounds of Tindalos.” Maybe Bowen’s a bit self-important after all?

It’s fun how two past Stone-Bearers come straight out of Robert E. Howard, another of Price’s favorite authors. Xaltotun was an ancient wizard resurrected by the Heart of Ahriman to become Conan’s fearsome antagonist. Wizard Xuthltan wrested a problematic magic gem from its demon-keeper in “The Fire of Asshurbanipal.” Xuthltan, not coincidentally I wager, is the original name of the witchy village featured in “The Black Stone.” I’m not sure how the historical figures Belshazzar and Cyrus were involved with magic gems, or Apollonius of Tyana either. Joseph Smith, founder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, did own “seer stones,” supposed potent in the folk magic of nineteenth-century America. The pertinent one was an egg-sized chocolate-brown stone Smith found while excavating a well. It later figures in his translation of the Book of Mormon. Like the Shining Trapezohedron, Smith’s seer stone manifested its spiritual light and power only in darkness. Reportedly Smith would put the stone in the bottom of a hat which he then held over his face, thus achieving the requisite obscurity for revelation.

Does Price imply, via Bowen’s vision of past stone-users, that all stones were the Shining Trapezohedron? Or, like Nyarlathotep, does the ST have many “avatars,” forms, inmineralizations, while remaining in the Many, One?

The second makes magical-theological sense to me.

Enoch Bowen gets scant mention in “Haunter of the Dark,” appearing chiefly in the scribbled notes of Haunter-fried newspaperman Edwin Lillibridge. Here Price plays the classic literary game of taking another’s minor character and fleshing him out, spinning forestory out of backstory. Lovecraft makes Starry Wisdom founder Bowen a professor whose archaeological work and occult studies are well known. Professors, doctors, scientists were Lovecraft’s default characters. Men of faith, no, unless their faith centered in some dark cult. With his rich background in religious and theological studies, it’s not surprising Price makes Bowen a clergyman, or that he hints Bowen has slow-simmering doubts, the potential for spiritual crisis—or revolution. The title of Bowen’s last sermon sounds confessional—he’ll be “Seeking God in the Sands of Egypt,” and why? Because he hasn’t found him in the streets of Providence?

And is it fortunate or tragic that Bowen does find a new god? The palely deferential, frail preacher returns from the desert proudly erect, with an excellent tan, vintage red robes and a pair of adoring jackals. The Egyptians bow to him, because they know what’s what, while the academics (faintly ridiculous in khakis and pith helmets) haven’t a clue.

Team Fortunate Fall here, but then I’ve always been a Nyarlathotep fangirl.

Next week, speaking of the Mi-Go, we’ll read Christopher Golden and James A Moore’s “In Their Presence,” from the Gods of H.P. Lovecraft anthology.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is now available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.