Having grown up during the Cold War, I was introduced in high school to all the classic twentieth century dystopian novels (Brave New World, 1984, Fahrenheit 451). We were taught that the surveillance state was the norm of our totalitarian enemies, or a threat to our own future if we let down our guard. Coming of age during the rebellious Sixties and entering college at the explosive end of the decade, I became politically engaged and concerned about the many ways that we all face manipulation, surveillance, and control—whether by governmental agencies (the bugaboos of the time were the FBI and CIA) or through advertising, political propaganda, and mass media. I have been a science fiction fan for as long as I could read, and at the dawn of the computer era, when the room-filling mainframe predominated, the genre worried about HAL and Colossus, machines that sleeplessly watched and gathered power over us. One of my favorite movies of the late Sixties was The President’s Analyst, a satirical spy thriller in which the universal watchman (spoiler) is the phone company.

In this century, popular culture takes the surveillance state for granted, sometimes in the form of awful warnings, sometimes as a fact of life we all have to accept or even exploit, ideally for good purposes. A clear example is the recent television show Person of Interest, which presumes a master computer, created for the War on Terror, that can continually monitor the entire population. The heroes endeavor to use this power for good ends in opposition to other human agents who simply seek mass control. This, of course, is the quandary we confront in the age of social networks and smart phones that communicate our wants, needs, and locations to everyone, voluntarily or not—an age of drones and pocket cameras that can potentially record all of our activities. As with other forms of technology, however, these new tools of interactive surveillance can be a benefit or a hazard, can either serve the goals of higher powers or expand individual choice. What is not in doubt is that they will transform our understanding of privacy, and maybe even make it obsolete.

I had the opportunity, indeed the necessity, of probing this subject in more detail as author David Brin’s co-editor for the new anthology Chasing Shadows. Through science fiction stories and a few essays, this anthology explores a range of possibilities inherent in our increasingly transparent society, as do the books below.

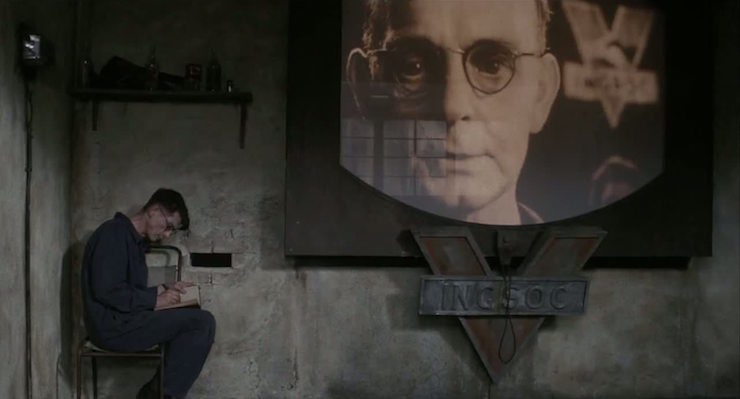

1984 by George Orwell (1949)

1984 reflects the author’s concerns about the dictatorships of his time, although it was also inspired by his activity at BBC radio during World War II, rewriting the news to make it conform to the propaganda needs of wartime. Orwell extrapolated the growing influence of electronic media—radio, movies, and TV—and their potential for misuse by power, from the broadcasting of propaganda rallies to televisions that can watch us back. As a classic awful warning tale, it established the parameters for surviving (or not, in this case) the surveillance state.

1984 reflects the author’s concerns about the dictatorships of his time, although it was also inspired by his activity at BBC radio during World War II, rewriting the news to make it conform to the propaganda needs of wartime. Orwell extrapolated the growing influence of electronic media—radio, movies, and TV—and their potential for misuse by power, from the broadcasting of propaganda rallies to televisions that can watch us back. As a classic awful warning tale, it established the parameters for surviving (or not, in this case) the surveillance state.

Shockwave Rider by John Brunner (1975)

Brunner anticipates cyberpunk in his portrayal of a character who can weave his way through an increasingly computerized society. Trained as a genius to serve the technocracy, the protagonist hides from, and indeed within, the system by periodically changing identities through his reprogramming of the database. Brunner mingles utopian possibilities with dystopian ones, showing how committed individuals can use the power of technology to thwart abuses of same.

Brunner anticipates cyberpunk in his portrayal of a character who can weave his way through an increasingly computerized society. Trained as a genius to serve the technocracy, the protagonist hides from, and indeed within, the system by periodically changing identities through his reprogramming of the database. Brunner mingles utopian possibilities with dystopian ones, showing how committed individuals can use the power of technology to thwart abuses of same.

Little Brother by Cory Doctorow (2008)

Little Brother is considered an adolescent novel, although it has been challenged as too mature and too anti-authority for young readers, especially by authority figures. A response to the contemporary War on Terror, it portrays a group of tech-savvy teens in a near future who get scooped up in the wake of a terrorist attack on San Francisco. They respond effectively with cyber-attacks on the Department of Homeland Security. As the title hints, the book offers an alternative to the pessimistic assumptions of Orwell’s classic.

Little Brother is considered an adolescent novel, although it has been challenged as too mature and too anti-authority for young readers, especially by authority figures. A response to the contemporary War on Terror, it portrays a group of tech-savvy teens in a near future who get scooped up in the wake of a terrorist attack on San Francisco. They respond effectively with cyber-attacks on the Department of Homeland Security. As the title hints, the book offers an alternative to the pessimistic assumptions of Orwell’s classic.

The Circle by Dave Eggers (2013)

A polemical fable featuring one Mae Holland, a young woman who seems to land the perfect job at the high tech company The Circle. Its latest gadget is the SeeChange, a wearable camera that guarantees everyone perfect “transparency,” consistent with the company slogans: Secrets are Lies; Sharing is Caring; Privacy is Theft. Mae is very much with the program, to the point of betraying all other characters who express concern about the potentially dystopian consequences of this technology.

A polemical fable featuring one Mae Holland, a young woman who seems to land the perfect job at the high tech company The Circle. Its latest gadget is the SeeChange, a wearable camera that guarantees everyone perfect “transparency,” consistent with the company slogans: Secrets are Lies; Sharing is Caring; Privacy is Theft. Mae is very much with the program, to the point of betraying all other characters who express concern about the potentially dystopian consequences of this technology.

The Transparent Society by David Brin (1998)

The one non-fiction book on this list, The Transparent Society was written at the dawn of the internet era—before the proliferation of drones and camera phones—and is prescient is laying out the challenges for the twenty-first century. Brin counters the fears of the surveillance dystopia with advocacy of “sousveillance,” that is, turning the technology of transparency back on big institutions, private and public, as a guarantor of democratic civilization.

The one non-fiction book on this list, The Transparent Society was written at the dawn of the internet era—before the proliferation of drones and camera phones—and is prescient is laying out the challenges for the twenty-first century. Brin counters the fears of the surveillance dystopia with advocacy of “sousveillance,” that is, turning the technology of transparency back on big institutions, private and public, as a guarantor of democratic civilization.

Top image: Nineteen Eighty-four (1984)

Stephen W. Potts is in the Department of Literature at the University of California, San Diego, where for more than thirty years he has taught science fiction, fantasy, and other topics in popular culture. Over that period he has published numerous books, articles, essays, and even some science fiction. He is the co-editor, along with David Brin, of the new anthology Chasing Shadows.

Stephen W. Potts is in the Department of Literature at the University of California, San Diego, where for more than thirty years he has taught science fiction, fantasy, and other topics in popular culture. Over that period he has published numerous books, articles, essays, and even some science fiction. He is the co-editor, along with David Brin, of the new anthology Chasing Shadows.