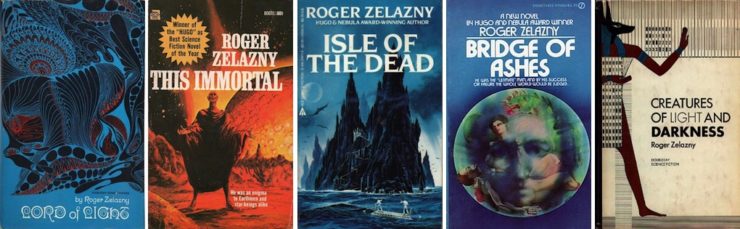

You always get asked, “When did you know you wanted to be a writer?” And, of course, there’s no answer, or a thousand answers that are all equally valid. But I usually say, “In high school, when I read Zelazny’s Lord of Light.”

You see, until then, I had never known you could do that. I never knew you could make someone feel all those different things at the same time, with all of that intensity, just by how you used 26 characters and a few punctuation marks. What was it? Well, everything: Sam and Yama were the most compelling characters I’d come across; it was the first time I’d ever stopped reading to just admire a sentence; it gave me the feeling (which proved correct) that there were layers I wouldn’t get without a few rereadings; and, above all, it was when I became of what could be done with voice—how much could be done with just the way the author addressed the reader. I remember putting that book down and thinking, “If I could make someone feel like this, how cool would that be?” Then I started reading it again. And then I went and grabbed everything else of his I could find.

One of the first ones that fell into my eager hands was This Immortal, the novelization of “…And Call Me Conrad.” And there is a moment in that book. (The rest of this paragraph is a spoiler, so skip it if you want.) There are hints from the very beginning that our hero may be a kallikantzaros, a Greek demon. We are introduced to the folklore: the sawing away of the tree of the world, other bits and pieces. One of them is the riddle of the kallikantzaros: “Feathers or lead?” You have to guess, and if you guess wrong, it kills you, and the answer is whatever the kallikantzaros wants it to be. All of this, because Zelazny was a master of voice, is conveyed in a slightly ironic, “Isn’t it an amusing story?” sort of way—up until our hero finds himself tied to stake in a radioactive pit with his enemy about to slice him open to see how far his intestines will stretch, at which point our hero says, “Feathers or lead?”

My heart dropped into my stomach, and started pounding, and what I felt can only be described as awe. I said to myself, “If I could write a scene that would do that to someone, how cool would that be?”

One could argue (hat tip to Teresa Nielsen Hayden) that the central challenge of all fiction is solving the problem of exposition—that is, what information to convey to the reader, and how best to do so. That argument aside, certainly exposition is one of the biggest challenges in science fiction and fantasy, because we need to explain, in essence, the difference between the world the reader is reading about and world the reader is living in, and we need to do it in such a way that said reader doesn’t get bored or confused or irritated and go back to that real world.

There are many ways to handle this problem, and many ways to screw up if you don’t do it well, but I’ve never seen anything like what Zelazny did in Isle of the Dead. He throws concepts at you, and bits of business, and characters, and purely on the strength of the narrator’s voice, carries you to a point about a third of the way into the book, where he stops cold and fills you in on everything you’ve been missing in what ought to be a boring monologue, but somehow isn’t. At the end of this, you are so caught up in the plot (that you didn’t even know was going on a few pages ago) that you can’t put the book down. I don’t know how he did it. I just shook my head and said, “If I could manage something like that, how cool would that be?”

Bridge of Ashes is a fun book, though not, by Roger’s standards, one of the best. But—read the prologue. Disjointed first person scenes, interesting, because just the way Zelazny writes makes you want to keep reading—but unconnected. Several of them. Wait, is that something that all have in common? I’m not sure. What? A longer scene, that explains a few things, but leaves the big question unanswered: What is going on? I’m intrigued, I keep reading. Another short scene, and somehow it comes together. “Oh … I get it now.” Suddenly I’m proud of myself for having solved the puzzle. And the next sentence I read is, “At last I begin to understand,” and I find myself holding the book, staring, going, “How did he do that? Man, if I could get so far into the reader’s head to be able to pull off something like that, how cool would that be?”

I had a strange relationship with Creatures of Light and Darkness. I didn’t much care for it the first time I read it. I read it again a few years later, probably about 1976 during a periodical total reread, and decided that, weird and disjointed as it was, there was some Cool Stuff there. I mean, the Steel General has to be one of the most remarkable characters in fiction, and then there’s Madrak’s Possibly Proper Death Litany, or the “agnostic’s prayer” as it has come to be called. The third time I read it I was blown away: the use of language, poetry imbedded in prose, the over-all sweep of the narrative finally hit. And the fourth time it had me in tears. This keeps happening, because every time I read it, I find layers and resonances and nuances I’d missed before. I remember thinking, “If I could write a book that kept getting better every time someone read it, how cool would that be?”

Pretty cool, I think. Pretty cool.

Steven Brust is the author of 26 novels, including the Vlad Taltos series and the Khaavran romances. His latest, The Skill of Our Hands (co-written with Skyler White), is available from Tor Books.

Steven Brust is the author of 26 novels, including the Vlad Taltos series and the Khaavran romances. His latest, The Skill of Our Hands (co-written with Skyler White), is available from Tor Books.

I need to read, or reread, pretty much all of those. I came to Zelazny in high school primarily via Amber, but the public library had a number of his other titles, including Doorways in the Sand, which I thought was great. I kind of bulled my way through Creatures of Light and Darkness. Bounced hard off of Lord of Light; years later, I read an excerpt (one of its component novellas?) in a Gardner Dozois anthology, and that convinced me that I should go back and try again, which was a wise choice on my part.

And I love those covers, particularly Lord and Creatures.

I’ve read only Lord of Light and the Amber books by Zelazny but they are ones I reread often. I should definitely check out these other books!

Also keep writing more scenes set in Valabar’s in your Vlad Taltos books and you’ll definitely achieve the goal of it being better every time its read. (I live for those food scenes)

I’ve loved everything Zelazny since I hit Lord of Light.

It’s still the one book I pimp on all of my friends. If you read no other book, read this one.

Lovely piece, Steve. Roger’s work taught me that an author doesn’t need to have one voice, one theme, one set of endlessly re-worked characters, but that this isn’t a reason to NEVER return to familiar settings, familiar characters, and show that there’s something new to discover.

He wrote with such variety it was a pure delight to see what he’d try next.

I wish he was still around to surprise us.

I will second @1’s mention of Doorways in the Sand. I would also include Zelazny’s great short fiction, such as “A Rose for Ecclesiastes” and “Home is the Hangman”.

Love everything Zelazny wrote but the one I love the most is A Night in the Lonesome October. One of the last books he wrote, a standalone with very Lovecroftian overtones and very funny. SLIGHT SPOILER (very slight since it’s usually spoiled on the description): it’s told from the perspective of Jack the Ripper’s pet dog. It’s often overlooked but well worth checking out. Another very good but overlooked novel is Roadmarks, also a standalone. They make me wish he had returned to the world of either of these books. And believe me, I’m not knocking the Amber series, but I also love, love, love his short story collection The Doors of his Face, The Lamps of his Mouth and other stories. There’s not a dud in there, and the title story alone is worth the price.

For me, it was Doors of His Face, Lamps of His Mouth and especially, Rose for Ecclesiastes. I made a close friend in high school when we discovered that we had both written just written poems inspired by Rose.

The first Zelazny I ever read was Creatures of Light and Darkness. Since then, every time I pick up one of his works, I hope to replicate that experience. I’ve liked most of those works, and I loved Lord of Light, but with Creatures it was love at first page, and I’ve never yet found anything to compare.

Oh my god – I recall reading these in my teens (a long time ago). They are life changing! Thanks for the reminder.

I cut my SF teeth on Creatures of Light and Darkness, and hold Lord of Light as one of those Really Important Books in SF. Isle of the Dead has always struck me as a very personal book, and I frequently revisit it. Cheers, Steven.

Started with Amber and that led to the hard stuff. Lord of Light is one of my all time favorite books; not only does Zelazny have a way with words but he has a way of making even the most outlandish characters seem real.

Hence our cat. Mahasamcatman. “They called her Mahasamcatman and said she was a cat. She preferred to go by Sam. She never claimed to be a cat; then again, she never claimed not to be one…”

Huh. So that’s where Jack Campbell got the “feathers or lead” bit Duellos alluded to in the Lost Fleet books.

Perhaps the one item I love most about the SF community is its reluctance to allow its foundational works – and foundational masters – gather dust in a forgotten corner; thus avoiding the ignominy of Mark Twain’s definition of a classic book.

And who better than you, Steven Brust, to write this appreciation of Roger Zelazny and (some of) his oeuvre? Your mastery of language and setting and scene parallels, even rivals, Zelazny’s. His and your intelligence suffuses your works so an informed reader can enjoy the books at a different level. So I believe. I am not alone.

I just placed This Immortal and Isle of the Dark on my iPad and to the top of its spindle. Peeked at This Immortal (I read it L O N G ago) and see immediately just how cagily brilliant Zelazny was.

As are you. Freedom & Necessity, To Reign in Hell, The Sun, the Moon, and the Stars, and Agyar – each without peer. I reread them frequently. (“I feel the need to write something more before I go on my way, something that can go on top of this pile of papers, and the last shall be first, as someone or other said in a different context.”)

I wonder who will write the appreciation of you and your work, as you just did for Roger Zelazny. You deserve it. And success, of course. Thank you for all.

His novella, “For a breath I tarry”, invariably makes me tear up on re-reads (of which there have been many). Densely allusive–structured akin to the book of Job and Marlowe’s Faust, bits of the eponymous Housman poem throughout, it’s a joy to read. I’ll probably discover more layers with closer reads. And there are the unanswered questions–who, for example, is the strangely self-aware tempter “Mordel”?

His characteristic dry humour also holds great appeal for me, though he was an egregious punster. “The fit hit the Shan” in Lord of Light, the moons Flopsus, Mopsus and Katontallus in Isle of the Dead…

The great novel-masquerading-as-a-game, Planescape: Torment, was supposedly influenced by the Amber novels. The way Corwin’s character evolves through the series is, I think, similar to the central question of that game, “what can change the nature of a man?”

There’s an amazing youtube video of RZ speaking at a convention in the late ’80s; I think I spotted Mr. Brust in the audience! He reads from a hilarious short about an intelligent word processor who “improves” novels, RZ’s sense of humour was evidently often self-deprecating. I only regret that I never had the opportunity to meet him (not that I would’ve had anything intelligent to say as a callow teen). Or the great Jack Vance, who lived much closer to me but passed away just a few days after I met someone who knew him and offered an introduction. Alas!

If I recall correctly, in the preface to “Shadowjack” from the 6-volume collected short stories, Roger notes that Jack from “Jack of Shadows” was named for Jack Vance!

I kind of backed into Z’s works, started with Dilvish the Damned and then The Last R Master. (Sci-fi book club sale titles back in the day.) One of those very rare writers who don’t seem to have any misses.

Lord of Light was a very big deal for me too when I was a kid. I really liked Yama. Also Taraka the Rakshasa and Rild/Sugata, truly enlightened by a false Buddha. I’d put Creatures of Light and Darkness second and Nine Princes in Amber third.

With great objective rigor I can force myself to admit there might have been the odd Zelazny book that was not in fact the greatest of all time, but his style worked so well for me that it really didn’t matter. I just loved every word.

As brilliant as his novels were, his short stuff was the best. So much impact folded into so few words. And his narrative voice was among the best–no one before or since could do snark like him.

I also really dug ‘Shadow Jack’ when I read it as a young teenager. I was really into the Bakshi movie ‘Wizards’, and the technology vs. magic paradigm of Shadow Jack resonated with that.

A Rose for Ecclesiastes was the first of his I read. It blew me away.

I always felt he was talking directly to me. Not just because of his mastery of first person. It was more like he knew me and we were friends. To me, I guess we were. Amber set the hook, the shorts reeled me in. I also enjoyed the Changeling/Madwand books.

The Vlad tales have the same sort of feeling with the first person. Love when this is done well.

Yeah, I also have a soft spot for a lot of his more … minor? works — Jack of Shadows and Dilvish the Damned, e.g.

Ah, my! Thank you for reminding me of these, I’m going to be seeing more of the public library than I.have been. And finally reach into the middle of my To Read pile for Hawk!

That was a pleasure to read. I didn’t even know about Bridge Of Ashes. Now I have to go find it.

I love Lord Of Light, but I would like an edition without that truly dreadful pun about the Shan. Can it be arranged?

The entire 10 books Amber series is one of my all time favorites! I reread it often.

1. Lord of Light is outstanding.

2. Jack of Shadows is oft overlooked, I think.

3. A Night in the Lonesome October: one of its last lines of dialogue “Any port in a storm” …. still makes me smile when I re-read it, which I do about once a year.

And Mr. Brust…. when is Vlad once again going to walk the pages? It has been 2.5 years…. WAY too long.

Surprised no one mentioned, Eye of the Cat…loved nearly everything he wrote . Discovered him in the school library of my dreary 70,,s Catholic boarding school in a troubled N Ireland. He saved from something, even if I am not sure what it was. Boredom perhaps. But he was such a skilled writer, and truly opened my mind to more exotic pursuits Have just started ‘re reading Amber……

Lord of Light was my first. Then Creatures of Light and Darkness, followed by the Amber books and Call me Legion. Then the others.

They inspired me to wrote. I had never sat back to examine the meta of writing, but Zelazny got me thinking about the structure, the sentences, the words. What was the intended effect?

He introduced me to Whitman, House an, and other writers. I found I loved poetry and started writing my own.

Then I wrote Zelazny. All I got back was a short note on a postcard, but it had several enigmas planted within. And I was inspired further. The world became dimmer when he left us.

Thank you, Mr. Brust for this assessment. You bring back memories, not only of the stories he told but of the man himself. Roger wrote with boldness, daring to take his readers out of the reading of the book to admire something: a phrase, an image, a piece of dialogue.

In 1977, while sitting in the cafeteria of my fiancee’s workplace, I read Doorways in the Sand almost in its entirety. It was, I believe, his only fully comedic novel. I laughed out loud and got instant glares from others in the cafeteria. An alien disguised as a donkey addresses Cassidy, explaining why he was late in finding him: he had to make a substitution. “What substitution?” Cassidy asks. The alien replies, “The real donkey is tied up out back.”

Roger DARED the reader to break away from the reading to laugh or to cry or to shout out loud. He was that good.

I too, had to read and re-read Creatures many times. Then it just made sense all the way around. I have enjoyed the Amber series of novels, but my favourite bock of his has always been Eye of Cat.

Zelazny is my favorite author. We was brilliant, clever, knowledgable. His were the first books I ever read in first person, at least as a semi-adult. I’m sure I read the Amber books first, and I loved them. “A white bird of my desire came and landed upon my right shoulder…” Something like that, with the fallibility of memory and all. I believe I have read Zelazny’s entire canon of work, with the exception of the second Amber series. I tried it and it didnt’ hold, probably I was too much in love with the first series to accept the second.

No one else has mentioned it yet, so I will. My favorite Zelazny book is Today We Choose Faces. The protagonist is a deceased mafia boss, whose descendent revives him in order to send him to assassinate an enemy fortified in a base on the moon. While he’s on this mission, there’s is a nuclear holocaust on Earth. And then it gets stranger. Read it if you can find it.

I feel sad in these times, when I am browsing in a book store and discover that they have no titles by Zelazny; an unforgivable oversight.

Yes, not seeing his stuff in sci fi sections is a scandal.

I’ve just reread most of his major novels and short stories,as good as ever.

Top 5 in no particular order: Nine Princes in Amber,Roadmarks,This Immortal, Lord of Light,Isle of the Dead.

1. Lord of Light. In Grade 8, on a boring family trip to granparents. The richness of that writing was such a contrast to the experience of the trip!

2. Jack of Shadows

3. Roadmarks

4. Eye of Cat

5. 9 Princes of Amber