Some readers may be familiar with the mission of the Down Under Fan Fund; for those who are not, allow me to quote from the official site:

DUFF, the Down Under Fan Fund, was created by John Foyster in 1970 as a means of increasing the face-to-face communication between science fiction fans in Australia and New Zealand, and North America. It was based on an earlier fan fund called TAFF which did the same for fans in Europe and North America. Other fan funds have spun off from these two, all in the name of promoting a better understanding of worldwide fandom.

As it happens, this year I am one of four candidates for DUFF. More details can be found via previous DUFF winner Paul Weimer’s tweet.

Of course, the tradition of sending people very far away for various laudable reasons is an old one. Unsurprisingly, this is reflected through the lens of science fiction. Various SF protagonists have been sent quite astonishing distances; sometimes they are even permitted to return home. Here are five examples.

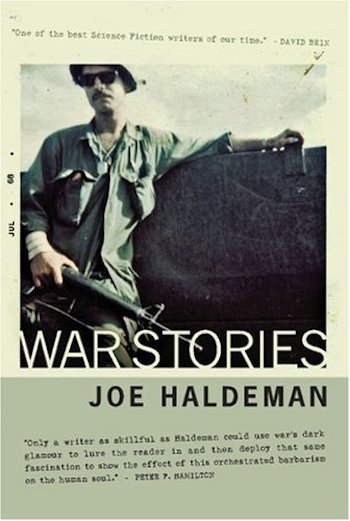

In Joe Haldeman’s 1970 story “Time Piece,”1 humanity is spared the grim spectre of peace thanks to two fortuitous developments: transgalactic travel and the discovery of the alien Snails, against whom humanity can unite in glorious struggle! True, the “relativistic discontinuities” that facilitate interstellar travel appear to be limited to the speed of light, forcing soldiers like Naranja, Sykes, and Spiegel to fast-forward through history. While this means human society is almost as alien to them as Snail society, at least this grand perspective permits Naranja to appreciate how thoroughly the Snails are out-competing humanity.

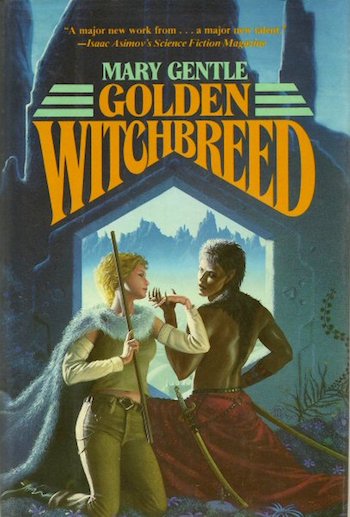

Relativity is not an issue in Mary Gentle’s 1983 Golden Witchbreed. Faster-than-light drives mean the galaxy is traversable in just ninety days. The problem for the Dominion of Earth diplomatic service is scale. Thousands upon thousands of systems have life2; many of them are home to indigenous civilizations. In short—many, many planets, too few available diplomats.

The Dominion of Earth dispatches extremely junior diplomat Lynne de Lisle Christie to distant Orthe. She replaces a functionary who died under mysterious circumstances. Christie is under the impression that Orthe is a backward world that has yet to match Earth’s heights. She is very wrong. This misapprehension will cost her dearly.

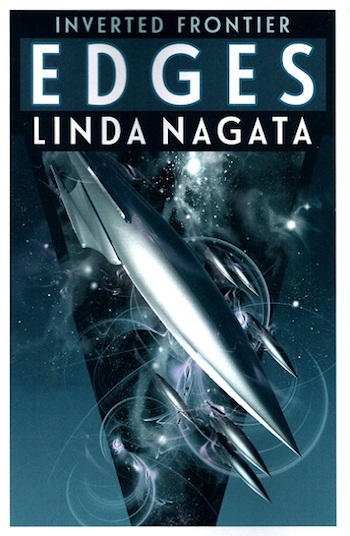

Linda Nagata’s 2019 Edges begins at Deception Well, out at the edge of human settlement. Deception Well is isolated by vast distances, relativity, and some all-too-functional alien war relics. Enough information trickles to that distant outpost that the human settlers eventually realize that the stellar systems closest to the Solar System, systems long settled and once prosperous, have gone silent. What could have gone wrong with such well-established advanced civilizations? The only reasonable course of action3 is for Urban and a company of adventurers to make the long, slow trip to the old worlds to see what precisely has gone wrong… Because that’s going to end well.

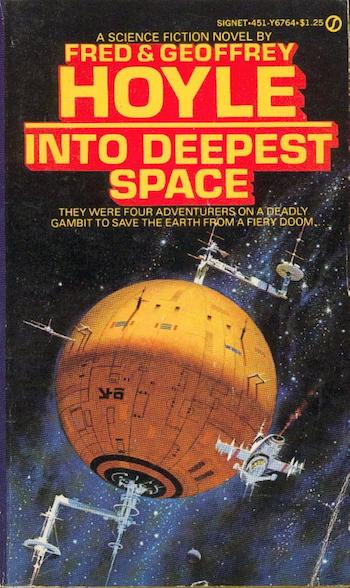

Fred and Geoffrey Hoyle’s 1974 Into Deepest Space begins where their earlier (1969) novel Rockets in Ursa Major left off. A near-future Earth is still coming to grips with the revelation that humans have interstellar cousins who have so annoyed other, more advanced civilizations that whenever said aliens encounter a human-occupied world, they commit prudential genocide. Go Team Human!

Dick Warboys sets off on a sublight expedition into deepest space to better understand our alien enemies. The effort does not go entirely according to plan4, but the explorers do get a grand tour of the Milky Way and regions beyond, and they do survive to return, after some delay, to a much-changed Earth in possession of a very personal grasp of just how far down the intergalactic pecking order humans really are.

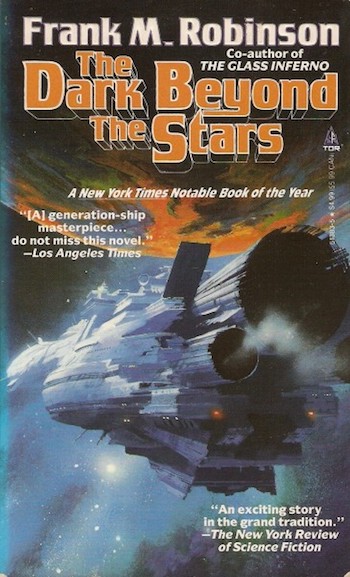

Frank M. Robinson’s 1991 The Dark Beyond the Stars doesn’t make use of the common SF tropes of FTL travel at relativistic speeds. His protagonists plod along at sublight speeds. The Astron and its crew have been searching for life-bearing worlds for two thousand years, an effort that has thus far failed to pay off. Captained by an immortal who could give Ahab lessons in obsession, the Astron has reached the edge of the Dark, a vast gulf in space. The captain sees no option but to continue—a hundred generations will live and die crossing the Dark, but to turn back now would be to betray all previous generations who lived and died searching in vain for a second Earth. Only crewman Sparrow seems to have qualms about attempting to traverse the Dark in a generation ship already showing its age, and amnesiac Sparrow is but a very junior crewman.

Of course, there have been many, many science fiction books featuring epic interstellar journeys, most of which were not mentioned in this five-book list (which by its very nature must list just five books). Feel free to mention noteworthy examples in comments.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assAlsted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He was a finalist for the 2019 Best Fan Writer Hugo Award, is one of four candidates for the 2020 Down Under Fan Fund, and is surprisingly flammable.

[1]I bet you thought I was going to mention his The Forever War.

[2]I am being vague here to conceal this unfortunate howler: “Maybe a hundred million stars in this galaxy. Maybe a hundred thousand planets capable of supporting life we’d recognize as life.” That should be hundred billion and if we keep the proportions consistent, one hundred million life-bearing worlds. Or to put it a different way, about one life-bearing planet per hundred humans.

[3]“Hide in terror from a galaxy full of alien killbots” is also a correct answer, but not the one they pick.

[4]This seems like a good place to hide a warning that the thin plot and thread-bare characterization of the novel are matched only by shockingly terrible science. This is odd, given that one of the authors was a professional astronomer. Granted, a professional astronomer working under the significant disadvantage of being Fred Hoyle.