Some recent online conversations started me thinking about the women speculative authors of yore. Not the recent yore, when I was a teen or at least a kid, but days even more of yore than that: the 1950s and earlier1.

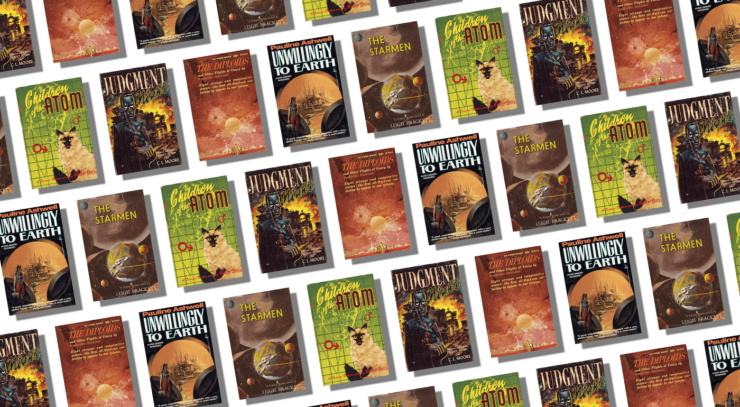

Wondering what I mean? Here are five works of speculative fiction from an era so long ago that even I did not exist. No doubt a few of the following works are known to you. The few that are not might be worth reading.

The Diploids and Other Flights of Fancy by Katherine MacLean (1962)

While the collection itself is of 1960s vintage, the contents of this splendid MacLean collection almost all date from the early 1950s, the lone exception being from 1949. MacLean was a skillful author who could shape her stories to fit diverse markets. However, most of the stories in Diploids were published in two of the three flagship magazines of the period, Astounding (now Analog) and Galaxy. Galaxy was more open to SF that was more humanistic, less tech-focused, while Astounding paid better.

My favorites in this volume are “The Snowball Effect,” which features a social experiment successful far beyond its creators’ contingency plans2, and “Pictures Don’t Lie,” in which seeing really should have been believing. Also of note, “Incommunicado,” a tale of human-machine rapport that was wildly praised in its era.

I am a bit disappointed that MacLean, a Cordwainer Smith Award recipient, was never further honored as a SFWA Grandmaster. SFWA did name her Special Author Emeritus in 2003. Who knows? Perhaps they will consider MacLean for the Infinity Award.

Children of the Atom by Wilmar H. Shiras (1953)

A 1973 nuclear power plant mishap killed many unlucky staff members. Some survived, despite radiation exposure, and went on to have children… mutant children.

On meeting one mutant youth, child psychologist Peter Welles is quick to deduce that there must be others. America can be an unwelcoming place to unusual people. Rather than leave the mutant children to the vagaries of mob justice, Welles establishes what one might call a school for gifted youngsters. However, Welles’ attempts to ensure peaceful relations between man and mutant will not play out as he envisioned.

Modern readers may recognize in Children of the Atom a possible inspiration for Marvel Comics’ X-Men. The differences outweigh the similarities. Shiras’ mutants are geniuses, but lack flashy physics-defying superpowers. More importantly, Shiras takes her plot in an entirely different direction from the conflict-heavy comics. The result is closer to Zenna Henderson than Stan Lee or Jack Kirby.

The Starmen by Leigh Brackett (1952)

Michael Trehearne feels himself perpetually out of step with the rest of the world. He travels to Brittany in search of family roots and an answer to his malaise. To his surprise, he discovers that his origins may be far more exotic than he ever could have imagined. Michael may be a hybrid human, the illicit offspring of a Varddan, one of the starmen of Llyrdis3. He certainly demonstrates Varddan immunity to the effects of superluminal travel. Whatever Michael’s true origins, he provokes a crisis amongst the starmen. The easiest way to deal with disruptive elements is, of course, to kill them… but Michael is hard to kill.

Michael is an issue because he potentially threatens the Varddan Council’s monopoly on star flight. The Council claims that they must protect their monopoly because every other flavor of human is so xenophobic that breaking the monopoly would lead to interstellar war. It’s mere coincidence that their efforts have an unintended side effect: empowering and enriching the Council.

Judgment Night by C.L. Moore (1943)

Armed with the wisdom of the Ancients of Ericon, dynasty after dynasty dominated the galaxy, then fell to their own folly. Imperial heir Juille is determined to preserve her family’s empire. Egide of the H’vani believes it is his people’s time to rule. Juille believes prophecy ensures her certain victory… but then, so did every previous dynasty.

Readers might expect that Juille will fall for Egide as soon as she sees his impressive jawline. Moore didn’t write that sort of heroine. Juille never loses track of her goal. She is not nearly as good at listening to the oracles’ unambiguous warnings, but then, what would happen to the plot if she took time to consider those?

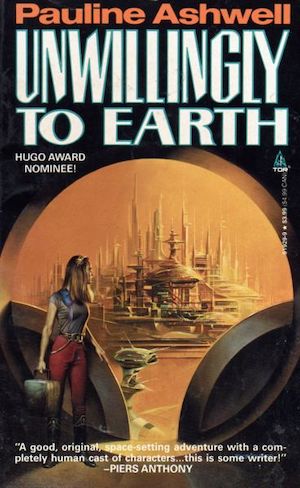

“Unwillingly to School” by Pauline Ashwell (1958)

Frontier girl Lizzie Lee wields lies and half-truths to achieve her ends. Her talents are sufficient to wrap the rough-and-ready pioneers of Excenus 23 around her finger. Will Lizzie Lee succeed in fast-talking her way off her birth world and into a Terran university program for cultural engineering?

Lizzie is nearly as good as she thinks she is. There were moments where Lizzie reminded me of Mattie Ross’ horse-trading in Portis’ True Grit. As it happens, social manipulation is a regulated trade in this universe; Lizzie explains, in her eccentric dialect, just why that is.

Of course, women have written science fiction and fantasy since the field began. This is only a small sample; I’ve had to overlook many interesting works. Feel free to mention your pre-1961 favorites in comments below.

- This unfortunately excludes Ursula Le Guin, whose prose SF did not appear until just after I was born. I will also neglect pre-Gernsbackian authors like Margaret Cavendish and Mary Shelley because while works like The Blazing World and Frankenstein would be classified as SF if published now, they predate SF in its modern sense. I will also regretfully omit Judith Merril’s Year’s Best S-F anthologies, because as delightful as they are, most of the works she chose were works by men.

- Because they didn’t bother with contingency plans. Or, for that matter, research ethics.

- It’s best not to wonder how all the worlds of the galaxy got their own humans in a story that seems to be set in the 1950s. Exceptionally parallel evolution, I suppose. Also, it’s odd that nobody of significance on Earth seems to have noticed off-world traders.

(tap tap tap) is this on?

It is. But I don’t think I’ve read any of those, or any works (that I knew were )by women previous to 1965. Except for Shelly.

Not even Andre Norton? Although I don’t know when it became general knowledge she was a woman. As far as I remember, that was known by the time I started reading SF.

The only one of hers I’ve read that I recall was the one with Earth abandoned to uplifted animals because the virus that did the uplifting was fatal to humans. And then humans returned. Read it once in the late 70’s. Didn’t become aware until later that she was a woman.

Well, the good news is there’s a lot of entertaining stuff you have not read yet [1].

1: None of which is Norton’s Quag Keep.

I believe Lizzie Lee’s original struggle was to not go off-planet and go to school, but instead to remain on-planet, where she had control.

Andre Norton’s Sargasso of Space and Plague Ship, the first two Solar Queen books, were published in 1955 ans=d 1956. Catseye, my possible favorite, was published in 1961.

Those “Solar Queen” books were by Andrew North. :-)

If I remember right, a character with specific local ambitions is pivotal in Anne McCaffrey’s “Weyr Search”. And come to think, the heroine of “The Stainless Steel Rat” has some goals that aren’t met. But there I’m definitely straying from exemplary female achievement in prose.

“Andrew North” was one of Andre Norton’s pseudonyms. :-) (Andre Norton also being a pseudonym, la!)

It wasn’t a pseudonym until later. :-)

It was always a pseudonym – it wasn’t known it was one until later.

I could only think of Jirel of Joiry and Lud in the Mist as pre 1960’s SFF I have read by a female author – but I have read the Solar Queen books.

I love the original novella In Hiding by Shiras. Really nicely done tale of a seemingly normal kid whose teacher thinks something is off and brings in a psychiatrist – who pokes around and eventually discovers a kid who really needs help. I’m sure I have read Children of the Atom in the past, and not recently, but I have returned multiple time to this well crafted origin story.

There’s always Herland by Charlotte Perkins Gilman from around 1915.

Margaret St. Clair wrote a lot of good stories in the period under discussion; I’ve read at least one collection of hers.

I have long wanted to read Leigh Brackett, knowing her only through her early involvement in The Empire Strikes Back screenplay, and to my shame have never made the time to do so. Maybe I’ll start with The Starmen. Thanks for an interesting article and good recommendations!

Memoirs of a Spacewoman by Naomi Mitchison published in 1962, might be just too recent , but Pilgrimage: The Book of the People (1961) by Zenna Henderson fits the bill, because the stories were written in the 50s like MacLean

Zenna Henderson needs far more love than she gets!

I was in mid-High School, and visited a college bookstore. In it, I found a copy of Pilgrimage I remember how Lea’s Plea struck me as a place I was in, and had been in:

“Everything is nothing,” Lea gasped, grabbing for the comfort of a well worn groove. “It’s nothing but gray chalk writing gray words on a gray sky in a high wind. There’s nothing! There’s nothing!”

I can actually say that Zenna Henderson saved my life. She is one of four Christian authors I truly respect (the others being C. S. Lewis, Madeleine L’Engle, and Andrew Greeley).

I was going to suggest Rosel George Brown’s Galactic Sybil Sue Blue but that turns out to be from 1966. If we’re counting collaborations, Judith Merril wrote Gunner Cade with Cyril Kornbluth in 1952, using a pseudonym.

That cutoff date made this game a lot more difficult…

Not that hard, surely? Dune Roller by Julian May, Step IV by Rosel George Brown, The Agony of the Leaves by Evelyn E. Smith (not that EE Smith), The Wines of Earth by Margaret St. Clair, That Only a Mother by Judith Merril, Mr. Sakrison’s Halt by Mildred Clingerman, and Pelt by Carol Emshwiller.

A bit of love for <i>Judgement Night</i>! The ending in particular feels so much like a post-bomb story that I bought the original magazine to make sure it had actually been published in 1943 and not the mid-1950s.

It’s not a perfect work (nothing from that era is), but Moore did a fantastic job of creating futures that feel like they haven’t occurred yet, and it engages with colonialism and empire in ways I wouldn’t have expected a work of that era to do.