In this monthly series reviewing classic science fiction books, Alan Brown will look at the front lines and frontiers of science fiction; books about soldiers and spacers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

We now have the technology to build autonomous weapon systems: weapons that decide what and where to attack. Military organizations already use a variety of piloted drones, designed to operate in the air and on land and sea. Machines can now beat humans in quiz shows and at games of skill. Homing weapons, once fired, exercise rudimentary autonomy. Over fifty years ago, science fiction writer Keith Laumer created the Bolos, autonomous and self-aware tanks of massive proportions. And in doing so, he explored the ethics, and the pros and cons, of these weapons. This was not a dry exploration—Mr. Laumer was never one for a dull tale. In this post, the second in our recurring series of reviews of classic science fiction focused on the front lines and frontiers of science fiction, I’ll be reviewing a book that collects many of the Bolo stories, The Compleat Bolo.

There is an old Latin saying: Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? It translates as “Who watches the watchmen?” or “Who guards the guards?” When we create military power and raise armies, there need to be checks and balances, controls that ensure the military serves the best interests of society at large. In the best possible world, virtues such as loyalty and honor themselves serve as checks on this power, but when we add machines into the equation, a whole new world of problems and issues are created.

Like many authors who began their careers in the 1960s and before, many of Mr. Laumer’s best remembered works are short stories. Back in those days, authors could earn as much or more writing short fiction for magazines as they could writing novels. Laumer (1925-1993), a former U.S. Air Force officer and Foreign Service officer, was best known for two series of stories: the tales of Retief, a hard-charging diplomat whose adventures were often comical, and those of the Bolos, gigantic tanks produced over centuries, with increasing power, intelligence and autonomy. His stories were always action-packed, paced like a hail of machine gun bullets, and often replete with wish fulfillment. His heroes were larger than life, and Laumer was never one for half measures. His comedy was broad, his action bold, and he wore his sentimentality on his sleeve. Pushing his themes to the limit, however, meant they were going to create a strong impression—I immediately recognized a number of the stories in this anthology, even though it had been decades since I had first read them.

The Compleat Bolo is an anthology of short stories and a short novel; the stories are included in roughly chronological order, based on the model number of the Bolo represented in the story. The Bolos start out rooted in reality, products of General Motors in Detroit, and at first simply seem like more capable versions of tanks with increasingly automated support systems. Over time, we see them gain in power, and in autonomy. As they become more powerful, their capabilities become increasingly fanciful, and the Bolos become more allegory than a plausible extrapolation of technological trends. Laumer uses these stories to warn of the danger of vesting the power of life and death in machines, but also makes it clear that humans themselves are not good stewards of this power. Laumer’s stories have no laws of robotic behavior that we might compare with Asimov’s “Three Laws of Robotics.” Since those laws focus on not harming humans, they would be wildly inappropriate for programming a weapon of war. Instead, the machines are programmed to respect classic military virtues: honor, camaraderie, bravery, and dedication.

Because of the chronological order, in the first two stories the tanks are supporting characters—which is rather jarring in a book dedicated to Bolos. The first story, “The Night of the Trolls,” is a typical Laumer story: The protagonist wakes from suspended animation in an abandoned base, to find that civilization has collapsed during the decades he has been sleeping. A local warlord needs his help to control two “trolls”: Bolo fighting machines that could tip the balance of power. He has his own ideas about the right course of action, however, diving headlong into action and battling through overwhelming odds and grievous injuries to win. In this story, the early Bolos can perform only the most rudimentary of tasks without an operator onboard.

The second installment, “Courier,” features a Bolo from about the time of “The Night of Trolls,” but is instead set in the far future. It is a story of the diplomat Retief, a man of action who foils an alien invasion as much with his fists and his pistol as his negotiating skills. Along the way, he outwits an ancient Bolo combat machine that allies of the aliens attempt to use against him. It is a good example of a Retief story, in all of its comical glory, but almost irrelevant to this collection. (Whenever I read the Retief stories, I always wonder how many times in his own diplomatic career Laumer must have been tempted to punch someone instead of talking to them. He certainly uses the character to do things that no diplomat could do in reality.)

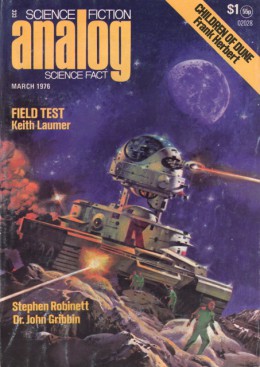

“Field Test” is the first story in the collection that deals with an autonomous Bolo, this time in a Cold War setting. The western Concordiat is at war with the eastern People’s Republic. The military leadership has mixed feelings about deploying the Bolo, but do so out of desperation. Things go better than they expect, but only because the Bolo acts in a way that they completely did not foresee, in a triumph of military virtues over common sense. Bolos are in every aspect frightening monsters—but in this story, as in others, Laumer humanizes the machine, and draws the reader into caring for, and sympathizing with, the Bolo.

“The Last Command” is perhaps the best of all the Bolo stories, one that has been burned into my brain ever since I first read it in my teens. In it, a construction project awakens a battle-damaged and highly radioactive Bolo that was deactivated and buried deep underground; the Bolo is disoriented, and decides that a nearby city is an enemy fortress. Only an elderly military retiree, eager to do his duty one last time, stands between the Bolo and its objective. At the same time the story recognizes the danger of giving the power over life and death to a machine, it also demonstrates that courage can win the day. I remember being moved by this story as a youngster, and found it even more moving now that I am an old military retiree myself.

“A Relic of War” is a neatly constructed tale where we find a retired Bolo sitting on a town green on a faraway planet—it’s a familiar image, reminding the reader of the old tanks and artillery pieces that sit in front of town halls and VFW posts across the country. The townspeople enjoy talking to old “Bobby,” as he retains a feeble shadow of his intelligence. A government man who comes to disable the Bolo is met with resistance; the townspeople just don’t see any danger from this aged and amiable machine. But then an unexpected threat arises, and by the end of the tale, everyone’s viewpoint, including that of the reader, has changed. This is another strong tale, which gets right to the heart of the overarching theme of Laumer’s Bolo stories.

In “Combat Unit,” a story told entirely—and quite cleverly—from the Bolo’s viewpoint, alien scientists try to experiment on a disabled Bolo, only to find that they have awakened a threat that will destroy the balance of power that has persisted between themselves and the human race. Bolos may be damaged, even nearly destroyed, but they are never, ever off duty. Like many of Laumer’s best stories, this one is compact, compelling, and to the point.

“Rogue Bolo, Book One” is a short novel. It was written later in Laumer’s life, after he suffered from an illness that had a profound effect on his writing. It tells a coherent tale, but in an episodic, epistolary format: a string of letters, notes, transcripts and messages—at times, it feels more like a detailed outline than a finished work. It abandons the serious tone of the other Bolo stories and takes the form of a satirical farce, as a huge new Bolo, nicknamed Caesar and built on a future Earth where an Empire rules, becomes the only defense between the human race and an alien race. This Bolo has powers and capabilities that are rather implausible and is nearly omnipotent. The story clearly shows the intelligence of the machine as superior to the intelligence (or lack of it) that the humans in the story display; the Bolo quickly realizes that its human masters are not to be trusted, and the tail begins to wag the dog. It is a good thing for the humans that the Bolo, despite its superiority and insubordination, remains unwaveringly loyal to the better interests of its human creators.

“Rogue Bolo, Book Two” is not really connected to “Rogue Bolo, Book One,” but is instead a short story, “Final Mission,” that appeared in the same volume as “Rogue Bolo” to bring it closer to novel length. This story repeats themes of the earlier stories, as a Bolo stored in a local museum is reactivated. Its efforts are needed to save a town from an invasion by aliens who are breaking the treaty that ended the last war. The town is inhabited by venal civil officials, an inept militia, and of course, a disrespected former military man who comes out of retirement to save the day. Once again, the humans owe their lives to an underappreciated but still dedicated machine.

The Compleat Bolo is not an anthology of uniform quality; some stories are classics, while others are merely entertaining diversions. But the idea of the Bolos, and the themes Laumer explored, are strong and compelling. When he was at his best, his stories were tight, fast-paced, thoughtful, and at the same time entertaining. He looked beyond what was possible in his day, and his speculations certainly resonate here in the present. With today’s drones, humans are still in the loop when it comes to life-and-death decisions like firing weapons, but we can easily see a future where opponents vie for control over the electromagnetic spectrum and operators drop out of the loop. There will be a great temptation for the military, used to letting machines do the fighting, to take that next step and allow the machines to operate without needing human intervention. I myself think it is unlikely that we will ever develop a machine as loyal and wise as a Bolo, so I don’t look forward to that development, but it certainly looks like we are heading in that direction.

SF books do not always age well, and often have elements that a modern reader must overlook. The Bolos were definitely a creation of the Cold War mentality, when each side competed to build bigger and more powerful weapon systems. Future warfare, if it involves autonomous machines, will more likely be fought by swarms of small and nimble networked machines, rather than gigantic behemoths like Bolos. Also, Mr. Laumer’s characters were strongly rooted in mid-20th-century America—even his towns on faraway planets feel like small towns in Middle America, and his use of slang from this era has not aged well, giving the stories a dated feel. But Mr. Laumer was not trying to create reality in his tales. I always got the impression that there was no hard-and-fast future history on his desk, like you might infer from some other authors’ work. Instead, for him, the individual story and the idea behind it were the most important things. Judged from that perspective, his writing was very successful: Once you get past the dated jargon, his tales speak to issues that we still grapple with today.

Laumer’s Bolos were a compelling concept, as demonstrated by the fact that the stories have been reprinted for decades. Laumer’s stories were always fun and entertaining, as well, so it is no surprise they are still being read. The original Bolo stories spawned a cottage industry of Bolo books written after Laumer’s death by some of the best military science fiction authors in the business, with six shared world anthologies and seven standalone novels appearing to date. Today, as our technology begins to make some of the capabilities of a Bolo possible, and we pause to consider our next steps, his speculations give us much to think about, illustrating the strengths, and more importantly the dangers, that could be posed by warfighting machines.

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for five decades, especially science fiction that deals with military matters, exploration and adventure. He is also a retired reserve officer with a background in military history and strategy.