Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

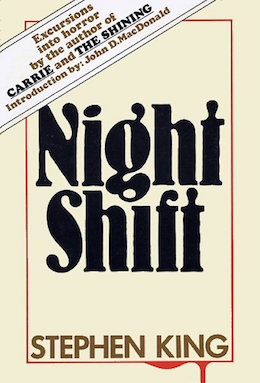

This week, we’re reading Stephen King’s “Gray Matter,” first published in the October 1973 issue of Cavalier and later collected in Night Shift. Spoilers ahead.

“Can you feature that? The kid all by himself in that apartment with his dad turning into… well, into something… an’ heating his beer and then having to listen to him—it—drinking it with awful thick slurping sounds, the way an old man eats his chowder: Can you imagine it?”

Summary

In a sleepy town near Bangor, Maine, Henry’s Nite-Owl is the only 24-hour store around. It mostly sells beer to the college students and gives old codgers like our narrator a place to “get together and talk about who’s died lately and how the world’s going to hell.” This particular evening, four codgers plus Henry have gathered to watch a nor’easter “socking drifts across [the road] that looked like the backbone on a dinosaur.”

Out of the storm comes a boy who looks like he’s just escaped that dinosaur’s maw, or stared into the mouth of the hell the world’s becoming. Timmy, Richie Grenadine’s son, is a fixture at Henry’s—since Richie got himself retired from the sawmill on worker’s comp, he’s sent the kid to pick up his nightly case of whatever beer’s cheapest. Richie always was a pig about his beer.

Timmy begs Henry to bring his father the case. Henry takes the terrified boy into the storeroom for a private talk, then returns to shepherd red-eyed Timmy upstairs to his wife and a decent feeding. He asks narrator and Bertie Connors to come along to Richie’s house, but won’t say anything about what spooked Timmy so much. Not just yet. It’d sound crazy. He’ll show them something, though: the dollar bills Richie gave his son for beer. They’re tainted with foul-smelling gray slime, like “scum on top of bad preserves.”

Henry, Bertie and narrator bundle up and head out into the storm with the beer. They travel on foot—no use trying to get a car up the hill to Richie’s apartment house in a foot of unplowed snow. The slow going gives Henry time to show his companions the .45-caliber pistol he’s packing, and to explain why he’s afraid it may be necessary.

Timmy’s sure it was the beer—that one bad can among all the hundreds his dad chugged night after night. He remembered how his dad said it was the worst thing he ever tasted. The can smelled like something had died in it, and there’d been some gray slime on the rim. Narrator remembers someone telling him all it takes is a tiny puncture you’d never notice for bacteria to get in a beer can, and some bugs, you know, think beer is fine food.

Anyhow, Richie started acting weird. He stopped leaving the apartment. He sat in the dark, wouldn’t let Timmy turn on any lights. He even nailed blankets over the windows and broke the light fixture in the hall. A smell like spoiled old cheese hung over the place and grew steadily ranker. One night Richie told Timmy to turn on a light, and there he sat all covered in a blanket. He shoved out one hand, only it wasn’t a hand but a gray lump. He didn’t know what was happening to him, he said, but it felt… kinda nice. And when Timmy said he’d call their doctor, Richie shook all over and revealed his face—a still-recognizable mash buried in gray jelly, and Richie’s clothes sticking in and out of his skin, liking they were melting to his body.

If Timmy dared call the doctor, Richie would touch him, and then he’d end up just like Richie.

The trio mount Curve Street to Richie’s house, a monstrous Victorian now reduced to shabby apartments. Richie lives on the third floor. Before they enter, narrator asks for the end of Timmy’s story. Simple and terrible enough: Timmy got out of school early for the blizzard and arrived home to discover what Richie did while he was gone. Which was to crawl around, a gray lump trailing gray slime, prying boards from the wall to extract a well-putrified cat. For lunch.

After that, can they go on? Got to, Henry says. They have Richie’s beer.

The stench swells to gut-roiling intensity as they climb the stairs. In the third floor hall, puddles of gray slime seem to have eaten away the carpet. Henry doesn’t hesitate. Pistol drawn, he bangs on Richie’s door until an inhumanly low and bubbly voice answers, until squishing like a man walking through mud approaches. Richie demands his beer be pushed inside, tabs pulled—he can’t do it for himself. Sadly Henry asks, “It’s not just dead cats anymore, is it?,” and narrator realizes Henry is thinking of people who’ve gone missing from town lately, all after dark.

Tired of waiting for his beer, Richie bursts through the door, “a huge wave of jelly, jelly that looked like a man.” Narrator and Bertie flee out into the snow while Henry fires, all the way back to the Nite-Owl. In the space of a couple seconds, narrator has seen flat yellow eyes, four of them, with a white line between them and down the center of the thing, with pulsing pink flesh between.

The thing is dividing, he realizes. Dividing in two. From there into four. Eight. Sixteen —

No matter how the codgers who stayed behind at the store besiege them with questions, narrator and Bertie say nothing. They sit cozied up to plenty of beer and wait to see which one is going to walk in out of the storm, Henry or—

Narrator has multiplied up to 32,768 x 2 = the end of the human race. Still waiting. He hopes it’s Henry walks in. He surely does.

What’s Cyclopean: Even before we get to the Gray Monster, the descriptions of the weather are pretty intense in their own right. Snowdrifts look “like the backbone on a dinosaur.” Wind whoops and yowls, and feels like a sawblade.

The Degenerate Dutch: Per the entry for our last King story, “King’s working class characters are prone to racism, sexism, and a general background buzz of other isms.” In this case, we’re spared some of this by virtue of the lack of any on-screen characters who aren’t white men, but between them they manage some mild ableism at “Blind Eddy,” and some serious ableism and fat-phobia around Richie’s retirement.

Mythos Making: Things that are scary: fungus, old houses, cannibalism. (Is it still cannibalism if the eater isn’t human any more?)

Libronomicon: Timmy has some trouble doing his homework in the dark.

Madness Takes Its Toll: There’s things in the corners of the world that would drive a man insane to look ‘em right in the face.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Welcome back to Maine. It’s winter, better come into the bar where it’s warm. Settle down, listen to a story… maybe one a little more immediate than you were expecting. My favorite thing this week is how King plays with the Lovecraftian trope of the narrator telling you a story that he heard from a guy who heard it from the kid who experienced it—until it twists at the end into something happening directly to the narrator, and maybe, if things go very wrong, to the reader as well.

Beyond that, my reactions are, as usual with King, mixed. I love how closely he observes. I hate, sometimes, how closely he observes. I want to see the minute details of breath and body language as people react to the intrusion of the uncanny. I want the visceral sense of a rural blizzard, everyone huddled together against the vast force rising around them. I want the careful, quirky descriptions of individuals—until the moment where I’m tired of being in the head of one more small town white guy being judgy about everyone else’s imperfect bodies. It’s an exact and accurate depiction of a real way that real people think. It’s just not my favorite headspace to spend a story in, and it’s the headspace in which 90% of King stories take place. More vengeful teenage girls, please?

Yeah, let’s talk about the weather. I do love that blizzard. Actually, I’m pretty much a sucker for extreme weather atmospherics of any sort. One of my favorite old King stories that doesn’t involve vengeful outcast girls is “The Mist,” in which the titular precipitation covers a town (in rural Maine) and turns out to be full of weird extradimensional predators. Between that and Niven’s “For a Foggy Night,” I… probably should have developed a fog phobia, but in fact spent quite a lot of my teenage years wandering out into the stuff hoping to find a dimensional portal. There’s something inherently uncanny about this kind of weather, pathetic fallacy morphing into the natural assumption that weather bridges a boundary between the normal, predictable world and the supernatural one. Maybe I really am gothic at heart.

Back to the narrator, I rather like him in spite of myself. I’m not particularly a bar person, but a bar does make a good starting point for a small ensemble, the prototypical D&D party going to an Inn to meet a Man. And you have to somewhat appreciate a guy who’s willing to join the party, and go out into the snow after Things. Henry seems like a good party leader based on courage if not on common sense. After hearing the kid’s story, sure, he’s smart to take a pistol. You know what else would’ve been smart? A FLASHLIGHT THAT’S WHAT. A water pistol full of ice water. A flamethrower. Something vaguely related to the thing’s obvious dislikes, as opposed to a weapon intended to be used against entities with notable structural integrity.

I suppose that’s what you get, starting out in a bar. We sort of have a Cheers vs. The Picture in the House vibe going on. Probably a more even contest than anyone would prefer. Or not so even, since two thirds of the party ultimately turn and run as soon as the door opens, in true Lovecraftian fashion. Everyone wants to be a man of action, a Final Girl who stands and fights (and maybe wins), but at the end most would rather scamper and live to tell the half-glimpsed tale. Preferably back at the bar, where you’ve earned a lifetime of people buying your round. “Or whatever’s left” of that lifetime, as our narrator points out.

The ending is a gasp of apocalyptic horror, and a study in raising the stakes. For about ten seconds, until I consider: The thing can’t stand light or cold. And it’s snowing. The thing may be invulnerable to bullets, but it’s not going to get very far in a Maine winter. Whatever happened to Henry, you go back during daylight, and you cut the freaking gas lines and power to the house. Or knock out a window and borrow one of those horrible spotlights from your nearest construction crew. Dangerous confrontation, yes. Thirty-two-thousand, seven-hundred-and-sixty-apocalypse, probably not.

Anne’s Commentary

I love it when Stephen King lets us hang out with the Grand Old Codgers of Maine (honored members of the Fraternal Brotherhood of Grand Old Codgers of New England.) The unnamed narrator of “Gray Matter” is a prime example. The favored habitat of GOCs of ME (of GOCs, in general) is the general store or its equivalent: the diner, the coffee/donut shop, the corner bar or liquor store. Or, as here, the contemporary general store, the 24-hour convenience store. Like Lovecraft, an acknowledged influence, King has enjoyed inventing his own bedeviled towns and topography. I’m not sure if he means to set this story in any of his major creations. That Henry’s Nite-Owl is on “this side of Bangor” would rule out Jerusalem’s Lot and Castle Rock, I think, which are in the vicinity of Portland. [RE: That little side story about things that’ll drive you mad in the drains sounded an awful lot like It.] It could near Derry, which is itself either near Bangor or King’s own version of Bangor.

Needless to say, anything near Derry could harbor influences more than capable of contaminating beer, cheap or otherwise. Yes, college students of pretense. I don’t think you’re safe even if you stick to expensive imports or craft brews. Not purchased from purveyors of spirits within fifty miles of the Derry transdimensional epicenter, anyway. Just saying that spores from the Outer Spheres can travel across galaxies. What are a few townships to them? And is it not obvious that poor Richie Grenadine is suffering from an infestation by Larvae (or more correctly, a Larva) of the Outer Gods (specifically, of course, Azathoth, aka the Larvae-Spewer)? I mean, if you can’t see that, you need to retake Metaphysical Diagnostics 101.

There is room for the theory that Violet Carver of Seanan McGuire’s “Down, Deep Down, Below The Waves,” might have wondered whether Richie was a latent Deep One and dosed his beer with her Change-inducing elixir, only to discover that elixir plus cheap brewski produced shoggoth, not Deep One. Or maybe Richie was simply a latent shoggoth. That doesn’t seem unlikely from what we hear of him. Not that I wish to speak ill of the shoggothim by the comparison!

A nice contamination horror tale, but also a transformation tale, with the interesting twist of Richie kinda enjoying becoming a monster. Why not? His boring, gutted life is becoming one of growth, however fungal, and power beyond anything he ever flexed in the sawmill. Also, perhaps, the communion with untold others just like him, products of binary fission, Richies without end, amen, as long as there’s fermented nastiness enough to sustain them.

I guess I’m assuming Henry isn’t the one who walks back into the Nite-Owl. I guess he’d have walked in before narrator got into the thirty-thousands if he was still in any condition to walk. I guess narrator knows that, too.

Narrator himself is the best part of the story, with his GOC-typical habit of meandering off the straight and narrow plot-road into looping paths of reminiscence and more or less (generally more if you think about it) relevant anecdote. He follows in the noble tradition of Mark Twain’s Jim Blaine, whose infamous tale of the old ram never does get told what with all Jim’s superbly sericomic diversions into every other story he’s heard tell of in his long drunken life. However, King’s narrator doesn’t defuse suspense—he builds it, as when he interjects the story of the giant spider in the sewer between Richie pulling the blanket from his face and what Timmy saw when that face came in view. He doesn’t dilute theme or atmosphere—he intensifies them, again with the spider story (mind-wrecking things in the corners of the world) and the rotting dog story (connecting a wrenching emotional component with the physical hideousness of the stench in Richie’s house.)

To “Gray Matter’s” narrator, and to all the GOCs in King’s early masterpiece, ‘Salem’s Lot, and to his ultimate GOC, Jud Crandall of Pet Sematary, I raise a (very carefully presniffed) cold one! And more than happy to have Howard’s GOCs Ammi Pierce and Zadok Allen join us as well!

Next week, we dive back into the Miskatonic library stacks for Margaret Irwin’s “The Book.” You can find it in the Vandermeers’ The Weird anthology.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

It’s been a very, very long time since I read Night Shift; I need to revisit it one of these years. I find that King’s stories from that period tended towards the nastier end of the scale — possibly a combination of relatively short length, and the markets he was writing for at the time.

I’d also love to see a full-on reread of The Mist one of these times. (Unless there already was one that I commented on and have subsequently forgotten.)

This is pretty good early King. He’s almost got his voice nailed down, although he never quite hits that one perfect sentence as he so often does. This one is also unusually brief for him. I still say the novella is the perfect length for King. Reins him in while still giving him a little room to play.

As I read this, I kept thinking of another King story from just a couple of years late: “Weeds” (AKA “The Lonesome Death of Jordy Verrill”). “Weeds” hews a little closer to Lovecraft, specifically “The Colour Out of Space”, but at least Jordy doesn’t seem to revel in his transformation the way Richie does. In fact, in some ways it might have been more interesting to see this story from Richie’s point of view: bitter, resentful and a lot of other negatives. Let us see why he’s so willing to accept his transformation, where Jordy ultimately (though too late) rejects his and takes his own life.

Like Ruthanna, I immediately saw It in the narrator’s digression about the giant spider in the sewer. I’m going to disagree with her on the “serious ableism” directed at Richie. I’m pretty sure this is the sort of guy who has taken a workplace injury and parlayed into permanent disability checks that he doesn’t actually need or deserve and the whole town knows it. (And for the record, my uncle did exactly that. I know the mindset.) That’s one of the reasons seeing inside his head might improve this story.

Things that are scary: decay processes. From finding that the dead bird or cat you casually kick over has all manner of things moving around in it to forgetting to put some chow mein away after dinner and in the morning finding that it is boiling without heat. If a person becomes able to eat that sort of thing, they must not be human (anymore). Recall the narrator in “Heart of Darkness” throwing the crew’s food overboard because it was riper than what he liked to smell. Not-so-hidden message, “they” aren’t like “us”.

When anything in a horror story is said to smell bad, putrefaction is the simile of choice, so it seems. Of course, part of that is because for decades no one could write openly about excrement (decay par excellence.) One might be a bit rattled at finding that one’s cheese, kimchi or wine are made by similar fermentation processes, and that one’s steak is not actually fresh. Or that the gas that powers one’s bus was made by a landfill, the filthiest thing of all.

All right, it’s been a while since I read either Conrad’s work or King’s. But it seems to me that someone could do a whole thesis or something about the role of putrefaction/fermentation/anaerobic decay in horror fiction/mythology.

It’s clear from this that young Master Stephen drank a lot of very bad beer during his University of Maine college days. The description brings back personal memories of a Lovecraftian horror called Genesee Cream Ale, a brew no shoggoth would drink today.

I think I just read this earlier this year, while on a late night horror binge and scouring online libraries for stuff I hadn’t read yet. I mean, when you’ve already got insomnia, there’s not much point avoiding stuff that might make it hard to sleep, right?

Personally, I’m not much of a drinker, especially of beer. Beer all tastes the same to me, which is to say, “Like nasty yeast water.” I’m also allergic to some kinds of alcohol, so even more reason to stay away from the stuff.

I feel like I’m one of a small number of people who prefer King’s short fiction to his novels. It feels like his longer fiction can get bogged down with extraneous details, while stories like this one are more to the point and don’t overstay their welcome.

I don’t imagine Henry’s going to come walking back into the Nite-Owl, but I’m also not sure how far Amoeba!Richie is going to get if he/they can’t stand the cold, or the light. Narrator and Bertie might be waiting for a very long time.

The title had me thinking of brain matter, so I was assuming I hadn’t read this story until I hit the synopsis, and then remembered the general outlines of it.

Thinking about this makes me kind of miss early Stephen King, those stories that teetered on the brink between scary and just goofy, intentionally or inadvertently. The demon-possessed laundry mangler, upgrading itself to a more powerful demon by squishing some bats for bat blood! The ginormous rats and bats of the ‘Night Shift’ story itself!

If you all are not watching Castle Rock, you should. It is pretty cool, and make many many references to Kings early work. It’s been fun trying to catch them.

I had forgotten this story since it’s been close to 30 years since I read Night Shift. Great article.

Denise@5,

I’m with you on preferring King’s short work. Maybe, so I don’t have to be scared so long.

I’m surprised nobody (either the reviewers or the commenters) mentioned how this story is very clearly KIng doing a working-class riff on Arthur Machen’s “Novel of the White Powder”! I think there are enough similarities to be, at least, suspicious, and I rarely see that commented.

Other than that, you can count me in the minority who prefers King’s short fiction. “Night Shift”, particularly, is one of my favourite books of his (maybe even my favourite)

I could be talked into covering “The Mist” some time, though I’m a little nervous that it won’t live up to my teenaged recollections. Haven’t read that particular Machen, either, so that’s another for the list.

I would read–but probably not write–that thesis on the literature of rot.

Re: ableism. It’s hard for me to read the comments about Richie’s worker’s comp as being *only* about Richie’s personal laziness, given the “one of those people who” language. The implication is that most people who get injured on the job are just scammers. Plus this is a pattern for King. I’ll admit I haven’t been a completist (given my feelings about his writing) but I don’t think I’ve ever encountered a story of his where disability wasn’t treated as monstrous one way or another. It’s rarely egregious but the constant unexamined background assumption is grating.

I wasn’t injured on the job, but I do have a handful of chronic illnesses that could prevent me from holding a job (and technically already have). I’ve made the decision not to go on disability pay, even though I’m qualified to receive it. I still live with my parents, and get a lot of financial help from them, though I wish I didn’t need it, and as a result I’ve already been branded a “leech” by members of our extended family who don’t understand why I haven’t been able to make a living on my own.

So–yeah, the ableism is a concern. I didn’t really think of it much in regard to this particular story. There are other stories by King where it’s much more front and center, so to speak, and by contrast here it’s almost a throw-away detail (not that, “well, it could be worse,” is much of a point in its favor). But, yes, the very perspective of people living on disability who don’t “deserve” it is one of the reasons, though not the main one, that I haven’t pursued it.

No fear; “The Mist” still holds up and you guys should absolutely cover it.

Also, do “Jerusalem’s Lot”! I want to see your take on King deliberately writing a Lovecraft pastiche in his very best imitation of Lovecraft’s voice.

Just popping in to note that calculating up to 32768 might not take all that long even though the number seems large. After all, it is only 2 to the power of 15. I think most people could handle 15 doublings within one minute. Two at the most.

Good points on the ableism directed at Richie. Even if he is faking (which I think the reader is supposed to assume, if for no other reason than to reduce any potential sympathy for him), there’s still a fair amount of ableism behind the criticisms of him. There’s some classism there, too. For all King’s favorable views of blue collar people (and naming his son for one of the biggest names in the early struggle for labor rights tells us what he thinks), there is still a layer of poverty for the blue collar man to look down on. Given the extreme whiteness of Maine 40 or 50 years ago, those poor are where the blue collar Downeaster is going to look to feel better about his lot in life. Richie slots pretty well into that.

Did Richie cover himself with the blanket because he was cold or because he wanted to conceal himself and cut off light? If people have been vanishing at night, he’s been outside in weather that if not full blizzard condition is still going to be pretty damn cold. If those were alien spores and Richie is turning into something Shoggoth-like, the Shoggoths in MoM don’t seem much bothered by Arctic conditions. (The light still would be an issue, and I’d think gasoline and matches would prove useful. Or a truckload of Lysol.)

If eating corruption is inhuman, Sardinians are probably some sort of eldritch horrors.

Mmm, maggot cheese. A favorite of those Food Channel shows that feature intrepid hosts eating incredibly disgusting (to the American palate) comestibles. Perhaps only to be surpassed by Sweden’s “rotten herring” or surstroemming. Defenders of both these delicacies will say they’re not rotten, just fermented, but there’s a fine line between the two conditions, I think.

As for Richie’s disability, I’d say it’s genuine but not primarily the result of a physical injury. He was always a pig about his beer, we’re told. My diagnosis: untreated alcoholism. Alcoholism not only untreated but even shrugged off — no biggie that Richie puts away a case a night, that’s what the folks at Henry’s expect of someone like him, a worker guy just a tad more extreme about his consumption than his fellow worker guys who only put away a six pack a night or so.

King is sensitive to the pervasive horrors of addiction early on. Given his own struggles, he faces them with harrowing force in later work, like Doctor Sleep, and, come to think, in The Shining, of which Doctor Sleep is the sequel.

That’s a good point–I hadn’t thought about the ways Richie might involve King dealing with his own demons. It’s been too long since I read On Writing (which I actually do love).

Atlas @@@@@ 9: By golly, I think you’re right and as a long-time Machen reader, I’m a little surprised at myself that I never thought of the connection. If this wasn’t an intentional homage to the White Powder, it may at the least have been an unconscious inspiration.

Ruthanna @@@@@ 10: ‘The Novel of the White Powder’ is one of the episodes of The Three Impostors (why yes, I’m a rabid fan of Arthur Machen) and if you’re going to read it, you should do a full review of The Three Impostors – perhaps as a multi-part review, befitting the story-within-stories nature of it. It’s quite an amazing confection of story-telling and lies, probably his best creation.

There was also an incredible novel-length homage to The Three Impostors written a while back, worthy of review in itself, but I can’t think of either author or title right now. I’ll have to find it later.

@16 Anne, I did wonder if some of Richie’s portrayal/characterization had to do with King’s own experience. Though, I don’t know where this story falls in his career and what was going on in his life at the time. Being published in 73, it would be pre-Cujo, which if I remember correctly is the book he has said he has no memory of writing, because he was blackout drunk and/or stoned the whole time (and personally, I think it takes guts to admit something like that).

Even if he was still in the “denial” stage at the time, it still could have had a subconscious effect on the story, though.

People keep telling me to read On Writing, but I haven’t gotten around to it yet!

King’s non-white characters being Magical Negros whose only purpose in life is to help the white middle class protagonist, that’s a blessing.

Yes, I despise King. The only reason I read hon is to remind myself how not to write.