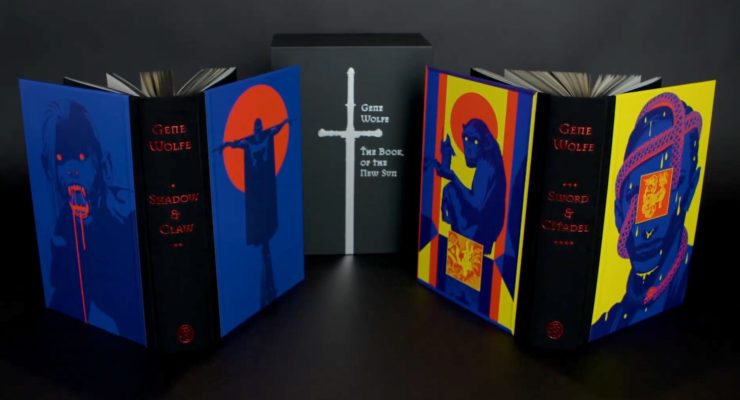

For several years now, The Folio Society has been releasing some stunning editions of science fiction’s classic novels: Recent editions have included the likes of George R.R. Martin’s Song of Ice and Fire series, Robin Hobb’s Farseer trilogy, Arthur C. Clarke’s Rendezvous with Rama, and many others.

The publisher just released its spring collection, and included in it is a new, two-volume edition of Gene Wolfe’s The Book of the New Sun, with illustrations from Sam Weber. I spoke with Weber about his artwork, and how he interpreted the text through his art.

Weber is no stranger to The Folio Society: He illustrated art for the publisher’s edition of Dune, which largely kicked off their science fiction offerings in 2015. Back in 2019, The Folio Society published Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun as a four volume limited edition, and now, it’s released the series as a more compact two-volume set. The first volume, Shadow & Claw includes the first two books: The Shadow of the Torturer and The Claw of the Conciliator, while volume two, Sword & Citadel, contains The Sword of the Lictor and The Citadel of the Autarch.

Weber provided illustrations for the novel—and has some prints up for sale on his site—and spoke with me about what inspired the art for the set. (Replies have been edited for clarity.)

You’ve worked with the Folio Society before with their edition of Frank Herbert’s Dune. What was appealing to you about illustrating Gene Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun?

I think largely what was so exciting about illustrating The Book of The New Sun was the opportunity it gave me to further unravel the book’s many mysteries. Wolfe’s writing is so precise and intentional. I found that many of the clues presented within the text gained a certain type of clarity when explored visually, partly because the process of illustrating a book requires one to read very carefully. The text’s evasive nature and Severian’s unreliability is of course such a huge part of the work’s effectiveness.

I found myself often asking “what is Severian actually looking at here?” What can be accepted or left unanswered as a reader isn’t always possible when painting a scene, since the nature of a narrative painting requires the artist to have a specific understanding of what is actually happening and that I think was what became so exciting about this project. Although other endeavors of course require a similar level of attention and thought, I don’t think I’ve ever been rewarded with more unexpected surprises.

From the satellite dishes in The Atrium of Time to the Mirror Chamber in The House Absolute (which in hindsight I think I may have envisioned incorrectly), this kind of careful reading opened the book up for me in a way that was deeply rewarding.

I think Wolfe was also incredibly astute visually, and drew deeply upon a wide array of art historical sources.

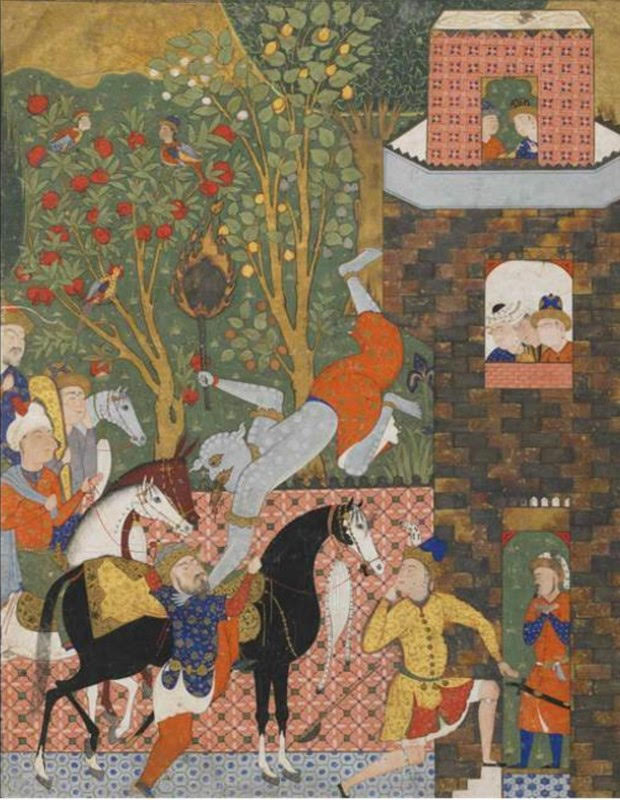

There’s a passage in Sword of The Lictor, during the fight with Baldanders, that I think exemplifies the depth of Wolfe’s relationship to art history so clearly for me:

“There are pictures in the brown book of angels swooping down upon Urth in just that posture, the head thrown back, the body inclined so that the face and the upper part of the chest are at the same level. I can imagine the wonder and horror of beholding that great being I glimpsed in the book in the Second House descending in that way; yet I do not think it could be more frightful. When I recall Baldanders now, it is thus that I think of him first. His face was set, and he held upraised a mace tipped with a phosphorescent sphere.”

As an illustrator, I read this passage very closely while considering the possibility of illustrating this scene. “What angels?” I kept asking myself. I remember sitting in my studio trying to envision the drama. After some time, it occurred to me that maybe Wolfe was in fact referencing an actual image from art history. I combed through various renaissance and medieval depictions of angels, assuming perhaps he was referencing a piece of Christian art. I had just about given up, when I stumbled upon this startling painting:

I felt like I’d been punched in the chest. There is a flaming mace, quite similar to Baldanders’. A castle tower and soldiers storming it. A tree with three mysterious winged alien figures perched inside, a man dropping a black sword (just like Severian drops Terminus East). Is this the image Severian recalls from the brown book? Did Wolfe structure the entire scene on this painting???

This wonderful illuminated page is from The Falnama, created in around the 16th or 17th century. A little internet searching found this from an exhibit a few years back “Whether by consulting the position of the planets, casting horoscopes, or interpreting dreams, the art of divination was widely practiced throughout the Islamic world. The most splendid tools ever devised to foretell the future were illustrated texts known as the Falnama (Book of Omens). Notable for their monumental size, brilliantly painted compositions, and unusual subject matter, the manuscripts, created in Safavid Iran and Ottoman Turkey in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, are the center piece of Falnama: The Book of Omens.”

What does this say about The Brown Book? I feel like in some ways it reveals more questions than answers, which I guess is what I love so much about Wolfe’s work: The more you discover, the more mysterious and wonderful things seem to become.

When did you first read Book of the New Sun, and what did you come away from it with when you read it?

I read The Shadow of The Torturer for the first time around 2011 or so, knowing essentially nothing about Gene Wolfe or his work. I mistakenly started reading it as a fairly straightforward science fiction novel and took most of the text at face value. It wasn’t until The Claw of The Conciliator that it started to become apparent that there was so much more going on, that Severian was unreliable as a narrator, and that the author was purposefully concealing profoundly disturbing things within seemingly innocuous moments.

In hindsight part of me feels that the violence and brutality of the text is actually a bit of a smoke screen for the truly sad and dark themes within the story. I don’t think I really understood much this on my first read. It wasn’t until I read the book for a second time that I began to really get what was happening.

Your work for Dune was vibrant and colorful; the illustrations here are—with a couple of exceptions—muted and in dull, grey tones. What prompted this color scheme?

Part of that decision was purely practical: At one point Sheri Gee, the art director, and I decided that the majority of the illustrations would be in black and white. While exploring different ways of making the paintings, I started to really enjoy this low contrast, muted approach.

I felt it worked on an emotional level and enjoyed how things became harder to see. I liked this idea of creating images from a dim world, where light and the sun is not as readily present as it is in our world. By contrast I wanted the covers to feel kind of insane and vibrant, I liked that tension for some reason.

What do you hope to convey to the reader with each image?

Hopefully, in a few instances, some clarity or truth about the text that is not readily apparent. There are all kinds of great feelings to be experienced while reading this book—unease, the tension between attraction and alienation, the sense of there being an answer just out of reach.

I hope my paintings support those feelings and don’t undermine the wonderful sense of mystery that is so special to Wolfe’s writing.

It feels like there’s a bit more of a surrealistic feel to these images as well. How did you go about selecting the scenes for each image?

I actually think I tried to treat these paintings quite literally. If I’m being honest, I think any sense of surrealism has more to do with Wolfe’s ideas than anything I was actively trying to do. I largely followed my own interests when selecting what to illustrate.

In the case of The Atrium of Time painting, or Jonas and The Mirrors, I wanted to show a possible answer to one of the many riddles Wolfe has left us. The painting of Severian and The Undine I think was more about showing the beauty and magic of the scene. Beyond selecting moments that would allow for an even distribution of illustrations throughout the book, I essentially just chose my favorite moments and characters, which I would say is pretty typical of my work for The Folio Society.