When I first read Slaughterhouse-Five, I felt a little cheated by Kurt Vonnegut. The summarized stories of the character Kilgore Trout all sounded amazing to me, and at 17 years-old, I wanted to read the full versions of those stories. Later, as a more grown-up person, I realized I may have missed the point of the Kilgore Trout device and chided myself for having wanted to read the fake-science fiction stories in a real-science fiction context.

But now, with the release of a new collection of short fiction out this week from Etgar Keret, I feel as though a childhood fantasy has nearly been fulfilled. If Kilgore Trout had been a real person, and his brief stories presented on their own*, they would have been close cousins of the stories of Etgar Keret.

(*I don’t count Venus On the Half Shell by “Kilgore Trout,” because it does not come from Vonnegut, nor the alternate dimension where Kilgore Trout is real.)

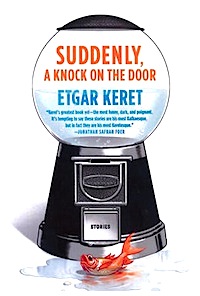

It’s impossible to talk about Keret’s stories without talking about their length. His latest, Suddenly, A Knock On the Door, is only 188 pages, but contains 35 stories so you do the math; the stories are really, really short, and like in previous collections, sometimes just a single page long. This has the deceptive effect of making you feel as though the book will be a breezy read. The collection is a fast read, but I wouldn’t call it an easy, breezy one. And that’s because these stories hurt a little bit. After a while, I started to sense each story coming to a painful, and odd end, making me almost afraid to turn the page. This isn’t because the stories contain any conventional plot stuff, but instead because they often start funny, before veering dark unexpectedly.

The funny and dark turns in the stories are both often reliant on elements of fantasy. In “Unzipping” the main character of the story discovers her lover has a zipper, which allows her to remove his current outward appearance, causing him to shed his previous personality and name, thus becoming a completely new person. Initially, I was giggling a little at the inherent cleverness of this concept, until the notion of the character discovering her own zipper was broached, and then the pain of the story became real. The essential identity of what makes us who we are is messed with in a lot of Keret’s stories, and “Unzipping” is one in which the fantasy concept of zipping off our skin makes it painfully obvious.

This isn’t the first time Keret has prodded the slippery definitions of our personalities by implementing massive physically changes in the characters, but there’s something more subtle about it in some of the stories in this collection. In “Mystique” a character overhears the phone conversation of a fellow passenger on a plane, but the specifics of the phone conversation seem to be borrowed from the narrator’s life. In “Shut” a man invents a different biography for himself than the one which really exists, while the story “Healthy Start” features a character who fakes his way through conversations with strangers, all of whom assume they’ve already arranged anonymous meeting with him. These stories all seems to orbit the idea that our identities are always on the edge of some kind of whirlpool or black hole which can easily strip away this whole “individuality” thing we’re all clinging to.

Other stories in the collection play with the fantastic in a more direct way. In “One Step Beyond” a paid assassin discovers his own personal versions of hell resembles the environment of a well-known children’s story. Meanwhile, the excellent “September All Year Long” gives us a machine (affordable only by the very wealth) which allows for absolute weather control. This one reminded me of mash-up between Steven Millhauser’s “The Dome” and Philip K. Dick’s “The Preserving Machine” because it used an element of magical realism casually and chillingly like Millhauser, but held the human users and creators of the bizarre invention accountable, like Philip K. Dick would. It’s here where Etgar Keret emerges as something of a science fiction writer; he comments directly on what our inventions might do to us if they were more extreme than the ones we actually have now. This is where I find him to be the healthier, happier, real-life version of Kilgore Trout. He’s a bit of a mad scientist, creating odds and ends in his story laboratory, with each new invention startling the reader a little more than the last.

But more than a love of the fantastic, Keret’s latest collection highlights his belief that the stories themselves are his greatest mad scientist inventions. In “The Story Victorious,” Keret describes the story as a kind of device, an actual, physical thing, incapable of rusting or wearing down. Again, shades of Philip K. Dick’s “The Preserving Machine” are here, insofar as Keret depicts fiction/art as the ultimate science fiction invention of them all. And the story described in “The Story Victorious” is also fluid and changing, and will, in fact, listen to its reader. Depending on how the story strikes you, you may be tempted to tell this book some of your troubles. Meanwhile, a story called “Creative Writing” offers us a woman taking a creative writing course in which she writes almost exclusively science fiction stories, which feels like the best sort of literary comfort food. But at the same time, each of her stories feels like a functioning little device she’s brought into the world.

In one of the longer stories in the book, “What Of This Goldfish Would You Wish?” a talking, magical goldfish capable of granting three wishes takes center stage. As a reader of the fantastic, I think everyone would be wise to waste at least one of their wishes on more stories by Etgar Keret. I mean, it couldn’t hurt, and we’d still have two left.

Ryan Britt is the staff writer for Tor.com. He is the creator and curator of Genre in the Mainstream. He first interviewed Etgar Keret back in 2010 on the subject of science fiction for Clarkesworld Magazine. He ends up calling poor Etgar a “mad scientist” nearly every time he writes about him. Sorry!