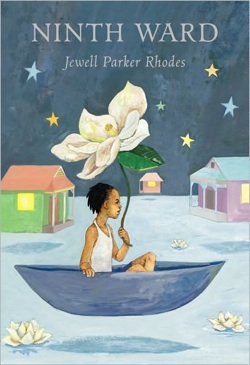

This week, as news of Hurricane Irene and its aftermath continues to trickle through my Facebook and Twitter feeds, I’ve found myself turning to a novel set during another hurricane that filled the news six years ago: Ninth Ward, by Jewell Parker Rhodes.

Twelve-year-old Lanesha sees ghosts. Her mother, who died in childbirth at seventeen, and who still hangs around the house, “her belly big, like she’s forgotten she already gave birth to me. Like she’s stuck and can’t move on. Like she forgot I was already born.” Figures from the past of her city, New Orleans, a place soaked in history: “Ghosts wearing yellow silk ball gowns with flowers in their hair, and waving silk fans. Cool men who wore their hats slanted to make them look slick.” And then there are the more recent arrivals: “Ghosts in baggy pants, their underwear showing, wearing short-sleeve T-shirts and body tattoos mostly boys killed in drive-bys or fights or robberies. Sometimes, I know them from school. Like Jermaine. One day I’m seeing him in the cafeteria eating macaroni, the next day, he’s a ghost, dull eyed, high-fiving me, saying, ‘Hey, Lanesha.'”

Lanesha’s guardian, an 82-year-old midwife and wise woman she calls Mama Ya-Ya, says she has the sight. Her classmates call her crazy, spooky, a witch. Her teachers encourage her, tell her she’s smart, could go to college and be an engineer. Lanesha dreams of building bridges, loses herself in math problems and books from the library. She yearns for friends, for acceptance by the Uptown family who refused to claim her, but she loves Mama Ya-Ya, who loves her and cares for her and teaches her to read dreams and symbols. They don’t have any money, but they have each other, and their ramshackle Ninth Ward house.

Of course, we know what’s coming next, even if Lanesha doesn’t. Everyone says the hurricane’s going to be a bad one. Unfathomable destruction, says the television. Mama Ya-Ya’s dreams tell her that the storm won’t be too dangerous, but something else will, only she can’t see what: in the dream, everything goes black, “like God turning out the lights.”

School is cancelled. The mayor announces a mandatory evacuation. (“How can it be mandatory if I don’t have a way to go?” mutters Mama Ya-Ya.) Neighbors start to pack up and leave. Mama Ya-Ya and Lanesha prepare to weather the storm, as they’ve done before. And the ghosts begin to gather, in the living room and in the neighborhood. “I’m used to seeing a random one now and again,” Lanesha says, “but tonight it feels crowded.” As her neighbor Mrs. Watson prepares to leave with her family, Lanesha sees the dead Mr. Watson “shaking his head, standing behind Mrs. Watson. He’s trying to comfort her, but she’s too busy worrying about me to feel him. Most people would feel ghosts if they let themselves. But most folks are ignorant on purpose or else too busy, too scared. Real folks ignore any kind of magic.”

Based on the topic and the back-cover copy, it would be easy to mistake this book for a problem novel, a historical after-school special. It’s not. Not just because of the ghosts, or the gorgeous, dream-like prose, but because it’s not really the story of Hurricane Katrina, and doesn’t pretend to be: though we hear snippets of other stories (her friend TaShon has fled from the chaos of the SuperDome and walked across town to his old neighborhood), this book is about Lanesha and her singular experience, which encompasses everything with equal vividness: the fresh-ink smell of her new pre-algebra book; the smile of a ghost girl skipping rope; the red welts that rise on TaShon’s legs when he cools them in the dirty flood water.

Magic can’t save Lanesha from the hurricane, or from the flooding that comes afterward and forces her to retreat to the second floor, then to the attic. Or from grief, or death. Eventually, she and TaShon flee to the roof, where they wait in vain for rescue. At a crucial moment, the ghosts do matter, but Lanesha also owes her survival to the love and skills and faith in herself that Mama Ya-Ya has given her. The two strands of her strength—love and ghosts, past and present, magic and practicality—are intertwined and inextricable.

Elisabeth Kushner is a writer and librarian who lives in Vancouver, British Columbia. She’s grateful that her Vermont and other East Coast family and friends are okay this week.