There’s a current pattern in male protagonists of otherwise excellent contemporary British fantasy and SF novels that kind of drives me nuts. It seems as if the trend is for these fictional men to come across as narcissistic, self-pitying, and incredibly judgmental.

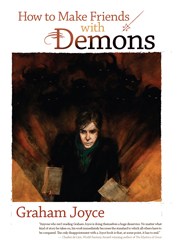

Unfortunately, the protagonist of How to Make Friends with Demons is no exception.

Don’t get me wrong: Graham Joyce is a brilliant writer. His prose is pellucid, his ideas engaging, his characters crisply drawn. This book has texture, nuance, and guts.

It’s just that I want to stab his protagonist with a fork until he pokes his head outside his own little alcoholic bubble of self-imposed misery and takes notice of something. Preferably something other than an attractive and selfless woman—although, as much as the gender politics of that trope frustrate me I must admit it is in large part an image drawn from life, and there are enough self-aware, agenda-driven females in Joyce’s universe to mitigate my irritation a great deal.

My irritation is also mitigated by the fact that the narrative—

Oh, wait. Maybe I should actually do a little exposition before I continue this rant.

So you know what I’m talking about, at least.

William Heaney is a high-level government functionary. He’s also an alcoholic, a grifter, a divorcee, the chief contributor to a charity shelter, the estranged father of several more-or-less adult children, and a man who can see demons. Real demons, though whether they have objective existence or are merely concretized metaphors conjured by his diseased mind is left as a (deeply thematic) exercise for the reader.

When a homeless veteran gives William a strange diary and then blows himself up, William finds himself revisiting dark secrets of his past while simultaneously attempting to wrest control of the shambles that is his daily life. It may be (indirectly) his fault that a series of women have died; his teenaged son is maturing into a despicable adult; his ex-wife has remarried a pompous celebrity chef; and the artist who is creating the forgery he desperately needs to sell has become unreliable due to romantic troubles of his own.

…and that’s the first fifty pages or so.

This is not a slowly-paced book, as you may have gathered.

In any case, William is a twit. He’s judgmental, self-absorbed, self-righteous, and generally desperately in need of a codslap.

His twithood is mitigated by his generosity, however. And he is redeemed as a protagonist by the fact that the book he inhabits exists for precisely the reason of providing that codslap. Suffice it to say, by the final pages, the metaphor of demons is elaborated, the mysterious history is unpacked, and William suffers, if not an epiphany, at least a leavening of self-knowledge.

It’s a good book. Even if it did make me ranty as hell.

Elizabeth Bear lives in Connecticut and rants for a living.