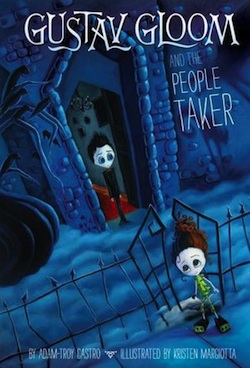

We’re super excited to give you this two chapter peek at Gustav Gloom and the People Taker by Adam-Troy Castro, just released from Penguin Young Readers!

Meet Gustav Gloom.

Fernie What finds herself lost in the Gloom mansion after her cat appears to have been chased there by its own shadow. Fernie discovers a library full of every book that was never written, a gallery of statues that are just plain awkward, and finds herself at dinner watching her own shadow take part in the feast!

Along the way Fernie is chased by the People Taker who is determined to take her to the Shadow Country. It’s up to Fernie and Gustav to stop the People Taker before he takes Fernie’s family.

Chapter One

The Strange Fate of Mr. Notes

The neighbors thought Gustav Gloom was the unhappiest little boy in the world.

None of them bothered to talk to him to see if there was anything they could do to make his life better. That would be “getting involved.” But they could look, and as far as they could see, he always wore his mouth in a frown, he always stuck his lower lip out as if about to burst into tears, and he always dressed in a black suit with a black tie as if about to go to a funeral or just wanting to be prepared in case one broke out without warning.

Gustav’s skin was pale, and he always had dark circles under his eyes as if he hadn’t had enough sleep. A little quirk of his eyelids kept them half closed all the time, making him look like he wasn’t paying attention. His shiny black hair stood straight up, like tar-covered grass.

Everybody who lived on Sunnyside Terrace said, “Somebody ought to do something about that sad little boy.”

Of course, when they said somebody ought to do something, they really meant somebody else.

Nobody wanted to end up like poor Mr. Notes from the Neighborhood Standards Committee.

Mr. Notes had worked for the little town where they all lived. His job was making sure people took care of their neighborhoods, and the neighbors on Sunnyside Terrace had asked him to visit the Gloom house because it didn’t fit the rest of the neighborhood at all.

All of the other houses on Sunnyside Terrace were lime green, peach pink, or strawberry red. Each front yard had one bush and one tree, the bush next to the front door and the tree right up against the street. Anybody who decided to live on the street had to sign special contracts promising that they wouldn’t “ruin” the “character” of the “community” by putting up “unauthorized trees” or painting their front doors “unauthorized colors,” and so on.

The old, dark house where Gustav Gloom lived had been built long before the others, long before there was a neighborhood full of rules. It was a big black mansion, more like a castle than a proper house. There were four looming towers, one at every corner, each of them ringed by stone gargoyles wearing expressions that suggested they’d just tasted something bad. There were no windows on the ground floor, just a set of double doors twice as tall as the average man. The windows on the upper floors were all black rectangles that might have been glass covered with paint or clear glass looking into absolute darkness.

Though this was already an awful lot of black for one house, even the lawn surrounding the place was black, with all-black flowers and a single black tree with no leaves. There was also a grayish-black fog that always covered the ground to ankle height, dissolving into wisps wherever it passed between the iron bars of the fence.

The lone tree looked like a skeletal hand clawing its way out of the ground. It was home to ravens who seemed to regard the rest of the neighborhood with as much offense as the rest of the neighborhood regarded the Gloom house. The ravens said caw pretty much all day.

The neighbors didn’t like the ravens.

They said, “Somebody ought to do something about those ravens.”

They didn’t like the house.

They said, “Somebody ought to do something about that house.”

They didn’t like the whole situation, really.

They said, “Somebody ought to do something about those people, with their strange house and their big ugly tree that looks like a hand and their little boy with the strange black hair.”

They called the mayor’s office to complain. And the mayor’s office didn’t know what to do about it, so they called the City Planning Commission. And the City Planning Commission called Mr. Notes, who was away on his first vacation in four years but whom they made a point of bothering because nobody

liked him.

They asked Mr. Notes, “Will you please come back and visit the people in this house and ask them to paint their house some other color?”

And poor Mr. Notes, who was on a road trip traveling to small towns all over the country taking pictures of his one interest in life, antique weather vanes shaped like roosters, had folded his road map and sighed. “Well, if I have to.”

On the morning Mr. Notes pulled up to the curb, five-year-old Gustav Gloom sat on a swing hanging from the big black tree, reading a big black book.

Mr. Notes was not happy about having to walk past the boy to get to the house because he didn’t like little boys very much. He didn’t like little girls very much, either. Or, for that matter, most adults. Mr. Notes liked houses, especially if they matched the rest of their neighborhoods and had great weather vanes shaped like roosters.

Mr. Notes was so tall and so skinny that his legs looked like sticks. His knees and elbows bulged like marbles beneath his pin-striped, powder-blue suit. He wore a flat straw hat with a daisy in the band and had a mustache that looked like somebody had glued paintbrush bristles under his nose.

He opened the iron gate, expecting it to groan at him the way most old iron gates do, but it made no sound at all, not even when he slammed it shut behind him. He might have been bothered by the lack of any clang, but was even more upset by the odd coldness of the air inside the gate. When he looked up, he saw a big, dark rain cloud overhead, keeping any direct sunlight from touching the property.

He did not think that maybe he should turn around and get back in his car. He just turned to the strange little boy on the swing and said, “Excuse me? Little boy?”

Gustav looked up from the big fat book he was reading, which, like his house, his clothes, and even his tree, was all black. Even the pages. It looked like too heavy a book for a little boy to even hold, let alone read. He said, “Yes?”

Some conversations are like leaky motorboats, running out of fuel before you even leave the dock. This, Mr. Notes began to sense, was one of them. He ran through his limited collection of appropriate things to say to children and found only one thing, a question that he threw out with the desperation of a man terrified of dogs who tosses a ball in the hope that they’ll run away to fetch it: “Are your mommy and daddy home?”

Gustav blinked at him. “No.”

“Is—”

“Or,” Gustav said, “really, they might be home, wherever their home is, but they’re not here.”

“Excuse me, young man, but this is very serious. I don’t have time to play games. Is there anyone inside that house I can talk to?”

Gustav blinked at him again. “Oh, sure.”

Mr. Notes brushed his stiff mustache with the tip of a finger and turned his attention to the house itself, which if anything looked even bigger and darker and more like a giant looming shadow than it had before.

As he watched, the front doors swung inward, revealing a single narrow hallway with a shiny wooden floor and a red carpet marking a straight path all the way from the front door to a narrower opening in the far wall.

Whatever lay beyond that farther doorway was too dark to see.

Mr. Notes sniffed at Gustav. “I’m going to tell your family how rude you were.”

Gustav said, “Why would you tell them that when it isn’t true?”

“I know rudeness when I see it.”

“You must not have ever seen it, then,” Gustav said, “because that’s not what I was.”

Mr. Notes could not believe the nerve of the little boy, who had dared to suggest that there was any problem with his manners. What he planned to say to the people inside would ruin the boy’s whole day.

He turned his back on the little boy and stormed up the path into the house, getting almost all the way down the corridor before the big black doors closed behind him.

Nobody on Sunnyside Terrace ever figured out what happened during Mr. Notes’s seventeen minutes in the Gloom mansion before the doors opened again and he came running out, yelling at the top of his lungs and moving as fast as his long, spindly legs could carry him.

He ran down the front walk and out the gate and past his car and around the bend and out of sight, never to be seen again on Sunnyside Terrace.

When he finally stopped, he was too busy screaming at the top of his lungs to make any sense. What the neighbors took from it, by the time he was done, was that going anywhere near the Gloom house had been a very bad idea, and that having it “ruin” the “character” of the neighborhood was just the price they’d have to pay for not having to go anywhere near the house themselves.

Mr. Notes was sent to a nice, clean home for very nervous people and remains there to this day, making pot holders out of yarn and ashtrays out of clay and drawings of black circles with black crayons. By happy coincidence, his private room looks out upon the roof and offers him a fine view of the building’s weather vane, which looks like a rooster. It’s fair to say that he’s gotten what he always wanted.

But one strange thing still puzzles the doctors and the nurses at the special home for people who once had a really bad scare and can’t get over it.

It’s the one symptom of his condition that they can’t find in any of their medical books and that they can’t explain no matter how many

times they ask him to open his mouth and say ah, the one thing that makes them shudder whenever they see all his drawings of a big black shape that looks like an open mouth.

It was the main reason that all the neighbors on Sunnyside Terrace, who still said that “somebody” had to do something about the Gloom house, now left it alone and pretended that it had nothing to do with them.

And that was this: No matter how bright it is around him, wherever he happens to be, Mr. Notes no longer casts a shadow.

Chapter Two

The Arrival of Fernie What

Like always, Mr. What was careful to make sure his daughters weren’t worried.

He said, “Don’t worry, girls.”

Neither ten-year-old Fernie nor her twelve-year-old sister, Pearlie, who were riding in the backseat while their dad drove to the family’s new home on Sunnyside Terrace, had said anything at all about being worried.

They rarely said anything of the sort.

But their dad had always been under the impression that they were frightened little things who spent their lives one moment away from panic and were only kept calm by his constant reassurances that everything was going to be all right.

He thought this even though they took after their mother, who had never been scared of anything and was currently climbing the Matterhorn or something. She was a professional adventurer. She made TV programs that featured her doing impossibly dangerous things like tracking abominable snowmen and parachuting off waterfalls.

“I know it looks like I made a wrong turn,” he said, regarding the perfectly calm and sunny neighborhood around them as if giant people-eating monsters crouched hidden behind every house, “but there’s no reason for alarm. I should be able to turn around and get back on the map any second now.”

The What girls, who looked like versions of each other down to their freckled cheeks and fiery red hair, had spent so much of their lives listening to their father’s warnings about scary things happening that they could have grown up in two different ways: as scared of everything as he was, or so tired of being told to be scared that they sought out scary things on general principle the way their mother did.

The second way was more fun. Right now, Fernie was reading a book about monsters who lived in an old, dark house and took unwary kids down into its basement to make them work in an evil robot factory, and Pearlie was playing a handheld video game about aliens who come to this planet to gobble up entire cities.

The final member of the family, Harrington, wasn’t worried, either. He was a four-year-old black-and-white cat enjoying happy cat dreams in his cat carrier. Those dreams had to do with a tinier version of Mr. What making high-pitched squeaks as Harrington batted at him with a paw.

“Uh-oh,” Mr. What said. And then, quickly, “It’s no real problem. I just missed the turnoff. I hope I don’t run out of gas; we only have three quarters of a tank left.”

Mr. What was a professional worrier. Companies hired him to look around their offices and find all the horrible hidden dangers that could be prepared for by padding corners and putting up warning signs. If you’ve ever been in a building and seen a safety railing where no safety railing needs to be, just standing there in the middle of the floor all by itself as if it is the only thing that keeps anybody from tripping over their own feet, then you’ve probably seen a place where Mr. What has been.

Mr. What knew the hidden dangers behind every object in the entire world. It didn’t matter what it was; he knew a tragic accident that involved one. In Mr. What’s world, people were always poking their eyes out with mattress tags and drowning in pudding cups.

If people listened to everything he said, they would have spent their entire lives hiding in their beds with their blankets up over their heads.

Mr. What switched on the left-turn signal and explained, “Don’t worry, girls. I’m just making a left turn.”

Pearlie jabbed her handheld video game, sending another ugly alien to its bloody doom. “That’s a relief, Dad.”

“Don’t hold that thing too close to your face,” he warned. “It gives off lots of radiation, and the last thing you want is a fried brain.”

Fernie said, “Gee, Dad, can we have that for dinner tonight?”

“Have what?” he asked, jumping a little as the car behind him beeped in protest at him for going twenty miles an hour under the speed limit.

“A fried brain. That sounds delicious.”

Pearlie said, “That sounds disgusting.”

Coming from her, that wasn’t a complaint. It was a compliment.

Mr. What said, “That was very mean of you, Fernie. You’ll give your sister nightmares by saying things like that.”

Pearlie hadn’t suffered a nightmare since she was six.

“And Fernie, don’t make a face at your sister,” Mr. What continued, somehow aware that Fernie had crossed her eyes, twisted her lips, and stuck her tongue out the side of her mouth. “You’ll stick that way.”

Mr. What had written a book of documented stories about little girls who had made twisted faces only to then trip over an untied shoelace or something, causing their faces to stick that way for the rest of their lives, which must have made it difficult for them to ever have a social life, get a job, or be taken seriously.

Fernie and Pearlie had once spent a long afternoon testing the theory, each one taking turns crossing her eyes, sticking out her tongue, and stretching her mouth in weird ways while the other slapped her on the back at the most grotesque possible moments.

They’d both been disappointed when it hadn’t worked.

Mr. What said, “Hey, we can see our new house from here!”

Both girls saw the big black house behind the big black gates and started shouting in excitement: Fernie, because she loved the idea of living in a haunted house, and Pearlie because she loved the idea of living in any house that was black and mysterious, whether it was haunted or not.

Mr. What naturally assumed that the girls were screaming in terror instead of enthusiasm. “Don’t worry,” he said as he pulled into the driveway directly across the street. “It’s not that one. It’s this one, here.”

Now that the girls saw which house their father had really been talking about, they gaped in scandalized horror. “What color is that?”

“Fluorescent Salmon,” said Mr. What.

The little house did indeed look like the fish when it’s put on a plate to eat, only more sparkly, which might be perfectly fine inside a fish, but not so good, as far as the girls were concerned, on a house.

Fluorescent Salmon, it turned out, was just the right color to give Fernie What a pounding headache. “I’d rather live in the scary house.”

Mr. What looked at the big black house as if seeing it for the first time. “That broken-down old place? I’m sure all the rooms are filled with spiderwebs, all the boards in the floors have pointy nails sticking out of them, and the staircases have plenty of broken steps that will collapse under your weight and leave you hanging for your life by your fingernails.”

Both girls cried, “Cool!”

Gustav Gloom stood behind the iron fence of the Gloom mansion, watching the new neighbors emerge from their car. His mouth was a thin black line, his eyes a pair of sad, white marbles. Standing behind the long black bars—and going unnoticed by the girls, for the moment—he looked a little like a prisoner begging to be let out.

He had grown quite a bit since the day five years earlier when Mr. Notes came to call. He was skinny, but not starved; pale as a sheet of blank paper, but not sickly; serious, but not grim. He still wore a plain black suit with a black tie, and his black hair still stood straight up like a lawn that hadn’t been mowed recently.

He still looked like the unhappiest little boy in the world, only older.

The What family can be forgiven for not seeing him right away, in part because they were busy dealing with the business of moving into their new house, and in part because it was pretty hard to see Gustav in his black suit standing on his black lawn under the overcast sky over the Gloom residence.

It was just like the big black book Gustav still carried around wherever he went. Most people can’t read black ink on black paper. Seeing Gustav could be just as difficult, even on a sunny day when the whites of his eyes stood out like Ping-Pong balls floating in a puddle of ink.

An odd black smoke billowed at his feet. It moved against the wind, and sometimes, when it got enough of itself bunched up around his ankles, his legs seemed to turn transparent and fade into nothingness just below the knees. It was a little like he was standing on the lawn and in an invisible hole at the same time.

There were other patches of blackness darting around the big black lawn, some of them large and some of them small—all of them hard to see against the ebony grass. But all of them seemed as interested as Gustav Gloom in the doings across the street.

One of those dark shapes left the black house and slid across the black grass, stopping only when it found Gustav watching the two What girls and their incredibly nervous father unload cardboard boxes from the trunk of their car.

To both Gustav and the shape that now rose from the ground, the girls were bright in ways that had nothing to do with how smart they were. They were bright in the way they captured the light of the sun and seemed to double it before giving it back to the world.

The shape watched, along with Gustav Gloom, as the littler of the two girls carried her box of books into the new house.

“Those are scary books,” the shape said. “I can tell from here. And from the way they all smell like her, that little girl must have read some of them half a dozen times. She likes spooky things, that one. A girl like that, who enjoys being scared, she’s not going to be kept away from a house like this, no matter how stern the warning. I wager she’ll be over here for a visit and making friends with you before that cat of hers takes its first stop at its litter pan.”

Gustav gave the black shape a nod; as always, he offered no smile, but the sense of a smile, the easy affection that comes only after years of trust.

“Why not hope for the best, just this once?” the shape asked. “Why can’t you believe me when I say that she’ll be over here saying hello before the day is out?”

Gustav looked away from the view on the other side of the gate and gave one of his most serious looks to the black shape beside him: the shape of a man so tall and so skinny that his legs looked like sticks, with knees and elbows that bulged like marbles beneath the shape (but not color) of a pin-striped, powder-blue suit.

It was not Mr. Notes, who plays no further role in this story, and who we can safely assume continued to live in the home for nervous people and use up little boxes of black crayons for the rest of his days.

It had the outline of Mr. Notes and the manner of Mr. Notes and even the voice of Mr. Notes, except that it didn’t sound like it was breathing through its nose like Mr. Notes did, and its words didn’t come with that little extra added tone that Mr. Notes had used to give the impression that everything around him smelled bad.

It was the part of Mr. Notes that had stayed behind when Mr. Notes ran screaming from the Gloom house, a part that he would not have wanted to leave behind, but a part that had not liked Mr. Notes very much and had therefore abandoned him, anyway.

Its decision to remain behind was the main reason the real Mr. Notes now had to live in a padded room.

“Don’t worry,” the shadow of Mr. Notes said. “You’ll be friends soon enough.”

Gustav thought about the girls, who seemed to have been born to live in sunlight, and for just a second or two, he became exactly what he’d always seemed to be to all the neighbors on Sunnyside Terrace: the saddest little boy in the world.

“I have to warn her,” he said.

Gustav Gloom and the People Taker © Adam-Troy Castro 2012