Ritter grapples with a cunning adversary in this new Mongolian Wizard story, presented in celebration of the 50th World Fantasy Convention’s Toastmaster, Michael Swanwick . . .

Five days before the battle for Paris, Ritter found himself in a meadow, under a clear blue sky, enjoying a picnic lunch with Lady Angélique de La Fontaine. How she had managed this, he did not know. But her aristocratic connections, combined with her military rank as a psychic surgeon, had conjured up a wicker basket filled with cold chicken, ripe brie, white grapes, a crusty baguette, a bottle of Crémant d’Alsace, tinned goose liver pâté, and a handful of ginger snaps wrapped up in a linen napkin. Also, and even more surprisingly, she had arranged a daylong leave of absence for a Prussian officer on indefinite assignment to British Intelligence.

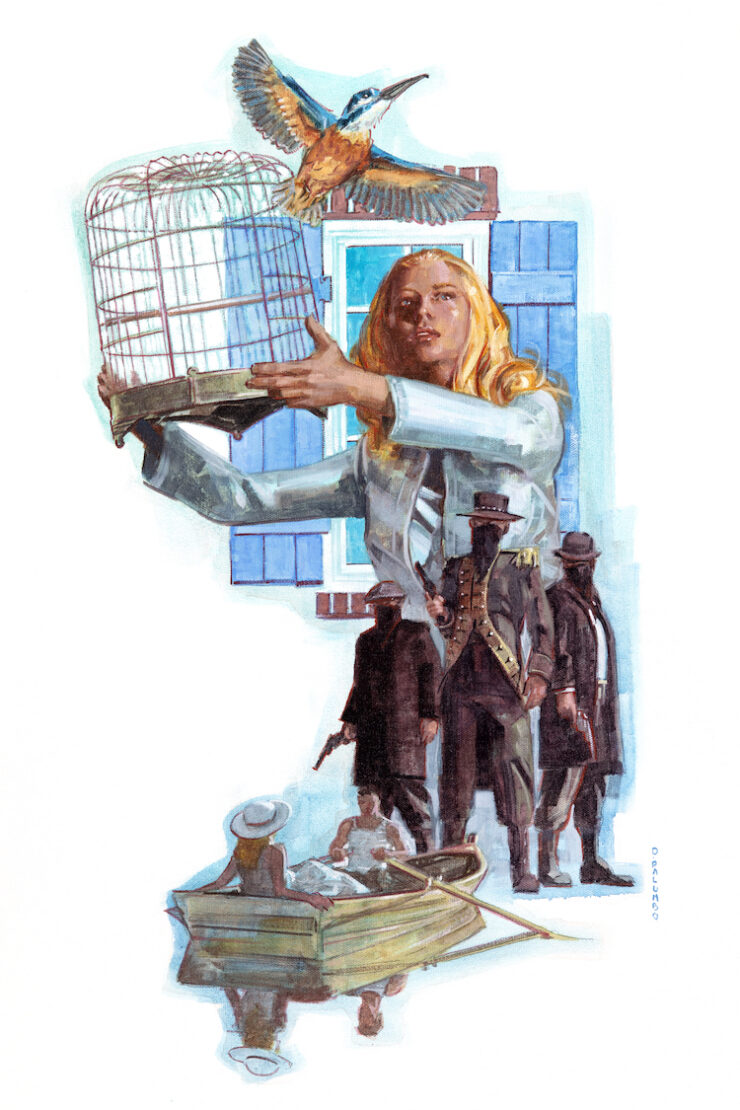

As they ate, they chatted about art, books, the peccadillos of mutual acquaintances—anything and everything but the war. At one point Ritter gestured at the wicker cage they had brought along with the blanket and basket of foodstuffs. “This bird—a kingfisher, by the look of him—is a charming fellow. But why is he here with us?”

“She,” Angélique said. “This is no kingfisher but a halcyon. She lays her eggs on a floating nest upon the sea. To protect them, she has power over the winds. So long as little Halçi is with us, the weather will be clement.”

A pleasant while later, when they had fallen into a companionable silence, Angélique dabbed away a crumb from the corner of Ritter’s mouth and, rising gracefully to her feet, said, “We’d best go indoors now. It looks like it’s going to rain.”

Ritter looked at the small cottage at the edge of the meadow and then at the halcyon in its wicker house. “Rain? But you said—”

Putting her hands on her hips, Angélique scowled most fetchingly down at him. “Kapitänleutnant Franz-Karl Ritter, you are, if I may say so, one damnably difficult man to seduce!”

Hearing it put that way, Ritter naturally concluded that he had no choice but to go wherever she wished and do whatever she desired.

Afterward, they lay naked upon a surprisingly large and comfortable bed, while Angélique queried Ritter about the history of every bullet scratch and saber scar on his body. With her fingertips, she traced an ugly discoloration on his forearm. “And this?”

Ritter laughed. “I fell out of a tree when I was a boy. It was the first time I had ever been seriously hurt and with the bone sticking out of my arm and blood everywhere, I was of course terrified. I hobbled home in tears, clutching one arm in the other, and when I got there, my father slapped me to stop my crying.”

“How horrible!”

“It was not horrible at all. It worked. While he set the bone and bandaged me up and dosed me with laudanum, my father explained the standards of behavior expected from one of our class. I went to sleep that night feeling very proud of the man I was meant to be.”

“Yes, but still—”

Ritter yawned. “Please forgive me,” he said. A warm breeze fluttered the lace curtains in the windows and the sunlight pouring through them was as golden as honey. Bees hummed comfortably in the clover outside. “I’m a little drowsy.”

“That is nothing to apologize for,” Lady Angélique said. “Here, place your head in my lap. If you wish to nap, do so.”

Looking up through her hair, which she had let fall to enclose both their heads in a cascade of gold, Ritter felt a moment of perfect contentment. “What was it Goethe wrote?” He yawned again. “Verweile doch, du bist so schön. Linger awhile, you are so beautiful. I could live in this moment forever.”

“My silver-tongued scoundrel.” Angélique’s smile fluttered and faded in Rittter’s vision. His eyes closed and he drifted off to sleep.

A fist pounded and a voice muffled by the thickness of the door cried, “Commandant Ritter! Vous êtes—”

“—ordered to report to Command. My leave is canceled. Why else would a messenger be sent me?” Ritter grumbled as he struggled to his feet. Raising his voice: “All right! Jawohl! D’accord!” He threw on his uniform, commenting less to Angélique than to himself, “I speak so many languages these days I hardly know which one to think in.”

A hasty kiss and Ritter was at the door. He flung it open.

There was no one there.

Jeering in a way absolutely incompatible with the woman he was coming to know, Lady Angélique said, “Made you look!”

Then, without any transition, they were sitting—clothed, and fashionably so—at a small table on a terrace overlooking the Seine.

Before the war, this café had been one of Ritter’s favorite places in Paris. With the current shortages, he was certain it did not look this pleasant anymore. But the illusion was perfect, down to the hot metal aroma that came from the espresso machines, mingled with the smell of coffee brewing.

Lady Angélique raised a crystal goblet. “Santé!” She drank.

Ritter neither touched his glass nor responded to the toast. “Obviously,” he said, “I’m still asleep. Who are you and what are you doing in my dreams?”

The false Angélique pouted. A drop of wine, red as blood, lingered on her lower lip. “You are no gentleman, sir. You find yourself in a romantic situation with—I shall employ no false modesty—a devastatingly beautiful woman. Even in a dream, you should be smitten.”

“As for your appearance, it is stolen from a woman I sincerely admire. On you it looks grotesque. As for my behavior, I am a gentleman by birth and nothing can alter that. I am also a soldier by profession. You are clearly an enemy operative whom I am honor-bound to oppose, whether I am awake or asleep. Answer my question.”

The lady sighed and put down her glass. “Very well.”

White clouds drifted slowly across the glassy surface of a sky-blue lake fringed with water lilies. Ritter recognized the lake as one belonging to the estate of his late uncle near Venusberg. He had spent many pleasant hours there in his youth.

They were on a rowboat and Ritter was working the oars. The woman sitting opposite him had luxuriant red hair that fell over her shoulders in artful curls. She was dressed in white and carried a silk parasol to protect her skin from the sun. Her face was beautiful in a way totally unlike Angélique’s. “I am Hélène, Baroness D’Alcyone. But you, my sweet, may call me Leni, if you wish.”

Leni was the German diminutive of Hélène. “You are not French, then?” Ritter said.

“I am Alsatian by birth. The title is my husband’s.”

Ritter was wearing canvas shoes, light duck trousers, and a sleeveless rowing shirt. He noticed that Hélène’s eyes did not meet his. She was watching the actions of his muscles as he labored. “And your purpose?”

“I should think it obvious.” Hélène leaned forward. Had her décolletage previously been so low? “I desire an intimate, passionate relationship with you.”

“I seem to be quite the lady’s man today,” Ritter said dryly.

Hélène leaned back. “I beg your pardon?”

“Never mind. Your plan, I take it, is to begin an imaginary affair with me that will continue until I have become addicted to your beauty and your amorous skills. Then you will withhold your ghostly favors until I agree to betray Sir Toby by sharing his secrets with your handlers.”

“It sounds so tawdry put that way. But, yes, something like that.”

“Does your husband know of your…profession?”

The baroness’s laughter was like silver bells. “Goodness, no! Oh, dear Andre knows that I serve the Mongolian Wizard, as any dream-walker must. But he thinks me a spy.”

“Isn’t that what you are?”

“No, silly. I’m a succubus.”

“A succubus is a courtesan of the imagination,” Hélène said. They were strolling through what Ritter at first assumed, from its opulence, to be the vulgar palace of a nouveau-peerage upstart. Then the preponderance of red velvet curtains and smoky, gold-flecked mirrors combined with the poor quality of the statuary and the smell of stale cigars revealed it to be a brothel. They passed by an open doorway and the activities within were such as would be expected in such a place. “It is a rare skill to be able to create a physically convincing illusion of intercourse within somebody’s mind. But I can do more than that. You wish to make love atop the Jungfrau? Or beneath the sea? The snow will be warm, the water breathable. Your every night will be a delightful respite from the war.”

“Is there a point to this?” Ritter asked.

They passed by more open doorways. The baroness squeezed Ritter’s arm. “You are not looking,” she said. “You should. I assure you that you will see nothing that I would not willingly and enthusiastically do with you. Unleash your inner voyeur. He might pick up a few ideas.”

“I really don’t think this is a productive use of either your time or mine.”

Hélène cocked her head, as if listening to otherworldly voices. Then she said, “Why not? In dreams there are no consequences. The beds are like clouds and the nights never end. Why not take advantage of them?”

“It is a matter of morality.”

Again, that elfin laughter. “Oh, la! What a liar you are. Where do you think this brothel came from? It is constructed from your memories. I assure you, I have never visited such an establishment.”

It was a hit and it stung. But Ritter forced back his embarrassment. “I am not proud of having done so. But I always tipped more than was expected and never required any of the ladies to perform acts they found distasteful.” He did not add that most of these visits had occurred at times of great loneliness—it would have sounded like an apology.

“If this part of your history offends you, then tell me something of which you are proud.”

Ritter considered. “Very well. I was once robbed by highwaymen. I was in a coach that was stopped by three brigands and, upon their captain’s command, the coachman and all the passengers alit. The men were well-armed and the other passengers were respectable citizens who had no notion of putting up a fight, so I had no option but to surrender my valuables. I burned with humiliation, though, for I was a newly commissioned officer and thought the incident was a smear upon my honor.” Ritter smiled at the memory. “I was very young.”

“So thrilling! Were you bold and gallant?”

“No, I was methodical and observant. The highwaymen wore kerchiefs over their lower faces to disguise themselves and hats pulled low to obscure their eyes. But they could not disguise their heights, their stances, the sound of their voices. Also, I noted that their horses were old and spavined, and this told me what class of people they were.

“Their captain saw me looking about and asked why.

“‘So I can give accurate testimony at your trial,’ I replied.

“At that, his two underlings threw me down in the dirt at their captain’s feet. His boots had distinctive silver buckles far better than anything else he wore. Doubtless they were part of the loot from an earlier robbery.

“I heard the sound of a pistol being cocked. ‘I doubt this will ever come to court,’ the captain said, and fired. I felt a blinding pain in the side of my skull. Then the fellow roared with laughter and, joking with one another, the highwaymen climbed on their horses and departed.

“The coachman and a lawyer from Hamburg helped me to my feet. By slow degrees, they made me realize that, as a joke, the highwayman had fired into the air while simultaneously kicking me in the head.

“I swore to myself that he would pay for that.

“Men can travel only so far at night, and thieves will necessarily want a nearby bolt-hole in case of pursuit. So I made my way to the nearest village the next evening, dressed in clothes borrowed from my ostler. There were only two taverns in the village and one was so quiet I did not bother going in. But, standing in the doorway of the other, I saw three revelers who, by their heights, their stances, and their voices, were my prey, buying drinks for all their friends. One wore boots with silver buckles. I turned away, lest they see my bandaged face and suspect who I was, and joined a table of glum-looking men who had been excluded from the festivities. A single round of beer and a sympathetic ear bought me the identities of all three and where they lived.

“The next day, four soldiers and I returned with warrants for the highwaymen, beginning with the captain, who was the only one I cared about. He lived in one of those rural buildings that are half farmhouse and half barn. Alas for him, on seeing us, he seized a rapier from a peg by the door and came roaring out, swinging wildly. The soldiers scattered, because no man is more dangerous with a sword than he who has no idea what he is doing. But I stood my ground and, leveling my pistol, shot him right in the center of his chest. That was the first time I killed a man.”

“Oh, my! You must have felt terrible afterward.”

“I felt nothing but pride in my cool-headedness.”

Hélène cocked her head again. Then she said, “That was an ugly story. Why did you tell me it?”

“To let you know that all the time you are toying with me, I am observing you, and that it is dangerous to let me learn too much. Don’t you think it is time that I woke up?”

“Oh, you can’t do that. Not until I’ve had my wicked way with you.”

“That will never happen.”

A third cock of her head, and then a flirtatious smile. “Never is a long time. A great deal can happen before it is over.”

Now they were in Sir Toby’s office. It smelled of leather and old paper and expensive tobacco. There was a dagger mounted on the wall and a stuffed owl atop the bookcase. “Tell me something,” Ritter said, before the succubus could develop an unhealthy interest in her surroundings.

Hélène shoved a mound of documents off the desk and perched upon its edge. “Anything!”

“Who am I?”

With a mocking lift of one eyebrow Hélène said. “Don’t you know?”

“You haven’t once addressed me by name. Nor have you made any references to my likes, dislikes, or personal history. I mentioned my superior’s name and you did not react to it, which would be strange indeed if you had any idea who he was. So you are squandering your rare talent on someone who is to you a random stranger. It makes no sense. It beggars all logic. It makes me wonder exactly what your game is.”

“What a prig you are!” Hélène’s eyes flashed. “And a pill. You are a prig and a pill. How dare you treat me so rudely? You forget, sir, that I am a baroness.”

Ritter, who had been holding it back, now channeled his own anger into speech. “You are no lady, much less a baroness. Your every word and action betray your origins in the lower classes. You hold a wineglass not by the stem, as a lady would, but by the bowl. And, by the way, do not imagine that a sidewalk café serves wine in crystal—the breakage would be ruinous. When I was rowing, your glance went where no properly reared woman would allow a man to see it going. Your accent is good, which means you have been schooled for your role. Yet when you speak as a lady you sound scripted, when you speak like a demimondaine you are unconvincing, and when you speak naturally you revert to schoolgirl diction—from ‘Made you look!’ to ‘a prig and a pill.’ Meanwhile, your dream leaps from locale to locale, as if they were so many painted backdrops in a comic opera. Finally, there is the ridiculous coincidence of the name D’Alcyone with the halcyon bird. Tell me, exactly how old are you?”

In a tiny voice, Hélène said, “Twenty-one.”

“The fact that you think that is a worldly age tells me you are much younger. Sixteen perhaps?”

Indignantly, Hélène said, “I’m eighteen! Last month.”

Out of nowhere, a voice said, “All right. This can stop now.”

“Yes, Maître,” Hélène said.

“What?”

A woman half-materialized in the chair behind Sir Toby’s desk. She was heavyset, plainly dressed, and bore an air of authority. “What have you learned from today’s session?”

Eyes downcast, Hélène said, “That…some men are immune to desire?”

“Who the blazes are you?” Ritter demanded of the ghostly newcomer, still too angry to be polite.

“I am the one charged with, as you said, schooling this wayward waif.” To Hélène, the Maître said, “Put together the clues: This man’s anger when you assumed the appearance of what should have been his purely theoretical idea of perfect beauty. His reference to that woman as someone he sincerely admires. Saying that you look grotesque in her form. Refusing to so much as glance at the activities in the maison de tolérance, though they were based on his own experiences. His constant and excessive coldness in the face of your generous offers.”

“I…”

“Idiot child. You never had a chance with him. The fool is in love.”

“Ohhhh.” Hélène clapped her hands in delight. “I was afraid the fault was mine.”

“Hellfire and brimstone!” Ritter exclaimed. “What is all this about?”

“Shall I tell him?” Hélène asked. “It is most satisfying to tell a man to his face that he has been used.”

The Maître nodded and Hélène said, “A succubus is not simply sent out into the dreams of powerful men. She has to be trained in the social graces first. You have been quite helpful in that regard—particularly the tip about how to hold a wineglass. I thank you for that.

“Oh, and I was never going to roll in the sheets with you, dream or not.” Hélène blew Ritter a kiss. “So your virtue is safe and you may wake up now.”

When Ritter was done telling Lady Angélique a lightly censored version of his dream—omitting the brothel and Hélène’s assuming her appearance—she turned to the birdcage and said, “But how does Halçi fit into this escapade?”

“Normally, a dream-walker has to be physically close to her subject to enter his dreams. But if she establishes an empathy with an animal, even so slight a one as a halcyon, it can be used as a kind of amplifier. I can reach into Freki’s thoughts from miles away. Where did you acquire that bird?”

“From a funny little shop in the rue de Beaune. She was not easy to buy. The shopkeeper told me she would only sell Halçi to someone of quality.”

“She wanted someone of the upper classes for her protégé to practice on. You mentioned a picnic, and she reasoned you would be accompanied by a man of some social standing. Was the woman stout? Of a certain age? Imposing?”

“That does seem to describe her.”

“Then she will be long gone by the time we can notify the authorities to arrest her.”

Unhurriedly, Lady Angélique donned her dress. Then, lifting the birdcage, she opened the back door of the cottage, which faced onto the forest.

“What are you doing?” Ritter asked. Following Angélique’s lead, he had begun to get dressed, though more slowly, for he was covertly watching her body disappear from view.

“Halçi is an innocent girl and the world is a wicked place. I am setting her free so she cannot be used to ensnare other men in the poor girl’s education.” Angélique opened the cage door. In an instant, the bird perched there. Then she was gone.

Almost, Ritter said that it would make little difference in the succubus’s training. But, staring up at the side of Angélique’s face as she in turn gazed after her vanished halcyon, he realized in a flash that the Maître had been right. That he was completely, absolutely, in love with her. On the instant, he determined to tell her so, and damn the consequences. “Angélique, I just now realized something. I—”

A fist hammered on the door. “Kapitänleutnant Ritter!” The voice was male, impersonal, military. “Again?” Ritter groaned. “I am coming!” he shouted, to silence his summoner. To Angélique he said, “I must go.”

“I know.”

“I don’t want to.”

“I know that too.”

As he was fastening his belt and pulling up his boots, Ritter called Freki in from the fields. Then he went outside where a soldier gave him the expected orders to return to duty. He and the wolf followed the messenger down the road, away from the picnic meadow. Glancing over his shoulder, he saw Lady Angélique standing in the doorway, her face a pale, sad oval.

Then Ritter turned his gaze forward, toward the future.

He was back in the war again.

“Halcyon Afternoon” copyright © 2024 by Michael Swanwick

Art copyright © 2024 by Dave Palumbo

Buy the Book

Halcyon Afternoon