Harrison Harrison—H2 to his mom—is a lonely teenager who’s been terrified of the water ever since he was a toddler in California, when a huge sea creature capsized their boat, and his father vanished. One of the “sensitives” who are attuned to the supernatural world, Harrison and his mother have just moved to the worst possible place for a boy like him: Dunnsmouth, a Lovecraftian town perched on rocks above the Atlantic, where strange things go on by night, monsters lurk under the waves, and creepy teachers run the local high school.

On Harrison’s first day at school, his mother, a marine biologist, disappears at sea. Harrison must attempt to solve the mystery of her accident, which puts him in conflict with a strange church, a knife-wielding killer, and the Deep Ones, fish-human hybrids that live in the bay. It will take all his resources—and an unusual host of allies—to defeat the danger and find his mother.

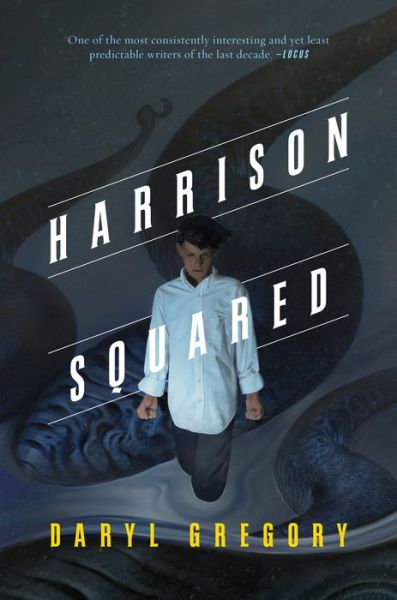

Daryl Gregory’s Harrison Squared is a thrilling and colorful Lovecraftian adventure of a teenage boy searching for his mother, and the macabre creatures he encounters—available March 24th from Tor Books!

1

The building seemed to be watching me.

I stood on the sidewalk, gazing up at it. It looked like a single gigantic block of dark stone, its surface wet and streaked with veins of white salt, as if it had just risen whole from the ocean depths. The huge front doors were recessed into the stone like a wailing mouth. Above, arched windows glared down.

The sign out front declared it to be The Dunnsmouth Secondary School.

This was like no school I’d ever seen before. I didn’t know what it was—a mausoleum, maybe? Something they should have torn down. Yet some lunatic had looked at this hulk and said, I know, let’s put kids in here!

Except the kids were nowhere to be seen. Nobody was outside, and the windows were dark. I’d suspected that I’d made a mistake coming with my mom to this town, but I now realized that I was wrong: I’d made a horrible mistake.

The truck door slammed behind me. Mom hustled around the back of the vehicle. In the bed of the truck were “the buoys in the band”: four research buoys labeled e, h, s, and p, otherwise known as Edgar, Howard, Steve, and Pete. The devices, which looked like red-and-white flying saucers with three-foot-high towers attached, were the reason we’d driven across the country.

“Hmm,” Mom said, looking up at the building. “It is kind of… tomb-y.” She touched the back of my neck. From inside the building came the sound of distant murmuring, or perhaps a chant. Maybe they were saying the pledge of allegiance. Or the pledge of something.

“It’s not too late, H2.” That was her nickname for me: Harrison Harrison = Harrison Squared = H2. It was the kind of humor that scientists found hilarious. “I can call your grandfather tonight. We can put you on a plane—”

“It’s fine,” I said, lying through my teeth. “I’m fine.” It had been my decision to come to Massachusetts with her on this research trip. I’d insisted. She wasn’t going to dump me in Oregon with my grandfather. It was only going to be a month, two months tops, before I got back to my regularly scheduled life. Besides, I couldn’t see Mom doing this research trip alone. She’d probably get so obsessed she’d forget to feed herself.

So we’d crossed the continent, four days from ocean to ocean, pushing the pickup as fast as it could go, and rattled into town so late last night that not a streetlight was burning. We’d lost all bars on our phones, and the GPS apps had stopped working, so it was almost by accident that we found the clapboard house Mom had rented, sight unseen, over the phone.

It had looked dismal in the dark, and morning hadn’t improved it—or the town. We’d awoken (late!) to find ourselves surrounded by mist, fog, and cold. The Heart of Bleakness. I don’t think Mom had noticed; she’d been focused on readying the buoys for deployment. Each tower supported a signal light, a satellite dish the size of a medium pizza, and a solar panel; and each of these components had to be wired to the batteries in the base. That had taken us longer than we’d thought it would. Then we’d loaded them into the truck and driven back up Main Street to the school.

Mom glanced at her watch. She’d chartered a boat to take her out, and she was supposed to have met the captain at the pier fifteen minutes ago.

“It’s okay,” I said. I slung my backpack onto my shoulder. “I’ll check myself in. You’ve got a boat to catch.”

“Don’t be ridiculous,” she said. “I’m still your mother.”

Together we pushed on the big wooden doors, and they swung open on squealing hinges. The large room beyond was a kind of atrium, the high ceiling supported with buttresses like the ribs of a huge animal. Light glowed from globes of yellow glass that hung down out of the dark on thick cables. The stone floor was so dark it seemed to absorb the light.

Corridors ran off in three directions. Mom marched straight ahead. There were no sounds except for the slap of our feet against the stone. Even the chanting had stopped. It was suddenly the quietest school I’d ever been in. And the coldest. The air seemed wetter and more frigid inside than out.

I noticed something on the floor, and stopped. It was a faded, scuffed logo of a thin shark with a tail as long as its body, flexing as if it were leaping out of the water. Below it were the words Go Threshers.

My first picture books had been of sharks, whales, and squids. Mom’s bedtime stories were all about the hunting habits of sea predators. Threshers were large sharks who could stun prey with their tails. As far as I knew, no one in the history of the world had ever used one as a school mascot.

Mom stopped at a door and waved for me to catch up. Stenciled on the frosted glass was Office of the Principal. From inside came a slapping noise, a whap! whap! that sounded at irregular intervals.

We went inside. The office was dimly lit, with yellow paint that tried and failed to cheer up the stone walls. Two large bulletin boards were crammed with tattered notices and bits of paper that looked like they hadn’t been changed in years. At one end of the room was a large desk, and behind that sat a woman wearing a pile of platinum hair.

No, not sitting—standing. She was not only short, but nearly spherical. Her fat arms, almost as thick as they were long, thrashed in the air. She held a fly swatter in each hand and seemed to be doing battle with a swarm of invisible insects. Her gold hoop earrings swung in counterpoint.

“Shut the door!” she yelled without looking at us. “You’re letting them in!” Then thwack! She brought a swatter down on the desk. Her nameplate said Miss Pearl, School Secretary.

“Excuse me,” Mom said. “We’re looking for Principal—”

“Ha!” Miss Pearl slapped her own arm. Her platinum hair shifted an inch out of kilter. She blew at the pink waffle print on her arm, then sat down in satisfaction. I still could not see any bugs. The air smelled of thick floral perfume.

She looked up at us. “Who are you?”

“I’m Rosa Harrison,” Mom said. “This is my son, Harrison.”

“And his first name?” She stared at me with tiny black eyes under fanlike eyelashes.

“Harrison,” I said. Sometimes—like now, for example—I regretted that my father’s family had decided that generations of boys would have that double name. Technically, I was Harrison Harrison the Fifth. H2x5. But that was more information than I ever wanted to explain.

“He’s a new student,” Mom explained.

“Oh, I can see that.”

“Principal Montooth is expecting him.”

“Now?” Miss Pearl said. “It’s already fourth period.”

“We’re running late.”

“Did you bring his transcripts?” Miss Pearl asked. “Test scores? Medical records? Proof of residency?”

“No, we just—”

“Not even proof of citizenship?”

Uh-oh.

Mom is Terena, one of the indigenous peoples of Brazil. Which means that her people—my people—were nearly wiped out in A.D. 1500 by Europeans who looked a lot like Dad. He was Presbyterian white (like “eggshell” and “ivory,” “Presbyterian” is a particular shade of pale). I’m a Photoshopped version somewhere between the two, with Dad’s blue eyes but skin a lot darker than your typical hospital waiting room. You grow up in southern California looking like me, a lot of people assume you’re Mexican. Some of those people assume you’re undocumented, and let their biases spool out from there. Mom got annoyed when people said racist stuff about her, but when somebody started talking stupid about me, her only begotten?

Jaguar claws, my friend.

Mom leaned over the desk. “Does he look like he doesn’t belong here?”

Miss Pearl blinked up at her, finally found her voice. “It’s standard,” she said.

“Look, Miss… Pearl, is it?” Classic Mom. “I’m in a bit of a rush. Let’s take care of the paperwork later and get my son into class.”

It was then I realized that she’d forgotten all the forms I’d filled out back in San Diego. When she was deep into a research project—which was pretty much all the time—she was prone to falling into Absent-Minded Professor mode. When Mom was AMPing, mundane details fell through the cracks.

Miss Pearl was confused. “Are you telling me you don’t have any documentation for this child whatsoever?” The cloud of perfume surrounding the woman seemed to expand. My nose itched madly.

“Of course I have documentation,” Mom said. “Just not with me. If you could just give us some sort of class schedule, we can—”

I sneezed, and Miss Pearl glared at me. “He’s what, fifteen years old?”

“I’m sixteen,” I said. “A junior.”

Miss Pearl sighed. “Why don’t you start in Mrs. Velloc’s class, then. Practical skills. Room 212.”

“Thank you,” Mom said. It was the “thank you” of a sheriff putting the gun back in the holster after the desperados had decided to move along. Miss Pearl, however, had already returned to fly-swatting. “Close the door behind you!” she called.

Out in the hallway, Mom looked left, then right. She seemed to have already forgotten Miss Pearl. She was like that: Her mind moved fast, and she didn’t let anger fester.

“Two-twelve,” she said, and glanced at her watch.

“Just go, Mom,” I said. “I can find it.”

She heard something in my voice and looked up into my eyes. About a year ago I’d passed her in height.

“You’re mad,” she said. She was worried.

I didn’t let things go as quick as she did. And when I was little, I was the King of All Tantrums. Do you know how wild you have to be to be kicked out of elementary school? The answer is: very.

“A little bit,” I said.

“Is it about this school?”

“I thought you were taking care of the forms.”

“Paperwork is for small minds,” she said. But she was smiling as she said it.

“Okay, okay,” I said. “I’ll take care of it tomorrow.”

“Your mind’s too big for paperwork too,” she said. “How’s the leg?”

First the question about being mad, and now the leg. She hardly ever asked about it. When I was little she’d checked in with me all the time, making sure the socket was fitting, and that my skin was okay. But she’d stopped the constant questioning when I became a teenager. I hadn’t told her that the leg had started acting up last night. It wasn’t socket pain; it was a weird coldness in my phantom limb. I’d chalked it up to the long trip and hadn’t mentioned it to her. Had she noticed me limping?

“You’re being parental,” I said. “Go find that squid.”

My mom specialized in finding big things swimming in places they didn’t belong. She’d studied whale sharks, sperm whales—the biggest of the toothed whales—and all varieties of squids. Her latest obsession was Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni, the colossal squid. Forty-five feet long, with the largest eyes in the animal kingdom, whose suckers are ringed not only by teeth but sharp, swiveling hooks. It’s never supposed to come north of Brazil—but she was sure it did, based on, among other evidence, the beaks found in the guts of certain whales. Down in the abyss it’s a dog-eat-dog world, where some of the dogs are the size of city buses.

“Fique com Deus, querido,” she said, and kissed me on the cheek. “Até depois.”

She ran for the exit. She didn’t run in that straight-backed, floor-skimming, not-really-running way adults did—she ran like a kid, all out. She hit the big doors and escaped into daylight.

Science Mom flying off to her next adventure.

. . . while I was left with this: a dark hallway in a school that didn’t want me here.

The doors nearest the office were all in the 100s. The doors were all closed, though from some of them I heard voices. Then I found the stairs and went up.

On the landing was a huge aquarium, eight feet long and five feet high. The water inside was green and silt-filled. Something moved within it, but I couldn’t make it out. Maybe it was a thresher, and they kept their mascot on the premises.

I reached the second floor to find another row of closed doors. The light seemed even dimmer than downstairs. I bent to look at the number plate next to a door and was relieved to find that at least now I was in the ballpark: 209, 210…

Room 212. I put my hand on the doorknob—and then it swung open, pushed from the inside. A very tall white woman in a very long black dress looked down at me. She seemed to be constructed of nothing but straight edges and hard angles, like the prow of an icebreaker ship. Her black hair, shot with gray, was pulled back tight against her head. Her nose was sharp as a hatchet, her fingers like a clutch of knives.

“Mr. Harrison,” she said. “I am Mrs. Velloc.” Her lips barely moved.

Behind her, kids my age sat in four rows. Lengths of rope were draped from one desk to another, and the students were tying them together. Or had been, until they’d all stopped to look at me.

They all seemed to be related to each other. Black hair, pale skin, dark eyes. Every one of them Caucasian. I fought the urge to back away.

I said, “The woman in the office—”

“Miss Pearl.”

“Right. She told me to come here.”

“And you followed directions. Perhaps you’d like a commendation.”

Mrs. Velloc made a small gesture, and I found myself walking into the room.

“Class,” she said. “This is Harrison. He is from California.”

She enunciated the word carefully, as if it were an exotic country. I wondered how she knew where I was from. Had Miss Pearl buzzed her while I was on my way up?

“Hello, Harrison,” the students said in unison. Not just generally at the same time, but in perfect synchrony, like a choir. A choir that had been rehearsing.

I lifted a hand in greeting. They stared at me. They were dressed in blacks and grays, not quite a uniform, but definitely a look, as if they all did their shopping at clinicaldepression.com. My tie-dye shirt was like a loud laugh at a funeral.

I let my hand drop.

“It’s Practical Skills hour,” Mrs. Velloc said. “We’re learning how to make a proper net. Do you know your knots, or do you not?”

“Pardon?”

She already seemed put out with me. “This way.” She led me to an empty seat in the first row. On the desk was a flat stick almost two feet long with notches at each end. Its middle was wound with rope.

“Lydia will show you the sheet bend. Miss Palwick?”

The girl to my right—Lydia Palwick, I presumed, since I’m smart like that—looked at me with a slightly surprised expression, though that was probably because her eyes were so large. Her long black hair shined as if oiled.

Mrs. Velloc turned and walked back to her desk. She picked up a tiny book and began to read to herself.

I looked down at the section of rope that lay across my desk. Then I picked up the tail end of the rope that was spooled around the big stick. Okay, I thought. Tie this thing to that thing and make a net. No problem.

Except I didn’t know any sailor knots. Mom did; she was great at that stuff. But I never went on boats. I didn’t know anything about nets or ropes or sheet bends.

Lydia watched me fumble around, then took the stick out of my hands. She moved it in and out of the net, over and around, the rope spooling behind it. Suddenly there was a new diamond in the net.

“Wait, how did you—?”

“Left, loop, right, loop, over, and through,” she said. Her voice was flat, bored.

I leaned closer to her and whispered, “Can I ask you a question?”

She glanced to the side but didn’t pull away from me. I said, “How much of Practical Skills hour is left?”

Forty minutes later the class showed no sign of ending, and my fingers prickled from what felt like microscopic needles. I didn’t know that rope could get under your skin like that. Also? I was bored bored bored. My phone was getting zero reception, so there was no one I could text to back home, and no one here was passing notes or even whispering. They simply worked, fingers busy as spiders.

I finally leaned over to Lydia and whispered, “Why is everybody so quiet?”

She frowned. “Why are you always talking?”

“I’ve said like five words since I got here.”

Mrs. Velloc’s head whipped around at the noise. I shut up. A few seconds later, Lydia whispered, “Chatterbox.”

Somewhere far away, a gong sounded. The students stood as one, and then packed the piles of rope into large wooden trunks lined up at the back of the room. I’d managed to connect three or four lengths of rope. In the same amount of time, Lydia had created a net the size of a queen-sized blanket.

The students began to file out of the room. I walked to Mrs. Velloc’s desk. Eventually she looked up from her book.

“I don’t know where to go next,” I said. “They didn’t give me a schedule.”

She looked at me as if I were a moron. “Follow Lydia,” she said.

“To where? The office? Because I can—”

“Do what she does. Go where she goes. Your schedule is her schedule.”

I glanced toward the door. Lydia had already left the room.

“Is that too complicated for you, Mr. Harrison?”

I didn’t know where my temper came from. Mom didn’t suffer fools gladly, but her anger never lasted longer than a minute. My dad supposedly never hurt a fly. But me… Calm did not come naturally. Sometimes—like, say, when somebody treats me like I’m an idiot—I could clearly picture my hands around their neck. I could almost feel myself squeezing.

When I was little I didn’t know what to do with all that emotion, and I actually did try to strangle people. I punched other kids. Bit teachers. Screamed at, well, everybody, but mostly my mother. Gradually I learned to control myself. My main technique, and still my go-to move when I was feeling the rush, was to simply observe myself. Catalog what was going on in my body and my head. Hey there, look at that fist clenching! Feel that heart beating! Take a gander at that violent movie playing in your head—got any film music to go with that?

I didn’t actually step out of my body. I wasn’t that crazy. But watching myself did get me to settle down. Rage makes little sense from the outside.

I relaxed my hand and smiled at Mrs. Velloc. “I think I got it,” I said.

I walked out, and my right leg was throbbing, right down to my invisible toes. I made sure not to limp.

Students streamed out of the rooms, but it was an orderly stream, without pushing or shoving. Nobody yelled or even raised their voice. Most of them looked younger than me, but they all had that same dark-haired, pale, fishy look as the kids in Velloc’s class. From behind I had no idea which one was Lydia, but I finally spotted her as the streams converged on the stairway down.

“Hey, Lydia!”

Scores of faces turned to look at me. The flow of traffic stuttered, then resumed.

Lydia looked up at me. Then she closed her eyes and slowly opened them again, as if hoping she’d imagined me. Nope. Still here. She backed out of the line of students and waited for me on the first landing with her back to the aquarium.

“Thanks,” I said when I reached her. “Velloc says I should shadow you until they give me a schedule.”

“Shadow me,” she said skeptically.

“It’s not my idea,” I said. And suddenly it seemed like a very stupid idea. “Listen, never mind, I’ll figure this out.”

“I doubt that,” she said. “Lunch is this way.”

She led me downstairs and along a corridor to a cavernous room. The cafeteria. The serving line was on one side, and wooden tables filled the rest of the space. I followed Lydia’s lead and picked up a large wooden bowl and tin cup. One by one the students passed the counter, where a pair of lunch ladies filled the bowls with a steaming, chunky stew. The air smelled of vinegar.

I held out my bowl. The lunch lady, a thick-necked woman with horsey teeth, held out her ladle. When she moved I caught a glimpse of the kitchen behind her. A woman who could have been her older sister stood at a metal table wearing a bloody smock. She held a huge silver fish, perhaps three feet long, by its tail. The creature twitched weakly in her grasp. Suddenly she plunged a knife into the belly of the fish and ripped down.

I dropped my bowl.

The serving lady, still holding her ladle aloft, scowled at me over glasses that perched at the end of her long nose.

I raised my hands. “That’s it. I’m done.”

Lydia frowned at me.

I turned toward the door. Lydia said, “Where are you going?”

“Home,” I said.

She followed me for a moment, then grabbed my arm. Her eyes were sea green.

“Truancy is a crime,” she said.

“Then I guess I’m a criminal. Besides, who uses the word ‘truancy’?”

Something changed in her face. I’d just become marginally more interesting to her.

“See you around, Lydia. It was a pleasure meeting you.”

2

Lydia didn’t try to stop me again. I walked fast for the door, feeling the eyes of the students on my back, but I didn’t care. I was going home. Not to the rental house down the street—all the way back to California, to my friends. My real school. In San Diego, the school hallways were outdoors. The sun shined all the time. In class you learned how to do normal things like write essays and speak Spanish—you didn’t perform slave labor.

Did I say I’d learned to keep my anger under control? I may have been exaggerating.

I left the cafeteria and marched down the hallway. The corridor turned, turned again—and then dead-ended at a stone wall. I thought I’d been heading toward the front entrance, but somehow I’d taken a wrong turn.

I retraced my steps until I found a hallway that led off to my left. The yellow globes hanging from the ceiling looked familiar, and I hustled toward them. But when I reached the lights I wasn’t in the atrium, or anywhere else I remembered.

From somewhere came a moan. A voice pleading. My right leg burned like it was in ice water, but I ignored it.

I slowly walked forward until I came to a set of double doors that hung slightly ajar. The light beyond seemed marginally brighter than that of the hallway. I pushed through.

It was a library. The bookshelves were a dozen feet tall, much taller than seemed practical for a high school. The books, too, were larger and more massive than the books in my old library in California, as if each were an unabridged dictionary. The voice came from somewhere in the stacks.

I edged around the corner of a row. A white-haired man in a gray cardigan sweater stood in front of the shelves, waving his fingers in the air. Though he wore thick glasses, he blinked furiously as if he couldn’t get his eyes to focus. “No no no,” the man said to himself. “It’s got to be here; it must be.…”

“Can I help you?” I asked.

The man spun to face me, shocked. Then he glanced behind him and said, “Are you speaking to me?”

“I’m sorry, I just thought—”

“What did you mean, help me?”

I wasn’t sure how I could help, just that he sounded so desperate. Maybe he was so old his vision was failing? I said, “Have you lost a book?”

“What book? Why do you think I’m looking for a book?”

“It’s a library?” I said.

“There are many types of items in a library. Maps. Periodicals. Artifacts and artwork…” He strode away from me. The floors here were the same dark stone as the hallway. The shelves themselves were thick as ship’s timbers.

“You can’t possibly be of use,” the man said. “I’ve been combing this library for… quite a while. You’re a child and I’m a trained researcher, which means that not only do I search, I do so repeatedly.”

I walked after him, curious now. “Maybe if you told me the title.”

He wheeled to face me. “The title? You ask me for the title?”

“I’m sorry,” I said again.

“Ye gods. If I knew the title, don’t you think I would have found it by now?”

He pulled at the tufts of gray hair that sprouted from the side of his head. His dusty glasses hid his eyes. “I will not despair. I will not despair.” He seemed to be talking to himself now. “It’s only a puzzle. A riddle. A mystery. I am a solver of puzzles.”

He gazed for a moment at the shelves above us, then forced his eyes away. He shuddered.

“Good luck,” I said, and started to leave.

“You’ve been touched, haven’t you?” the librarian said.

I froze. “What?”

“It’s the only explanation. You’ve been exposed, and that’s made you sensitive.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” I said.

“It’s all right, my boy. It takes time to adjust to the world you’ve found yourself in. It’s perfectly understandable to engage in denial.”

“Right. Well, it’s been great talking to you, but—”

“You’re searching for something. Of course, why else would you have forced your way in here?”

“I didn’t force anything. I just saw that the door was open and I—”

“You had no choice,” the librarian said. “I understand. For men such as ourselves, the lure of the stacks is impossible to resist.”

“Yeah. Right. So, if you’re okay…”

“I wouldn’t say that. How would you describe a man in my condition? No, don’t say it. Denial, my boy. Denial is what keeps a soul going in trying times.”

“Sure,” I said, though I was pretty sure I didn’t agree with him. “It was great meeting you, Mister…”

“Professor, if you please. Professor Freytag.”

A distant gong sounded. I felt it more than heard it.

“I really should get going, Professor.”

“What about your book?”

“Maybe later,” I said.

Freytag looked disappointed. “Very well. Off you go.” He turned away from me. Now he seemed to be mad at me. “Close the door on the way out. I don’t like to be disturbed.”

I heard the murmur of student voices, the shuffling of feet, but it was impossible to tell where it was coming from. The walls were all damp stone, bouncing sound in tricky ways. There seemed to be no active classrooms in this wing. The doors, when I found them, looked like they hadn’t been opened in years. Corridors branched at odd angles. Some of them were only dimly lit, and I had to use my phone’s screen like a flashlight. Other hallways were pitch dark; those I refused to go down. My phone was getting no bars. If I fell down some stairs I doubted anyone would find me.

My only strategy was to follow the best-lit corridors. I was surprised when this worked; many minutes later I emerged into a wide hallway and saw a familiar door: Office of the Principal. The wide staircase was off to my left. There were no students in sight.

My anger had long since disappeared. I might have given up on my escape plan, but I had no idea where Lydia was, or where my next class might be.

I pushed through the big doors and blinked at the gray sky. Still definitely not California.

The rental house was downhill, toward the bay. I started down the sidewalk. The only person out was a man sitting on an iron bench just beyond the border of the school grounds. He was jotting something in a notebook.

As I passed the bench, the man looked up and said, “Tough morning?”

“Pardon?”

He was handsome, with dark hair graying at the temples. The kind of distinguished gentleman who wasn’t a doctor but could play one on TV. His long legs were crossed at the knee, and one long arm spread out along the back of the bench. His suit was black, his shirt white as bone, his tie a sea green. On his collar he wore a silver pin in the shape of a shark. A thresher.

Oh.

He said, “I imagine our little school is probably very different from what you’re used to.”

“No, it’s great,” I said lamely.

“It’s all right. I know we’re a bit… rural.” He held out his hand. “I’m Principal Montooth.”

I’d never had a principal try to shake hands with me. “Harrison Harrison,” I said. “Pleased to meet you.”

His grip was firm. He held it for a bit too long. “You’re not the first person I’ve met with that name,” he said. “Your father was an anthropologist, wasn’t he?”

“You knew my dad?”

“Know is too strong a word. I met him when he visited the area a while ago.”

A while ago? At least thirteen years: Dad died when I was three. I had no idea he’d been here before. Mom had never mentioned it.

A dark car, an old-fashioned sedan with tall rear fins, rolled up to the curb. Montooth stood up. He was tall—taller even than Mrs. Velloc. “This is my ride,” he said. “You enjoy your afternoon. I think we can agree that half a day is enough of a start.”

“Uh…”

“See you tomorrow, Harrison. Bright and early.” Montooth clapped me on the shoulder, then got into the passenger side of the car. The vehicle rumbled away, then turned off halfway down the hill.

I wasn’t sure what to do. Was this a trick? Had the principal seriously told me it was okay to skip school?

I glanced back at the wooden doors, then shook my head. Kidding or not, Montooth was right. A half day was quite enough of Dunnsmouth Secondary.

Excerpted from Harrison Squared © Daryl Gregory, 2015