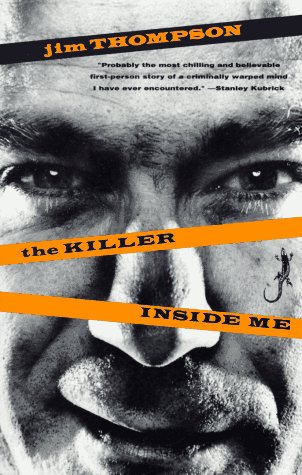

Jim Thompson, a twentieth century American pulp author of more than 30 novels, is infamous for writing some of the darkest noir ever put to page. Stephen King, who counts Thompson among his favorite authors, wrote with a kind of awe of Thompson’s bleak stories. “There are three brave lets” in Thompson’s writing, King explained in the introduction to Thompson’s Now and On Earth: “he let himself see everything, he let himself write it down, then he let himself publish it.” While adapting Jim Thompson’s novel The Grifters for film, director Stephen Frears noted a relationship between Thompson’s work and certain elements of classical Greek tragedy. Thompson’s raw, stripped-down noir informs and feeds back into these elements in a hellish kind of positive feedback loop; together, they create an unrepentantly bleak—but absolutely recognizable—vision of modern life. Nowhere is this relationship more evident than in Thompson’s 1952 masterpiece The Killer Inside Me.

Killer does its due diligence with regard to traditional noir tropes. The main character, small-town sheriff Lou Ford, is obsessed with righting a wrong. His brother, he believes, was killed by a corrupt local magnate. Ford conceives a plan to bring the man down, outside the law, by setting his son up with a local prostitute. Ford falls in love with the woman himself, but follows through with his scheme: to kill both the prostitute and the son and make it look like a murder-suicide. The plan unravels in the best noir tradition, driving Ford to kill again and again to cover up his first crime. The murders become increasingly brutal as Ford’s desperation grows, but Ford remains convinced until the end that he’s entirely in control and can, ultimately, get away with it. By the novel’s conclusion, Ford is in jail and reflecting, in his characteristically methodological fashion, on his crimes, his motivations, and his own sanity.

Ford’s story is clearly tragedy-inflected. Ford is a powerful, trusted, and well-respected member of his community. He’s smart, handsome, has a beautiful fiancée and, superficially, everything to live for. Ford’s downfall is the result of something inside him, what he privately calls the Sickness—his violent tendencies. And it is these internal compulsions that determine Ford’s progress toward self-knowledge.

The deeper Killer moves into Ford’s psyche, however, the more evident it becomes that Thompson is using the twinned genres of noir and tragedy to reinforce and amplify each other. Ford is a victim, a perpetrator, and a suspect of his own crimes, and each decision he makes drives him further toward an inevitably violent end—all according to noir tradition. He loses status in his community as his crimes pile up: he alienates the people who trust him and care about him, even driving his father-figure to suicide, all hallmarks of classical tragedy. Through it all, Ford remains ignorant of the town’s growing mistrust; it’s only at the novel’s conclusion, when he’s trapped with no real hope of reprieve, that he begins to consider where he went wrong. Self-awareness achieved during a work’s dénouement is another hallmark of tragedy. But Ford’s self-awareness is tempered by the novel’s noir characteristics.

Even as Ford considers the mistakes he made that led to his crimes being revealed, he can’t take responsibility for his behavior. It isn’t his fault that he’s become a brutal killer; it’s his father’s fault because Ford had had an underage affair with the family housekeeper, over which his father shamed and punished him. “I’d been made to feel that I’d done something that couldn’t ever be forgiven,” he reflects: “I had a burden of fear and shame put upon me that I could never get shed of.” But even then, it’s not just his father’s fault. It’s the entire town’s fault, for keeping him bored, resentful and trapped. “If I could have got away somewhere, where I wouldn’t have been constantly reminded of what had happened and I’d had something I wanted to do—something to occupy my mind—it might have been different,” Ford conjectures. But, he concludes, he’d have been trapped anywhere. Because you can’t escape your past, your circumstances, or yourself: “you can’t get away, never, never, get away ”

And then Thompson adds one last twist. He undercuts Ford’s great moment of self-awareness by making Ford unable to assume responsibility for his actions, and then undercuts it again by making Ford present an argument questioning his own sanity. The last full paragraph of the novel finds Ford considering, even quoting, German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin’s work on paranoid schizophrenia. By including text from an external, non-fictional source, Thompson gives his audience the opportunity to make up their own minds about Ford’s ultimate culpability. Ford murdered to revenge himself on a man outside the law, but he believes he’s not ultimately responsible for being a murder, because his father’s actions made him what he is. And then, underneath that, the reveal that Ford may truly not be to blame—he may, actually, be clinically insane.

Lou Ford is the beating heart of The Killer Inside Me. He’s a twisted psychopath, a pathological liar, a sexual deviant, and a vicious killer: an intensely and unquestionably brutal man. But he’s a compelling man, as well—even as we hate him we feel a kind of pull toward him, even an empathy with him. He’s smarter than everyone around him. He’s trapped in his podunk town, a town rife with petty corruption and ugly secrets and the grinding, mind-destroying dullness of existence we all know. The emotional catharsis of tragedy comes from the way it creates fear and pity in the audience. We fear Ford, because he’s a monster. But we pity him, because we see in him a tiny flicker of ourselves. Because we’re all trapped.

Stephen King quoted from the introduction to Now and On Earth. Black Lizard, 1994. Page ix.

All quotations from The Killer Inside Me come from Jim Thompson: Four Novels. Black Box Thrillers, 1983. Pages 233, 235.

Anne C. Perry talks the big talk over at Pornokitsch, a geek culture blog. She’s supposed to be working on a Ph.D., even though she seems to spend most of her time thinking about monster movies.