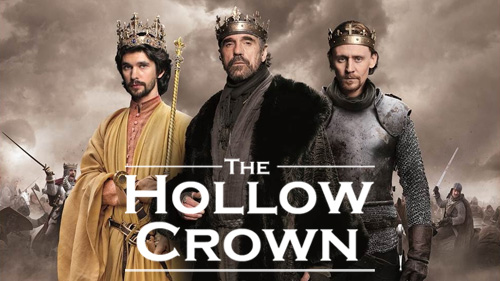

Most genre fans who know about the 2012 BBC television film series The Hollow Crown know it because of its big name cast: Jeremy Irons, Tom Hiddleston, John Hurt, Patrick Stewart, Ben Whishaw (Cloud Atlas and Skyfall Bond’s new Q) and Michelle Dockery (Downton Abbey). And now that series 2 has signed Benedict Cumberbatch and Downton Abbey’s Hugh Bonneville, the fan squeal almost threatens to drown out the writer credit: Shakespeare.

There have been many discussions of how Netflix, Tivo and their ilk have transformed TV consumption, production and money flow, but I spent the last year watching a pile of different (filmed and live) versions of Shakespeare’s Richard/Henry sequence in order to focus in on how the Netflix era has directly impacted, of all things, our interpretations of Shakespeare, and what that tells us about historical and fantasy TV in general.

More than once I’ve heard a friend answer “What is The Hollow Crown?” by saying, “The BBC wanted to capitalize on Game of Thrones so did Game of Thrones-style versions of the Shakespeare Henry sequence, since GoT is basically the Wars of the Roses anyway.” This is only half true, since The Hollow Crown was already contracted in 2010, before Season 1 of Game of Thrones aired in 2011 and demonstrated just how big a hit fractious feudal infighting could be. Rather, both the Game of Thrones TV adaptation and The Hollow Crown are, like the two Borgia TV series that came out in 2012, reactions to the previous successes of big historical dramas like The Tudors and HBO’s Rome. TV audiences have long loved historical pieces, but this particular recipe of the long, ongoing grand political drama with corrupt monarchs, rival noble houses, doom for the virtuous, and a hefty dose of war and sex is new, or at least newly practical, for two key reasons.

The first enabling factor is budget. In recent years, a combination of special effects getting cheaper and profits growing (as the streamlining of international rebroadcasting means shows can reliably count on foreign sales to help make back costs) means that today’s historical dramas can depict epic vistas, long rows of fully-costumed soldiers, and even grand battling hordes undreamt of by their predecessors like I Claudius (1976), which, for all its brilliance, had to do the grand gladiatorial displays entirely off-screen by just showing the faces of actors pretending to watch them.

The other big change is the new wave of consumption tools: Netflix, TiVo, on-demand, DVD boxsets, streaming services; these make it easier than ever to binge an entire show in a short time span, and eliminate the risk of missing an episode and having no way to catch up. This has made it infinitely more practical for studios to abandon the episodic reset button and produce long, ongoing plotlines, since they don’t have to worry about losing viewers who miss one installment. While this has culminated with direct-to-Netflix series like the American House of Cards remake, designed to be binge-watched without any serialization, the changeover has been developing for a long time—its first rumblings appeared in the era of VHS home recording, when Twin Peaks set records for being recorded en mass by its fans, demonstrating how new technology could give audiences new power over the when of watching.

We can see the direct effects of all this change by focusing on Shakespeare. Shakespeare’s Henriad is his sequence of consecutive historical plays, which, if performed together, tell a continuous narrative from about 1397 to 1485, starting with the drama around the overthrow of Richard II, then running through exciting rebellions in Henry IV Parts 1 & 2, then Henry V’s invasion of France taking us to 1420, and if you add on the three parts of Henry VI you gain the Wars of the Roses, Joan of Arc, witchcraft, and, as the cherry on top, the juicy villainy of Shakespeare’s version of Richard III. The period and events are perfect for our current style of historical drama, complete with the frequent dramatic deaths of major characters, and Shakespeare provides about 18 hours of prefabricated scripts to work from, complete with guaranteed excellent dialog and efficient exposition. Shakespeare’s ability to feed the modern TV appetite for crowns and thrones had already been proved by The Tudors which mixed the best selections from Shakespeare’s Henry VIII with lots of original material, filling in the juicy parts which Shakespeare was too cautious to mention in front of said Henry’s successors. Using the eight Henriad plays provided The Hollow Crown series with even more plot and even less need to supplement it.

But this is not the first time the BBC has filmed Shakespeare’s Henriad for TV serialization, it’s actually the third, and that’s what makes it such a great opportunity to look at how the Netflix era has changed TV historical dramas. In 1960 the BBC produced An Age of Kings, which, over thirteen hour-long episodes, covers precisely the same sequence, Richard II to Richard III with all the Henry action in between, featuring stars of the day including Robert Hardy, Tom Fleming, Mary Morris and a very young Sean Connery.

Then from 1978 to 1985, in the wake of such exciting advances as color, the BBC Shakespeare Collection project filmed every surviving Shakespeare play, and once again linked the Henriad together with a continuous cast and relevant clips of flashbacks from later plays to earlier, and stars including Anthony Quayle and Derek Jacobi. Screening all three versions side-by-side provides a mini-history of historical TV dramas and the evolving viewer tastes they aim to satisfy. And adding in other versions—the Henry Vs done by Laurence Olivier (1944) and Kenneth Branagh (1989) and the recent on-stage productions of Henry IV done by the Globe (available on DVD) and Royal Shakespeare Company (still playing live)—provides even more snapshots.

Aesthetic differences are perhaps the most obvious. The earlier filmed and current staged versions went with traditional brightly colored livery, especially in the battle sequences where recognizing coats of arms makes it easier to tell armored nobles apart, while The Hollow Crown opted instead for lots of leather, dark colors and visible armor, the sorts of costumes we’re used to from action flicks and fantasy covers.

Dark, quasi-fantasy costuming is a choice that flirts complexly with the term ‘anachronism’ since every garment depicted is ‘period’ in that would plausibly have existed at the time, but the costumers have opted for all the ones that fit our post-Matrix-movies cool aesthetic and against other more plausible designs which don’t. Certainly any given noble in Henry IV might choose to leave off his brightly colored tunic in battle, or wear all black at Court, but putting them all in bare plate and black is an active choice, like a director making every single businessman at a board meeting wear the same color necktie. Anyone watching the History Channel’s Vikings series is similarly enjoying the costumers’ decision to have everyone in iron and leather instead of the bright orange cloaks and stripey trousers that are more probable for the period, but just don’t feel cool.

It’s taste. We get weirded out when we see ancient Roman white marble statues and temples painted garish colors—the way research now tells us they once were—and we want the Middle Ages to be brown and black and deep blood red, rather than the brilliant saturated colors that medieval people loved. And frankly, I sympathize with both impulses. After all, it’s delightful seeing really well-researched costumes, but I also get a thrill down my spine when a crew of fantastic-looking medieval warriors strides over a hill.

Here, then, compare the BBC Shakespeare and Hollow Crown costumes for kings Henry IV and Henry V, and think about how both versions feel period and awesome in totally different ways. The BBC Shakespeare is all costly princely fabrics, elaborate sleeves and regal jewelry, while the Hollow Crown gives us black and blood red, grim medieval furs, cool fingerless gloves and lots of leather. (Keep in mind that the BBC Shakespeare images are faded, so would look much brighter if they were cleaned up; Hollow Crown is dark on purpose.)

Did wide, studded leather belts and tightly-tailored leather shirts like that exist at the time? Sure. Would Henry have worn one instead of showing off his wealth with gold and giant fur-lined brocade sleeves? Probably not, but the leather tunic is still effective in a different, successful and immersive way.

Another big difference over time is in how much screen time is given to non-dialog. The battle scenes and duels have always been a thrilling centerpiece of Shakespeare’s historicals. In both the films and the live stage versions, rendering of the battle scenes have gotten more ambitious over time, with long elaborate duels and stunts like dual-wielding swords, and the more recent the production the more the director tends to carve out space for action sequences, often at the expense of cutting dialog. When the magic of film makes it possible, movies add impressive sets, roaring crowds and real explosions, and The Hollow Crown also takes its time with setting scenes, vistas of countryside, watching characters travel by horseback, pulling the ultimate “show don’t tell” by giving the viewer everything Shakespeare couldn’t give those seated in the Globe. And what film can do, high-tech modern stages can often approximate. Below, the magic of stagecraft as mist and shadow make Hotspur’s charge in Henry IV Part 1 cinematically extravagant even live on stage at the Royal Shakespeare Company performance in Stratford (about to play in London too). Note again how not-colorful it is:

The addition of long, scene-setting visuals in the Hollow Crown makes the whole thing feel much more like an historical epic than any of the earlier filmed versions, despite having literally the same content. While the earlier TV versions jumped as quickly as possible from scene to scene in order to cram every syllable of dialog they could into limited air time (and working in an era when every inch of film shot was a bite out of the BBC’s budget) the modern big budget digital production has the leisure to establish a scene, and make it genuinely easier to keep events and places straight. For example, in The Hollow Crown version of Richard II we actually see the banished Henry Bolingbroke return to England and be received by Northumberland, an event which Shakespeare has happen off-stage, but remains a giant plot point throughout Henry IV 1 & 2, so the whole long-term plot of the sequence is easier to follow and feels better set up when we see this dialog-free extra scene.

Another happy change is that The Hollow Crown version has done an extraordinary job treating the homosexual undertones which have always been present in Richard II, but which were hidden as much as possible by many earlier directors, including the 1960 and 1980s versions. Richard through the Hollow Crown is costumed in gold or white, a brightness which at once feels appropriately opulent and effeminate, and in contrast makes the literally black days of his usurping successor Henry feel extra stark and grim. Even his crown is more colorful and ornamented, with gems and floral decoration. In addition to being less homophobic than most of its predecessors, The Hollow Crown, like all the recent adaptions, tones down the racist elements of Shakespeare’s period humor, making the Irish, Welsh and French characters more positive (though in Henry V it was surreally ironic to see The Hollow Crown replace Shakespeare’s period racism by killing off the only black guy).

But there is a more central challenge in turning Shakespeare’s Henriad into something which will genuinely please modern Netflix audiences—a broad, structural challenge most clearly visible if we narrow in on Henry IV Parts 1 and 2.

What is Henry IV Actually About?

Even with the same text, editing and direction can change these stories more than you might imagine. If you showed different versions of Henry IV to people who’d never seen it and asked them to write plot summaries you’d think they’d seen completely different plays. A look at the DVD covers makes this crystal clear:

What are these plays about, the prince, the tavern or the king? The structure of Henry IV makes it particularly easy for the director to change the answer, since for much of both plays the action literally alternates between funny scenes at the tavern, with Prince Hal and his old friend Falstaff playing drunken pranks, and scenes of war and politics with King Henry IV facing bold rebels. The two halves are united by the process of the young prince gradually facing up to his political destiny, but the director can completely change which half seems to be the thrust of it by deciding which scenes to do quickly and which to do slowly, which to trim and which to extend with music or dance or horse chases or battle drama.

We know that in Shakespeare’s day the big hit was Prince Hal’s funny friend Falstaff, who was so popular in Part 1 that Shakespeare added a ton more (completely gratuitous) scenes with him in Part 2 plus wrote the entire comedy The Merry Wives of Windsor just to give us more Falstaff—pandering to one’s fans is not a modern invention! But the modern audience of The Hollow Crown is in this for the high politics dynastic warfare epic, so the director has made the shockingly radical decision to give us a version of Henry IV which actually seems to be about King Henry IV.

Below on the left, Prince Hal smirks at Falstaff’s antics in the Globe production of Henry IV (portrayed by Jamie Parker and Roger Allam) while on the right, Hal is being told off by his father, King Henry IV in The Hollow Crown (Tom Hiddleston and Jeremy Irons). Both scenes appear in both versions of the play, but guess which is extended and which trimmed?

Only part of this shift comes from directors actually cutting lines, though The Hollow Crown, like its 1960 Age of Kings predecessor, does trim the silly scenes and extend the serious. What makes focus feel so different is the emotion and body language behind an actor’s delivery, which can make a line have a completely different meaning. For anyone who wants an amazing quick demo of this, check out two short videos Mercator A and Mercator B, created by an NEH Workshop on Roman Comedy, demonstrating how the same short scene from Plautus’s ancient play feels completely different without changing a word—the jealous wife’s body language is altered. (The hard-core can also watch the scene in Latin where body language alone tells all).

For me, in Henry IV, the centerpiece issue is how any given director chooses to present Falstaff, the vice-ridden, drunken, witty, thieving, lecherous, eloquent old knight with whom our young trickster Prince Hal plays away his youthful hours. The crux of this is the finale of Henry IV part 2 when (415-year-old spoiler warning) Prince Hal becomes King Henry V and, rather than taking Falstaff to court as one of his favorites, suddenly banishes Falstaff and all the immoral companions of his youth. This decision wins Henry the respect of his nobles and subjects, but breaks Falstaff’s heart and hopes, resulting in the old knight’s death. How Falstaff and Henry’s nobles react is locked in by Shakespeare’s script, but it’s up to the director and the actors to determine how the audience will react—by deciding how to present Falstaff, Prince Hal and their relationship to the audience throughout the four-plus hours leading up to Hal’s decision.

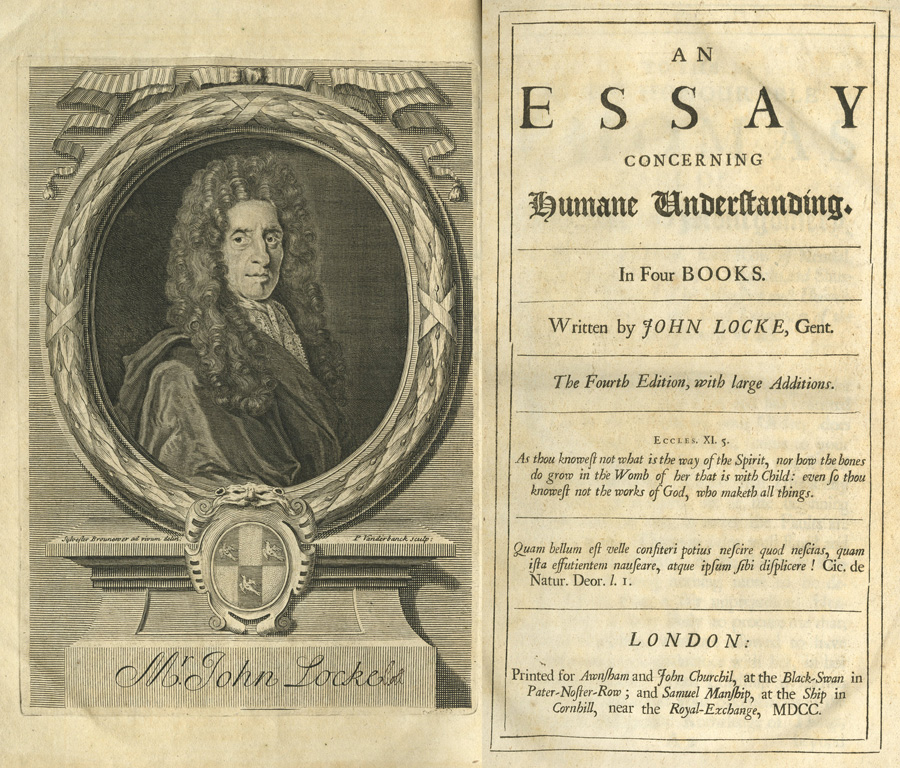

And here I must introduce the great invisible adversary faced by all these adaptations, film and stage alike: John Locke. What does John Locke have to do with how much we like Falstaff? The answer is that his 1689 essay on human understanding radically changed how we think about human psychology, and in turn how we think about character progression, and plausibility.

Everyone gets thrown out of a story when something we consider deeply implausible happens. It could be an unsuccessful deus ex machina (just when all hope was lost a volcano suddenly opened up under the villain’s feet!), or a glaring anachronism (and then Cleopatra pulled out her musket…), but often it’s an implausible character action, a point at which the reader simply doesn’t feel it’s in character for Character X to make Decision Y. At best it is something we can shrug off, but at worst it can throw us completely, or feel like a betrayal by the character or the author.

This issue of what decisions are “in character” or plausible gets trickier when we look at material written in earlier historical periods because, in the past, people had different ideas about human psychology. What actions were plausible and implausible were different. This is not just a question of customs and cultural differences—we are all aware that different eras had different cultural mores, and we’re ready for it, even if we might be a bit thrown by when characters in classic works voice period sexist, racist, or other alienatingly un-modern cultural views.

I’m discussing something different, a fundamental difference in how we think human minds work, and, above all, how we think they develop. For example, the anti-love-at-first-sight messages of Disney’s Brave and Frozen, represent (among other things) the broader social attitude that we don’t find it plausible anymore for the prince and princess fall in love after knowing each other for five minutes (also a tricky issue for modern performances of the princess-wooing scene in Henry V). And this is where the real barrier between us and contentedly enjoying Shakespeare is John Locke’s 1689 Essay Concerning Human Understanding.

When you look at pre-Locke European literature, and also at a lot of pre-Locke scientific literature about the human mind and psyche, the big focus tends to be on inborn character and character flaws, and attempts to overcome them. The model is that a human is born with a prefab character or set of propensities, and a prefab palette of virtues and vices, which will either make the person fail or be triumphantly overcome. We see this all over: Plato’s claim that the majority of human souls are irredeemably dominated by base appetites or passions but a few have the ability to work hard and put Reason in charge; the “science” of physiognomy which strove for centuries to figure out the personality from the inborn structure of a person’s face and head; philosophers from Aristotle and Seneca to Augustine to Aquinas talking about how the best way to become virtuous is to identify your flaws and overcome them through rote repetition. We also see it all over pre-modern fiction, from the Iliad where we watch Achilles wrestle with his great flaw anger, to noble Lancelot marred by his weakness to love, to the Inferno where Dante’s journey helps him overcome his tendency toward sins of the she-wolf, to Shakespeare.

John Locke, then, was one linchpin moment in a big change in how we think about psychology (aided by others like Descartes on one end and Rousseau and Freud on the other). This transformation led to a rejection of old ideas of inborn character and character flaws, and replaced them with Locke’s famous tabula rasa idea, that people are born inherently blank, and growing up is a process of forming and creating one’s character based on experiences rather than watching a prefabricated inborn personality working forward to its conclusion. This new idea became extremely widespread in Europe with amazing speed (thanks to the printing press and the Enlightenment) and resulted in a remarkably quick change in how people thought people thought.

This was in turn reflected in fiction, and created a new sense of how character progression should work. The post-Locke audience (whether reading Austen, Dickens, Asimov or Marvel Comics) expects to watch a character develop and acquire a personality over time, gaining new attributes, growing and transforming with new experiences. If the character has deep flaws, we expect them to be the result of experiences, traumas, betrayals, disasters, a spoiled childhood, something. We generally aren’t satisfied if the villain is evil because she or he was born that way, and we love it when an author successfully sets up a beloved character’s great moment of failure or weakness by showing us the earlier experience which led to it. This is an oversimplification, of course, but the gist of it gets at the issues as they relate to Shakespeare’s reception today.

Writing circa 1600, Shakespeare is about as modern as a European author gets while still writing pre-Locke. This puts him in a particularly difficult position when it comes to getting modern audiences to accept his characters’ actions as plausible. Even in Romeo and Juliet directors hard work to get the modern reader to accept love so intense and so instant, and Hamlet’s psychology is an endless and elaborate puzzle. Hal’s betrayal of Falstaff is one of the very hardest cases of this. The audience has just spent five hours bonding with the hilarious Falstaff, and now Hal is going to betray and destroy him. But we then have to spend another entire play watching Hal, so we need to still like Hal after he casts out Falstaff. Thus, the performance needs to show us motivations for Hal’s action which we can understand, sympathize with, respect, and generally accept.

Shakespeare offers us plenty of forewarning of Hal’s choice, but, unfortunately for the modern director, it’s forewarning that fits very well with the pre-Locke fixed-personality-with-character-flaw idea of psychological plausibility, but much less well with the post-Locke developmental model. At the beginning of Henry IV Part 1, just after our first fun tavern scene, Hal gives a speech in which he point blank states that he is being raucous and disreputable on purpose to make people think he will be a bad king, so that when later on he changes and is good and virtuous his virtues will seem brighter and more amazing given the low expectations everyone had, and he will thus command obedience and awe more easily. His intention to throw away Falstaff and his other friends is set from the beginning.

Later in the same play, when Hal and Falstaff are playing around imitating Hal’s father King Henry, Hal-as-Henry hears Falstaff make a speech begging not to be banished, and Hal says to his face “I will” making his ultimate intent clear to the audience if not necessarily to Falstaff. And in both Part 1 and Part 2 Hal’s interactions with Falstaff are mixed with occasional criticisms of Falstaff, and self-reproachful comments that he should not be wasting his time at taverns, while Falstaff too sometimes complains of his own vices and says he intends to repent.

The pre-Locke psychological model makes all this fit together very neatly: Hal was born good and virtuous but with a weakness for playfulness and trickery, but he manages to turn that inborn vice into a virtue by using it to enhance his own reputation, unite his people, and later (in Henry V) to expose traitors. His rejection of Falstaff is nobility’s triumph over vice, and the good Shakespearian audience member, who has sat through umpteen Lenten sermons and passion plays, knows to respect it as the mark of a good king, who may not be as fun as a drunken prince, but will do England good. This did not prevent Henry V from being much less popular in its opening run than the earlier Falstaff-infused installments of the Henriad, but it did make sense.

The developmental model makes all this much trickier. If Hal really has decided from the very beginning to string Falstaff along and then betray and destroy him without any word of warning, it’s hard for Hal not to come across as cruel and manipulative, and it’s also hard for a modern audience to accept a prince who was upright and virtuous the whole time but ran around being raucous in taverns for years just because… of… what? It is here that the individual actors’ and directors’ choices make an enormous difference, both in how they present Hal’s decision and how appealing they make Falstaff.

Falstaff can be (as he is in the recent Globe and Royal Shakespeare Company productions) show-stoppingly, stage-stealingly hilarious, delivering all his absurd and nonsensical jests with brilliant comic timing, so you’re almost eager for the battles to be over so you can have more Falstaff. Or he can be (as he is in the 1960 Age of Kings) a conversational tool for Prince Hal designed to show off our beloved prince’s wit and delightfulness, cutting many of Falstaff’s lines to minimize how much the audience bonds with him and make as much room as possible for the long-term protagonist. Or, as in The Hollow Crown, he can be portrayed as a remarkably unappealing and lecherous old man who mutters and rambles nonsense jokes that are too obscure to even be funny, so you spend your time wondering why Hal is wasting his time with this guy. This is not a difference of acting skill but of deliberate choice, highlighting the moments at which Hal is critical of Falstaff (or Falstaff is critical of himself) and racing through the jests instead of stringing them out, focusing the play (and the audience’s attention) more on Hal’s choices and less on Falstaff’s jokes.

All these productions are struggling with the same problem, how to make Henry’s actions plausible and acceptable to audiences who are judging him developmentally instead of as a fixed character struggling to make a virtue out of his inborn flaw. The hardest part is his speech at the beginning about how he is delaying his reformation deliberately. Without that we could easily see him growing gradually more disillusioned with Falstaff, especially if we lengthen the time spent on the critical sections more as the plays advance to make it seem as if he’s gradually coming to see Falstaff’s flaws (though he does in fact criticize Falstaff throughout). But that isn’t possible after the opening statement “I’ll so offend to make offense a skill/ redeeming time when men think least I will.”

All take different approaches to the dismissal scene, exposing their different long-term strategies.

The 1960 Age of Kings version starts from the very beginning with Hal seeming annoyed and cranky at Falstaff, wincing at his stink and suffering a headache talking to him, while Falstaff’s lines are funny but fast and babbled with more camera time on Hal’s silent reactions than on Falstaff’s wit. Thus when the speech comes we are content to see this fun and charming young prince criticize and propose to throw aside his unpleasant companions, and if his declaration that he intends to “falsify men’s hopes” make us uncomfortable, the director helps by making exciting war drums and battle trumpets start up when he gets toward the phrase “make offense a skill,” reminding us that we won’t get England’s triumph at Agincourt without Hal’s good planning now.

The 1970s BBC Shakespeare Collection version is less confident in our willingness to accept a manipulative Hal. It very cleverly has him deliver the speech slowly with a sense of awe and discovery, to himself rather than to the audience, as if his wildness was genuine until this moment and he has only just now thought of how to “make offense a skill” and turn his flaw into a virtue. This works very well for the developmental model, as if Falstaff’s grossness in the preceding scene was a turning point, and we’ve just seen the first step of Hal’s progression toward the great king he will become. This Hal will be consistent with his later playful tricksterish impulses in Henry V, but won’t seem two-faced or cruel for how he used Falstaff.

The Hollow Crown takes an even heavier hand in reshaping this scene and its meaning entirely. It presents an even more unappealing Falstaff, cutting almost all his jokes, instead showing him lying beside (and being mean to) a prostitute, pissing in a pot, and struggling to put on his own boots since he’s so lazy, fat, and out of shape (the fat jokes are original to the text and also awkward to handle in the modern day). Visual cuts are also used to alter the scene more. Rather than having us watch a lengthy scene of Hal at the tavern, we cut actively back-and-forth between the tavern and the council scene with King Henry IV which normally precedes it, juxtaposing prince and king, peace and war.

The tavern scene is also framed, on the front end and back, with grand establishing shots undreamt of by earlier or stage budgets, in which we see the town streets outside the inn, occupied dozens of filthy peasants and goats, with blood from the butcher’s stall mixing in the mud. Hal’s speech, then, is delivered as a melancholy voice-over as he surveys the wretched state of his future subjects, and its beginning “I know you all, and will a while uphold/ the unyoked humor of your idleness…” isn’t about Falstaff and company at all, but the general filthy and squalor-dwelling population of London.

Thinking of the plays as a continuous series now, it was these people’s wickedness, ingratitude, and scorn that caused the overthrow of Richard II and the rebellions which threaten Henry IV. It is they whom Hal must win over if he is to ensure any peace for England when he becomes king. The viewer’s sympathy is entirely with Hal, seeing the tattered and war-torn state of England and endorsing his albeit tricksterly plan for its recovery, and we have not a jot of regret at the overthrow of Falstaff who is an unappealing and unrepentant old degenerate whom we are glad to see Henry use as a tool for England’s salvation. The tavern scenes are now about politics too, and the modern TV consumer, who probably popped in the DVD hoping for war and politics rather than clowns, may well prefer it that way.

The Hollow Crown’s solution to the Falstaff problem, which we could also call the Hal’s development problem, is only possible thanks to how thoroughly the director has stepped back from the text to concentrate on the overall historical epic. As someone who loves a good Shakespearean clown, I quite missed the lively Falstaff I was used to when I first watched this version, but it certainly made the war easier to understand than usual, and it also made me care more about Henry IV than I ever had before. Thus, while funnier productions of the Henriad will remain my favorites, I quite look forward to seeing what the Hollow Crown team will do with the three parts of Henry VI, which have always been ranked among Shakespeare’s weakest plays, but have so many battles and council scenes that direction oriented toward epic will likely make them shine.

Both earlier TV versions of the Henriad were, like the stage productions and stand-alone films, still more about presenting Shakespeare’s text than they were about the histories surrounding England’s wars and kings. The Hollow Crown seems to use Shakespeare’s script as a tool, with the battles and overall narrative as its focus—this different mode of production creates characters that are more comfortable and “plausible” in the eyes of modern TV viewers, especially those used to watching any number of historical and historical-fantasy dramas like The Tudors, The Borgias, Rome, and Game of Thrones. Such an adaptation of Shakespeare has new and interesting potential.

In fact, this points us at one of the great assets that the Game of Thrones TV series enjoys compared to the non-fantasy historicals: its characters’ actions and motivations were plotted by someone influenced by a modern sense of developmental psychology and character consistency. George R.R. Martin’s books have the leisure of exposition and character point-of-view to directly highlight character’s thoughts and motives. Even the TV series, which has stripped away any inner monologuing, is still relateable because the audience shares the author’s general understanding of character and human behavior.

Conversely, when we look at Rome or The Borgias or I Claudius, the surviving primary sources were all written by people who do not share our views on human development and personality, so their accounts of why Henry VIII executed Anne Boelyn, or why Emperor Claudius married the obviously wicked Agrippinill won’t satisfy modern assumptions about what is plausible. Directors of these historical dramas have had to create their own original interpretations of historical figures’ actions, working to make them feel relatable and realistic to today’s audiences.

So while these Netflix binges and big budgets are bringing us more long, ongoing historical dramas (where we actually get to see the battle scenes!), they are also making it harder for modern TV audiences to accept watching Shakespeare straight. We are now used to historical dramas that include modern psychology and character motivations, ones we can accept as plausible and familiar if not sympathetic, just as we’re used to seeing kings and Vikings in black and leather instead of puffy sleeves and stripes. Shakespeare’s text doesn’t give us comfortable motivations like that, not without the extreme directorial intervention seen in The Hollow Crown.

If we want to play the Henriad straight, as the recent live Globe Theater and Royal Shakespeare Company productions did, letting the audience fall in love with a charming and lively Falstaff will lead to shock and grief at his fall. The live stage productions make the audience feel a little better by having Falstaff come back for his curtain call all smiling and safe, but TV versions can’t offer such a consolation if they choose to let us face the full brunt of the shock a modern person faces when we give ourselves into the power of pre-modern writers. (If you ever want to experience true historico-mental whiplash I dare you to watch to the end of the courageously authentic new Globe Taming of the Shrew.)

In 1960 and 1980, when comparatively few long, continuous historical shows were on, and more of them were heavily based on historical sources with less addition of innovative new motives, perhaps it was easier for the original audiences of Age of Kings and the BBC Shakespeare Collection to accept what Hal does to Falstaff, just as it was easier for them to accept Henry IV’s froofy hat and Livia pretending to watch off-screen gladiators—something audiences now would definitely not put up with if the BBC tried it again in their new I Claudius remake.

And, of course, our models of psychology themselves have changed since 1960. John Locke’s model of psychology has not reigned unaltered since the seventeenth century, and Freud deserves his due as a large influence on how we think characters should plausibly behave (especially given how common ‘trauma’ and ‘repressed urges’ are as motivations in modern fiction). In addition, discoveries about brain structure and development, our greater understanding of many psychological disorders, and the greater visibility of psychological issues are also more rapidly entering public discourse, which is reflected in the media we consume.

The Henriad productions I’ve talked about provide just a few examples of this changing media landscape. As we continue to talk about technology’s evolving affects on how we create, consume, market, and structure fiction, we should also keep in mind medical, psychological, and philosophical advancements similarly transform how we watch and read, as well as how we shape or reshape stories to suit a modern audience.

Ada Palmer is an historian, who studies primarily the Renaissance, Italy, and the history of philosophy, heresy and freethought. She also studies manga, anime and Japanese pop culture, and has consulted for numerous anime/manga publishers. She writes the blog ExUrbe.com, and composes SF & Mythology-themed music for the a cappella group Sassafrass. Her first novel is forthcoming from Tor in 2015.