The question of what factors drive historical change has intrigued historians from the very beginning, when the earliest scholars first turned their attention to studying and interpreting the past. To find the answer(s) to this key question, historians make use of social science theories. These theories help make sense of the inherent contradictions found in human behavior and human society.

For example, there is the theory that shifting generations drive historical change—as in, as one generation dies off, it’s gradually replaced by another with a different set of values and priorities. The many “Millennials vs. Boomers”-related hot takes of the moment are examples of this view of history.

Technological innovations have often been viewed as driving historical change. Usually, one innovation in particular is given credit for changing the world: for example, the introduction of the printing press in 15th century Europe, or the invention of the Internet towards the end of the 20th century.

Race has also been used to explain historical change, especially in the form of scientific racism. Scientific racism is an amalgamation of Imperialism and social Darwinism, which is Charles Darwin’s “survival of the fittest” applied to industrial capitalism. The application of scientific racism is where problematic concepts of historical change brought about by the supremacy of white men find room to breath, which in turn provides the foundation for the alleged superiority of western civilization.

Historians today have largely abandoned these theories because they are reductionist, and, in the cases of scientific racism and social Darwinism, also based on pseudo-science. We use the term “reductionist” because these theories reduce complex historical processes to a single cause or event, which leads to a skewed representation of history. This is where certain individuals, organizations, and institutions are written out of history simply because they don’t fit the mold or don’t fit into a selective narrative.

Instead, modern historians use theories that take in as many aspects of society as possible and which avoid making any kind of predictions. One such theory is the theory of the long duration (la longue durée), which is based on the relativity of time. Another is the theory of structuration, which is based on the interaction between individuals and structures that causes change from within society. Historians also use theories of socio-economics, social networks, and the distribution of power.

But even though historians have moved on to more complex theories to attempt to explain historical change, reductionist theories are still employed in fiction and certain genres of popular history. Why? Because they often make for very compelling storytelling.

One of the most persistent reductionist theories to explain historical change is The Great Man Theory, which explains history as the result of actions taken by extraordinary individuals who, because of their charismatic personalities, their superior intellect, or because of divine providence, single-handedly changed the course of history.

The Great Man Theory has been attributed to Scottish philosopher Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881), who stated, “the history of the world is but the biography of men,” providing names such as Martin Luther, Oliver Cromwell, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau as examples to prove his point. If this sounds familiar, it’s because this type of history is what we tend to find on the history shelves of booksellers and libraries. Just think of the phenomenon of Hamilton, based on a biography of Alexander Hamilton, until then one of the lesser known Founding Fathers. Or take a look at the most recent winners and finalists of the Pulitzer Prize for History where not one book focuses on the great deeds of a woman, let alone mentions a woman’s name in its title. Instead we find books on the lives of men such as Frederick Douglass, General Custer, and Abraham Lincoln.

The idea of individual men driving historical change can be traced as far back as the Ancient Greeks and their ideal of excellence and moral virtue (arête, ἀρετή), but Carlyle was the one who merged history with the Renaissance idea of the lone genius as it was interpreted within Romanticism. The problem with Carlyle’s theory is that he celebrated the individual man without taking into account the larger circumstances that shaped the world and the times that that man lived in, and in doing so, tells only one part of a full, complex story of the past.

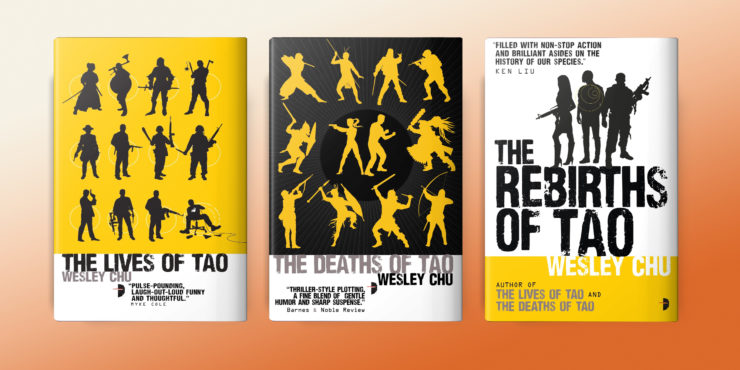

In SFF, we find a prime example of The Great Man Theory in action in Wesley Chu’s Tao trilogy, albeit with a twist. According to the Tao books, Great Men throughout history—Genghis Khan, Napoleon, Steve Jobs, to name a few—were great because an extraterrestrial alien lived inside their bodies in a symbiotic relationship. These men were great because of the capabilities of their alien symbiote, not necessarily because of any innate qualities.

Buy the Book

The Lives of Tao

Across the millennia, these extraterrestrials, known as Quasings, have manipulated humans to do their bidding so that Earth can be developed into a civilization advanced enough for the Quasings to be able to return home. The story of how the Quasings pulled this off is told through flashbacks by the Quasings who inhabit the bodies of the human main characters. They tell us that behind every major historical event stand a Quasing and his host. Individuals who have caused historical change this way are all men; according to these aliens, no woman has ever contributed to human history in any significant way.

The Tao series follows The Great Man Theory closely, and in doing so succeeds in telling an intriguing story that examines the role of the individual in history, the tension between free will and the collective, and good deeds vs. bad.

By following The Great Man Theory as closely as it does, the Tao trilogy also exposes the problems when using reductionist theories to explain historical change. Sooner or later, even an extraterrestrial symbiote runs up against events and structures larger than itself.

According to the backstory-providing Quasings, the atrocities of the Spanish Inquisition and the Thirty Years War, as well as the cause for the outbreak of the American Civil War, are the results of vicious infighting among the Quasings with fewer named Great Men the closer we get in time to the 21st century. World War II is explained as something humans caused themselves; in other words, between 1939 and 1945, for the first time since the Quasings began taking humans as hosts hundred of thousands of years ago, humans, as a collective, caused historical change on their own.

We continue to tell stories of the hero because they can be told according to a familiar, satisfying formula. In fiction, authors follow the template known as The Hero’s Journey, and we, the readers, turn the pages in anticipation of what crucible this formula will put the protagonist through next. Biographies of famous people from history tend to turn into bestsellers because the individuals are familiar to us, and because their stories, too, follow a formula–namely that of becoming a hero in spite of himself told through a narrative arc consisting of a beginning (birth), a middle (life), and an end (either death, or the emergence as hero).

The world would be a much different place without certain individuals being alive in it. Our books would not be what they are without our heroes and heroines to root for and identify with. But what drives historical change is the same thing as what drives a good story: Charismatic individuals who cause change to happen by taking action against something larger than themselves. In history, looming larger than the individual are the rigid structures of society, reluctant to change and sometimes violently so. In fiction, worldbuilding and the narrative arc set the limitations for action. In both history and in fiction, as in all good stories, we root for the hero and the heroine because they bring about change in spite of the world they live in, not because of it.

Erika Harlitz-Kern is a freelance writer and historian with a PhD from the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. When not reading and writing about fantasy and science fiction, she teaches history at Florida International University in Miami, and spends her free time in Florida’s wetlands, silently thanking the alligators for not turning her into a snack.

Interesting that the best-known SFF theory of social change is Psychohistory, which takes the idea to both extremes: social change is a collective process of unknowing (hence the secrecy of the Foundations) populations that can be perturbed by Great (Enough) individuals. Perhaps Dr. Asimov was inspired to insert the individual factors by the quote attributed to Josef Stalin: “A single death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic.” And we tend to read (and buy) tragedies faster than statistics.

How about ‘all of the above’ except for the pseudo science, as cause for historical change?

Napoleon seems to have had a good angle on his historical importance, yes he was a Great Man but the times gave him his opportunities.

The “Great Man” theory is misnamed (history also contains many great women), and if and when it reduces historic change to actions of extraordinary people it is certainly wrong.

That said, I believe that the choices made by individuals can have profound influence on the course of events. Had Mohammed, Genghis Khan or Napoleon never lived the world would look quite different. But “great men” themselves needn’t be extraordinary. Frederick of the Palatinate was a mediocre man, at best. Only an accident of birth in a aristocratic feudal society positioned Frederick to accept the Bohemian crown, when he might have rejected it and avoided the Thirty Years War, which cast a long dark shadow over German history with consequences for the whole world.

@1 Eugene R.

I was just wondering, as I read this, how Galactic history would have worked out if The Mule had been a woman.

Theories about technological change and Great Men are reductionist if you assume that’s all that’s driving history, but I wouldn’t say that means they have no effect. It’s not all just mass social trends.

Nineteenth-century Europe was heavily shaped by Napoleon. If he didn’t exist, France might have had another dictator, but not one with the military ability to conquer all of mainland Europe and implement many of the reforms of the Revolution in it.

The US Civil War could have gone very differently without Lincoln. Yes, the Union always had the industrial resources to win if they stick it out, but that’s not the same as having the wherewithal.

And it’s rather hard to argue that the internet hasn’t transformed the world. Same for the airplane. Same for the railroad. The Industrial Revolution is defining our history now.

And psychohistory is absolute bull. The one constant in historical research is that we can’t extrapolate from the past; there are far too many variables, and far too many unknowns.

Read the predictions of some of the people – including noted academics – who thought they’d developed a sweeping theory of history. They tend to be hilariously off the mark.

I’m surprised to see echoes of the Lensman series, where a crucial invention is made by a scientist who was mind-controlled by an alien as part of a plan to shape history– to create humans powerful enough to take on a opposing alien civilization.

Oh, and we’ve got a echo of Vonnegut’s The Sirens of Titan, where aliens human civilization to send a message or something.

The Wheel of Time is very much a meditation on and exploration of the Great Man Theory (like one of its significant influences, War and Peace).

WW2 seems a pretty good case for the “Biographies of Great Men” idea. If Germany had had a normal dictator, for example, history would have gone very differently.

very informative post

That seems like it must be some sort of misunderstanding, surely? Isn’t the distinguishing feature of scientific theories that they made predictions that were verified?

At least, it’s been my understanding for a long while that that’s the case. That it is always possible to come up with an idea that explains all the current data, no matter how abstruse said idea is, but that the question is whether the predictions that follow from said idea can be proven. Like the Higgs-Boson was predicted in 1964 and shown to exist in 2012.

Or do historians just work that differently from other disciplines of science?

@8 And in the epilogues of War and Peace Tolstoy has an extended discussion on the Great Man Theory, including an amusing paragraph thoroughly ridiculing it:

Annalee Newitz has a new time travel book called The Future of Another Timeline. Most of the edits that time travelers make get washed out and make no lasting changes, except for changes to one particular person. A story with both collective action and Great Man being valid.