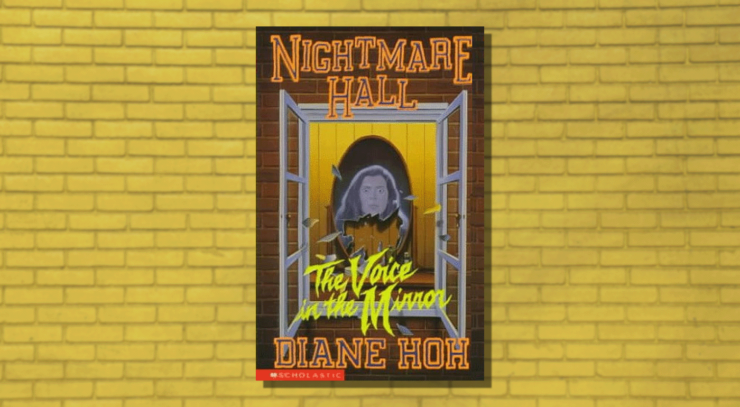

The holidays are a time for traditions and togetherness: choosing and trimming the Christmas tree, wish lists for Santa, gathering with family and friends. In Diane Hoh’s Nightmare Hall book The Voice in the Mirror (1995), the students of Salem University have ambitious plans for celebrating the season, including a fundraising performance with proceeds benefiting the local hospital’s pediatrics department and a fancy dress gala. But of course at Salem University, nothing’s ever that easy, and while the students might be dreaming of a white Christmas, they get a whole lot of blood and terror instead.

Annie Bolt is heading up the holiday planning: she’s leading the decorating committee, coordinating and starring in the fundraising holiday skit, and definitely feeling the pressure. But she has a big group of supportive friends behind her pitching in: Lisbet Wicker is a quiet girl and former swimming champion who sustained a head injury on a diving board, which sometimes messes with her short-term memory; Helene Reed is glamorous and gorgeous; and Gerrie Dunn is Annie’s roommate and a talented seamstress who is designing and making costumes for the show, including some great elf shoes. Their guy friends Quentin Andes, Lucky Sweeney, and James Polk are the muscle, student athletes who are happy to pitch in hauling trees and boxes. When Annie haggles with tree lot worker and fellow Salem U student Dix Charteris in an adversarial meet-cute, their friend group is complete. There are an even number of guys and girls, but The Voice in the Mirror refreshingly resists the urge to pair them up, for the most part: Dix quickly becomes Annie’s romantic interest, though this remains peripheral to the main action of the book. Lisbet and James are best friends, but their relationship is platonic and sibling-like. Gerrie was interested in Quentin at one point but he’s a bit aloof and was impervious to her charms. The friends like each other, support each other, and have their eye on the prize of raising a whole lot of money for the local pediatrics department, where they also volunteer once a week, hanging out with the children receiving treatment there. They’re gearing up for a holly, jolly holiday. What could go wrong?

The friends’ holiday planning starts with finding the perfect tree for the Theater Arts building and after tromping past a slew of disappointing specimens in the local tree lot, Annie finds the one she’s looking for: “an enormous snow-sprinkled fir tree standing regally in front of the lot-keeper’s shed” (3). Annie aggressively (and successfully) barters with Dix and even gets him to deliver the tree to campus, since it’s far too big for the pickup they brought to load it into. Her successful tree score and flirting with Dix have Annie feeling pretty good, and it’s overall a pleasant outing, with the exception of an argument between Helene and a mystery person, as Annie overhears Helene asking “What are you staring at? … Stop it, will you? You’re scaring me. You look like you’re staring at a ghost! Cut it out!” (7-8), but doesn’t see who she’s talking to. Annie intends to ask Helene what was going on later, but for now, there’s important tree business to attend to.

When Dix shows up at the Theater Arts building with the tree in tow, he hangs around to help with the impromptu tree-trimming party, almost effortlessly becoming a part of the group. When the tree proves too big to stand safely on its own, Dix steadies and anchors it, which is great … until Helene climbs a ladder to put the star on top and the whole thing falls over and squashes her, with Helene pinned between a box of now-broken glass ornaments beneath her and the tree on top. It must have been a heck of a tree because when the doctor at the hospital comes out to talk with Helene’s friends, she tells them that Helene is “not good, but she’s in stable condition right now. She’s got some pretty serious lacerations on her back and shoulders, couple of broken ribs, one of which punctured a lung, and a broken jaw. Some other damage to her face, which we’re not sure about yet. She’s in X-ray right now. Also has a concussion” (42). As the friends analyze what could have gone wrong, the only possible explanation seems to be that someone intentionally un-anchored the tree to take Helene out. Annie is anxious to ask Helene about who she was arguing with at the tree lot, but before the friends can circle back to the hospital to ask her the next day, Helene’s parents come and take her back to Texas to get her reconstructive surgeries and recuperate closer to home.

The group is badly shaken, but the show—or at least the fundraising skit for the pediatrics department—must go on. However, even an amateur skit isn’t safe. When the group is hauling boxes of props down from the seventh floor of the Theater Arts building, Lisbet nearly falls down the freight elevator shaft. She tells Annie that she thought she heard someone calling her name from downstairs and when she went to the shaft to look down and see who it could have been, she was overtaken by vertigo (a lingering effect of her head injury—one that would presumably keep her from standing on the precipice of high places, but apparently not). When Annie finds Lisbet and reaches out to pull her back from the edge of the elevator shaft, she sees “a foot in a green felt elf’s slipper, the toe pointed and curled upward, a small silver bell attached to the tip of the curl, slide out from behind the thick steel beam and kick Lisbet’s foot right out from underneath her” (89-90). There are a tense few minutes where Lisbet hangs on for dear life while Annie puts together a daring rescue plan, but she’s able to save her friend. Just like the tree that was set up to fall on Helene, that jaunty elf boot that kicked Lisbet off balance definitely speaks to premeditation and clear intent, though there aren’t any further clues as to who’s doing this or why. Annie worries that campus safety will think she’s lost her mind if she tells them that her friend was nearly killed by an elf and she’s right (though with all the weird things that happen at Salem University, maybe they should suspend their disbelief just a little).

The friends take a break and decide to get some fresh air the next day by going sledding at the local state park, zipping down a snowy hill on innertubes and making a snowman. Lisbet isn’t particularly worried about her would-be murderer, though Annie insists that someone stays with Lisbet at all times, just in case the mystery elf comes back to try to finish her off. While Dix goes to warm up the car, James decides to take one last run down the hill, even though it’s getting dark and after some hesitation, Lisbet decides that’s a pretty good idea and follows after, despite Annie’s objections. James comes trudging back up the hill a few minutes later, but Lisbet never does. Everyone is scattered—starting the car, getting coffee, sledding down the hill—and no one has an alibi. They also only have one flashlight, which limits their search and before long, both a park search team and an ambulance are on-site and their hopes of finding Lisbet unharmed are waning. As the group splits up to search, Annie and Dix find Lisbet strangled with her scarf and buried in a hole in the ground, covered by a board and thick layer of fluffy snow. She’s not breathing when they find her, but Dix starts CPR and the paramedics are quick to get on the scene; they get Lisbet breathing again and rush her to the hospital, where she tells them that she can’t remember anything after sledding down the hill. She has bouts of short-term memory loss as the result of her diving-related head injury and whatever happened to her between the bottom of the hill and the hole they found her in has disappeared into that void.

As these near-death experiences pile up, the group stays focused on the skit—after all, the kids are counting on them. The fake reindeer that pull Santa’s sleigh pose an odd threat of their own, because while the reindeer themselves are harmless plastic, their antlers are sharp as knives (which seems like a major design flaw and safety hazard). Annie is the skit’s Santa and Dix has worked on a harness that will allow Annie to fly through the air above the stage when she makes her big entrance, though being suspended high in the air seems like a terrible idea when you know someone is actively trying to hurt (or maybe even kill) you, and it is. The night of the show, the cables snap one by one, sending Annie plummeting to the stage, where she slices her arm open on one of the razor sharp reindeer antlers and the group is headed back to the hospital again. (One of Annie’s first questions on regaining consciousness is whether or not they had to return everyone’s money, but it turns out that in the aftermath of this horrific accident, people gave even MORE money to the pediatrics fundraiser and Gerrie assures her that they made “enough to make a really nice holiday for the kids” [183], so at least there’s that).

As the mystery unravels, the interconnections of past and present violence emerge, with the attacker (kind of) visited by a ghost from his past. Hoh punctuates The Voice in the Mirror with chapters told from a first-person perspective by the character who is committing these acts against his friends (though his identity remains a mystery until the final chapters). Conflicted and terrified in his dorm room, he begins to hear a voice from the mirror, berating him and badgering him into further violence. As he looks into the mirror, he sees just “Me, but different. No sickly pallor, no beads of sweat, no trapped-animal eyes … Me as I’m supposed to look, as I would look now if I hadn’t been shocked senseless” (16-7). As the voice in the mirror reminds him, the horror all goes back to Elyse Weldon, one of his high school classmates who got the scholarship that was his only ticket out of a future working a dead-end factory job. He tried to talk Elyse into giving up the scholarship (which would then presumably come to him as the second-place contender) and when she laughed in his face, he bludgeoned her skull with a trophy and pushed her car into a nearby quarry. But now she’s back and looking for revenge—or at least that’s what his hallucinations and the voice in the mirror are telling him. First Helene’s face transforms into Elyse’s, then Lisbet’s does, and finally, Annie’s, with these girls taking on the appearance of his dead enemy and darkest secret, motivating his violence against each of them in turn.

It’s tough to figure out who the attempted murderer is, because the majority of the group is at Salem University on either an academic or athletic scholarship, and for many of them, that scholarship is their ticket to social mobility, to create a new life for themselves that takes them away from the poverty and limited options of their families and hometowns. For the young men specifically, there’s pressure to come home, work, and help support the families; their families aren’t supportive of their choice to go to college, the students are paying their own way, and the only reason they’re able to do so is because of their scholarships. Without the scholarships, they won’t be able to stay in school and they’ll lose it all. There is intense pressure to perform—with high grades, competitive athletic performance, or both—and there is no margin for error.

In the final confrontation, the attempted murderer sneaks up on Annie while she’s repacking the skit props, bundles her into a box with one of the dangerous reindeer, and prepares to push the box down the freight elevator shaft. It’s a long push from the dance studio where Annie was working to the elevator shaft, which gives him time to explain why he’s doing what he’s doing, both in his own voice and in the voice from the mirror, with the two personas bickering among themselves as they monologue to Annie. As he explains “I needed that scholarship, Elyse. You didn’t … I had to take it away from you, or my life would have been over. Stuck in a factory like my old man, dragging out of bed every morning at the crack of dawn to go to work in that hellhole, until one day when you’ve got a wife and six kids, they fire you for no reason, no good reason at all. Then you’ve got less than nothing … Do you really think I could ever, ever live like that?” (209, emphasis original). Annie keeps trying to reason with him, telling him over and over that she’s NOT Elyse and doesn’t even know anyone named Elyse, but it doesn’t slow him down. She uses one of those razor sharp reindeer antlers to cut herself out of the box, only to find herself right at the edge of the elevator shaft and face-to-face with a deranged Quentin.

Annie fends Quentin off by stabbing him in the chest with the antler—but after that there’s little resolution. Aside from Quentin’s monologue and his conversations with the voice in the mirror, we don’t learn anymore about his background, his hometown, or Elyse’s murder. With so many other characters coming from a similar background and facing similar struggles, Annie really thought it could have been just about any of them. The only explanation she comes up with is that there’s something fundamentally “wrong” with Quentin, though there were no warning signs in his day-to-day interactions with his friends, or publicly worrying behavior. The only clues are the altercation when Quentin is staring fixedly at Helene at the tree farm (though no one takes much note of this) and a conversation between Quentin and Annie when he tells her that he overheard James talking to himself in their room in two different voices (a ploy to throw suspicion off of himself and maybe a cry for help), asking her whether she thinks James ought to see a psychiatrist, a concern that Annie shrugs off, and then second guesses herself for later. As Dix reflects in the book’s closing pages, “No wonder no one could come up with a motive … No one knew Quentin was seeing a ghost everywhere he looked. There really wasn’t any motive that made sense, which was what everyone was looking for” (226). Desperation and guilt seem to have been Quentin’s motives, but no one knew him well enough to realize they were there, even when he was surrounded by friends.

The holiday season at Salem University ends happily enough: the tree is back up, the blood is cleaned up, and the holiday gala goes off without a hitch, with Annie and Dix dancing the night away, determined to put the horror of the holidays behind them. They’ve certainly earned the right to a good time, but as they dance in the glow of the twinkling lights, the systemic class issues that motivated Quentin remain unaddressed and those super sharp reindeer antlers are packed away in storage, just waiting to slice someone again next year.