Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern— Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

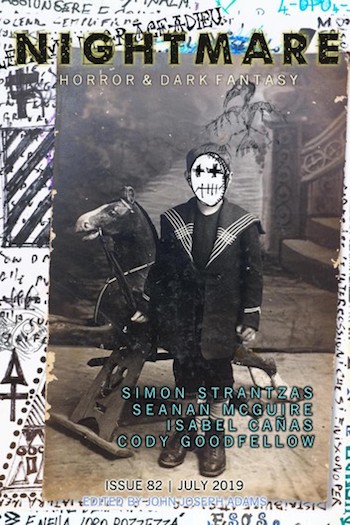

This week, we’re reading Simon Strantzas’s “Antripuu,” first published in the July 2019 issue of Nightmare Magazine. Spoilers ahead.

“There are four of us left huddled in the cabin…”

Unnamed narrator and friends Kyle and Jerry left their jobs at a socket company at the same time, but narrator hasn’t landed on his feet like the other two. [NOTE: Per my reading of this story, the narrator’s sex is left unstated. I have chosen he/him/his for my summary and comments. –AMP] In fact, he’s sunk into a depression so noticeable Kyle suggests they ditch their usual bar-hopping for time outdoors. Kyle’s tall, outgoing, and confident. Jerry’s his opposite, maybe tries too hard for detachment. They’re both good people, which narrator needs in his life right now.

They hike into Iceteau Forest. The promised sunny weather lasts one day, followed by downpours. They slog on through old growth groves; narrator, whose sense of well-being left with the sun, senses something’s wrong. Just his depression? No—among the trees, he sees a giant creature unfurl itself. He screams. The others see it too: a specter twenty feet tall but only a hand’s breadth wide, with elongated stick-insect limbs and no head, only a too-wide mouth and rows of sharp teeth embedded in undulating flesh.

It reaches for them. They flee, pursued by the crash of uprooted trees and the creature’s wind-howl voice. Kyle spots a ramshackle cabin, and they tumble inside. Narrator curls against the door; all stare at “the cabin’s buckling walls, its trembling windows, waiting for the defenses to inevitably fail.” Somehow the commotion subsides. The creature has retreated into the woods, waiting.

They’re not alone in their misery—in the bedroom crouch fellow hikers Carina and Weston. Carina is whimpering the name “Antripuu,” though she later denies it. The five share sleeping bags that night; narrator’s so exhausted even terror can’t keep him awake. In the morning he joins Carina at a window and notices six black metal rods encircling the cabin, chains leading from their tops down into the mud. Narrator asks whether they have anything to do with… Antripuu. Carina shudders, then confesses that her grandmother from the “old country” told her about Antripuu, a forest spirit or elemental. Just a story, nothing real.

Weston thinks they suffered a shared delusion, and insists on going to find help. Clouds still darken the sky, mist hovers over the ground; Weston strides jauntily to the edge of the forest, where he turns to wave goodbye. From the mist behind him rises the Antripuu. With a roar like the wind, it swallows Weston whole.

The four survivors huddle in the cabin. Overwhelmed by their situation, narrator’s tempted to follow Weston. Carina slaps him, bringing him back to his senses.

They argue: Jerry wants to wait out the storm, but hasn’t Carina named Antripuu a storm-bringer, won’t the deluge linger as long as it does? Besides, they’re almost out of food. At last Kyle convinces them to run for it. If they stick together, they’ll have a chance. Besides, if they lose hope, they’re good as dead.

Their plan’s necessarily simple. They’ll move in a cluster, watching in all directions, Kyle leading. He’s dressed in everything red they can scrounge, the beacon they’ll follow if the Antripuu attacks. Passing the metal rods, narrator notices the attached chains lead to metal collars and yellowed bones he desperately hopes aren’t human.

Outside the storm is deafening, isolating the survivors even in their tight formation. Narrator feels all his life’s failures have led him to this place—he’s long suspected “something out there” wants to destroy him, and here it is, reality after all.

Someone screams. Kyle bolts, and narrator scrambles after his red-clad blur, praying Jerry and Carina are following. Narrator loses sight of Kyle, runs until he drops with exhaustion. He’s convinced the others are gone. He has only a vague idea where the road and their cars are. Recovered, he starts moving again. Without hope, nothing’s left.

He glimpses elusive red—Kyle—dashes after through skin-raking branches. Everything in Iceteau Forest is hungry for his blood, including the ravine that suddenly opens underfoot. Narrator falls into the stream below, breaking an arm. But above he sees red, reaching down for him. He tries to grab the rescuing arm, then realizes it’s overlong, the Antripuu’s stick-insect limb tangled with the tatters of Kyle’s clothing. Narrator cowers, and the ravine-straddling Antripuu grinds its teeth in frustration against the rocky rim. Narrator screams up at it: What has he done to deserve this malice, to be “chased by a spirit or god or figment of my imagination until my body is destroyed and I have no choice left but to curl up and die?”

The Antripuu’s only answer is its ravenous storm-howl, but narrator hears a smaller, higher-pitched voice: Carina. She creeps close to the ravine and urges narrator to move. When the Antripuu circles out of sight, he struggles downstream until the ravine sides taper down enough for her to pull him out.

She fashions a rough splint for his arm, harries him onward. The storm gradually peters out as they walk through Iceteau Forest. Narrator hopes Kyle and Jerry escaped, hopes they’ve gotten out to the car, hopes they’re looking for him and Carina.

He hopes, and Carina tells him stories about her grandmother and the old country, good as well as bad. He starts to understand that the good stories can make you forget about the bad stories even if you only want to believe in the bad. Finally narrator hears a car engine in the distance. Or maybe it’s the wind? Hard to be sure, but—

All he can do is hope.

What’s Cyclopean: Words are repeated like a chorus: illusion, hope, story.

The Degenerate Dutch: Five people trapped in a cabin with a monster outside could easily fall into horror movie stereotypes, but—aside from Carina making a worthy final girl—manage to generally avoid it. Even the overconfident jock goes to peace rallies.

Mythos Making: The abyss has teeth today.

Libronomicon: If our heroes had any books with them, they’d have long since gotten sopping wet.

Madness Takes Its Toll: “Antripuu” has a thoroughly modern sensibility around mental illness, with Narrator’s depression and Carina’s anxiety playing key roles. Maybe that’s why Narrator seems so sensitive to the idea of delusions, or the possibility that Weston’s maniacal laugh indicates something beyond simple stress.

Anne’s Commentary

In a Nightmare Magazine interview with Sandra Odell, Simon Strantzas discusses his desire for horror fiction “purer and more direct” than what he’s been writing lately. He categorizes horror as falling into investigation stories and experience stories; he’s usually drawn to the former narrative structure, but with “Antripuu” he chose to focus on “the experience of merely surviving an unnatural encounter.” In other words, he was after the most primal of terrors: running like all holy hell away from a FREAKING MONSTER. Deep in an ancient forest. On a dark and stormy day-into-night.

The forest might alternatively have been a cave or mountaintop, desert or ocean waste—isolation and wildness are the key features for monster-enhancing settings. Rainstorms and mud might have been blizzards and ice or simooms and blistering sand—the raw power of nature abetting the supernatural threat, or (scarier still) caused by the supernatural threat. Want to further heighten the tension? Add some work of human ingenuity that’s supposed to protect us, here the cabin, and show it to be inadequate—the too-flimsy cabin could also have been a proud fortress or a fence, a magic spell or an antibiotic, a fast car or a tank, a wooden stake or a shotgun or an atomic bomb.

But the core ingredients of any “unnatural encounter” story are the MONSTER and the PEOPLE, IT versus US. You can start with the monster and then supply it with people to harass, or you can start with the people and then customize a monster to play to their deepest fears. Or, even more fun, a monster that plays to both their deepest fears and their deepest desires.

I think Strantzas has gone for the people first, then the monster. More fun, he’s gone for the monster playing to both fear and desire, clinched in a deep-psyche embrace. More or less fun, depending on the reader’s bent, he’s provided a psychological weapon to break that lethal compound-impulse. You couldn’t have missed it. It’s the thing with feathers that perches in the soul. It’s Rhode Island’s state motto. It’s a pretty good girl’s name.

Hope, that’s right. We’re good as dead without it, according to tall and confident Kyle. Too bad hope is what our narrator’s lost long ago.

Makes sense, because Narrator’s defining trait is his depression. It’s really bad these days, but from narrator’s internal monologue, he’s been chronically depressed. Something, he suspects, is out to get him, and worse, it’s for no good reason.

Or worst, maybe he deserves it. So what’s to hope for?

Poor narrator, always wanting to believe in the bad stories. Could be the reason you were the first to see the Antripuu is because you created it from the sheer force of your screwed up psyche and life. Except didn’t Carina and Weston encounter it before you and your friends? Maybe Carina created it out of her chronic anxiety and Grandmother’s old world tales. Maybe the two of you created it. Yeah, you do make a great pair.

Or maybe, just maybe, the Antripuu really is real, its own thing rather than a materialized projection of narrator’s state of mind. It needn’t be an either/or, though. The Antripuu can be real AND narrator can project onto it his cherished paranoias and dark longings.

Look at it.

One could envision ravenous malice as an enormously fat creature, bloated by its gluttony. That’s scary. However, Strantzas has gone to the other (I think) even more effective extreme. He’s made the Antripuu bizarrely thin for its giant’s height, a hand’s breadth wide, what, six inches or less! Its limbs are overlong and insect-spindly. Why, it’s so emaciated, so starved down, it doesn’t even have a head.

However, it has a proper monster’s most terrifying feature: a maw, the better to eat you with, my dear. Narrator describes Antripuu’s mouth without Lovecraft’s taxonomist’s detail, but he says enough to spark the reader’s imagination. I mean, don’t you have to figure out what a crazily wide mouth atop a stick must look like? My first dazed thought was of a Cheshire Cat’s smile balanced on a birch tree with its canopy cut off. I’ve progressed to an insect-tree with an upper terminus that opens out into a circular mouth like a lamprey’s, only sufficiently expandable to engulf and grind up tents and footballish hunks.

The Antripuu can eat whatever it wants, but it remains thin. Which implies it must always be hungry. Insatiable, like the Iceteau Forest itself. By projection, it perfectly represents narrator’s greatest fears: First, that the world’s intent on destroying him; second, that he has brought destruction on himself, sui maxima culpa. Hopeless against it either way, narrator must die.

Except he gives way to a rage that undermines his depressive guilt—whatever he’s done, he can’t deserve the Antripuu! Then Carina shows up, perseverant hope personified, to harry narrator to his maybe-salvation.

Rats, no space to speculate about those metal rods and chains and bony remains, the story’s most intriguing unexplained detail. Or the Wendigo parallels. Take it, people!

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Horror can offer good, shivery fun as Halloween approaches, but it also asks questions. The most common may be “What should we fear?” Lovecraft’s standard answer was “everything,” and also “things beyond human understanding”—he shows up in friends’ stories expostulating on the vitality of imagining new fears, describing the indescribable. Other authors get a frisson from making the familiar or the beloved terrifying: your house, your kids, your own skeleton.

But there are other questions—and I confess to being particularly interested in “How should we react to terrifying things?” It’s an awkward question, because some answers shift your genre entirely. If you stop freaking out about ancient pre-human civilizations and get on with your groundbreaking archaeology, you aren’t in the land of horror any more. “Antripuu” finds safer territory (in a manner of speaking) by giving us a monster unambiguously terrifying. Giant insects with void-mouths for heads? Yes, you definitely should be afraid of supernatural top predators that want you for lunch. It’s a common enough answer to the first question that attempts at originality quickly get into silly territory. Killer tomatoes, anyone?

The Antripuu is at no risk of being silly.

But there’s more to fear here getting eaten. It’s the whole world of powers that want to chew you up and spit you out—horrible jobs, relationships gone bad, all the giant incomprehensible horrors of modern life. I love that the monster here isn’t so much a symbol of all these things—I think it’s itself, a real spirit or animal that can be frustrated by a crevasse—but the last straw on top of them, an impossible thing that they lead to naturally and inexorably. After all life’s other disappointments, why not void-mouths?

And that “why not” is the real horror of “Antripuu.” Narrator’s depression, Carina’s anxiety, are monsters they’ve already spent years fighting. Monsters that maybe make them vulnerable to the supernatural monster—but maybe also give them practice for surviving something that powerful and hungry. Something that seems at the same time meaningless and to carry all the meaning in the world.

Narrator demands, at one point, to know what they’ve done to deserve this. It’s another set of questions to which horror is well-suited. Do we deserve the terrible things that happen to us? Is it better to deserve them (and live in a universe where you control your own fate, but can screw it up beyond repair)? Or is it better to be blameless (and live in a universe where terrible things can happen to everyone, regardless of their choices)? Cosmic horror—not the Derlethian heresy, but the raw stuff—falls firmly on the latter side. “Antripuu” is more ambivalent. Does despair call the monster, or give it an opening once it’s there, or just make the experience of being chased by a giant voidmouth even worse?

On a gentler note, I couldn’t help trying to map the setting, despite thinking its fictive uncertainty was the best narrative choice. (We’ve all seen how awkward it can get when authors borrow real mythical monsters sans original contexts.) I don’t have any particular hypotheses about Carina’s “old country,” but suspect that the Iceteau forest is found in northern Michigan or the bordering bits of Canada. The terrain is right, and the name is the sort of hybrid you get from Anglo colonists chatting with French trappers. And it’s certainly an area that makes for good hiking country—but a very bad place to lose track of your car.

Next week we’ll cover F. Marion Crawford’s “The Screaming Skull,” mostly because Ruthanna has been reading Vivian Shaw’s Grave Importance which has the most adorable baby screaming skulls infesting old houses. We have a feeling that Crawford’s version is not so adorable. You can find it in The Weird.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is now available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.