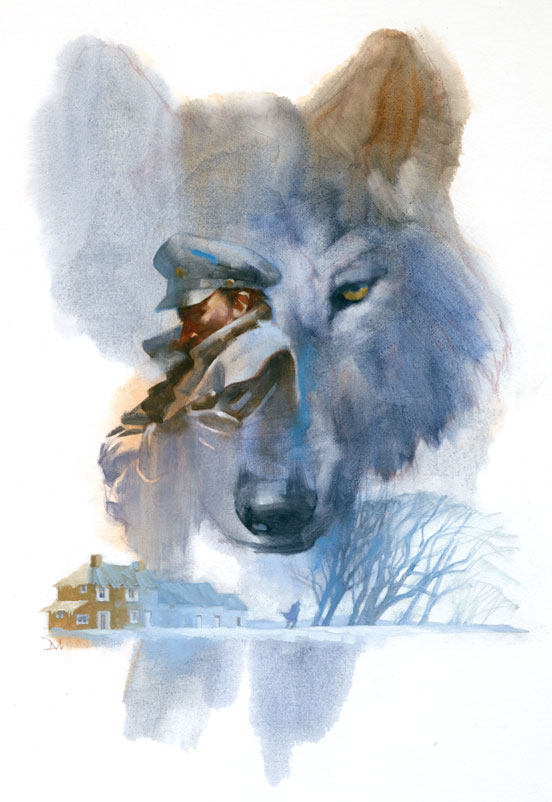

The fourth in Hugo and Nebula Award-winning Michael Swanwick’s “Mongolian Wizard” series of tales set in an alternate fin de siècle Europe shot through with magic, mystery, and intrigue.

This short story was acquired and edited for Tor.com by senior editor Patrick Nielsen Hayden.

“Have you ever killed a man?” the vagrant asked.

“That is not something we discuss,” his companion replied.

“I myself have killed five. That is not many. But two I killed with my bare hands, which, I assure you, is not easy.”

“I am sure that it is not.”

“Don’t you know?”

The second vagrant said nothing. They both continued trudging across the frozen German countryside. Winter had been almost as hard on the lands hereabout as the war had been to the lands to the east. It had buckled roads and destroyed bridges and collapsed roofs, and if there were any leavings to be gleaned in the fields they were buried under sheets of ice. The stubble crunched like glass underfoot making the going difficult. But the main routes were all choked with refugees and since the vagrants were headed in the opposite direction, toward the front, to use them would only draw attention to themselves.

“Ritter?” the first vagrant said.

“Mmm?”

“Do you remember our instructions?”

Ritter stopped. “Of course I do,” he said. “Don’t you?”

“Oh, I remember them. I just don’t believe in them anymore. We’ve been walking so long that all my life seems like a dream to me now. Sometimes I cannot even remember our destination.” When Ritter said nothing, his companion turned away. “But let’s not stand out here in the open, waiting for the Cossacks to discover us.”

They resumed walking. A leafless tree rose up in the distance, crept slowly toward them, was a brief respite from the monotonously unchanging fields, and then dwindled away to their rear. “Ritter?”

“Eh?”

“I address you by name, the way a true comrade does. Why do you never do the same for me?”

Again Ritter stopped. “That is a good question,” he said. “A very good question indeed.” Anger entered his voice. “Let me ask you some of my own. Why do you not know our mission or our destination or even your own name? Why is everything so silent and still? Why are my legs not weary from all this walking? Why does the sky look so much like a plaster ceiling? Why can I not make out the features of your face? Why are you neither tall nor short, nor thin nor fat, nor ruddy nor pale? Exactly who are you and just what game are you playing with me?”

You should never have used the word “dream,” a woman’s voice said.

That wasn’t it. When I tried to find out who his companion was, something told him I was an imposter.

In any case, this session is done.

Everything went black.

When Ritter awoke, he found himself lying under a feather bolster in a bedroom with yellow walls and green trim, a flowered jug atop a washstand, and a winter landscape outside the curtained window. A short man with the broadest shoulders he had ever seen on a human being stood looking out that window, hands clasped behind his back. An old woman sat in a wooden chair, embroidery loop in hand, sewing tight little stitches with a sharp tug at the end of each. “Where am I?” Ritter said. His head felt thick and dull.

“Someplace safe.” The man turned, smiling. He had a round, benevolent face. To see him was to want to trust him. “Among friends.”

“Ah.” Ritter’s heart sank. “I see.” He closed his eyes. “At least I made it through the front lines.”

“Too bad for you that you did,” the old woman said. “We have already determined that you are in the pay of the British Secret Service. Your presence here in civilian clothing is by itself enough to justify your execution as a foreign spy.”

With a touch of asperity, Ritter said, “I am a German citizen in Austro-German-Bavarian territory. It is my right to be in my own country.”

The man shook his head in gentle reprimand. “The land you were born into ceased to exist weeks ago. Legally, you are a nationalist partisan in the westernmost provinces of the Mongolian Empire. But we are getting off on the wrong foot. Let us start over. Dr. Nergüi and I are alienists. We have begun a program of dream therapy intended first to obtain information from you, then to use that information to cure you of your unthinking loyalty to an anachronistic and dysfunctional regime, and finally to convert you wholeheartedly to our cause.”

“That is not possible,” Ritter said with conviction.

“Think of Borsuk and me as dam-busters,” Dr. Nergüi said. “We drill and we drill with no discernable results until at last our labor produces a single drop of water. Shortly after that, another follows, and another, and before you know it, the wall bursts open and the lake that the dam has been holding back explodes outward, inundating all before it.”

“But that’s enough chatter for now.” Borsuk patted Ritter’s shoulder. “Go to sleep, my friend. We have hard work before us. Very hard indeed.”

All against his will, Ritter felt himself tumbling down into the darkness, into the depths of sleep. Somewhere far, far away in the forests of the night, he thought he sensed someone or something searching for him. Somehow that seemed important.

In his dreams, Ritter was standing in Sir Tobias Gracchus Willoughby-Quirke’s classically austere, oak-paneled office. Arrayed on the desk between them were the clothing and accoutrements of an indigent.

Sir Toby waved a hand at the ragged clothing. “Everything you see here is convincingly shabby, and yet serviceable as well. The coat is good, dense wool—even the patches. Soaking wet, it will keep you warm. The shoes look decrepit but are cut to the measure of your feet. They have been waterproofed with candle wax, as a hobo might do. Inside the laces are lengths of pianoforte wire suitable for making snares or garrotes. It would be suspicious for you to carry a gun. However, you will have this.” He picked up what looked to be a common kitchen knife. “Sheffield steel. Antique but sharp. The wooden handle is broken and taped together with strips of linen in a manner that looks makeshift. Yet in a fight, you may rely on it.”

“I see that I have some rough traveling ahead of me,” Ritter said. “Where exactly do you wish me to go?”

“I am sending you and your partner to the Continent, behind enemy lines. You will rendezvous there with a member of the resistance who has important information to share with us.” Sir Toby presented an envelope and Ritter, feeling a strange, sourceless reluctance, opened it and read. It contained a name, an address, and a date. That was all.

“Is that all?”

Sir Toby took back the envelope. “I am reluctant to give you more than an absolute minimum of information, lest you be captured.”

“I will not be captured. But if I am, I am confident that I shall escape.”

“Oh?” Sir Toby placed his hands on the desk and leaned forward. His eyes gleamed. “How?”

Astonished, Ritter said, “You know how. My— ” He looked around the office, at the walls that swelled and snapped like canvas in the wind, at the bust of the archmage Roger Bacon in the tympanum over the door that leered and winked at him, at the inkwell that went tumbling in the air without spilling a drop of its contents. It all felt wrong. Even Sir Toby himself seemed an unconvincing scrim over some darker and truer version of reality. Ritter’s head ached. It was hard to think logically. “Or do you?”

“Let’s say that I don’t. Purely as a sort of exercise. It’s your partner, isn’t it? You’re counting on him to rescue you.” Sir Toby smiled in a way that was avuncular, predatory, insincere. “Aren’t you, son?”

Convulsively, Ritter swept his hand over the desk, sending clothes, shoes, knife, and all flying in all directions. “You are not my father. Nor are you the man you pretend to be. Clearly, you are part of a conspiracy of some kind. Well, it won’t work! You’ll get nothing out of me!”

Excellent work. I shall return him to consciousness now.

“You see how easy that was?” Borsuk said. “Dr. Nergüi put you under and I guided your thoughts, and now we know your mission, the name by which your contact will identify himself, and where and when he may be captured. All that remains to be discovered is the identity of your oh-so-mysterious partner.”

“Do you still think you will not break?” Dr. Nergüi asked.

When Ritter did not reply, she picked up her embroidery and set to sewing again.

For a long time, Ritter lay in the bed, eyes closed, listening to the scratch of a goose-quill pen—Borsuk writing up his findings, no doubt. The rest of the house was uncannily quiet. He could hear small creaks and groans as boards shifted slightly. But no voices, no footfalls, not the least indication that, save for the inhabitants of this room, the house was occupied. Finally, he said, “So it is just you two here? No orderlies or guards?”

Abrupt silence. Then Borsuk said, “This one’s an optimist, Dr. Nergüi. Even in extremis, this clever young man probes for information, tries to seek out our weaknesses, makes plans for escape.” He sounded almost proud of Ritter.

“There is a war going on, in case you haven’t noticed,” Dr. Nergüi said. “Resources are stretched thin. We must make do with what we have. But if you think the two of us are not up to the task . . .” She produced the knife that Sir Toby had given Ritter and placed it on the nightstand. “Sit up.”

Ritter did.

“Now pick up the knife.”

He tried. But whenever Ritter made to close his fingers about the hilt, his hand turned out to be above or below the knife, clenching empty air. Again and again he tried, with the same maddening lack of results.

Drily, Dr. Nergüi said, “So you see now that it is useless to try to escape.”

“I see that you are glamour-workers with a mountebank’s talent for illusion. But I still have my indomitable Teutonic will, thank God. You may kill me if you wish, but your tuppenny magics cannot make me do your bidding.”

In an off-handed manner (for he still continued to write), Borsuk said, “Of all the talents, that of illusion has always been thought the weakest. Oh, we could walk you off a cliff or show you the dead face of whomever you loved most and convince you it was your own doing—for a time. But we could not set a forest ablaze the way a pyromancer can, nor cripple a man with frostbite like an ice wizard. Our magic wears off and thus it was never greatly valued.

“But then it was realized that, all magic deriving from the powers of the mind, illusion was the very key to its source. In her homeland, Dr. Nergüi is considered a very great woman for her discoveries. You should be proud to have her devoted to your case.” Borsuk sprinkled sand over his writing and shook it off again. “Your contact lives not an hour’s walk from here. The messenger who will carry this report”—he rattled the parchment—“to Military Intelligence is not expected until tomorrow morning. If only you were free, you could warn your contact, get his information, and snatch success from the embers of failure.”

For a single heartbeat, hope leapt up within Ritter’s breast. Then he said, “You taunt me.”

“Perhaps I do. Get dressed. Your clothes are in the armoire. No need to be shy before Dr. Nergüi, she’s a grandmother—”

“Great-grandmother.”

“Great-grandmother, and she’s seen it all before. Your boots are under the bed. Make sure to wear two pairs of socks—it’s cold out there.”

Wondering, Ritter did as he was told.

“Now, leave.”

The bedroom opened into a homely parlor room, washed in grey winter light. His mud-stained greatcoat hung on a peg by the door. Ritter donned it. He went outside and stood blinking on the stoop. The frozen fields he remembered so vividly from his dream or hallucination stretched toward a wood that was clearly miles away, a mere line in the distance. He took a few hesitant steps in its direction and then looked back at the building he had just left. A sign over the door read САНАТОРИЙ. Sanitarium. That was the only indication that his prison was anything other than a farmhouse.

Turning his face to the horizon, Ritter began to walk, expecting with every step a shout from behind, followed by a bullet in the back. Inexplicably, this did not happen. Field-stubble crunching underfoot, he broke into a clumsy run. Other than the lazy cawing of faraway crows, his footfalls and the rasp of his breath were the only sounds.

It was not possible that they would simply release him.

Was it?

The trees were all but unreachable. But if he could make his way to them, he had the barest chance of escape. He ran and as he ran the cold air cleared his head. The mental fog lifted at last, revealing a variety of pains that had been hiding beneath it. He was obviously heavily bruised on his legs, shoulders, and buttocks, and his ribs ached like blazes. The result of a beating he had received when he had been caught, no doubt. He vaguely recalled killing one of the enemy soldiers before being subdued. It was a miracle he was still alive.

So, no, they would not simply release him. Not when he had killed one of their own.

And yet . . . the farmhouse sank to nothing behind him. Winded, he slowed to a walk. Several times he tripped and caught himself, and once he fell flat on the rock-hard ground and briefly thought he had sprained an ankle but was able to walk it off.

He looked over his shoulder. The farmhouse had been swallowed up by the billowing farmlands and still nobody but he was in the fields. Why was he not pursued?

It made no sense.

Unless he was being observed from afar, by means either magical or natural. It was the only rational answer he could think of. Which was why he refrained from reaching out with his mind in search of Freki. If he was being watched or, worse, lying abed hallucinating, he did not want to hand his interrogators the information which, after the name and location of his contact, they desired most: the knowledge that he was a member of the Werewolf Corps and that his traveling companion was a wolf. So, much as he would have liked to coordinate his escape with Freki, he dared not make the attempt.

Ritter was trained to use his wolf as a weapon. With Freki at his side, he was a match for ten conventionally armed men. A vagabond traveling in the company of a wolf, however, was a memorable sight. So they had journeyed separately, Ritter on the roads and his partner keeping to the ditches and coverts, with anywhere from half a mile to a mile’s distance between them. As a result, Freki had not been able to help when Ritter was caught by (he remembered the incident now) an unexpected patrol of foragers, looking to complement their rations with a stolen hen or flitch of bacon extorted from the locals.

If only he had not lost his temper and killed that soldier! They would not have seen that he fought like a military man and might well have left him, beaten but alive, where they’d found him.

Or maybe not. Their sergeant had acted like one with the second sight. Those with a touch of talent often wound up as non-commissioned officers or better. In wartime, such men were drawn to the military, where they might rise through the ranks even though they were far from gentle-born.

Ritter’s feet were damnably cold by now and his hands as well. There had been a mismatched pair of gloves in the pockets of his greatcoat. But they had been emptied out, along with his knife, matchbox, pipe and tobacco pouch, and a small sack of parched grains intended to stave off hunger. So he pulled in his arms from the coat’s sleeves, stuck them in his armpits, and kept on walking. And walking.

Hours passed and the distant line of trees did not seem to be appreciably closer than it had ever been. But there was a farm building ahead with a blue curl of smoke rising from its chimney. Ritter debated whether to bypass it entirely or to stop and see if he could trade some labor ostensibly for food but in actuality for information. Farmers, in their isolation, were more gossip-prone than most people realized. It was even possible—barely—that he would have the opportunity to steal a horse.

These were cheering thoughts. Yet the closer he came to the building, the greater his unease grew. The place looked . . . familiar.

With sinking spirits, Ritter approached the farmhouse.

There was a sign over the door.

САНАТОРИЙ.

He was back where he’d begun.

For an instant, Ritter almost lost all hope. But then he squared his shoulders, turned ninety degrees, and started walking again. As an officer and a Prussian gentleman, he could not give in to despair.

The sun through the clouds cast the faintest of shadows. He kept it resolutely to his left and lined up unprepossessing landmarks in the middle distance, a rock, a frozen clod of dirt, a dead plant sticking up out of the snow. He concentrated on making his measurements as accurate as possible. Every now and again he stopped and looked behind himself to see his footprints stretching straight and unwavering toward the horizon. Until finally his legs buckled underneath him and he sank to his knees in the frozen field.

A door opened nearby.

“Well?” Dr. Nergüi said from the stoop of the sanitarium. “Are you convinced yet?”

Wearily, Ritter looked up at her and then to one side and the other. A path of sorts had been trod into the icy ground. It bent inward to each side of the building. He had been walking around and around the farmhouse all day.

Then Borsuk was helping him to his feet and leading him inside. It was warm there. Gratefully, he felt the weight of his greatcoat removed from his shoulders. Borsuk eased Ritter onto a couch. Then he sat down in an overstuffed chair and said, “We are going to try something different now. Would you prefer we talk about your mother or your sex life?”

Dr. Nergüi held up a hand. “Look at him. He remains defiant.”

Borsuk’s face grew very still. Then he said, “Remarkable. He still hopes to escape.”

“There is a thin line between hope and delusion. In my professional judgment, our patient would benefit from having a glimpse of his future.”

“I concur,” Borsuk said.

In a ramshackle boarding house in Miller’s Court in Whitechapel, Ritter sat on the bed that was his room’s only furniture, pulling off his boots. He feared he had caught a fungus. The skin between his toes was white as corpse-flesh and a horrid stench rose up when he peeled away the socks. Not much to be done about that. The tips of several toes were black with frostbite. With the point of his knife, he pricked each of them. Three had no sensation. There were blisters too, but best to leave them alone. Punctured, they could get infected.

Not that he expected to live long enough for that to happen.

The guards at Government House had turned Ritter away when he tried to see Sir Toby. But he had expected that. Weeks of hard living had transformed him completely. He no longer looked like the sort of man who might have business with the Office of Intelligence. Even their underworld informers dressed better than he.

Ritter held up his candle stub and, waving it back and forth, was able to locate a nail in the wall by the motion of its shadow. He hung one of his socks on it to air. Then, when he could not find another nail, he draped the second sock over the first.

He lay down on the bed and tried to think. But his head was a buzz of conflicting voices. How long had it been since he had slept? His limbs were as restless as they were weary. His fingers twitched and every time he closed his eyes they flew open again.

Down deep, all men hate their fathers.

Concentrate, damn it! There was no point in going to Sir Toby’s club—even when he had looked the part of an officer, he would not have been allowed in without the company of a member. So he would have to find the man in the streets, going to or coming from his office. Ritter had to deliver his message to Sir Toby in person. It could not be given to anyone else. That was imperative.

Ritter thrashed from side to side but could find no comfort. He sat up convulsively and wrapped his arms around his stomach.

He thinks that sleep will restore him.

A guilty conscience, even in repose, knows no rest.

Throwing back his head, Ritter ran his fingers through greasy, tangled locks. Not half an hour ago, he had paid the last few coins he had for this room, hoping that some rest would clear his thoughts. It was money wasted. He couldn’t lie still for a single moment, much less for long enough to nod off.

With a groan, he sat up and began pulling on his boots again. His socks he left hanging on the wall.

By the time he’d made his way to Charing Cross, it was twilight.

The streets glistened from a rain which that Ritter could not remember, though his coat was damp from it. He faded back into the shadows, watching the carriages clatter by, eyes cocked for one in particular. A coach which rarely took the same route two days in a row, out of Sir Toby’s natural reluctance to make himself an easy target for assassins. So there was no way of being sure Ritter would see it tonight. Still . . . there were only so many ways of getting from the one place to the other. And there were always other nights.

Then a carriage came rattling toward him. He recognized it immediately, for he had ridden in it many times. Desperately, he lunged forward. “Sir Toby!” The words flew from his mouth like ravens. He was running alongside the carriage now, waving, frantically trying to attract the man’s attention. Above him, he could see the coachman lifting his whip to warn him off.

But now, in the carriage window, that round, complacent face turned and its eyes widened in astonishment. “Ritter!” Sir Toby flung open the door and, extending a hand, pulled Ritter into the interior, alongside him. They tumbled down together in a heap and then clumsily righted themselves.

He was inside, and the carriage hadn’t even slowed down.

“I . . . have . . . a . . . message,” he gasped. It seemed he would never catch his breath. “For . . . you.”

“My dear fellow, I thought you were—well, never mind what I thought. It is wonderful to see you again. We must get you into some clean clothes. A good meal wouldn’t hurt either, by the look of you. I’ll rent you a room at the Club; it isn’t normally allowed, but I think I can swing it. Oh, dear me, you do look dreadful. What Hells you must have been through.”

“The . . . message.” Ritter reached inside his greatcoat, fumbling for an inner pocket.

“There will be plenty of time for that after you eat.” Sir Toby patted his arm soothingly.

“No . . . it . . .” To his astonishment Ritter saw his hand emerge clutching the Sheffield knife he had been given so long ago.

And then he was stabbing and stabbing and stabbing and blood spurted everywhere.

“There’s our first drop of water,” Dr. Nergüi said.

“Don’t try to be a man of iron.” Borsuk produced a handkerchief and Ritter buried his face in it. “It’s all right to cry.”

To his horror, Ritter felt great wracking sobs of grief welling up within him. It took all of his strength to hold them back. He was not sure he could do so indefinitely. But a cold, distant part of his mind thought: All right, then, and reached out into the darkness.

If this was how they were going to play the game, he would match them parry for thrust. He imagined Freki as he would be were he human: Hulking, rangy, shaggy, dangerous. A murderer if need be, but utterly without malice and unswervingly loyal to his friends. Wolfish, in a word. Layer by layer, he created this fiction, until all it lacked was a name fitting for a man. Ritter chose Vlad. Vlad, he thought. Come. The wolf would not understand why the image of a human he did not know was being pressed into his mind. But he was trained to obey a command. He emerged from the culvert in which he had been hiding.

Simultaneously, Ritter let the tears out. He had, he discovered with great surprise, rather a lot to cry about. Losses he had never mourned. Sorrows he had suffered and then locked away within himself. Well, then, he would make them work for him.

Ritter threw his head back and howled.

“I think he is ready,” Borsuk said at last.

“Excellent work. I’ll hold him passive. You start the questioning.”

Almost, Ritter slept. But though he fell into a restful lassitude, his eyes did not close. He simply felt unable, or perhaps unwilling, to act. It was like that state of borderline sleep when one is fully aware of one’s surroundings and struggles to awaken yet cannot. In a distant part of his brain, he could feel Freki trotting silently across the fields toward the sanitarium. But of course his captors weren’t looking there. Just into his surface thoughts. Borsuk reached over to brush back into place a strand of hair that had fallen over Ritter’s forehead. “Tell us a secret, my dear. Nothing big, nothing important. Just a little one to start with.”

Ritter shook his head. Or maybe he only meant to.

“You know you must. You’ve seen that you will. Why put off the inevitable?”

“There is—” Ritter stopped.

“Yes?”

With all the reluctance he could put into his voice, Ritter said, “A map. Sewn into the lining of my greatcoat.”

“Is there really?” Borsuk sounded pleased. He stood and went into the bedroom. When he returned, he had Ritter’s knife, which he used to cut open the coat. From the lining he extracted a square of white silk on which was printed a detailed map of the region. Ritter’s meeting place with his contact was not marked on it. But of course they already knew that.

Borsuk let the map flutter down onto a stand next to the couch and laid the knife atop it. Ritter tried not to show how aware he was of the knife’s proximity. But a wry chuckle from Dr. Nergüi told him that that the blade had again been rendered untouchable by him.

“You see? The world is unchanged. Save for how much better you feel now that you’re no longer struggling in a lost cause. Now. Tell me the name of your companion, the one we haven’t caught yet.”

Ritter heard himself say, “Vlad.”

“Your friend is a Slav, then?”

“It is a nickname,” Ritter said in a dead voice.

“Ahhh. After the Impaler, no doubt. Tell us about him.”

Slowly at first, and then volubly, Ritter began describing the Freki-analogue as he had re-imagined him: Vlad’s strength, both mental and physical. His dedication to his partner’s welfare. The playful side that came out at unexpected moments. His gluttonous appreciation of food. All the while feeling Freki coming closer and closer, until finally he stopped, just outside the sanitarium. Ritter felt a gentle yet unmistakable mental nudge. Freki was awaiting further orders.

“Enough.” Dr. Nergüi held up a hand. “Where is he now?”

Ritter managed to crack the slightest of smiles. He turned his head toward the window and sensed that the others did too. “Look there.”

Shards of glass and wood exploded inward as Freki came crashing into the room.

In that instant of shock, the two alienists lost all control over their conscious thoughts, and thus over Ritter. Freed of them, he came up from the couch, slapping a hand on the side table to seize the knife. This time, his fingers easily closed about its handle.

He buried it in Borsuk’s heart.

Freki had Dr. Nergüi down on the floor, with his teeth in her throat. Ritter was bit twice in the course of pulling the wolf away from the old woman’s corpse. But it was imperative to separate the two of them as quickly as possible. He didn’t want Freki to acquire a taste for human flesh.

The address Ritter had been given was a piece of wasteland, neither field nor commons, close by an old town dump. It was terrifyingly exposed space. He supposed that his contact wanted to be sure, on his approach, that only one man was waiting for him. Still, it was dreadfully open. He built himself a small vagrant’s camp there and waited, in constant danger of being discovered by foraging soldiers or a press gang.

He did not know who he was waiting for—Ritter only had a code name, a nom de guerre, for his contact. He had arrived at dawn on the day appointed, to find only empty land. Nor had the man he expected shown up by sundown. In such an event, he had been told, he was to wait three days. No more, no less. He had already waited two.

Ritter was bent over his wee fire, nursing along a pot of watery rabbit stew, when Freki whined from beneath the grey blanket that hid his presence from prying eyes, warning him that somebody was approaching.

Slowly, Ritter stood.

The man who came walking across the barren land was at least a decade older than himself. By his clothing, a man of substance. By his wariness, no friend of the Mongolian Wizard or his empire. He carried a walking stick which Ritter suspected was more than it seemed. Though Ritter knew himself to be a fearsome sight after all he had been through, the stranger continued steadily toward him.

When he reached the campfire, the man stopped. He looked evenly at Ritter, with neither trust nor fear. He said nothing. He appeared to be equally prepared to fight or to bolt. Ritter knew this could only be the man he had been waiting for.

Extending his hand, Ritter said, “The wizard Godot, I presume?”

“House of Dreams” copyright © 2013 by Michael Swanwick

Art copyright © 2013 by Gregory Manchess