Is The Nightmare Before Christmas a Halloween movie, or a Christmas movie? In terms of worldbuilding, it’s obviously both—it’s about a bunch of Halloween-town residents taking over Christmas from Santa Claus.

But worldbuilding elements don’t suffice as genre classifiers, or else black comedies wouldn’t exist. Creators deliberately apply worldbuilding elements from one genre to another for pure frission’s sake. Consider Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (speaking of Christmas movies), which takes a New York noir character, a down-on-his-luck con, and drops him into an LA noir scenario of movie glitz and private eyes; or Rian Johnson’s amazing Brick, a noir story engine driving high school characters. Fantasy literature is rife with this sort of behavior—consider Steven Brust’s use of crime drama story in the Vlad Taltos books, or for that matter the tug of war between detective fiction and fantasy that propels considerable swaths of urban fantasy. If we classify stories solely by the worldbuilding elements they contain, we’re engaging in the same fallacy as the Certain Kind of Book Review that blithely dismisses all science fiction as “those books with rockets.”

And what happens after the slippery slope? The No True Scotsman Argument?!

This is a frivolous question, sure, like some of the best. But even frivolous questions have a serious edge: holidays are ritual times, and stories are our oldest rituals. The stories we tell around a holiday name that holiday: I’ve failed at every Christmas on which I don’t watch the Charlie Brown Christmas Special. When December rolls around, even unchurched folk can get their teeth out for a Lessons & Carols service.

So let’s abandon trappings and turn to deep structures of story. Does The Nightmare Before Christmas work as Christmas movies do? Does it work as Halloween movies do? It can achieve both ends, clearly—much as a comedy can be romantic, or a thriller funny. But to resolve our dilemma we must first identify these deep structures.

What Defines a Halloween Movie?

Halloween movies are difficult to classify, because two types of movie demand inclusion: movies specifically featuring the holiday, like Hocus Pocus or even E.T., and horror movies, like Cabin in the Woods, The Craft, or The Devil’s Advocate. Yet some horror movies feel definitely wrong for Halloween—Alien, for example. Where do we draw the line?

I suggest that movies centering on Halloween tend to be stories about the experimentation with, and confirmation of, identities. Consider, for example, It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown, which might at first glance be mistaken for a simple slice of life featuring the Peanuts characters’ adventures on Halloween. In fact, the story hinges on the extent to which the various Peanuts’ identities shine through the roles they assume. Charlie Brown is the Charlie Browniest ghost in history; a dust cloud surrounds Pig Pen’s spirit. Snoopy operates, as always, in a liminal space between fantasy and reality—he becomes the most Snoopy-like of WWI fighter aces. Linus, whose idealism and hope are the salvation centerpiece of A Charlie Brown Christmas, isn’t equipped for the kind of identity play the other characters attempt. He’s too sincere for masks, and as a result becomes the engine of conflict in the story. For Linus, every holiday must be a grand statement of ideals and hope. In a way, Linus is rewarded—he meets the Avatar of Halloween in Snoopy’s form, but fails to appreciate the message sent, which is that Halloween is an opportunity for play, for self-abandonment. It’s Lucy who turns out to be the truest embodiment of the holiday—by explicitly donning her witch mask, she’s able to remove it, and bring her brother home.

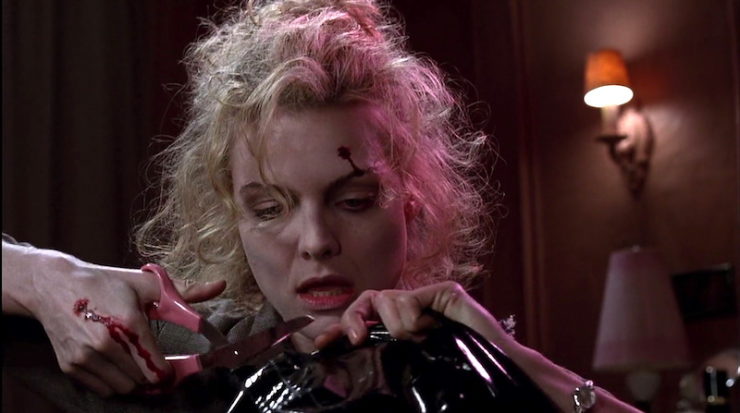

Even movies that feature Halloween in passing use it to highlight or subvert their characters’ identities by exploiting the double nature of the Halloween costume: it conceals the wearer’s identity and reveals her character at once. In E.T.’s brief Halloween sequence, for example, while Elliott’s costume is bare-bones, Michael, Mary, and E.T. himself all shine through their costume selections, literally in the case of E.T. The Karate Kid’s Halloween sequence highlights Danny’s introversion (he’s literally surrounded by a shower curtain!) and the Cobra Kai’s inhumanity (skeletons with all their faces painted identically!). Even holiday movies like Hocus Pocus that aren’t principally concerned with costuming present Halloween as a special night for which identities grow flexible: the dead can be living, the living dead, and a cat can be a three-hundred-year-old man.

If we expand our focus to include books that focus or foreground Halloween, we find Zelazny’s A Night in the Lonesome October, Raskin’s The Westing Game, and Bradbury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes, all of which focus on the experimentation with, or explicit concealment of, identities, and the power of revelation. Fan artists get in on the fun too—every time Halloween rolls around, I look forward to sequences like this, of characters from one medium dressed up as characters from another.

The centrality of identity play to the holiday explains why some horror movies feel “Halloween-y” while others don’t. Alien, for example, is a terrifying movie, one of my favorites, but with one notable exception it doesn’t care about masquerades. Cabin in the Woods, on the other hand, feels very Halloween, though it’s less scary than Alien—due, I think, to its focus on central characters’ performance of, or deviation from, the identities they’ve been assigned.

Examined in this light, The Nightmare Before Christmas is absolutely a Halloween movie. The entire film’s concerned with the construction and interrogation of identity, from the opening number in which each citizen of Halloween Town assumes center stage and assumes an identity (“I am the shadow on the moon at night!”), to Jack’s final reclamation of himself—“I am the Pumpkin King!”

So, are we done?

Not hardly.

The Common Core of Christmas Stories

Christmas films are easier, because there’s basically one Christmas story, shot over and over again down the decades: the tale of a community healing itself.

A Charlie Brown Christmas features all the Peanuts characters at their dysfunctional and at times misanthropic best, but it lands as a Christmas story through Linus’ speech, which fuses the shattered community and allows their final chorus. Home Alone’s break-ins and booby traps knit into a Christmas story by their depiction of Kate’s trip to join her son, and Kevin’s realization that he actually misses his family. The perennial Christmas fable Die Hard likewise starts with a broken family and moves toward reunification, with incidental terrorism and bank robbery thrown in to keep things moving.

The most famous Christmas story of all, A Christmas Carol, does focus on a single character—but Dickens depicts Scrooge as a tragic exile ultimately saved by his decision to embrace his community, in spite of the tragedies inflicted upon him. It’s a Wonderful Life tells the Christmas Carol story inside out: George Bailey doubts whether his life has meaning, given his lack of success by external, materialistic standards—but in the end his community reaffirms his value.

(By this reading, the Christmas story becomes the polar opposite of the standard Western / action movie formula of the Lone Rugged Individualist who Saves the Day. Which leads, in turn, to an analysis of Die Hard and the films of Shane Black beyond the scope of this article. For future research!)

So, if Christmas movies are movies about the healing of a fractured community, does The Nightmare Before Christmas fit the bill?

It seems to. Jack’s decision to walk away from the community of Halloween Town is the story’s inciting incident, and the film ends with the Town heralding his return, and his own offer of a more personal sort of community to Sally. (Speaking of which, I defy you to find an on-screen romance sold more effectively through fewer lines of dialogue. It’s one of moviemaking’s minor miracles that “My dearest friend / if you don’t mind” succeeds even though Jack and Sally exchange perhaps a hundred words over the course of the whole film.) So, we have a Christmas story!

…But What Does It Mean?

A Nightmare Before Christmas seems to satisfy both classifiers, being both a story about an exile finding his way back to his community, and a story about identity play. We can safely watch it for each holiday without confusing our rituals!

But I think the film actually goes a step beyond merely satisfying as both a Christmas movie and a Halloween movie—the two story structures inform one another. We start firmly in Halloween, with a song of identity declaration. “I am the Clown with the Tear-away Face,” the movie’s opening number proclaims, and we meet Jack as the Pumpkin King. But the identities assumed here are too narrow to satisfy. Jack has mastered Pumpkin King-ing, but mastery has trapped him inside that identity. He feels sickened by his station, like a child who’s eaten too much candy.

And no surprise! For Jack, and to a lesser extent for the rest of the Town, the play has faded from Halloween. It’s a job, complete with after-action conferences, meaningless awards, and group applause; not for nothing is the Mayor’s character design functionally identical to that of Dilbert’s Pointy Haired Boss. Jack’s malaise parallels the crisis of the college graduate or midlife office worker, who, having spent a heady youth experimenting with different identities, finds herself stuck performing the same damn one every day.

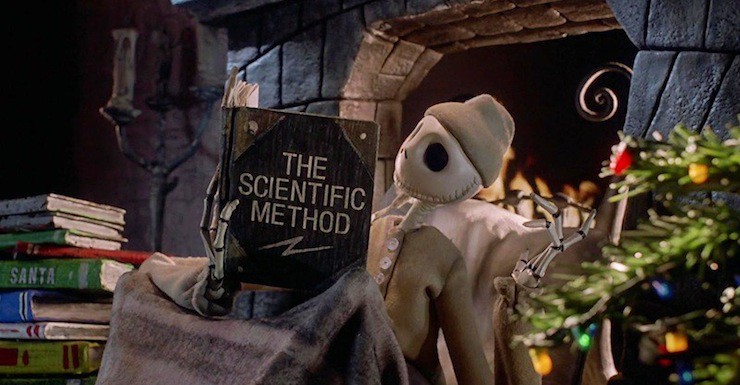

Jack’s discovery of Christmas forces him into a new relationship with his community. Setting aside his unquestioned rule of Halloween Town, he becomes its Christmas evangelist; he cajoles, convinces, and inspires Halloween Town’s people to pursue a vision they never quite grasp. His Christmas quest unites, transforms, and expands his people, while at the same time revealing them—the Doctor develops flying reindeer, the band plays new tunes, the vampires learn to ice skate. The Christmas experiment allows Halloween Town to experience the transgressive joy of the holiday the town is supposed to promote: that of donning masks, applying paint, assuming a different form—and yet remaining yourself. The entire community plays Halloween together, wearing the mask of Christmas. In attempting to lose themselves, they find themselves again.

In the end, Halloween Town’s Christmas experiment terrifies the mortal realm far more than their Halloween itself. By encouraging his community to play, and by playing himself, Jack expands his identity, and theirs—and with his new, more roomy self, he finally sees Sally as a person and a companion, as “my dearest friend” rather than just another citizen.

The holidays for which cards and candy are made serve America for rituals. They chart our life’s progress. Halloween’s the first folk duty we ask young children to perform under their own power, the first time we ask them to choose faces. Costume choice is practice for the day we ask “what do you want to be when you grow up?” On Thanksgiving we remember how contingent and accidental are those faces we’ve assumed—and we recognize (or should) how many skeletons lie buried under our feet. That’s the awakening of political consciousness, the knowledge that we have received, and taken, much. Then comes Christmas, in which the year dies, and we must love one another or die too.

And then, after a long winter broken only by a few candy hearts, we reach Easter.

The Nightmare Before Christmas endures, I think, because it’s about the operation, not the celebration, of holidays. It’s a movie about the function and value and power of Halloween and Christmas both; there are even notes of Easter in the kidnapped bunny, and Jack’s momentary Pietà. The film invites us to stretch our holidays beyond their limits, to let Halloween and Christmas chat and eye one another warily.

Plus, the music’s great.

This article was originally published in December 2014.