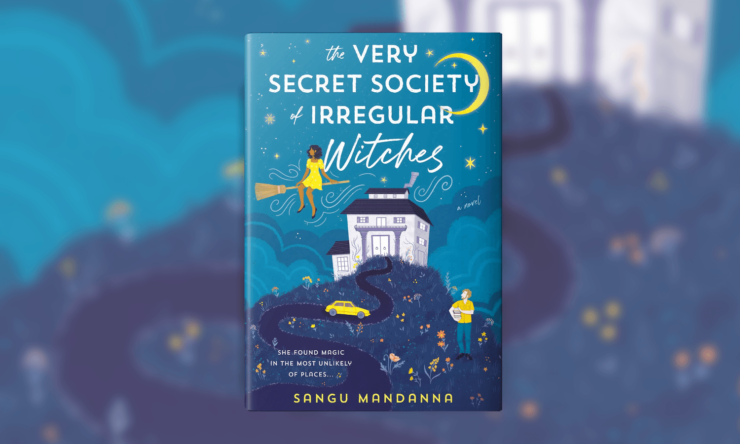

Mika Moon, the protagonist of Sangu Mandanna’s The Very Secret Society of Irregular Witches, was orphaned at a young age (as all witches are) and has grown up with the certainty that she will always be alone. Witches mustn’t congregate, lest they create a magical surge that attracts the attention of normal people, which “witches have discovered time and time again over the centuries is dangerous.” For the most part, Mika plays by the rules. Her one rebellion is the YouTube channel where she posts videos of real magic that she pretends is fake magic, but that’s exactly what gets her into trouble when she’s contacted to teach magic to a household of three (!!) very young witches. Their home, Nowhere House, belongs to a witch named Lillian who spends most of her time overseas and leaves the day-to-day operations of Nowhere House and its orphan witches to her staff: housekeeper Lucie, groundskeeper Ken and his actor husband Ian, and Jamie, the hot, grumpy librarian. Mika knows she can’t belong with them forever, but oh, how she wants to.

If you keep an eye—and for your sake I hope you don’t—on fearmongering leftist thinkpieces of the type that Michael Hobbes thrives on debunking, you’ve probably seen at least one op-ed about how kids (read: adults) these days just cut their family members out of their lives at the drop of a hat and without a backward glance. For minor offenses! What next! It’s a slippery slope! And it’s the internet’s fault, probably!

Emily St. James notes that the idealization of nuclear and biological family is too often predicated on obligation, or lack of choice. Common wisdom holds that you can be as mean to your sister as you want because she’s stuck with you. When you have no choice but to go to your family for help, they have no choice but to take you in. I find it horribly grim, this vision of family relationship as hostage crisis. When I was being trained as a suicide intervention counselor, we were taught not to say have to at all because it erases choice and agency. We do not have to invite the lech uncle to every holiday. We do not have to keep the damaging family secrets. We choose not to talk about Bruno.

Although nobody asked, I will take this opportunity to share my opinion that While You Were Sleeping is the best rom-com ever made, and the reason this is true is that Lucy falls in love—she says so!—not just with Bill Pullman, whose furniture business I don’t think is sustainable anyway, but with his big, loud, weird Catholic family. (This resonates with me because I myself come from a big, loud, weird Catholic family that everyone, correctly, falls in love with.) There’s a moment at the family Christmas celebration, to which Lucy has been invited after saving the family’s eldest son from death by train, when someone puts a Christmas present in Lucy’s hands. We never find out what the gift is, because Lucy never unwraps it; she just sits there holding it, letting the family’s boisterous chatter wash over her, delight and wonder written all over her face.

The defining features of a romance novel are these: the story is centrally focused on the progression of a romance, and the characters who are having the romance end up happily partnered. While these requirements too often lead the genre to imply (or state outright) that the only type of love that matters is romantic love accompanied by sexual attraction, the genre at its best also celebrates the bonds of family and community, and the ability of its characters to find happiness and fulfillment within those contexts too.

Mika has grown up under the devastating weight of family secrecy and control. Primrose, the witch who raised her after her parents died, surrendered the bulk of her care to a series of nannies, all of whom were summarily dismissed and magically memory-wiped by Primrose when they had caught wind of what Mika could do. “They always knew I was different,” she confesses to Jamie, early in her stay at Nowhere House. “It took me years to work out how to behave like I was expected to.” It doesn’t occur to her—yet—that there was or could be an alternative to this rigidly enforced control, a version of her life in which she’s loved for who she is.

She answers the summons to Nowhere House because of the desperation she can sense in the message from Ian. She’s prepared to be useful, but not to be wanted. Her version of Lucy tenderly cradling a Christmas gift comes when Mika asks the children’s guardians to weigh in on the safety of taking the oldest girl, Rosetta, into town to visit a bookshop. Ken is mildly opposed, while Lucie and Ian are in favor, and our hot librarian Jamie is inclined to say absolutely not. Ian points out that if Mika had raised the question after her two-week trial period had concluded, she’d have been able to break the tie with a vote of her own—a point that Mika has obviously never considered.

Mika continued to look stunned, like it had never occurred to her that she might be considered part of something, and Jamie found he violently hated it. He was livid that she was so surprised by such a simple gesture. Hadn’t she ever been treated as anything but an outsider?

The answer is no, she hasn’t. As we learn later in the book, the best she’s ever been able to expect from those closest to her has been the desire to use her powers for their own benefit. She reluctantly discloses the existence of a single serious ex-boyfriend, who learned that she was a witch and then began making demands. Cash bewitched out of an ATM machine. Answers magically provided to him during exams. Nor, she admits, was it the first time. When the nannies of her childhood learned what she could do, “I became something that could be used.”

As she gradually comes to learn from the denizens of Nowhere House, this isn’t the most a person can hope for—even a witch. Jamie, Ian, Lucie, and Ken, to say nothing of the girls, care about Mika. They include her and make space for her. She comes to Nowhere House with her own greenhouse, and she gardens with Ken. Jamie brings whiskey upstairs to her and helps with her spellwork. When she’s ill from a magical backlash, they take it in turns to sit by her bedside in case she wakes up and needs anything. It’s Mika’s first real experience of the quotidian miracle of being loved.

Buy the Book

The Very Secret Society of Irregular Witches

Particularly when a character comes to a chosen family from a deeply dysfunctional family of origin, there’s an inclination to idealize the new. Much as romance novel heroes are prone to knowing exactly what sorts of sex things their partner will enjoy without having to ask or making mistakes or sitting on the other person’s hair (shouts to Ruthie Knox, Courtney Milan, and Cecelia Grant for schooling me on the value of bad sex scenes in romance novels), fictional found families are prone to getting everything right on the first try. It’s a trap Mandanna doesn’t fall into, and indeed the third-act conflict of Irregular Witches arises between Mika and the whole family, rather than exclusively between herself and her love interest.

And it’s a serious one: She learns that Jamie, and Ian and Ken, and Lucie, have been lying to her all along. The girls’ witch guardian, Lillian, hasn’t gone unreachable on a long research trip to remote locations without cell services. She has died, and the four adults of Nowhere House are trying to keep that fact from her solicitor to ensure that they’ll retain custody of the girls, who have never known another home. It’s a shattering realization to Mika, as she looks back on every interaction she’s shared with them and sees ulterior motives where she had barely begun to allow herself to see trust. Heartbroken, she tells Jamie, “I can never know how much of it was real.”

There’s a remarkable power in realizing that you can choose the people with whom you share reciprocal relationships of care. When Mika makes the leap of faith to give Jamie and the others a second chance, she’s acting from a place of trust in the life she has built with them, rather than a place of fear that their failure of care for her will be repeated. We even see her begin to build a new relationship with Primrose, the witch who raised her, a choice she’s only able to make because her time at Nowhere House has taught her that she can be vulnerable enough to ask for what she needs, and strong enough to walk away from relationships with people who won’t meet her halfway.

The allure of found family is precisely that we are choose and are chosen by them. Mika does not have to go back to Jamie, Ken, Ian, and Lucie, any more than they have to take her back. They are not family by an accident of biology, or out of obligation to the dictates of a societal narrative. They’ll share interests and set boundaries and help one another when help is needed. To paraphrase the wonderful Gwendolyn Brooks, they are each other’s business, bound together by the choice to give and receive love.

Jenny Hamilton reads the end before she reads the middle. She reviews for Strange Horizons and Lady Business and can be found at her website or on Twitter @readingtheend.