Between 1974 and 1980, John Varley wrote thirteen stories and one novel in the classic Eight Worlds setting. These worlds do not include Earth, which has been seized by aliens. Humans on the Moon and Mars survived and prospered. Humans have spread across the Solar System (with the exception of alien-owned Jupiter and Earth). The human past has been marked by a calamitous discontinuity (the Invasion and the struggle to survive the aftermath), but their present is, for the most part, technologically sophisticated, peaceful, stable, and prosperous.

Peace and prosperity sound like they’re good things, but perhaps not for authors. What kind of plots can be imagined if the standard plot drivers are off the table? How does one tell stories in a setting that, while not a utopia, can see utopia at a distance ? The premise seems unpromising, but thirteen stories and a novel argue that one can write absorbing narratives in just such a setting. So how did Varley square this particular circle?

The thirteen stories are:

- “Beatnik Bayou”

- “The Black Hole Passes”

- “Equinoctial”

- “The Funhouse Effect”

- “Good-bye Robinson Crusoe”

- “Gotta Sing, Gotta Dance”

- “In the Bowl”

- “Lollipop and the Tar Baby”

- “Options”

- “Overdrawn at the Memory Bank”

- “The Phantom of Kansas”

- “Picnic on Nearside”

- “Retrograde Summer”

The lone novel was The Ophiuchi Hotline.

Let’s start with the outlier:

“The Black Hole Passes” is a human-versus-nature tale. Given that humans are forced to live on worlds that would kill them deader than doornails if their machines break down, you might expect that such perils would be common plot points. They are uncommon, however, because Eight Worlds’ technology is very, very good. The null-suit in particular is an all-purpose protection. A null-suited Eight Worlder can wander on the surface of Venus as if it were Algonquin Park . This story explores the uncommon case of an event that could kill an Eight Worlder (and worse, play havoc with his love life).

“Options” is also an outlier in that it’s set in a time when the ability to switch between male and female bodies cheaply and conveniently has become the New Thing. Rather than exploring a world where such procedures are a commonplace choice (Varley does that in the other Eight World stories), it explores what happens immediately after the introduction of a socially disruptive technology.

One might think of The Ophiuchi Hotline and “The Phantom of Kansas” as crime fiction. In the first, the protagonist is snatched from the brink of execution because a criminal mastermind (who believes they are the saviour of mankind) wants to recruit her for their organization. In the second, an artist wakes to discover he has been murdered, not once but several times. Cloning + memory records permit serial incarnations, but all the same, our hero would prefer not to be murdered again. He needs to find out who’s doing the killing and why.

Both “Beatnik Bayou” and “Lollipop and the Tar Baby” address the theme of inter-generational conflict. In “Beatnik,” a teacher-student relationship goes sour; in “Lollipop” a child gradually realizes that their parent does not have their best interests at heart. One could make a case that Lollipop belongs in the crime category (or that I should learn how to use Venn diagrams), except I am not sure the scheme is illegal. It might be marginally legal.

Artistic differences drive the plots of “Equinoctial” and “Gotta Sing, Gotta Dance.” Aesthetic disputes may seem harmless enough…but consider the Paris reception of Le Sacre du printemps. Removing issues like hunger or housing doesn’t make passion vanish. It just changes the focus of passion.

What drives a surprisingly high fraction (almost half) of the classic Eight Worlds stories? Holidays. Wealth and leisure mean having time to fill. If there is anything that the Eight Worlders love more than tourism, it’s getting into wacky complications thanks to their travels. “The Funhouse Effect,” “Goodbye, Robinson Crusoe,” “In the Bowl,” “Overdrawn at the Memory Bank,” “Picnic on Nearside,” and “Retrograde Summer” all involve tourism.

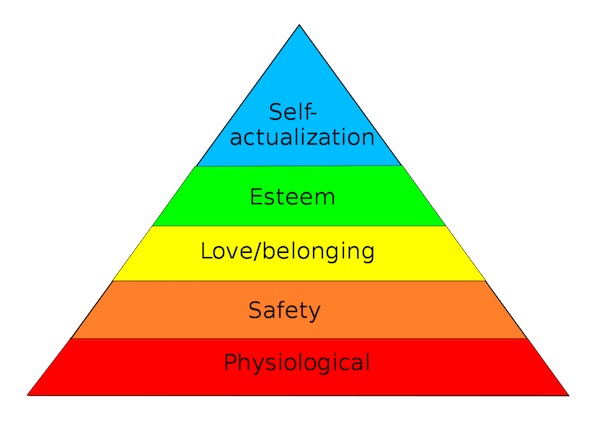

SF authors seem to prefer plots in which survival and safety are at stake. Those are the first two needs in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (physiological, safety, love/belonging, esteem, and self-actualization).

Those needs are the base of the pyramid. If you don’t satisfy those, you cannot meet any of the higher needs. If your plot hinges on those basic needs, you’ve got high stakes and possibly a gripping narrative.

Varley, though, has imagined a world in which survival and safety are rarely at stake. His characters need love, esteem, and self-actualization, and suffer if those are lacking. He is a good enough writer to have turned those needs into absorbing narratives. This isn’t a common choice: consider, for example, Banks’ Culture novels. Although the Culture is a utopia, Banks hardly ever set his stories there. Instead, he preferred stories set outside the Culture, stories that often involve Special Circumstances. It is easy to write about citizens of utopias if they head outside the utopia to have fun. Varley’s choice is a bold one but the resulting classic Eight World stories stand as examples of how a writer can overcome the handicap of having set their stories in a nightmarish future of peace and prosperity.

Not many authors have duplicated Varley’s feat in the classic Eight Worlds stories. But a few have. Who? Well, that’s another essay.

1: Why aren’t the Eight Worlds a utopia? In my opinion, widespread illiteracy is a minus. Also, adults perving on tweens is both frequent and accepted, something I would like to encounter in SF a lot less frequently than I actually do.

2: Even close approaches to the Sun are survivable. Null-suits are reflective. They do diddly-squat about gravity, however, so try not to fall into any black holes.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is surprisingly flammable.