Sometimes, the right book comes along with the right message at the right time and ends up not only a literary classic, but a cultural phenomenon that ushers in a new age. One such book is the first official, authorized paperback edition of The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien…

And when I talk about the book ushering in a new age, I’m not referring to the end of the Third and beginning of the Fourth Age of Middle-earth—I’m talking about the creation of a new mass market fictional genre. While often comingled with science fiction on the shelves, fantasy has become a genre unto itself. If you didn’t live through the shift, it’s hard to grasp how profound it was. Moreover, because of the wide appeal of fantasy books, the barriers around the previously insular world of science fiction and fantasy fandom began to crumble, as what was once the purview of “geeks and nerds” became mainstream entertainment. This column will look at how the book’s publishers, the author, the publishing industry, the culture, and the message all came together in a unique way that had a huge and lasting impact.

My brothers, father, and I were at a science fiction convention—sometime in the 1980s, I think it was. We all shared a single room to save money, and unfortunately, my father snored like a freight train chugging into a station. My youngest brother woke up early, and snuck out to the lobby to find some peace and quiet. When the rest of us got up for breakfast, I found him in the lobby talking to an older gentleman. He told me the man had bought breakfast for him and some other fans. The man put his hand out to shake mine, and introduced himself. “Ian Ballantine,” he said. I stammered something in reply, and he gave me a knowing look and a smile. He was used to meeting people who held him in awe. I think he found my brother’s company at breakfast refreshing because my brother did not know who he was. Ballantine excused himself, as he had a busy day ahead, and I asked my brother if he knew who he had just shared a meal with. He replied, “I think he had something to do with publishing The Lord of the Rings, because he was pleased when I told him it was my favorite book.” And I proceeded to tell my brother the story of the publishing of the paperback edition of The Lord of the Rings, and its impact.

About the Publishers

Ian Ballantine (1916-1995) and Betty Ballantine (born 1919) were among the publishers who founded Bantam Books in 1945, and then left that organization to found Ballantine Books in 1952, initially working from their apartment. Ballantine Books, a general publisher that devoted special attention to paperback science fiction books, played a large role in the post-World War II growth of the field of SF. In addition to reprints, they began publishing paperback originals, many edited by Frederik Pohl, which soon became staples of the genre. Authors published by Ballantine included Ray Bradbury, Arthur C. Clarke, C. M. Kornbluth, Frederik Pohl, and Theodore Sturgeon. Evocative artwork by Richard Powers gave many of their books’ covers a distinctive house style. In 1965, they had a huge success with the authorized paperback publication of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. Because the success of that trilogy created a new market for fantasy novels, they started the Ballantine Adult Fantasy line, edited by Lin Carter. The Ballantines left the company in 1974, shortly after it was acquired by Random House, and became freelance publishers. Because so much of their work was done as a team, the Ballantines were often recognized as a couple, including their joint 2008 induction into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame.

About the Author

J.R.R. Tolkien (1892-1973) was a professor at Oxford University who specialized in studying the roots of the English language. In his work he was exposed to ancient tales and legends, and was inspired to write fantasy stories whose themes harkened back to those ancient days. His crowning achievement was the creation of a fictional world set in an era that predated our current historical records, a world of magical powers with its own unique races and languages. The fictional stories set in that world include The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, as well as a posthumously published volume, The Silmarillion. Tolkien also produced extensive amounts of related material and notes on the history and languages of his fictional creation. He was a member of an informal club called the Inklings, which also included author C. S. Lewis, another major figure in the field of fantasy. While valuing the virtues and forms of bygone eras, his works were also indelibly marked by his military experience in World War I, and Tolkien did not shy away from portraying the darkness and destruction that war brings. He valued nature, simple decency, perseverance and honor, and disliked industrialism and other negative effects of modernization in general. His work also reflected the values of his Catholic faith. He was not always happy with his literary success, and was somewhat discomforted when his work was enthusiastically adopted by the counterculture of the 1960s.

The Age of Mass Market Paperback Books Begins

Less expensive books with paper or cardboard covers are not a new development. “Dime” novels were common in the late 19th Century, but soon gave way in popularity to magazines and other periodicals which were often printed on cheaper “pulp” paper. These were a common source of and outlet for genre fiction. In the 1930s, publishers began experimenting with “mass market” paperback editions of classic books and books that had previously published in hardcover. This format was widely used to provide books to U.S. troops during World War II. In the years after the war, the size of these books was standardized to fit into a back pocket, and thus gained the name “pocket books.” These books were often sold in the same way as periodicals, where the publishers, to ensure maximum exposure of their product, allowed vendors to return unsold books, or at least return stripped covers as proof they had been destroyed and not sold. In the decades that followed, paperback books became ubiquitous, and were found in a wide variety of locations, including newsstands, bus and train stations, drug stores, groceries, general stores, and department stores.

The rise of paperback books had a significant impact on the science fiction genre. In the days of the pulp magazines, the stories were of shorter length—primarily short stories, novelettes, and novellas. The paperback, however, lent itself to longer tales. There were early attempts to fill the books with collections of shorter works, or stitch together related short pieces into what was called the “fix-up” novel. Ace Books created what was called the “Ace Double,” two shorter works printed back to back, with each having its own separate cover. Science fiction authors began to write longer works to fit the larger volumes, and these works frequently had their original publication in paperback format. Paperbacks had the advantage of being less expensive to print, which made it possible to print books, like science fiction, that might have narrower appeal and were aimed at a particular audience. But it also made it easier for a book, if it became popular, to be affordable and widely circulated. This set the stage for the massive popularity of The Lord of the Rings.

A Cultural Phenomenon

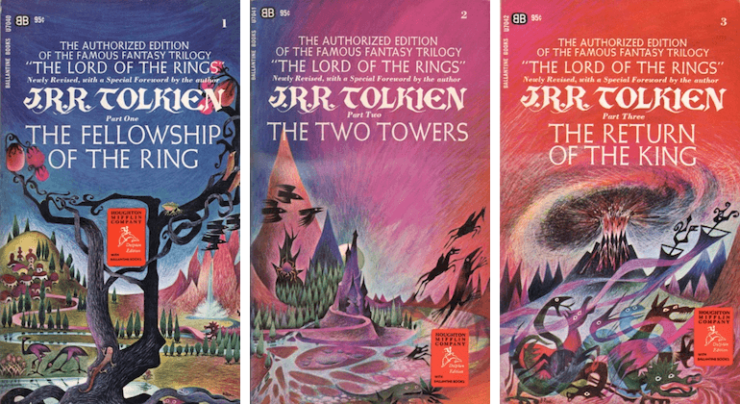

The Lord of the Rings was first published in three volumes in England in 1954 and 1955: The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, and The Return of the King. It was a modest success in England, and was published in a U.S. hardcover edition by Houghton Mifflin. Trying to capitalize on what they saw as a loophole in copyright law, Ace Books attempted to publish a 1965 paperback edition without paying royalties to the author. When fans were informed, this move blew up spectacularly, and Ace was forced to withdraw their edition. Later that year, the paperback “Authorized Edition” was released by Ballantine Books. Its sales grew, and within a year, it had reached the top of The New York Times Paperback Best Seller list. The paperback format allowed these books a wide distribution, and not only were the books widely read, they became a cultural phenomenon unto themselves. A poster based on the paperback cover of The Fellowship of the Ring became ubiquitous in college dorm rooms around the nation. For some reason, this quasi-medieval tale of an epic fantasy quest captured the imagination of the nation, particularly among young people.

It’s hard to establish a single reason why a book as unique and different as The Lord of the Rings, with its deliberately archaic tone, became so popular, but the 1960s were a time of great change and turmoil in the United States. The country was engaged in a long, divisive, and inconclusive war in Vietnam. In the midst of both peaceful protests and riots, the racial discrimination that had continued for a century after the Civil War became illegal upon passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Gender roles and women’s rights were being questioned by the movement that has been referred to as Second Wave Feminism. Because of upheaval in the Christian faith, many scholars consider the era to be the fourth Great Awakening in American history. Additionally, there was also wider exploration of other faiths and philosophies, and widespread questioning of spiritual doctrines. A loose movement that became known as “hippies” or the “counterculture” turned its back on traditional norms, and explored alternative lifestyles, communal living, and sex, drugs, and rock and roll. Each of these trends was significant, and together, their impact on American society was enormous.

The Lord of the Rings

At this point in my columns, I usually recap the book being reviewed, but I’m going to assume that everyone reading this article has either read the books or seen the movies (or both). So instead of the usual recap, I’m going to talk about the overall themes of the book, why I think it was so successful, and how it caught the imagination of so many people.

The Lord of the Rings is, at its heart, a paean to simpler times, when life was more pastoral. The Shire of the book’s opening is a bucolic paradise; and when it is despoiled by power-hungry aggressors it’s eventually restored by the returning heroes. The elves are portrayed as living in harmony with nature within their forest abodes, and even the dwarves are in harmony with their mountains and caves. In the decades after the book was published, this vision appealed to those who wanted to return to the land, and who were troubled by the drawbacks and complications associated with modern progress and technology. It harkened back to legends and tales of magic and mystery, which stood in stark contrast with the modern world.

The book, while it portrays a war, is deeply anti-war, which appealed to the people of a nation growing sick of our continued intervention in Vietnam, which showed no sign of ending, nor any meaningful progress. The true heroes of this war were not the dashing knights—they were ordinary hobbits, pressed into service by duty and the desire to do the right thing, slogging doggedly through a despoiled landscape. This exalting of the common man was deeply appealing to American sensibilities.

The book, without being explicitly religious, was deeply infused with a sense of morality. Compared to a real world filled with moral grey areas and ethical compromises, it gave the readers a chance to feel certain about the rightness of a cause. The characters did not succeed by compromising or bending their principles; they succeeded when they stayed true to their values and pursued an honorable course.

While the book has few female characters, those few were more than you would find in many adventure books of the time, and they play major roles. Galadriel is one of the great leaders of Middle-earth, and the courageous shieldmaiden Éowyn plays a significant role on the battlefield precisely because she is not a man.

And finally, the book gives readers a chance to forget the troubles of the real world and immerse themselves completely in another reality, experiencing a world of adventure on a grand scale. The sheer size of the book transports the reader to another, fully-realized world and keeps them there over the course of huge battles and long journeys until the quest is finally finished—something a shorter story could not have done. The word “epic” is overused today, but it truly fits Tolkien’s tale.

The Impact of The Lord of the Rings on the Science Fiction and Fantasy Genres

When I was first starting to buy books in the early 1960s, before the publication of The Lord of the Rings, there was not much science fiction on the racks, and fantasy books were rarely to be found. Mainstream fiction, romances, crime, mystery, and even Westerns were much more common.

After the publication of The Lord of the Rings, publishers combed their archives for works that might match the success of Tolkien’s work—anything they could find with swordplay or magic involved. One reprint series that became successful was the adventures of Conan the Barbarian, written by Robert E. Howard. And of course, contemporary authors created new works in the vein of Tolkien’s epic fantasy; one of these was a trilogy by Terry Brooks that began with The Sword of Shannara. And this was far from the only such book; the shelf space occupied by the fantasy genre began to grow. Instead of being read by a small community of established fans, The Lord of the Rings became one of those books that everyone was reading—or at least everyone knew someone else who was reading it. Fantasy fiction, especially epic fantasy, once an afterthought in publishing, became a new facet of popular culture. And, rather than suffering as the fantasy genre expanded its borders, the science fiction genre grew as well, as the success of the two genres seemed to reinforce each other.

One rather mixed aspect of the legacy of The Lord of the Rings is the practice of publishing fantasy narratives as trilogies and other multi-volume sets of books, resulting in books in a series where the story does not resolve at the end of each volume. There is a lean economy to older, shorter tales that many fans miss. With books being issued long before the end of the series is completed, fans often have to endure long waits to see the final, satisfying end of a narrative. But as long as it keeps readers coming back, I see no sign that this practice will be ending any time soon.

Final Thoughts

The huge success and broad appeal of The Lord of the Rings in its paperback edition ushered in a new era in the publishing industry, and put fantasy books on the shelves of stores across the nation. Within a few more decades, the fantasy genre had become an integral part of mainstream culture, no longer confined to a small niche of devoted fans. Readers today might have trouble imagining a time when you couldn’t even find epic fantasy in book form, but that was indeed the situation during my youth.

And now I’d like to hear from you. What are your thoughts on The Lord of the Rings, and its impact on the fantasy and science fiction genres?

Originally published in January 2019 as part of the Front Lines and Frontiers column.

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.

My original comment here still applies, so I’ll post it, because I also want to hear what others say :)

Thank you for this article! It seems that I am doomed to not get to experience some of my favorite things in real time. The first big ‘geeky’ loves of my life were the Beatles (maybe not really a ‘geeky’ thing, but my level of obsession with them was, especially growing up in the 80s/90s), Lord of the Rings and Star Wars, all things which pre-date me (born in 82, ha). But I guess I did get to ride the Harry Potter/Wheel of Time wave ;) And I feel like Weird Al is finally now getting the mainstream respect he deserves so I guess I have the right to be all hipster-y about that ;)

Regarding Lord of the Rings – honestly, it is probably what actually pulled me into hard core nerddom. When I was in sixth grade, one of my aunts passed away (quite tragically) and during the funeral I was a bit out of place, and one of my uncles was talking to me about the Lord of the Rings since he knew I loved to read. That Christmas he sent me the Hobbit and Fellowship.

I enjoyed them, although I know I missed a lot. I re-read them in 8th grade, taking my time, and was really blown away. At that time it was still kind of a weird thing to be into it – I had one friend who was also really into them and we used to try to answer insane trivia questions with each other. Somebody recommended the Silmarillion to me and it was a bit tricky to find. Of course, now, thanks to Peter Jackson, (whatever my complaints with the movies) we actually see people go on late night TV bragging about reading it, lol.

Speaking of subverting tropes, I think what is also notable is that, technically, his hero FAILS. At least, on his own power. He doesn’t return to the Shire triumphant and able to enjoy the fruits of his labor. He’s wounded and in need of healing for the rest of his days. Which, as mentioned, really is an anti-war story, and also one of great sacrifice. The story is about hope and perseverence, but always a thin strand of it, on the knife edge of despair. I really didn’t understand this until I was an adult.

@1, Weird Al is a cultural gem and no one can convince me otherwise.

@1 Weird Al was pretty well regarded in the early 80’s.

I had that poster showing all 3 book covers on my dorm room wall in the 1970’s. Anyone know if it is available anywhere?

Since writing this article, I have read further and found evidence that Ace was on pretty firm legal ground in publishing their paperback edition, and felt they were doing a service to fans who might find the hardback edition of the books too expensive. But regardless of their motives, and the legal merits of their position, once Tolkien had announced their edition was “unauthorized” on the back cover of the Ballantine edition, they had lost in the court of public opinion.

Betty Ballantine died last year – https://locusmag.com/2019/02/betty-ballantine-1919-2019/

A mere quibble, however – nice summary of the effect of TLotR at the time the paperbacks came out.

Today on January 3, One Hundred and Twenty Eight Years ago, J. R. R. Tolkien was born. He has been an author whose work has been near and dear to me for a very long time.

My acquaintance with J. R. R Tolkien began at when I was quite young back in 2000 or 2001. I was at the barber’s and happened to catch an ad for the upcoming release of Fellowship. Being an impressionable young child the concept of “Ringwraiths” caught my attention. When we returned home I took some aluminum foil and began to shape one. My father, noticed my work and asked me about it. Recognizing the term Ringwraith, he brought out his old paperback box set of the Lord of the Ring from his college days and gave it to me to read. I was immediately enamored by Tolkien’s prose. I read that set of books to death, pondering over the maps and appendixes. When the Jackson films first came out I went to see them with my Dad and my Godfather. I was blown away and would eagerly await each new installment.

In time I would acquire a copy of the Silmarillion and revel in the legends of the First Age that underlined Tolkien’s Middle Earth. Tolkien stands unique among writers in that his languages came first, then his mythology, with the Hobbit and Lord of the Rings being extension of his greater story. Since then my appreciation of Tolkien’s mythos has only grown.. I currently hold a considerable collection consisting of the twelve volume History of Middle Earth, multiple editions of the Lord of the Rings, Hobbit, and Silmarillion, in addition to numerous volumes on Tolkien’s life and work.

I will always be grateful to J. R. R. Tolkien for bringing his world of wonder and imagination to my life.

@5 It may have been “technically” legal according to the American copyright laws of the time, but it was ethically dubious and basically theft. The popularity of the Ace Edition ironically proved it’s downfall. Tolkien skillfully used his new fanbase to boycott the unauthorized Ace Edition and the sheer backlash forced Ace to pay him some of the lost royalties and to stop any new versions from being released. Tolkien basically created the Second Edition of LotR to secure the U.S copyright and offer an authorized edition for Ballantine.

Here’s a good article on the topic for anyone interested https://www.kirkusreviews.com/features/unauthorized-lord-rings/

This is entirely tangential to the topic and comments, but I never thought I would live to see a day when “hippies” was an unfamiliar term needing to be explained.

Had LOTR failed to capture the imagination of 60s counterculture, it likely would have slipped into obscurity and be long forgotten by now. The fact that Tolkien may owe his fame and influence to hippies is a delicious irony.

“There is a lean economy to older, shorter tales that many fans miss.”

And these days LotR itself is that older, leaner, tale. I think A Storm of Swords has about as many words as all of LotR, and that’s just one of a five-book (so far) series. Not to mention Jordan’s The Wheel of Overtime series.

The Silmarillion has a “heavy” reputation but it’s shorter than any of the LotR volumes. The main thing is that it’s mostly an anthology of myth and descriptive history, with disjoint bits of narration, so it’s very different from a dialogue-heavy story following Bilbo or some of the Fellowship characters around. (Despite the fact that elven immortality means that you *could* tell a story spanning hundreds or thousands of years from some one or few POVs…)

‘One book to rule them all.’ American fantasy authors have the same relationship with LOTR that Frodo has with the ring, imo. Personally, I always much preferred ‘The Hobbit.’

Beautiful cover art there. More intriguing than the stark simplicity of just rings on the cover.

One of the articles on TOR that I have most enjoyed in recent months. Many thanks.

Excellent article, one of better ones from Tor recently – thank you. Growing up I was more of a hard SF reader, devouring everything I could find by what I considered my “big three”: Heinlein, Clarke and Asimov. One of my mom’s coworkers introduced me to the Hobbit and that began to expand my horizons. I found copies of the Ballantine versions of LotR at Powell’s Used Book Store in Portland OR, and was immediately swept away by the breadth and depth of JRR Tolkien’s world-building. I started reading any other Ballantine fantasy I could get my hands on and even after nearly 50 years I still have my copies of the Worm Ouroboros, Titus Groan, Gormenghast as well as others. These Ballantine editions brought great comfort to a nerdy teen in the 60’s.

Ace was only on firm legal ground in the United States because the US version of copyright law has always prioritised American book-pirates over non-US authors or publishers. (Kipling wrote a vengeful poem about this situation – “The Rhyme of the Three Captains” though one now needs a crib to work out the names of the American publishers Kipling was insulting.) Outside the US, what Ace was doing was unlawful profiteering. I gather Tolkien’s letters were written more in sorrow than in anger, but they had an effect.

I love the Tolkien books. I do not love that an unintended consequence of their popularity–the killing off of standalone fantasy and to a lesser extent science fiction novels–was a result. These days someone like Clifford Simak or even Robert A. Heinlein would have a difficult time getting anything published.

Then there is the extension of that to “if three books are good then six must be better. Or why not 10 or 12?” At this point I’ve very nearly stopped reading genre fiction. The ultimate expression of that is the ridiculous situation with George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire which concluded its run on HBO years before the final book(s) were published.

Bigger is not always better although I’ll grant it sells more books.

So true, and also a special and major acknowledgement to Lin Carter who bought in a lot of old works to reprint with Ballantine Adult Fantasy series from writers such as Lord Dunsany’s ‘The King of Elfland’s Daughter’ (1924) and E.R Eddison’s ‘The Worm Ouroboros,’ (1922), which Tolkien had read and enjoyed, which makes it interesting that the publication of ‘The Lord Of the Rings’ paved the way for Eddison’s books to be reprinted; and my favourite, Hope Mirreless’s ‘Lud-In-The-Mist’ (1926), to name but a few. Lin Carter was an amazing champion to bringing a lot of these classics back to life for Ian and Betty Ballantine. All told about 65 books in the series starting with ‘The Hobbit’ in 1965 through to Lord Dunsany’s ‘Over The Hills and Far Away’ in 1974. A must read is the anthology book edited by Carter titled ‘New Worlds For Old’ which I came across in a second hand bookstore. In fact I knew little about but when another fantasy reader standing beside me at the counter offered me 3 times as much for it before I purchased it I know it was something special. it’s filled with short, obscure stories and poems by some of the greats like Oscar Wilde (“The Sphinx”), H P Lovecraft (“The Meadow”), Lord Dunsany (“The Fall of Babbulkund”), Clark Ashton Smith (“The Hashish Eater”), Edgar Allan Poe (“Silence: a Fable”), Mervyn Peak (“The Party at Lady Cusp-Canine’s”) and much more.

@@@@@ 0, Alan Brown:

The Lord of the Rings is, at its heart, a paean to simpler times, when life was more pastoral. The Shire of the book’s opening is a bucolic paradise; and when it is despoiled by power-hungry aggressors it’s eventually restored by the returning heroes. The elves are portrayed as living in harmony with nature within their forest abodes, and even the dwarves are in harmony with their mountains and caves. In the decades after the book was published, this vision appealed to those who wanted to return to the land, and who were troubled by the drawbacks and complications associated with modern progress and technology. It harkened back to legends and tales of magic and mystery, which stood in stark contrast with the modern world.

I think the word you want is romantic. At its heart romanticism kicked back against the Dark Satanic Mills, where adults and children worked fourteen hour days to make mill-owners rich. Against the ecological devastation growing industrialism produced. Blake and Keats, Byron and the Shelleys, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, the Brownings, shared the values that Tolkien embraced.

That is weird cover art.

Hmm. I’ve heard about first-generation hippies being especially inspired by Snts, who are truly one with an ancient forest and defend it. Were others inspired by the Entwives and hobbits, people of low-tech farming? (Yeah, I know I should be asking my people, not posting here.) I’m a second-generation hippie, so I don’t know what it was likeback then, but the schism of Ents and Entwives — wilderness vs. cultivation — is still a controversy for us, though I think people are increasingly making room for both of them in personal mindset and practice as we challenge the ideological separation od humanity from “nature.”

LotR’s main direct impact on me was mind-swamping adoration of Gollum from 2004 to today. But as the spark for fantasy as I know it, including many a series of wonderfully huge proportions, plus the spark to much of my social life on fantasy-literature (hey Tor, thanks for sharing that Mark Reads link somewhere in your Hobbit/LotR Reread), its indirect impact on my reading has been even bigger.

@@@@@ 20, AeronaGreenjoy:

Hmm. I’ve heard about first-generation hippies being especially inspired by Snts, who are truly one with an ancient forest and defend it. Were others inspired by the Entwives and hobbits, people of low-tech farming? (Yeah, I know I should be asking my people, not posting here.) I’m a second-generation hippie, so I don’t know what it was likeback then, but the schism of Ents and Entwives — wilderness vs. cultivation — is still a controversy for us, though I think people are increasingly making room for both of them in personal mindset and practice as we challenge the ideological separation od humanity from “nature.”

Well, I came upon a child of God

He was walking along the road

And I asked him, Tell me, where are you going

This he told me

Said, I’m going down to Yasgur’s Farm

Gonna join in a rock and roll band

Got to get back to the land and set my soul free

We are stardust, we are golden

We are billion year old carbon

And we got to get ourselves back to the garden

Many hippies did set up rural communes to lead simple, natural lives. The first thing they had to learn was engine maintenance and repair. Tractors, harrows, chain saws, windmills, on and on. They also learned what hard work farming is. Plus the fact that a disorganized, let someone else take care of the hard work, approach lead to hunger and financial disaster. Few of them lasted long. Getting back to the land and setting your soul free = endless stoop labor.

This wasn’t a new idea. Remember the Romantics? A gaggle of them—including Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Robert Southey—planned to settle in frontier America. Live a quiet, simple life. Work two or three hours a day. Spend the rest of their time thinking and writing and communing with nature. Fortunately for the Commonwealth of Letters, the project collapsed before it started.

The Lord of the Rings was a minor contributing factor. The cultural complex that produced the counterculture was far more complex than that.

Thank you for this.

I discovered Tolkien in the 1960’s and the Ballantine paperbacks were the ones I read and they had those covers. In fact, the first book that caught my eye was the one with the snakey guys and the exploding volcano because that was neat (even though it resulted in my reading things in backwards order!). I also remember in the 70’s where every college town had a vegetarian restaurant called something like “The Hobbit Hole” and there were music groups like Thorin and the Oakenshields.

Off topic I listen to people comment that the Silmarillion (or certain specific chapters) are “boring.” When it came out in the late 70’s this was the first new Tolkien we ever saw. We had these little hints about Gondolin, and Turin, and “Orome the Great, in the Battle of the Valar when the world was young” but we had no idea what any of that meant and we just went crazy comparing the new material to what we had speculated these things meant. We didn’t care that there were paragraphs about who was living were. NEW TOLKIEN!!!!!

And then there’s another wonderfully illuminating award winning view of the human condition inspired by LoTR which has remained continuously in print since the late 1960’s. I speak, of course, of “Bored of the Rings”, which Tor really should review someday. It’s a pity.

@22: Oh, I know this counterculture is deeply rooted in many wellsprings. I guess I really meant that I wonder if there were those who explicitly identified with hobbita and Entwives more than Ents and Elves — an obvious yes, I guees, given our contributions to the organic movement — and if the friction between the two schools of thought mirrored the Ent vs. Entwife disagreement. A late-night question, and not really on-topic for this post.

Re: Bored of the Rings, Leah Schnelbach has written about it here: “Hitting the Road with Bored of the Rings“

I haven’t seen that cover art in a long, long time. It was the cover art on the first tLotRs novels I read in the late seventies/early eighties. Pretty trippy.

The funny thing about Tolkien’s works is that many people tend to “claim” it as supporting their particular philosophy or outlook. I’ve seen everything from near Neo-facsits to environmentalists (with somewhat more justification, imho) try to claim it. I would not say that it is particularly “anti-war” as such, indeed, one could argue that it makes the point that some wars are worth fighting (though that is more difficult to apply to the Vietnam War raging as it burst into cultural popularity).

And yes, that was indeed very shameful of Ace Books, basically pirating the work for profit, despite whatever ‘legal’ grounds they had.

You are welcome to disagree with the opinions expressed in the article or in the comments, but please keep the tone of the discussion civil and constructive; aggressive or dismissive comments do not help to further the conversation. Please consult our full commenting guidelines here.

@25,

Huh. I completely forgot about that, and I even commented on it. Thanks for the link!

@@@@@ 24, AeronaGreenjoy:

Oh, I know this counterculture is deeply rooted in many wellsprings. I guess I really meant that I wonder if there were those who explicitly identified with hobbita and Entwives more than Ents and Elves — an obvious yes, I guees, given our contributions to the organic movement — and if the friction between the two schools of thought mirrored the Ent vs. Entwife disagreement. A late-night question, and not really on-topic for this post.

Not to my knowledge.

The closest I can come is the unfortunate hippie children named things like Frodo and Goldberry. I never heard of any kid named Treebeard.

A later generation inflicted their children with Ayla and Jondalar. Which brings me to…

There were debates between advocates of agriculture-for-seven-generations vs. the hunter-gatherers who lived the original low-workload-lifestyle. Fifteen hours a week of work, the rest of the time spent in creative leisure.

Both claims were later debunked.

Some pre-industrial agricultural practices wrecked the land.

Many hunter-gatherers hunted species to extinction. Later research documented the high homicide rate among the “innocent” foraging peoples.

There was a lot of projection on both sides of that debate.

@0, Alan: Another detail you did not include, regarding the influence of FotR, TTT, and RotK on publishing (and writing) fantasy—though it’s probably pretty common knowledge—is that Tolkien did not write a trilogy. Tolkien wrote his Hobbit sequel to be one “book,” but his publishers convinced him it must be broken up into three, so that they could afford to publish them AND so that people could afford to buy them. Thus pragmatics “invented” the fantasy trilogy form, which later was extended by some writers into many more volumes.

@30 this seems similar in some ways to how people have romanticized the good ol days when mothers were ‘at home with their kids’ and didn’t work, instead devoting their energies to their children.

Pfft – back then women were definitely working, and sometimes doing hard labor. They weren’t giving their kids undivided attention, that’s for sure. But the distinction between ‘housework’ and ‘office work’ didn’t really exist back then.

I have a friend with ‘Galadriel’ as a middle name.

> I would not say that it is particularly “anti-war” as such, indeed, one could argue that it makes the point that some wars are worth fighting

Tolkien wrote about Bombadil being in part a repudiation of the pacifist impulse. Namely Bombadil is the pacifist, and insufficient to protect the world.

OTOH the books certainly caution against glorifying war, with attitudes like Faramir’s and Frodo’s.

OTOH again Kings Elessar and Eomer fought a lot side by side. Unclear how much of that was “responding to attacks” vs. “expanding our borders proactively”.

@@@@@ 32, Lisamarie:

@@@@@30 this seems similar in some ways to how people have romanticized the good ol days when mothers were ‘at home with their kids’ and didn’t work, instead devoting their energies to their children.

Pfft – back then women were definitely working, and sometimes doing hard labor. They weren’t giving their kids undivided attention, that’s for sure. But the distinction between ‘housework’ and ‘office work’ didn’t really exist back then.

Time was, housewives dedicated one day a week—I mean a full day—to washing clothes. The modern washing machine did more for women than a lot of feminists.

I remember the first machine my mother got. It was a tub on four legs with an agitator in the middle and a spigot at the bottom. It stood beside a double soapstone sink. She loaded clothes into the tub. Ran hot water in from a short hose screwed into the sink’s faucet. Added soap. Ran the agitator for a while. Drained the tub down another hose aimed at the floor drain. Ran more hot water into the tub to rinse the clothes. Agitated again, drained again. Hauled the dripping clothes into the first sink. Ran every garment through a hand operated wringer, into the second sink. (There was a phrase for a woman who got herself into trouble. She caught her tit in the wringer.) Hung all the clothes on clothes lines to dry. Took the dried clothes in and ironed them. Folded them and put them away. This primitive arrangement was still an enormous labor saver.

Of course housewives didn’t work!

Except during the war, when she was Rosie the Riveter. She ran a machine lathe, making airplane parts.

What I mean is that they weren’t sitting around the house crafting with their kids or personally overseeing every step of their emotional development. They were doing work that was just as vital (and sometimes labor intensive) to keeping the household running. And in a pre-industrial society, the type of work men and women did, while maybe in different spheres, wouldn’t have the clear demarcation as ‘work’ and ‘housework’ as we consider it now.

@35 Lisamarie

I am put in mind of : https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/1392191.Gone_Is_Gone

“even Westerns…”

How horrible!…but not to some of us.