Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

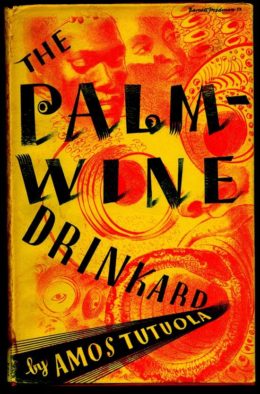

This week, we’re reading Amos Tutuola’s “The Complete Gentlemen,” first published as part of his novel The Palm-Wine Drinkard in 1952. Spoilers ahead. But this story is as much about voice as plot, and our summary can really only do justice to the latter. Go and read!

“I had told you not to follow me before we branched into this endless forest which belongs to only terrible and curious creatures, but when I became a half-bodied incomplete gentleman you wanted to go back, now that cannot be done, you have failed. Even you have never seen anything yet, just follow me.”

Summary

Our narrator calls himself the “Father of gods who can do anything in this world.” Now there’s a name that requires a lot of living up to, but narrator is undeniably a sorcerer of considerable skill, as his story will soon prove!

That story starts with a beautiful man, tall and stout, dressed in the finest clothes—a complete gentleman. He comes one day to the village market, where a lady asks where he lives. But he ignores her and walks on. This lady leaves the articles she’s selling and follows him. She follows him through the market, then out of the village along the road. The complete gentleman keeps telling her not to follow him, but she won’t listen.

They turn off the road into a forest where only terrible creatures dwell. The lady soon wishes to go back to her village, for the complete gentleman begins to return his body parts to the owners from whom he hired them. He pulls off his feet first, which reduces him to crawling. “I told you not to follow me,” he tells the lady. Now that he’s become an incomplete gentleman, she wants to go back, but that ain’t gonna happen.

Indeed not, for this terrible creature returns belly, ribs, chest, et cetera, until he is only a head, neck and arms, hopping along like a bullfrog. Neck and arms go. He’s only a head. But the head has one more rental to return: its skin and flesh, and with those gone, it’s only a SKULL! A Skull that hums in a terrible voice one could hear two miles off, a Skull that chases her when she finally runs for her life, a Skull that can leap a mile in a bound. Running is no good. The lady must submit and follow the Skull to his home.

It’s a hole in the ground, where the Skull ties a cowrie shell around the lady’s neck and instructs her to make a huge frog do for her stool. Another Skull will guard her—the first Skull goes to his backyard to be with his family. If the lady tries to escape, the cowrie will screech an alarm; the guard-Skull will blow his whistle; the Skull’s family will rush in with the sound of a thousand petrol drums pushed along a hard road! What’s more, the lady can’t speak, struck dumb by the cowrie.

The lady’s father begs narrator to find his daughter. Narrator sacrifices a goat to his juju. Next morning he drinks forty kegs of palm-wine. Thus fortified, he goes to the market and looks for the complete gentleman. Soon he spots him, and what? Though knowing what a terrible and curious creature the gentleman really is, narrator understands at once why the lady followed him. He can’t blame her, for the gentleman is indeed so beautiful all men must be jealous, yet no enemy could bear to do him harm.

Buy the Book

Middlegame

Like the lady, narrator follows the complete gentleman from market into forest, but he changes into a lizard so he can follow unseen. He observes the shedding of body parts, arrives at the hole-house in which the ensorceled lady sits on her frog-stool. When the Skull-Gentleman leaves for the backyard and the guard-Skull falls asleep, he turns from lizard to man and tries to help the lady escape. Her cowrie sounds, the awakened guard-Skull whistles, and the entire Skull family rushes into the hole. Skulls try to tie a cowrie on narrator, but he dissolves into air, invisible, until they go away.

His second attempt to free the lady goes better, and they make it to the forest. Again her cowrie betrays them and the whole Skull family gives pursuit, rumbling like stones. Narrator changes the lady into a kitten, tucks her into his pocket, then changes into a sparrow and flies away to the village. All the time the cowrie keeps shrilling.

The lady’s father rejoices to see her and names narrator a true “Father of gods.” But her cowrie continues to shrill, and she remains dumb and unable to eat. Nor can she or anyone else, including narrator, cut the cowrie from her neck. At last he manages to silence the cowrie, but it remains fast.

Her father, though grateful, suggests that the “Father of gods who could do anything in this world” should finish his work. Narrator fears returning to the endless forest, but ventures forth. Eventually he sees the Skull-Gentleman himself, turns into a lizard, and climbs a tree to observe.

The Skull cuts a leaf from one plant and holds it in his right hand saying, “If this leaf is not given to the lady taken from me to eat, she will never talk again.” From another plant he cuts a leaf and holds it in his left hand saying, “If this leaf is not given to this lady to eat, the cowrie on her neck will never be loosened and will make a terrible noise forever.”

The Skull throws both leaves down, presumably to be lost on the forest floor. When he’s gone, narrator collects the leaves and heads for home.

There he cooks the leaves and gives them to the lady. When she eats the first, she at once begins to speak. When she eats the second, the cowrie falls from her neck and disappears. Seeing the wonderful work he’s done, her parents bring narrator fifty kegs of palm-wine, give him the lady for his wife and also two rooms in their house!

And so he saved the lady from the complete gentleman later reduced to a Skull, and this was how he got a wife.

What’s Cyclopean: Tutuola plays freely with English grammar and dialect. One of the more startling, yet delightful, phrases comes when the Gentleman “left the really road” and heads into the mythic forest. A useful description next time your directions include several steps after turning off the paved road.

The Degenerate Dutch: The Palm-Wine Drinkard was lauded internationally, but criticized in Nigeria itself for dialect that many thought more stereotype than reality. (Tutuola’s Wikipedia article includes several rebuttals and favorable comparisons to the linguistic games of Joyce and Twain.)

Mythos Making: Those skulls would fit right in among the Dreamlands bestiary.

Libronomicon: No books this week.

Madness Takes Its Toll: No madness this week, though presumably a certain amount of drunkenness after the palm wine is delivered.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

We do keep delving back into The Weird. The VanderMeers’ editorial chops are on full display here; it’s irresistible in its variety. For a modern weird fiction aficionado, it can be all too easy to draw a clear-seeming line of inheritance back to Lovecraft, Weird Fiction, and its sister pulps. This anthology transforms that linear diagram into something wonderfully non-Euclidean. Some strands represent obscure lines of influence; others like “The Town of Cats” show how the same fears and obsessions play out in parallel across narrative traditions.

Tutuola seems to fit more in the latter category. He draws on Yoruba folklore and weaves it into modern (50s) Nigerian experience—though many of these strands have since been woven into American horror and weird fiction. Thanks to Neil Gaiman’s riffs on Anansi’s stories, I can recognize some of the archetypes behind “the father of gods who could do anything in the world,” desperate to retrieve his palm-wine tapster—desperate enough, in fact, to perform a few miracles. Hello, trickster.

Then there’s the body horror, familiar simply from common humanity. I doubt there’s a culture out there where people wouldn’t draw a little closer to the campfire (real or pixelated) at the image of the Complete Gentleman gradually returning body parts until he’s back to his fully-paid-off skull-self. It reminded me—this time going back to a different writer of horror comics—of a particularly apocalyptic section of Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing run, wherein a woman betrays her friends to a cult in order to learn how to fly. This turns out to involve the transformation of her severed head into a really disturbing bird, giving me a set of delightfully vivid images to go along with the transformation of Gentleman into flying skull.

But there’s more here than just body horror. The Gentleman’s body parts are rented. From “terrible and curious creatures.” Are these parts of their bodies, rented out by the day to make ends meat (sorry not sorry)? Do they keep their own cowrie-captive humans, and rent out their body parts? Either way is more disturbing than just a skull passing as a beautiful man. Not only those who must pay for temporary use of the parts, but those who rent them out, lose something that seems fundamental. And yet, most of us rent out our hands, feet, even brains by the hour or by the year, and lose some use of them thereby. And through that rental gain what we need to keep flesh and blood together in the literal sense; we encompass both sides of the skull’s transaction. Disturbing, when you think about it too clearly, which Tutuola seems inclined to make you do.

Whatever their origin, these are impressive body parts, adding up as they do to such great beauty. The kind that draws women to follow, and men (and Fathers of Gods) to jealous admiration, and terrorists (and bombs, per our narrator) to mercy. As in “Dust Enforcer,” the mixture of mythic and modern violence is potent and alarming.

Lots to think about from a seemingly simple tale—and an intriguing taste of Tutuola’s storytelling.

Anne’s Commentary

In his NYT Book Review essay “I Read Morning, Night and in Between: How One Novelist Came to Love Books,” Chigozie Obioma describes his father telling him fantastic stories when he was sick in hospital. He believed his father made up these stories, until the day his father responded to his plea for more by handing him a well-worn book. Here, Chigozie was eight and could read for himself; let the book tell him stories. The first Chigozie tried was one he remembered his father telling, about a complete gentleman, really a skull, and the lady who followed him into an endless forest. So his father hadn’t invented the story himself! He’d gotten it from The Palm-Wine Drinkard by Amos Tutuola, and the reason his father had told the story in English, not the Igbo in which Chigozie’s mother told her folk tales, was because Tutuola had written it in English, not his own birth language Yoruba.

Obioma summarizes his epiphany thus: “While my mother, who had less education than my father, relied on tales told to her as a child, my father had gathered his stories from books. This was also why he told the stories in English. It struck me that if I could read well, I could be like my father. I, too, could become a repository of stories and live in their beautiful worlds, away from the dust and ululations of Akure.” And he did indeed become a voracious reader. Who can argue with that? Not Amos Tutuola, though I do think he’d take issue with Obioma’s seeming devaluation of folk tales straight from the folk.

Another NYT article dated February 23, 1986 features an interview of Tutuola by Edward A. Gargan. Tutuola talks about how his child-imagination was sparked and fueled: “During those days in the village, people had rest of mind… After they returned from the farm, after dinner people would sit in front of houses. As amusement people told folk tales—how people of days gone by lived, how the spirits of people lived. So we learned them…There are thousands of folk tales. The ones I like the most, well, I prefer frightening folk tales.”

Those would be the ones where people venture from the village into the bush, and “bush,” as Gargan notes, “is that place between villages, between destinations, an expanse of unknown, whether jungle or plain, that must be traversed…[the place] where his characters confront life, their own doubts and fears, their destiny.” People plunging into the unknown, the inexplicable, the endless forest of things which defy naming or should not (for the sake of human sanity) be, that ties Tutuola’s fictive world to Lovecraft’s. What divides their worlds is the resilience of Tutuola’s protagonists, here the sorcerer or jujuman whose elite shapeshifting skills conquer even a terrible clan of Skulls. And not only does he keep his sanity, he gets a wife out of it, plus fifty kegs of palm-wine and an in-law apartment! Could be the happiest ending we’ve encountered so far. At least it’s in competition with Benson’s “How Fear Departed From the Long Gallery.”

I’m not linguistically or culturally equipped to leap into the fray over Tutuola’s unique marriage of English with Yoruba syntax, speech patterns and storytelling traditions. The Palm-Wine Drinkard was immediately admired by many British and American critics, while many Nigerian critics waxed severe. The book could do nothing but feed the West’s view of Africans as illiterate, ignorant and superstitious. The balance has swung back in the direction of praise. For my part, I enjoyed listening to a praise-singer singing his own praises as loudly and confidently as any of Mark Twain’s tall-tale spinners.

However, I’m willing to grant the Father of Gods my suspension of disbelief if only for the pleasure of filling in the spaces on the fictive canvas he leaves for me. For instance, if “only all the terrible creatures were living” in the endless forest, then I take it no humans live there. In which case, who are these helpful renters who supply the Skull-Gentlemen with his human accessories? And where do they get their stock? Terrible creatures indeed! I wouldn’t want to rent a foot and not return it on time. Imagine the late penalties. I am, while counting my feet.

The horror-show of the gentleman shedding his parts? One could imagine that as anything from the Burtonesque drollery of Sally or the Corpse Bride bloodlessly dropping an arm to something more Walking Dead gory or Alien oozy. And the bullfrog the lady’s forced to sit on! You could picture it as a taxidermied toad-stool, but I prefer it alive and lively. Since the Skulls live in a hole, and since it’s obviously not a hobbit hole, I see it as full of worm ends, and ants, and beetles, and grubs, and centipedes, and who knows what crawly creepers. Our lady’s lucky she has that giant frog poised to flick out its tongue and wetly SMACK each creeper off her shrinking skin before the fact her cowrie keeps her from screaming drives her mad.

Come to think, the Skull family should market those bullfrog stools.

We’re off for the holidays! When we return, a tale of the horrors of whaling (some expected and others… less so) in Nibedita Sen’s “Leviathan Sings to Me in the Deep.”

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. She has several stories, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, available on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.