Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

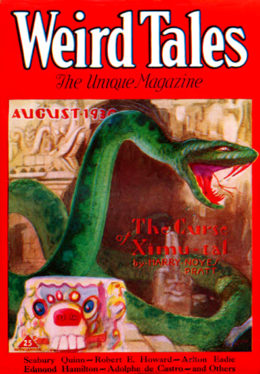

Today we’re looking at “The Electric Executioner,” a collaboration between Lovecraft and Adolphe de Castro first published in the August 1930 issue of Weird Tales. Spoilers ahead.

“You are fortunate, sir. I shall use you first of all. You shall go into history as the first fruits of a remarkable invention. Vast sociological consequences—I shall let my light shine, as it were. I’m radiating all the time, but nobody knows it. Now you shall know.”

Summary

Unnamed narrator thinks back forty years to 1889, when he worked as auditor and investigator for the Tlaxcala Mining Company. The assistant superintendent of its mine in Mexico’s San Mateo Mountains has disappeared with the financial records. Narrator’s job is to recover the documents. He doesn’t know the thief, Arthur Feldon, and has only “indifferent” photos to go by. Tracking Feldon won’t be easy, for he may be hiding in the wilderness or heading for the coast or lurking in the byways of Mexico City. No balm to narrator’s anxiety, his own wedding is just nine days off.

He journeys by agonizingly slow train toward Mexico City. Nearly there, he must abandon his private car for a night express with European-style compartment carriages. He’s glad to see his compartment’s empty and hopes to get some sleep. Something rouses him from his nodding—he’s not alone after all. The dim light reveals a rough-clad giant of a man slumped sleeping on the opposite seat, clutching a huge valise. The man starts awake to reveal a handsome bearded face, “clearly Anglo-Saxon.” His manners aren’t as prepossessing, for he stares fiercely and makes no response to narrator’s civilities.

Narrator settles himself to sleep again, but is roused by some “external force” or intuition. The stranger’s glaring at him with a mixture of “fear, triumph and fanaticism.” The “fury of madness” is in his eyes, and narrator realizes his own very real danger. His attempt to draw a revolver inconspicuously is for naught—the stranger leaps at him and wrests the weapon away. The stranger’s strength matches his size. Without his revolver, the “rather frail” narrator is helpless, and the stranger knows it. His fury subsides to “pitying scorn and ghoulish calculation.”

Stranger opens his valise and extracts a device of woven wire, something like a baseball catcher’s mask, something like a diver’s helmet. A cord trails into the valise. Stranger fondles the helmet and speaks to narrator in a surprisingly soft and cultivated voice. Narrator, he says, will be the first human subject to try his invention. You see, stranger has determined that mankind must be eradicated before Quetzalcoatl and Huitzilopotchli can return. Repulsed by crude methods of slaughter, he’s created this electric executioner. It’s far superior to the chair New York State has adopted, spurning his expertise. He’s a technologist and engineer and soldier of fortune, formerly of Maximilian’s army, now an admirer of the real and worthy Mexicans, not the Spanish but all the descendents of the Aztecs.

Narrator knows that once they reach Mexico City, help will be at hand. Until then, he must stall the madman. He starts by begging to write a will, which stranger allows. He then persuades stranger he has influential friends in California who might adopt the electric executioner as the state’s form of capital punishment. Stranger lets him write them a letter, complete with diagrams of the device. Oh, and won’t stranger put the helmet on, so he can get an additional sketch of how it fits the condemned man’s head?

Stranger agrees, for surely the press will want the picture. But hurry!

Having delayed as long as possible with the above ruses, narrator switches tactics. He musters his knowledge of Nahuan-Aztec mythology and pretends to be possessed by its gods. Stranger falls for it. Among other tongue-twisting deities, he invokes “Cthulhutl.” Narrator recognizes this name as one he’s encountered only among the “hill peons and Indians.”

Luckily he remembers one of their whispered invocations and shouts: “Ya-R’lyeh! Ya-R’lyeh! Cthulhutl fhtaghn! Niguratl-Yig! Yog-Sototl—”

Stranger falls to his knees in religious ecstasy, bowing and swaying, muttering “kill, kill, kill” through foam-flecked lips. Luckily again, for narrator, stranger’s still wearing the wire helmet when his paroxysms pull the rest of the electric executioner to the floor and set it off. Narrator sees “a blinding blue auroral coruscation, hears a hideous ululating shriek, smells burning flesh.

The horror’s too great. He faints. An indeterminate time later, the train guard brings him around. What’s wrong? Why, can’t the man see what’s on the floor?

Except there’s nothing on the floor. No electric executioner, no enormous corpse.

Was it all a dream? Was narrator mad? Nah. When he finally gets to his mining camp destination, the superintendent tells him Feldon’s been found in a cave beneath the corpse-contoured Sierra de Malinche. Found dead, his charred-black head in a weird wire helmet attached to a weirder device.

Narrator steels himself to examine Feldon’s corpse. In Feldon’s pockets he finds his own revolver, along with the will and letter narrator wrote on the train! Did insane genius Feldon learn enough Aztec “witch-lore” to astrally project himself to his pursuer’s compartment? What would have happened if narrator hadn’t tricked him into putting on the helmet himself?

Narrator confesses he doesn’t know, nor does he want to. Nor can he even now hear about electric executions without shuddering.

What’s Cyclopean: Adding tl to all your made-up words totally makes them sound Aztec.

The Degenerate Dutch: In spite of casual references to “thieving native” Mexicans, and Feldon being “disgustingly familiar” with them, rather a point is made of Feldon’s own Anglo-ness. He has his own opinions of “Greasers” (hate ‘em) and “full-blood Indians” (inviolate unless you’re planning to remove hearts on pyramid-top). Oh, but wait, he’s joined the cult of Quetzalcoatl and the Elder Gods (new band name?) so he’s an honorary scary brown person.

Mythos Making: The gentleman with the valise prays to the Aztec deities (and, occasionally and confusedly, the Greek) in precisely the words and tones ordinarily used by your everyday Cthulhu cultist. And then, of course, we get to “Cthulutl” himself, along with “Niguratl-Yig” and “Yog-Sototl.” Who are worshipped in secret by brown people, and totally unrecorded by academics except for every single professor at Miskatonic.

Libronomicon: The obsession of native Mexicans with Cthulhutl never appears in any printed account of their mythology. Except, probably, for the Intro Folklore texts at Miskatonic.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Feldon’s a “homocidal maniac,” unless he’s just taking orders from R’lyeh. Narrator recognizes this instinctively in spite of not yet being graced by Freud’s insights. In fact, Feldon appears to be not merely mad, but a mad scientist. Unless he’s a figment of the narrator’s own madness… which is probably not the way to bet.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

“I realised, as no one else has yet realised, how imperative it is to remove everybody from the earth before Quetzalcoatl comes back…” Well, that’s not alarming or anything.

Is it time to talk about mental illness in Lovecraft again? It might be! Lovecraft is famously obsessed with madness, to the point where people who haven’t even read him will still get your jokes about sanity points. He’s not exactly nuanced on the matter, but “The Electric Executioner” points up a couple of places where he usually does better than, say, your average slasher film.

Specifically, Feldon the “homocidal maniac” makes me realize that as in real life, if rarely in horror, Lovecraft’s madmen are much more likely to be victims than attackers. His cultists may rant; his narrators generally fear not madmen but their own decent into madness. Or stranger and more interesting, they hope that they’ve already so descended, in preference to accepting the truth of their perceptions. “Executioner’s” narrator does a bit of this, but Feldon’s an outlier. One suspect’s it’s de Castro, then, who emphasizes how Feldon’s madness makes him dangerous—for example, by making him indifferent to the threat of a gun. Lovecraft’s maddened narrators are rarely indifferent to danger—rather the reverse. The mad scientist* just isn’t his style.

Also likely due to de Castro’s involvement: Narrator has relationships! With girls! And serious motivation outside the occult! Indeed, the whole plot is shockingly (so to speak) carried along by ordinary Earth logic. Not for this week’s narrator the unbearable tension between curiosity and fear, attraction and repulsion. He’s been hired to do a job; he wants to get to the church on time; he’s frustrated by the vagaries of the Mexican railroad. It’s rather refreshing.

Feldon is painted with a broader brush—but under the broad strokes of his show-them-show-them-all mad cackling, an intriguing one. Before he was an unappreciated inventor, he was a soldier in Maximillian’s army. That would be his majesty Maximillian the 1st, an Austrian naval officer handed an ostensible Mexican empire by Napoleon III of France. What could Lovecraft approve of more? Feldon was a true defender of the Anglo (or at least European) culture that’s all that stands between civilization and the One True Religion. So for him of all people to “defect” to the dark side, worshipping Cthulhutl and shouting “Ïa!” alongside the “peons,” makes him that much more villainous.

Have I mentioned lately that when a religion is favored by oppressed people everywhere, I tend to have some sympathy towards it? Even if some of Cthulhu’s (Cthulhutl’s) worshippers go a little overboard—well, what religion hasn’t been used as an occasional excuse for bloodshed and attempts to immanentize the eschaton?

Feldon doesn’t honestly seem like a particularly good Cthulhu cultist, either. Even taking the nastiest claims seriously, isn’t destroying humans supposed to be His Tentacled Dreadfulness’s job, after He wakes up? And trying to get them out of the way one by one, artisanal executions that require exact adjustment of electrical components, doesn’t seem very efficient. Perhaps Feldon thinks it’ll be a while before the Big Guy wakes up. All the time in the world…

Of course, in proper mad scientist tradition, he’s ultimately destroyed by his own invention. Which, as long as you’re a solipsist, has the same basic effect and is much more efficient. So maybe it was a reasonable plan after all. For certain definitions of reasonable.

*The sad truth is that most mad scientists are really just mad engineers.

Anne’s Commentary

I read “The Electric Executioner” on the Amtrak train from Washington to Providence, having backed Ruthanna on the Lovecraft panel at the Association of Writers and Writing Programs conference. I was heartened to see how many students and teachers of literary fiction and poetry were interested in Howard—secret geeks lurk in the hallowed halls of the most prestigious academic institutions of our land! Some are even bold enough to wear Cthulhu Rising T-shirts, right out in the open! Stars align. Ruthanna wore a cryptic gold brooch that might represent Dagon or Hydra or some still more potent sea-deity. I wore my tri-lobed burning amulet. A speaker on another panel looked very much like Lovecraft reconstituted by Joseph Curwen. There were, indeed, many portents of the Great Old Ones and Their imminent return…. [RE: Speaking of which, welcome to the new readers who asked about the blog series after our panel. Pull up a cyclopean seat!]

But back to the train. I saw lots of huge valises and one enormous bass violin that had to occupy its own seat because nowhere else to stow it. It was the night train, too, but no one bothered me. Maybe because I sat in the Quiet Car, where executions of all kinds are forbidden, as they tend to get noisy. It was nevertheless an atmospheric setting in which to read this week’s story. Alas, the bass violin as wobbled up and down the aisle by its diminutive owner was scarier than the tale.

Polish-born Adolphe Danziger (Dancygier) de Castro appears to have been a colorful scamp. He claimed to have received rabbinical ordination, as well as a degree in oriental philology. After emigrating to the United States, he worked as a journalist, a teacher, a dentist. He was a vice-consul in Madrid and an attorney in Aberdeen and California. He spent some time in Mexico in the twenties, finally settled in Los Angeles in the thirties. He married a second wife without divorcing the first and lived to nearly one hundred, having written essays, novels, short stories, poems, a film script and a biography of Ambrose Bierce. Lovecraft revised two of his earlier efforts, today’s story and “The Last Test.” He corresponded with de Castro from 1927 to 1936, and yet he described “Old Dolph” in rather snarky terms:

“[He’s] a portly, sentimental, & gesticulating person given to egotistical rambling about old times & the great men he has intimately known. … he entertained everybody with his loquacious egotism & pompous reminiscences of intimacies with the great. … regaled us with tedious anecdotes of how he secured the election of Roosevelt, Taft, & Harding as Presidents. According to himself, he is apparently America’s foremost power behind the throne!”

Could be Howard was in a bad mood when he penned that less-than-shining portrait of a friend, but he doesn’t seem to have expended much effort on de Castro’s “Executioner.” I find it one of the weaker revisions. That interminable opening travelogue, in which our narrator complains about every delay! It took me about an hour to get through that, as my own train’s gentle swaying kept rocking me to semi-sleep, from which only the ominous hollow reverberations of my bass violin neighbor could rouse me. That preposterous appearance of Fenton, who ought to have been hard to overlook even in dim light! And what’s with this frail guy auditing and investigating the toughs of mining camps? That wasn’t the picture I’d formed of him before it became plot-convenient to make him so much weaker than the (equally oddly) ginormous Fenton. I could have bought that Fenton had been on to narrator’s pursuit and was stalking him in person, meaning to both kill off an antagonist and secure a “worthy” test subject in one fell swoop. But some kind of late-mentioned astral projection? Nope.

I’m not even going to get into the Brer Rabbit, delay-the-stupidly-egotistical-villain trope, except to say that Fenton disgracefully falls for the obvious ploy, not once but thrice. Plus he monologues big-time. Sounding a bit like de Castro per Lovecraft’s snark, come to think.

The “Aztecization” of Mythos deities (Cthulhutl, Yog-Sototl) was amusing but far too little developed to seem anything but tacked on at the last minute. Too bad Lovecraft didn’t write his own story about the secret and ancient rituals practiced in Mexico’s remote mountains.

So, not a favorite. I am intrigued by the conceit of a corpse-shaped mountain range, though. That would be very cool viewed in black silhouette against a Meso-American inferno of a sunset.

Next week, explore the legends of exotic Tennessee in Gene Wolfe’s “Lord of the Land.” You can find it in Cthulhu 2000, among others.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint on April 4, 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.